Who is voting for the PPC — and will they cost the Conservatives a win?

The People's Party is on the rise, but it's unclear what its impact will be

As we enter these last days of the campaign, the polls are looking a lot like they did back in 2019: the Liberals and Conservatives are neck-and-neck, the NDP is well back but an important factor, and the Bloc may or may not be a big spoiler on election night.

So, like in 2019, I’m sure there will be some surprises.

But the thing I’m most unsure about is the People’s Party.

The big differences on where the polls put the PPC have gotten smaller in recent days, but there is still a sizable discrepancy between polling firms. The polls published on Monday put the party between 4% and 8% — a wide variation for a party with single-digit support. By comparison, the Greens registered just 3% or 4% in the same surveys.

This is a narrower band than what we were seeing last week, when the range was as wide as 2% to 12%. But the PPC nevertheless remains a big question mark. Will they go off like a rocket or a damp squib on election night?

The way that pollsters collect their data seems to be one of the contributing factors in these discrepancies. It’s the IVR polling firms (EKOS, Mainstreet and Forum) that have had the PPC in the high single-digits or north of 10%. It’s the online polling firms (Léger, Ipsos, Abacus, the Angus Reid Institute and others) that have had them at 5% or lower.

Nanos, which does its polling with live-callers over the telephone, has ranged somewhere in the middle, putting the party at around 5% to 7% in recent days.

What could be behind this? On last week’s episode of The Writ, David Coletto of Abacus Data laid out some theories, first on why the online polls might have trouble picking up PPC voters:

"One [theory] is: are people who are inclined to vote for the People’s Party going to sign up for online panels … It makes sense to me that they would be less likely to take part because they seem like anti-system-type voters who don’t want to be part of giving their views on, not just politics, but consumer products and other things like that.”

Coletto also explained why the automated IVR polls might be more successful at finding Maxime Bernier’s supporters:

“On the other hand, particularly the IVR polls are much more a victim of response bias meaning, dependent on the mood of certain groups in the electorate, if they are angry, if they are agitated, if they are excited, are they more likely to actually not only pick up the phone but, when they find out it is a survey about politics, complete it.”

In the end, Coletto concludes that both factors might be at play, meaning the truth of the matter is somewhere in between.

It’s hard to know for certain, however, because the PPC’s voter coalition is a new one.

Pollsters had no issues with the PPC vote last time. The party captured just 1.6%, but the discrepancies between pollsters was minimal. Telephone, IVR and online polls all had the PPC between 2% and 3%, though the online polls were more often on the lower end with the IVR polls at the higher end of that tiny range. The PPC didn’t match its polls, but there was no real uncertainty about the party’s strength (or lack of it) in the last election.

The PPC voter universe

But voters’ motivations in 2019 were different.

Back then, Bernier’s top issues were things like immigration, supply management and fiscal responsibility. He wasn’t talking about lockdowns and vaccination. No one was.

They are now. But who are they?

Digging through the crosstabs of recent polls by different pollsters, a picture of the PPC voter does emerge. This voter is more likely to be a man than a woman. He is under the age of 50 and is more likely to have a high school or college education than a university degree, but he isn’t poor. If you had to type-cast a PPC voter, he’d probably be a man in his 30s working in the trades.

He’d also share a lot of views with the Trump-loving base of the U.S. Republican Party.

A Forum Research poll found that a majority of PPC supporters are:

unvaccinated;

opposed to vaccine mandates;

opposed to gun control;

approving of Donald Trump;

doubtful or unsure of humans’ role in climate change.

A majority of every other party’s supporters felt the opposite way. That’s because few Canadians see the world like PPC voters do. But the PPC is all alone on that part of the spectrum.

PPC strongest in Alberta and Prairies

They are spread out across the country pretty evenly, which is a bad thing in a first-past-the-post electoral system. It will be hard for the PPC to concentrate enough votes anywhere to win a seat.

According to the Poll Tracker, the PPC is strongest in Alberta with 9% support, followed by 8% in the Prairies (a little higher in Saskatchewan, a little lower in Manitoba), 7% in Ontario, 6% in British Columbia, 6% in Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick is marginally the PPC’s best Atlantic province, Nova Scotia its worst) and 4% in Quebec.

Looking at the sub-regional breakdowns in some recent polls by Counsel Public Affairs and Léger, the PPC appears strongest in rural Alberta (10%), southwestern Ontario (8%), the Quebec City area (7%, presumably including Bernier’s Beauce riding) and the Hamilton-Niagara region (7%).

The Poll Tracker has similar estimates, with the PPC topping double-digits only in rural Alberta (12%) and southern Saskatchewan (10%). Indeed, there are 15 ridings in these regions were the PPC is projected to finish with more than 10% of the vote. There are another four in southwestern Ontario.

But will these votes make a difference if the PPC remains seatless?

Where the PPC-Conservative vote split matters

Let’s start with the simple (and simplistic) premise that a vote for the PPC is a vote that would have otherwise gone to the Conservatives.

There are 28 ridings across the country where the Poll Tracker estimates the PPC’s share of the vote will be greater than the margin between the Conservatives and the party projected to win the seat. The Liberals are favoured in 22 of these seats, the NDP in five and the Bloc in one.

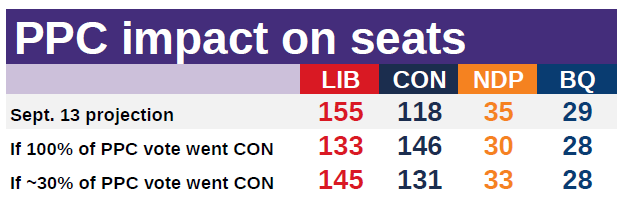

Using Monday’s projection, if those 28 ridings were instead given to the Conservatives the party would end up with 146 seats to just 133 for the Liberals, 30 for the NDP and 28 for the Bloc. That kind of seat advantage would probably mean a Prime Minister Erin O’Toole.

But, of course, every PPC vote is not a vote that would otherwise have gone to the Conservatives.

According to data provided by Abacus from their surveys conducted from September 9 to 12, about 60% of PPC supporters voted for the Conservatives or PPC in the last election, roughly split down the middle. Another one-fifth did not vote in 2019 — either because they were too young or just didn’t turn out — while the rest voted for the Liberals (about half of the remainder), the NDP, Greens or Bloc Québécois.

Yes, the PPC’s gains have come primarily from the Conservatives but, combined, they’ve gained more from new voters and all the other parties.

If we instead award the PPC the votes they’ve gained from the Conservatives, the number of ridings in which the PPC is splitting the vote to elect Liberal, NDP or Bloc candidates is just 13. If those seats are awarded to the Conservatives, they’d wind up with 131 and back on the opposition benches. The Liberals would still win 145, the NDP 33 and the Bloc 28.

Certainly, these PPC votes could matter a lot in some individual ridings.

Notable among them are seats like Peterborough–Kawartha and Kitchener South–Hespeler in Ontario, Edmonton Griesbach in Alberta, and Miramichi–Grand Lake in New Brunswick. That last one was incredibly close last time and, to make matters more intriguing, the People’s Alliance of New Brunswick — a far tamer populist outfit that nevertheless drapes itself in purple — holds a provincial riding in the region.

I have no doubt that, when the votes are counted, we’ll be able to identify some ridings where the rising PPC cost the Conservatives a win.

But I think the Conservatives’ biggest problem is the inefficiency of their vote, not what they have lost to the PPC, most of which is in ridings where the Conservatives routinely win by gargantuan margins. At the moment, the race for seats doesn’t look close enough for the PPC to make the difference between re-election or defeat for Justin Trudeau.

I've actually been wondering what Maxime Bernier's game is. As an exercise in political strategy, very little about what the PPC is doing makes a lick of sense.

The way you break through in modern Canadian politics is that you find a unique local political ecosystem which isn't being serviced by any of the major parties, and you plant your flag in it. By taking this local approach, you're giving yourself a built-in wedge against the national parties, who generally can't cater in quite the same way. Having established yourself as a regional power, you can then attempt to nationalize if you so desire, but you have to crack the nut first.

Thus, the Reform Party was able to break through in part because, having no real ambition of winning any seats east of Winnipeg, they were able to adopt positions on issues like official bilingualism and the constitution which would have been radioactive to any party that aspired to do well in Quebec or Atlantic Canada. (Then, once Preston Manning was ensconced in Stornoway, he gradually decided that maybe he'd been too doctrinaire on these issues...) Cater to that local ecosystem to break through, then nationalize once you're legitimate.

The PPC is doing the opposite of this, running an expensive national campaign on the apparent assumption that they're going to win 8 seats in diverse parts of the country, all at once. (Beauce, Fort Mac, southwestern Ontario, suburban Toronto...) And they're choosing to do this by focusing on a constituency (the stridently unvaccinated) which will only ever get them to about 10% of the vote at most, spread so thinly across the country that it won't win them any seats. This community will be reliable supporters, but in no part of the country will they come close to forming a plurality of the electorate.

I can only make sense of this approach if THAT's the goal: if this is less a serious effort to win seats, and more about achieving sustained national relevance outside the conventional political system. Is Maxime Bernier running for parliament, or is he running for a recurring gig in the North American conservative media ecosystem?

I would note that one of these jobs probably pays better than the other: there are a lot of conservative commentators who make a lot more money than you do as an Independent MP, and the work's probably a lot less stressful, to boot...

As the centre becomes overcrowded, especially with O'Toole tacking left, the PPC appears to be the party of the disgruntled, gathered around an anti-anything that hurts me right now animus. Given the pandemic and lockdowns, there's plenty of unhappiness to go around.

Bernier's open-ended, less government, conservative individualism becomes a sufficiently ill-defined flag to wave for meme-addicts to burnish and dance around. The fact some of them have settled on blocking hospital entrances seems a pretty clear indication some of them are not very serious thinkers. More like serious drinkers. Folks who stay too long at the party, get too drunk, can't find the keys to the car. Find themselves politically homeless.

It's unclear Bernier can shape them into anything politically significant. He could just as easily have named it The Other Party. The one everyone leaves when the booze runs out. The booze, in this case, being pandemic disruption.

As for Bernier's game. He wanted to be leader of the CPC. He lost. Now he's stomping about in a huff trying to gather a crowd!

I love this video of Bernier rallying a few fellow revolutionaries. It's a lazy day in cottage country, folks are catching a little shade, a few rousing words from the revolutionary leader who couldn't even muster a few pitchers of lemonade for the sun-soaked troops, who are so roused to charge the barricades that they...politely clap. Compare them to the folks throwing rocks at Trudeau and blocking hospitals. https://twitter.com/ClintonDesveaux/status/1428749242311581697

Can Bernier pull all this together into something with coherent and effective political clout? Seems unlikely unless something unexpected happens. And Bernier rips off his shirt revealing he's Superman and Jesus rolled into The One! Oh right, Trump already starred in that movie.🙃