Weekly Writ 2/5: Conservatives and Liberals set fundraising records in 2025

Conservatives outraised the Liberals again, but the post-election gap has gotten smaller.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Thursday morning.

Despite losing the election in April and trailing in the polls throughout most of the year, the Conservatives nevertheless continued to be a fundraising behemoth in 2025.

But, since the election, the Liberals have closed the gap.

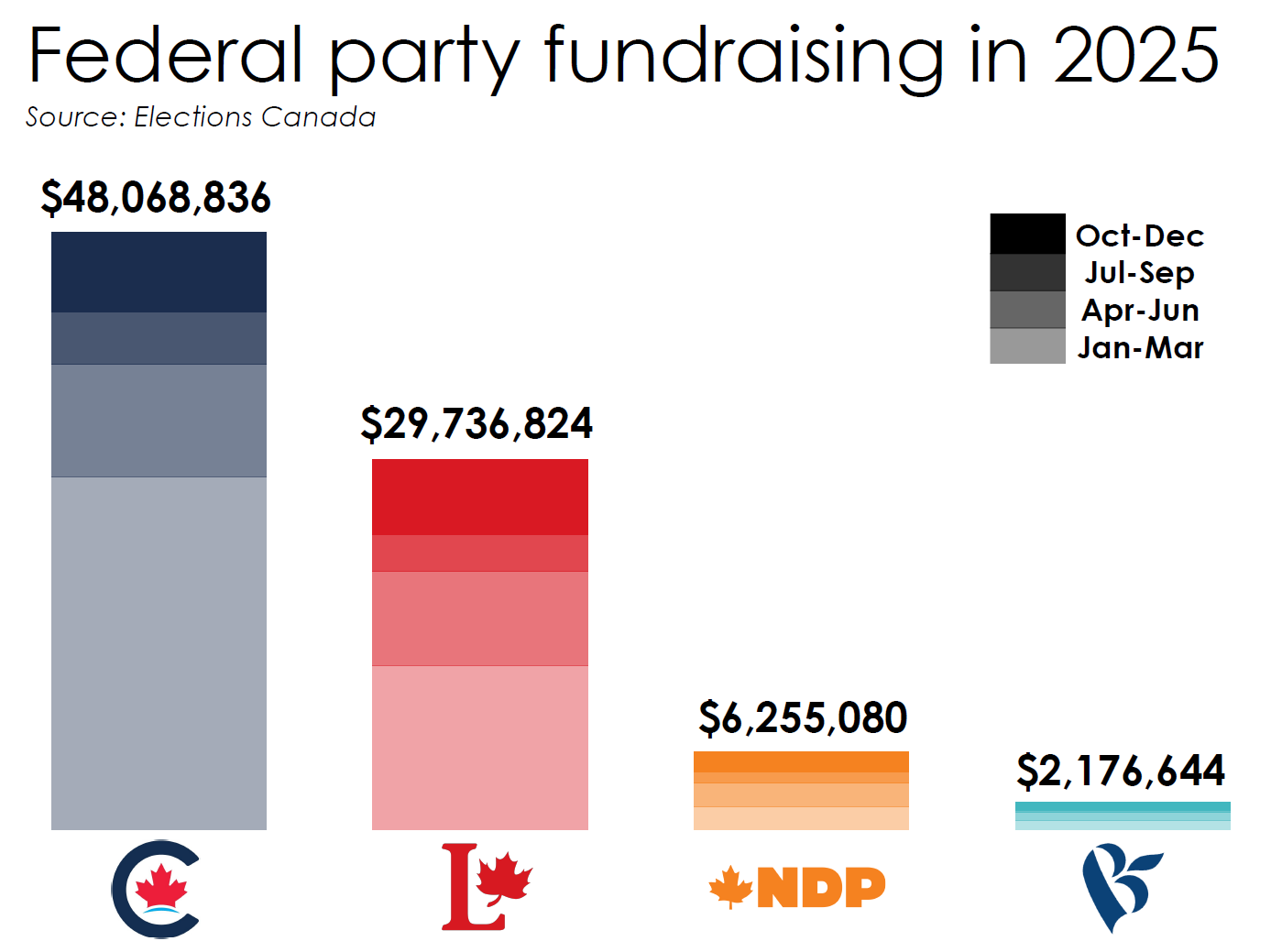

Fundraising data published by Elections Canada last week shows just how much money the four major parties raised in 2025. (The Greens and People’s Party, because they failed to obtain at least 2% of the vote, are no longer required to file quarterly.) The Conservatives led the way, raising the most money for the 16th consecutive quarter and 21st consecutive year, going back to when the fundraising rules and reporting requirements changed in 2005.

The Conservatives raised $6,415,000 in the last quarter of the year from 42,000 individual contributions. This was their lowest Q4 since 2021 which, not coincidentally, was also the last Q4 in an election year. For the year as a whole, the Conservatives raised $48.1 million. That is a record high for the party, which beats their previous record of $41.7 million set in 2024.

The Liberals raised $5,995,000 in the fourth quarter from 41,000 contributions. That is the party’s best Q4 since 2020. With $29.7 million raised throughout the year, the Liberals set a new record. Their previous high had been $21.7 million in 2015.

The gap between the Liberals and the Conservatives has shrunk over the last three quarters. Over that time, the Conservatives raised only $3.1 million more than the Liberals. By comparison, the Conservatives were out-fundraising the Liberals in the last three quarters of 2023 by $15 million and of 2024 by $18.9 million.

The New Democrats raised $1,640,000 from 14,500 contributions in the fourth quarter. That brings their annual haul to just $6.3 million, roughly on par with where the party has been for the last four years.

While the NDP’s Q4 performance represents its worst fourth quarter since 2011, the contestants for the party’s leadership also raised another $1.5 million over the same period. Combined, the party and the leadership contestants raised $3.1 million. The party hasn’t raised that much money in a fourth quarter since 2014.

I broke down the NDP leadership fundraising in greater detail last week:

That makes these numbers look better for the NDP — but the central party will not get to touch most of the money raised by the contestants. Unless they’re able to run surpluses that are returned to the party, the leadership contestants’ fundraising does not quite help the NDP’s own financial crunch.

The Bloc Québécois raised $652,000 from 4,500 contributions in the fourth quarter. That is the party’s worst fourth quarter since 2021 — the previous election year. Despite the poor showing in the quarter, the Bloc set its own fundraising record for the year at $2.2 million.

This means that three of the four major parties had record-breaking fundraising years. In all, the four parties raised $86.2 million, far surpassing the previous record of $70.3 million set in 2015. A lot of money was sloshing around in party coffers in this past election year.

There’s usually a big drop-off in post-election years. Since 2006, the year following an election has seen an average drop-off of about 33% in total fundraising, all parties put together. But if repeated in 2026, that would still represent roughly $57 million in party fundraising — enough to rank as the sixth-highest in the last 22 years. Part of that is inflation, but only a small part. The $33 million raised in 2006 would be the equivalent of $49 million today, according to the Bank of Canada inflation calculator.

Simply put, the main reason for the record-breaking fundraising in 2025 is that parties have gotten better at raising cash. Whether they’ve gotten any better at spending it is another question.

Now, to what is in this week’s instalment of the Weekly Writ:

News on a series of federal and provincial byelections we should expect to see in Toronto over the next 6-to-12 months. Plus, leadership news from Calgary, Quebec and PEI.

Polls show the Liberals widening their lead over the Conservatives and moving deeper into majority territory. Plus, new provincial polls out of Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta.

#EveryElectionProject: Quebec premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau drops the writ for a winter election in 1923.

The first Weekly Writ of the month is free to all subscribers. If you haven’t already upgraded and would like to get access every week please upgrade today:

NEWS AND ANALYSIS

Byelections! Get your byelections here!

It seems like Toronto is going to experience a series of rolling, cascading provincial and federal byelections over the next six-to-12 months.

And, of course, we’re here for it.

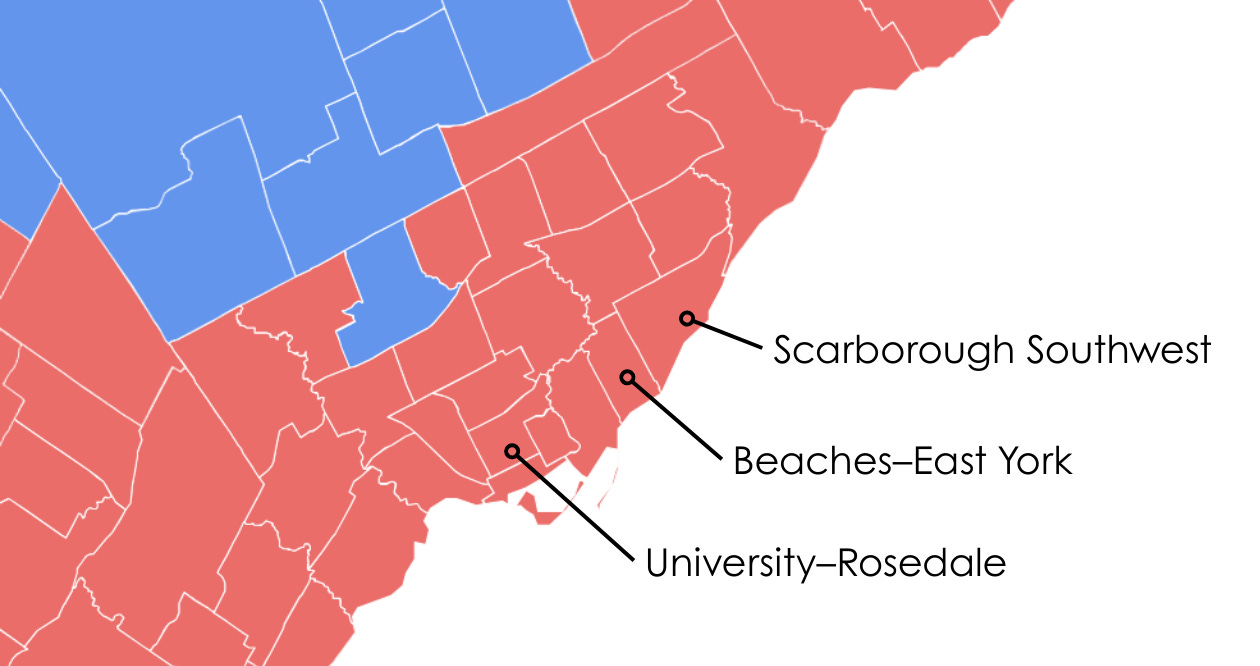

We already knew the federal byelection in University–Rosedale was on the docket following Chrystia Freeland’s resignation last month. The window for calling that byelection is currently open and will stay that way until July 8.

However, it seems likely that the Liberals will not wait too long to drop the writ. The Liberals are only a few seats shy of a majority in the House of Commons and so have a pretty strong incentive to fill their vacancies as soon as possible. The nomination on Saturday of Danielle Martin, a family physician with a high profile in the medical world, suggests the byelection call is relatively imminent — it’s rare for a governing party to announce nominations well in advance of a byelection, particularly when it is a seat where they are the incumbent. They won’t want to leave Martin in future-candidate limbo for too long.

The resignation of Bill Blair on Monday, however, adds a few more days to the time table. Blair is off to be the high commissioner to the United Kingdom and has vacated his seat of Scarborough Southwest. There’s a small delay between the vacancy of a seat and the earliest a government can drop the writ, which means the window for calling the byelection in Scarborough Southwest opens on February 13 and closes on August 1.

That the Liberals plan to call that byelection soon was made plain on Tuesday when it was announced that Doly Begum, one of the deputy leaders of the Ontario New Democrats and the MPP for the provincial riding of Scarborough Southwest, was resigning her seat at Queen’s Park to run as the federal Liberal candidate in Blair’s old riding. Here again, the Liberals will not want to leave Begum idling on the sidelines for very long.

This means we have at least two federal byelections likely to be called in a few weeks (assuming the Liberals intend to have University–Rosedale and Scarborough Southwest vote on the same day).

Begum’s resignation means that Scarborough Southwest will also have to hold a provincial byelection within the next six months.

And when that byelection is called, the clock will start ticking on another byelection.

Nate Erskine-Smith, the Liberal MP for Beaches–East York, has declared his intention to run as the Ontario Liberal candidate in the provincial Scarborough Southwest byelection, whenever that is called. The runner-up in the 2023 Ontario Liberal leadership is preparing for another run for the leadership of the party. Should he get the OLP nomination in Scarborough Southwest, he will have to resign his seat in the House of Commons when the writ is dropped on the provincial byelection.

So, to sum up, Blair’s resignation will cause a byelection in the federal riding of Scarborough Southwest, which, because Begum has resigned to run as the Liberal candidate, will cause a byelection in the provincial riding of Scarborough Southwest, which will then cause a byelection in the federal riding of Beaches–East York, assuming Erskine-Smith secures the OLP nomination.

It’s a fun little game of byelection dominoes.

The three federal byelections are unlikely to be very competitive. The Liberals won Scarborough Southwest by 30.9 percentage points, University–Rosedale by 40.5 points and Beaches–East York by 44.2 points. On the list of ridings the Liberals won by the biggest margins in 2025, Scarborough Southwest ranks 43rd, University–Rosedale ranks 20th and Beaches–East York ranks eighth. In other words, only in a 2011-style catastrophe would the Liberals be expected to lose even one of these three ridings.

Undoubtedly, that’s why the Liberals have been able to attract candidates of the calibre of Martin and Begum for these seats — they’re shoo-ins to win.

The provincial byelection in Scarborough Southwest, however, could prove interesting.

The Ontario New Democrats won the seat with 42.9% of the vote in the last election, beating the Progressive Conservatives by 12.2 points. The Liberals finished third with 22.9%.

The NDP’s incumbents really bucked the trend in the last election, maintaining far more of their vote from the 2022 election than did candidates in other parts of the province.

In Scarborough Southwest’s four neighbouring ridings, for example, the NDP lost an average of 11.4 points. Begum’s support, by contrast, dropped by just 4.8 points. With Begum no longer on the ballot, the NDP might struggle to maintain their 42.9% of the vote from the 2025 provincial election. In the Toronto riding of Parkdale–High Park, where the NDP’s Bhutila Karpoche did not run for re-election last February, the NDP’s support dropped by nearly nine points. If the same thing happens in Scarborough Southwest, the NDP could drop to around 34% support — a number that would puts them in range of being overtaken by the PCs or Liberals.

That possibility could become more likely if the resignation of Begum causes the Ontario NDP to take a broader hit. The loss of a deputy leader (to the federal Liberals, no less) does not reflect well on leader Marit Stiles, who herself only squeaked by with a 68% vote of confidence in last year’s leadership review. A downward spiral for the ONDP could make it harder to recruit a quality replacement for Begum and open up the seat for either the PCs or the Liberals.

The drama from these byelections could thus come at the provincial level rather than at the federal scene. But one way or another, voters in Toronto will have their fill in 2026.

ELECTION NEWS BRIEFS

POILIEVRE LEADERSHIP REVIEW - In case you didn’t see it already, Pierre Poilievre earned 87.4% on his leadership review at the Conservative convention in Calgary on Friday. This surpassed the 84% that Stephen Harper received at the party’s previous leadership review in 2005. It’s a number that suggests that Poilievre’s leadership faces no serious threat from within his own party’s membership base.

MILLIARD TO BE ACCLAIMED? - Mario Roy, the only other candidate to declare his intention to run for the Quebec Liberal leadership, was not yet been ruled eligible by the party to run as a candidate, which seemingly leaves the path open to Charles Milliard to be acclaimed as leader later this month. Milliard finished a very close second to Pablo Rodriguez in the PLQ’s leadership race last year. Roy finished last in that contest with just 0.8% support while accruing a campaign debt that he has yet to pay off, the sticking point that seems to be blocking his official entry into the race.

NEW PREMIER INCOMING - On Saturday, the PEI Progressive Conservatives will choose their new leader and the next premier of Prince Edward Island. The two contestants in the race are Rob Lantz and Mark Ledwell. Lantz stepped in as premier and interim PC leader after Dennis King’s resignation in early 2025 and had to vacate the premier’s office to run for the permanent leadership. Ledwell, a lawyer, does not hold a seat in the legislature and lags behind Lantz in caucus support. The next election in PEI is not scheduled until October 2027.

POLLING HIGHLIGHTS

Liberals widen lead over Conservatives

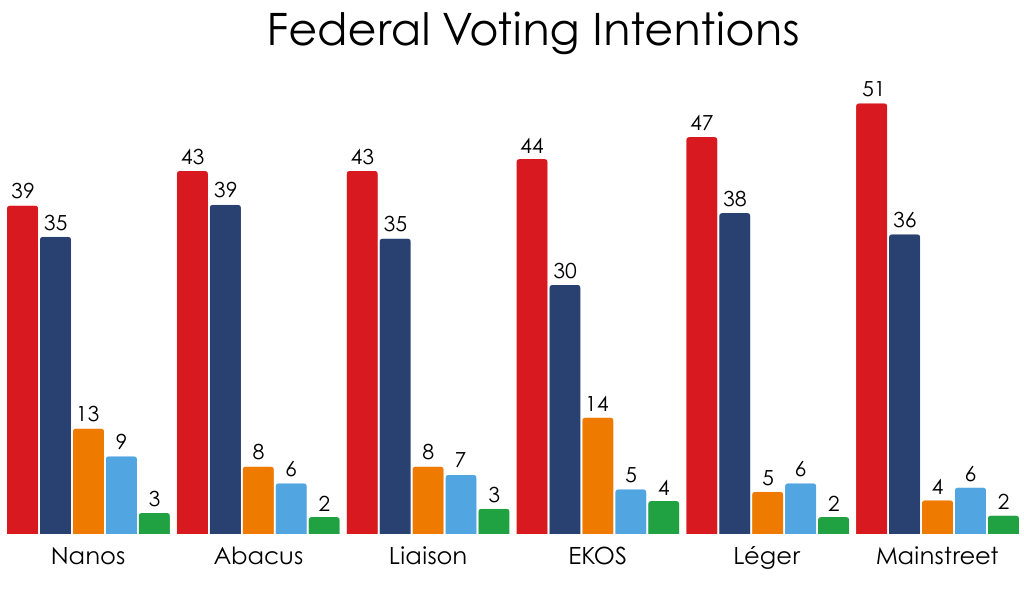

Polls published over the last week have shown a significant amount of divergences for some of the parties, but the general picture is the same: the Liberals are leading over the Conservatives, and by a wider margin than in the last few weeks and months.

The polls come from Abacus Data, Léger, Liaison Strategies, Nanos Research, Mainstreet Research and EKOS Research.

All six polls show the Liberals leading, though the margins vary from as few as four points to as many as 15 points. The Liberals have between 39% and 51% in these six polls, with the Conservatives scoring between 30% and 39% and the NDP between 4% and 14%. Those are some pretty big spreads.

But the trend is pretty clear across these polls. The Liberals are up in all of them compared to when these pollsters were last in the field prior to Mark Carney’s Davos speech in January. There is no consensus on where that gain has come from, however, with both the Conservatives and NDP up, holding or down in these polls.

The two polls that stand out in this group come from EKOS and Mainstreet — and for different reasons. EKOS has the Conservatives quite a bit lower than everyone else, while Mainstreet has the Liberals quite a bit higher. There are some asterisks that come with both of these polls.

The last time we heard from EKOS in mid-November, it had the Conservatives at just 33% at a time when other pollsters had the Conservatives between 36% and 41%. So, it isn’t surprising to see that EKOS is again on the lower side for the Conservatives. The trend is more important than the individual number. As with the other pollsters, the margin between the Liberals and Conservatives has widened for EKOS.

For Mainstreet, there has been a change in methodology between this poll and its previous release in mid-December. That previous poll included both IVR (interactive voice response) and SMS text-messaging for the sample. This new poll did not include an SMS component. That change could explain the huge swing between this poll and the previous one (the Liberals are up 10 points and the Conservatives are down 6.5 points). Another factor could be the rather Herculean weighting that has been applied to this poll to account for the very small sample of young voters. Mainstreet’s release suggests the sample of 18-to-34 year olds was just 55 respondents (MOE +/- 13%) and was weighted up to 231. That kind of weighting has the potential to amplify errors that are more likely when demographic sub-samples are small.

But, again, the broader signal from these polls is pretty clear — the Liberals are up and doing better than they were doing just a few weeks or months ago. It’s not so much that the Conservatives are slumping (Léger even has them up two points) but that the Liberals are enjoying a bump. It’s enough of a bump to push them safely into majority territory.

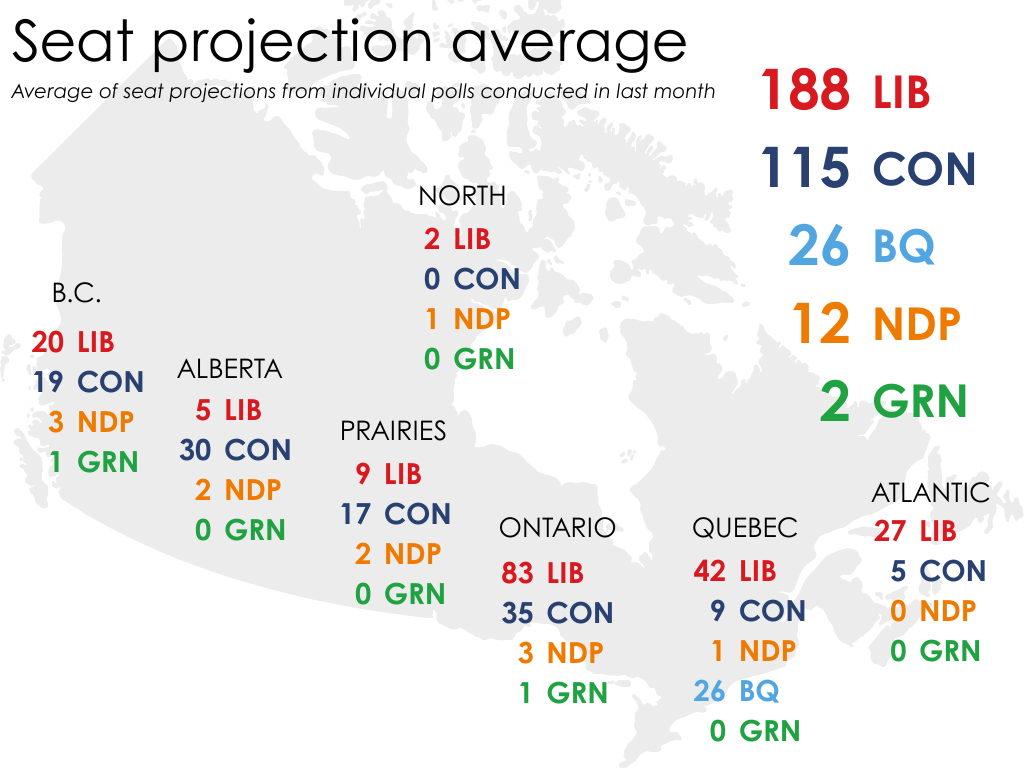

Notably, with the sole exception of the Nanos poll, each of these polls would produce a Liberal majority if their results were reflected at the ballot box. On average, these numbers give the Liberals 188 seats to just 115 for the Conservatives. The Bloc and NDP trail with 26 and 12 seats, respectively.

Much of this majority is built on Ontario, where the Liberals have made the most gains since last week’s projection. In fact, the Liberals have actually dropped seats in the projection in B.C. and the Prairies, but had those losses more than compensated for by significant gains in Ontario (and, to a lesser extent, Atlantic Canada).

POLLING NEWS BRIEFS

IS THE CAQ BACK? - Polling by Léger suggests that the next election in Quebec could be far more competitive than expected if Christine Fréchette becomes the next leader of the CAQ. The poll found the Parti Québécois leading with 32% support against 26% for the Liberals, 17% for the CAQ, 14% for the Conservatives and 7% for Québec Solidaire. With Fréchette as CAQ leader, however, the CAQ leapfrogs into second with 25%, with the PQ and Liberals nudged down to 30% and 21%, respectively. If Bernard Drainville instead wins the CAQ leadership, the CAQ would fall further behind. The poll suggests that Quebecers have favourable views of Fréchette and unfavourable ones of Drainville, and that CAQ voters overwhelmingly prefer Fréchette to Drainville. The poll also finds low support for Quebec sovereignty at just 29%.

UCP LEADS IN ALBERTA - Léger also had some new numbers out of Alberta, where the United Conservatives were leading with 50% support against 37% for the New Democrats. Compared to October, this represented a six-point bump for the UCP. Only 18% of Albertans said they think Alberta should become an independent country, while another 5% said it should join the United States. Fully 71% said it should remain a part of Canada.

NDP LEADS IN B.C. - Léger was in the field in British Columbia, too. The B.C. NDP led in the poll with 44%, followed by the B.C. Conservatives at 38%, the Greens at 9% and OneBC at 6%. Compared to October, this represented a four-point drop for the NDP. The Conservatives were unchanged. The poll found that no candidate for the leadership of the Conservatives was very or somewhat familiar to more than a fifth of British Columbians. No more than 3% of respondents to the poll said that any of the candidates were “very familiar” to them.

12-MONTH ELECTORAL CALENDAR

February 7: PEI Progressive Conservative leadership

Candidates: Rob Lantz, Mark Ledwell

February 23: Quebec provincial byelection in Chicoutimi

March 14: Quebec Liberal leadership

Candidates: Charles Milliard

March 29: Federal NDP leadership

Candidates: Rob Ashton, Tanille Johnston, Avi Lewis, Heather McPherson, Tony McQuail

April 12: Coalition Avenir Québec leadership

Candidates: Bernard Drainville, Christine Fréchette

May 11: Municipal elections in New Brunswick

May 30: British Columbia Conservative leadership

Candidates: Bruce Banman, Iain Black, Sheldon Clare, Caroline Elliott, Kerry-Lynne Findlay, Yuri Fulmer, Warren Hamm, Darrell Jones, Peter Milobar

October 5: Quebec provincial election

October 17: New Brunswick Progressive Conservative leadership

Candidates: Daniel Allain

October 17: Municipal elections in British Columbia

October 26: Municipal elections in Ontario

October 28: Municipal elections in Manitoba

November 2: Municipal elections in Prince Edward Island

November 9: Municipal elections in Saskatchewan

November 28: Nova Scotia Liberal leadership

Byelections yet to be scheduled

CA - University–Rosedale (to by called by July)

CA - Scarborough Southwest (to be called by August)

ON - Scarborough Southwest (to be called by August)

CA - Edmonton Riverbend (resignation pending)

CA - Beaches–East York (potential resignation pending)

AB - Calgary Shaw (resignation pending)

Party leadership dates yet to be set

Federal Greens (Elizabeth May announced on August 19, 2025)

Ontario Liberals (Bonnie Crombie announced on September 14, 2025)

ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

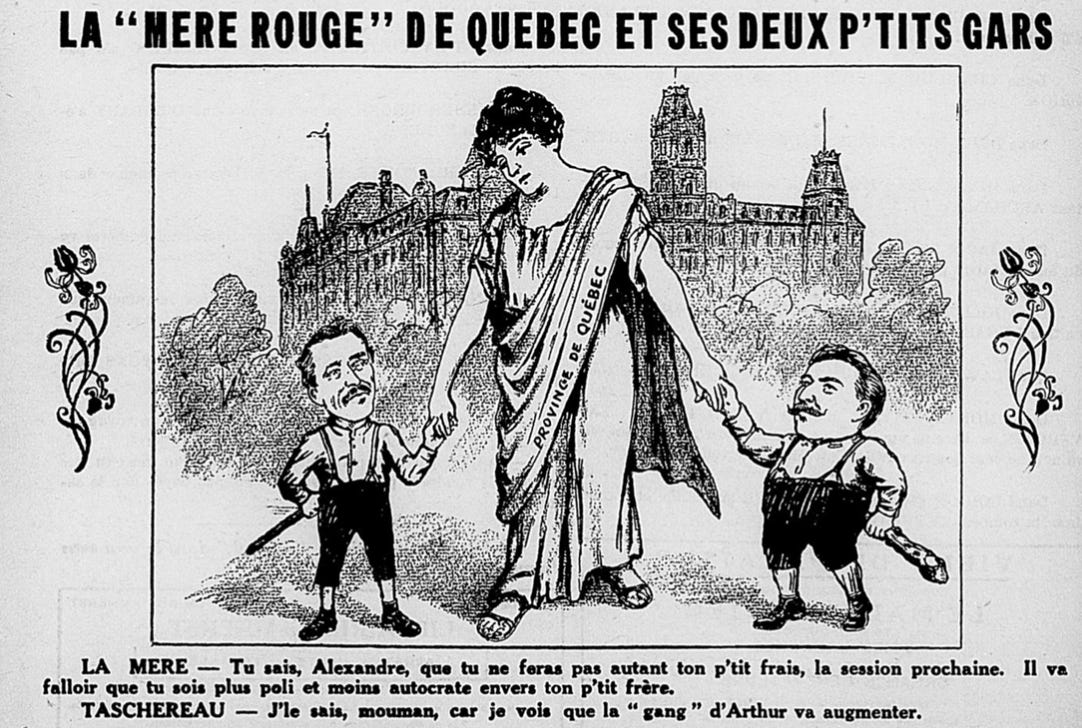

Taschereau’s first win and a Conservative comeback

February 5, 1923

When Louis-Alexandre Taschereau replaced Lomer Gouin as premier in 1920, the Quebec Liberals had already been in power since before the turn of the century. Taschereau had some big electoral shoes to fill, as Gouin had won four consecutive elections. But, then again, beating Conservatives in Quebec wasn’t all that tough at the time.

The imposition of conscription during the First World War by Robert Borden’s Union (but largely Conservative) government poisoned the well for Conservatives in Quebec. The party only managed five seats in the 1919 provincial election and was entirely shutout in the 1921 federal vote.

While crippling for the federal Conservatives, that sweep in 1921 was actually a godsend for the Quebec Conservatives and their leader, Arthur Sauvé. With the federal Conservatives now so weak, Sauvé was able to take control of the provincial organization of the party. The Quebec Conservatives built up their own organization and detached control of the party from Ottawa. It gave the Quebec Conservatives a distinct voice and some much-needed separation between themselves and Arthur Meighen, who had succeeded Borden as federal party leader. He had also been one of the central figures in the push for conscription.

Taschereau and the Liberals observed the rehabilitation of the Quebec Conservatives with some apprehension. Problems were starting to pile up on Premier Taschereau’s desk. Labour discontent and unemployment was growing in Montreal and Taschereau’s government had mishandled a few files and controversies in 1922. Sauvé and the Conservatives, despite forming a tiny opposition of five in the legislature, were making lots of noise.

The Liberals decided not to wait any longer. Constitutionally, they didn’t need to go to the polls before 1924 and would normally be expected to call an election for May or June in 1923. But Taschereau didn’t want to give the Conservatives more time to get off the mat. A winter election would make it all the more difficult for the Conservatives to organize outside of Montreal, where they already had some strength. The harsh winter climate would make it difficult for opposition candidates to tour the rural and remote ridings that made up the vast majority of seats in Quebec. If they couldn’t get better known locally, the incumbent Liberals would have the advantage. The election was set for February 5, 1923.

After nearly 26 years in office, the Liberals didn’t have much new to present to the electorate. But they still managed to publish a 300-page manifesto lauding their achievements, believing that it would make the case for re-election. Especially when contrasted to the Conservative platform, which Taschereau said was “made up of nothing but malevolent criticisms and of meaningless administrative reforms.”

For the first time in decades, the Liberals had some reason to be concerned. They knew the Quebec City region was solid for them — Taschereau was from the area — but that didn’t prevent the premier from being heckled at his first major rally in the city. Opponents snuck into the crowd at the event, making noise only when Taschereau finally made it to the stage. (They didn’t want to get thrown out early by heckling the warm-up acts.) But the patrician Taschereau could give as good as he got. When the hecklers began chanting “We want cheap liquor!”, the premier responded with “it’s obviously cheap enough for you now!”

If Quebec City was relatively solid and the winter snows could be expected to hobble the Conservative campaign in the regions, Montreal was another matter. The city was Sauvé’s territory. Newspapers, including English-language ones, were more hostile to the Liberals in Montreal than the were in Quebec City. The working classes in the city were hostile to the Liberals and had lined themselves up behind the Conservatives (who had under their banner some labour candidates). The business community was peeved at Taschereau’s creation of a Liquor Commission that funnelled alcohol profits to government coffers. And municipal leaders were annoyed that the Liberals had decided to build a boulevard that would cross the entirety of the island but left the bill with the local municipal authorities.

Though taken by surprise, the Conservatives were still in better shape than they had been in for years. Unlike some past elections, they were able to run a nearly-full slate that included some impressive new recruits, including future leaders Camillien Houde and Maurice Duplessis. Their campaign denounced the timing of the election, what they argued was the waste in Taschereau’s administration and the premier’s autocratic tendencies.

But supporters of the party understood that defeating the Liberals probably wasn’t in the cards. Henri Bourassa, editor of Le Devoir and one of the chief critics of the Liberal government, assailed Taschereau in the pages of his newspaper. But he still only asked his readers to elect a robust opposition.

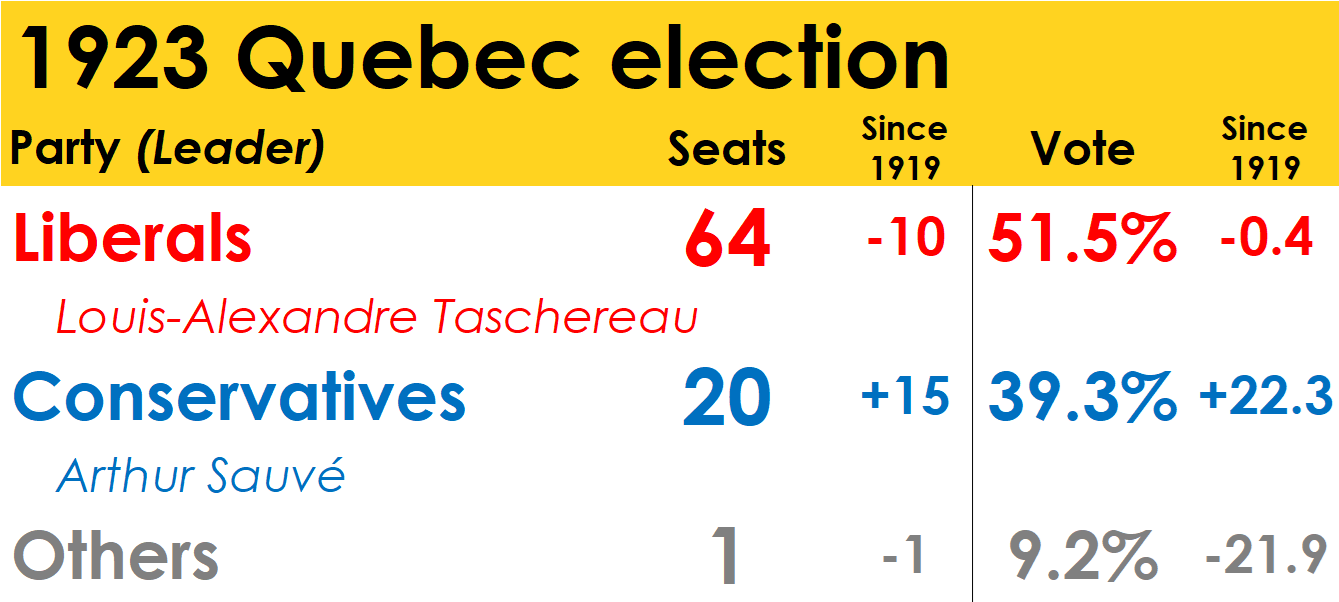

The Liberals lost 10 seats in the expanded legislature, taking 64. Their share of the vote held up at 51.5% but was concentrated primarily outside of Montreal.

The Conservatives increased their vote share by 22 points, winning 39.3% of the vote. They picked up 15 seats and elected 20 overall, though only four of them were outside of the Montreal area — and 13 were on the island itself.

(The National Assembly of Quebec, from which these results were sourced, provides a simplified accounting of the results of the election in 1923. The “Others” above included those running as Independents, Independent Liberals, Labour or Farmer candidates, among other partisan banners.)

The province’s politics had become competitive once again, but the Liberals were able to withstand the Conservative comeback and avoid the fate of many governments in the rest of the country that went down to defeat in the aftermath of the First World War.

Taschereau won his first electoral test. It would be far from his last. And while the Conservatives had built themselves back up into a viable political organization, they’d never win more seats than they did in 1923 — at least, not under the Conservative banner.