The Weekly Writ for Sept. 7

Poilievre cruising to victory, who's up and down in Quebec's election and a last-hurrah-that-wasn't for Joey Smallwood.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Wednesday morning.

Lots to cover in the latest instalment of the Weekly Writ, as I take a look at the standings in the Conservative leadership race that is coming to an end and the slate of candidates in the Green leadership race that is just getting started.

Then, I break down the newest polls in Quebec, as well as a new national survey and another on whether Albertans want out.

Finally, I profile a riding that is emblematic of the challenges the Quebec Liberals face in this campaign, before concluding with the election that should have concluded Joey Smallwood’s storied career as premier of Newfoundland.

Let’s get to it.

IN THE NEWS

Poilievre heading to victory on Saturday

The Conservative leadership race has been little more than a get-out-the-vote operation for the last couple of months. With members already signed up and the debates (at least the ones in which all the candidates participated) long behind us, this was a campaign that featured very little persuasion. It was all about signing up the most people who already agreed with the contestants for the Conservatives’ top job.

Accordingly, we haven’t seen much change in the Conservative Leadership Index. The endorsements stopped coming in big numbers months ago and the polls have been consistent. Our last taste of fundraising data is going to come at the end of the week, but it is unlikely to change much.

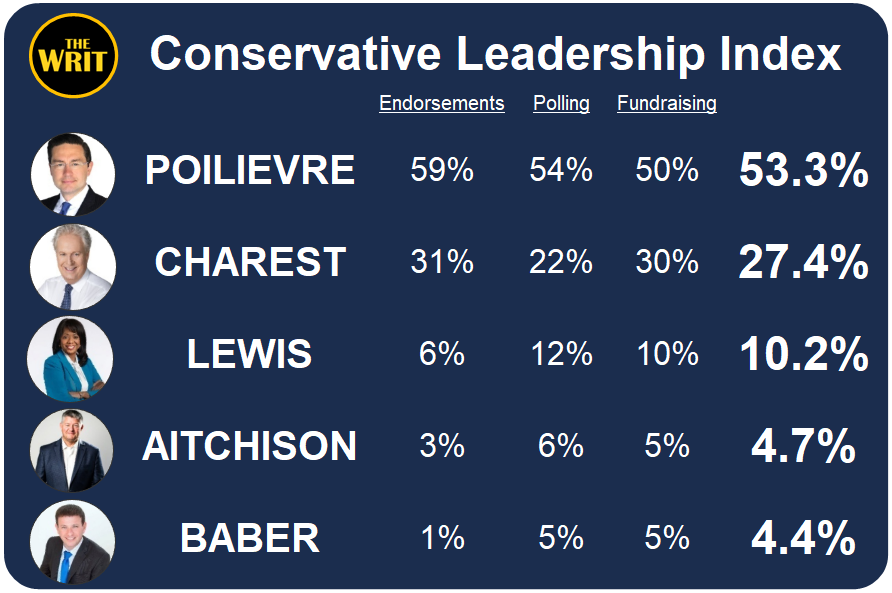

Pierre Poilievre finishes the campaign much where he started — in the front runner position and in first-ballot-victory territory. The CLI estimates a result of 53.3% for Poilievre on the first ballot. Jean Charest comes second with 27.4%, followed by Leslyn Lewis at 10.2%.

Scott Aitchison and Roman Baber bring up the rear with 4.7% and 4.4%, respectively.

Poilievre could do far better than 53%. The polling we’ve seen (the most recent numbers come from Ipsos) have always put Poilievre ahead by a big margin among Conservative supporters, but we know that he is likely to be even more popular among Conservative members.

His fundraising might also be under-estimated as the second quarter filing with Elections Canada was missing a lot of donations to leadership contestants that the Conservative Party hadn’t yet been able to process. And Poilievre has a huge lead in the number of individual contributors, who have donated less per contribution to his campaign than the smaller number who donated to the Charest campaign.

It would not surprise me to see Poilievre clearing not only 50% but 60% on the first ballot. His campaign swamped the existing membership with new sign-ups, and those existing members were probably already in the bag for him. The odds of a landslide victory are good.

On the other hand, there is the possibility that Poilievre does not win on the first ballot.

First, the points system that awards equal weight to all 338 ridings is likely to penalize Poilievre, who has a lot of support in Western Canada, and boost Charest, who has a disproportionate amount of his support in Quebec and Atlantic Canada.

Based on fundraising data, I estimated that the point system could penalize Poilievre by about three to five percentage points, while boosting Charest by five to eight points. The CLI, though, already takes this into account.

But when you look at the ballot and who is on it, getting Poilievre to 50%+1 isn’t necessarily easy. The CLI awards Baber and Aitchison about 9% of the combined points. It’s possible they will under-shoot that mark, but Baber in particular has had a decent number of individual contributors.

Lewis has 10% in the CLI, but considering she earned 20% of the first round points in the 2020 leadership race it seems more likely than not that she will be able to beat 10%.

Even if she doesn’t, that gives Lewis, Aitchison and Baber about 19% of the points, meaning Charest needs to earn at least 31% of the points to deny Poilievre a first ballot victory. That might be a high bar for him to meet, but it isn’t completely out of the question — and if Lewis does better than 10% then it simply reduces the amount of points Charest needs to get to keep Poilievre under 50%.

Getting Poilievre significantly below 50%, however, takes some imagination. And it would only delay his inevitable victory, as he is certainly going to take the lion’s share of second choice support from both Baber and Lewis (and benefit the most from ballot exhaustion). If Poilievre doesn’t win on the first ballot, he probably wins on whatever ballot eliminates Baber. If he needs them, Lewis’s voters will finish the job.

Does Charest have a chance? Theoretically yes, but it isn’t a good one. He’d need the points system to boost him by 10 or 15 points, Poilievre’s supporters to fail to submit their ballots in big numbers and for both Baber and Lewis to under-perform while Aitchison over-performs.

It is difficult to imagine more than one of these things happening, let alone all of them. Poilievre’s sign-ups have been so broad that he is unlikely to be significantly penalized by the points system. His supporters seem quite enthusiastic. And if one had to bet who is likely to over-perform out of the bottom three, you’d expect it to be Lewis and/or Baber, not Aitchison.

In fact, it might be as likely for Charest to finish third, behind Lewis, as it would be for him to finish first. Lewis beat her expectations by a fair bit last time — if she approaches 20% again, Charest isn’t a shoo-in to do much better.

In other Conservative news, interim leader Candice Bergen has announced she will not be running for re-election again. Bergen has been a Manitoba MP since 2008 and won her Portage–Lisgar seat by 31 points (over the People’s Party) in last year’s election. I wouldn’t read too much into her decision and its timing, considering that Bergen would seem far more aligned with Pierre Poilievre’s politics than Jean Charest’s.

There will be plenty of Conservative leadership content coming from me over the next few days. Tim Powers, Chad Rogers and Stephanie Levitz will be back on the podcast tomorrow to give their last take on the race, and you can catch me on the CBC on Saturday night when the results are announced. I’ll also have an analysis of those results (and potentially a reaction podcast) out shortly afterwards.

Green leadership slate set

Last Wednesday, the Greens announced their slate of six candidates who will be contesting the party leadership. They are (along with their latest electoral activity):

Simon Gnocchini-Messier, who ran for the Greens in the Quebec riding of Hull–Aylmer in 2021, taking 3% of the vote.

Elizabeth May, leader of the party from 2006 to 2019 and MP for Saanich–Gulf Islands in British Columbia since 2011. She was re-elected with 38% of the vote in her riding in 2021.

Jonathan Pedneault, who hasn’t run for elected office before.

Anna Keenan, who ran for the Greens in the P.E.I. riding of Malpeque in 2021, taking 14% of the vote.

Chad Walcott, who ran for the Quebec Greens in the riding of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce in 2018, taking 7% of the vote.

Sarah Gabrielle Baron, who ran as an Independent in the Ontario riding of Durham in 2021, taking 0.4% of the vote.

There are two joint tickets in this race, with May and Pedneault pledging to lead the party together, as are Keenan and Walcott. But their names will all appear individually on the ballot and, presumably, how this would all work out will be dealt with after the race is over, as the party is not currently set up to have co-leaders.

I’m also not sure what it would mean if, say, Keenan finished first and Walcott finished sixth. Would it be seen as legitimate to then make Walcott the co-leader? And is there a potential vote split that could occur that could hurt these joint tickets?

That isn’t a minor point, since there will be a first round of voting that will eliminate two candidates on October 14. It would be awkward if one of the joint tickets features an eliminated candidate ahead of the November 19 second round of voting.

THIS WEEK’S POLLS

Quebec poll round-up

So far, polling in the Quebec election campaign has been pretty thin. But we have been getting a daily tracking poll from Mainstreet Research, which has been posted to the polling firm’s Twitter feed.

The numbers haven’t shown much variation, with the CAQ polling between 37% and 41% since the start, the Liberals between 17% and 20%, the Conservatives between 16% and 22%, Québec Solidaire between 12% and 13% and the Parti Québécois between 7% and 11%.

If we plot out the daily results, there aren’t really many strong trend lines.

According to Mainstreet, the PQ at least is heading in a positive direction, having started the campaign in the 7% to 8% range and lately being in the 9% to 11% range. The Conservatives and CAQ have been trending down.

But these are some gradual trend lines, and eventually they will hit the wall of electoral reality — the PQ might have started artificially low in Mainstreet’s polling, while the Conservatives started artificially high. If that’s the case, these trends are reversion to the mean, rather than anything actually happening on the campaign trail. À suivre.

If you missed it, Philippe J. Fournier and I chatted about the first week of the Quebec election campaign on a bonus subscribers-only episode of The Writ Podcast on Monday. Check it out here.

Segma also published a survey for Le Soleil and FM93 for the Quebec City region, finding the CAQ leading with 42.5%. The Conservatives were second with 25%, followed by Québec Solidaire at 16%. The Liberals and PQ were tied at around 6% apiece.

This is broadly in line with other surveys we’ve seen for the region, but of note is how well the Quebec Conservatives are doing among younger voters: they were virtually tied with QS for first place among those under the age of 35. Among voters over the age of 65, by comparison, the Conservatives were dead last.

That’s a notable script flip on the part of Éric Duhaime’s Conservatives. Traditionally, right-of-centre parties do best among older, not younger voters. The CAQ, for example, dominates the 55+ crowd in Quebec City. But Duhaime is appealing to younger voters, the kind of thing we’ve seen some hints of with the Poilievre campaign.

It’s an interesting new dynamic, though it does raise the question of what happens if traditionally Conservative-voting seniors, formerly part of the ‘establishment’, find themselves on the outs with the party they usually back. And older voters, of course, vote in bigger number than younger ones. Is the youthful right a higher turnout group than the youthful left? I guess we’ll find out.

Liberals, Conservatives neck-and-neck nationally

The latest Abacus Data poll puts the Conservatives at 33% and the Liberals at 32%, more or less exactly where they were in last year’s election. The NDP was third with 19%, followed by the Bloc Québécois at 7% (31% in Quebec, four points behind the Liberals), the People’s Party at 5% and the Greens at 3%.

So, if Poilievre does win he’ll become leader in a political climate that is nearly identical to what it was in September 2021. At the personal level, he starts out a little under-water with 22% of Canadians holding a positive impression and 27% holding a negative impression. In June 2020, a few months before that year’s Conservative leadership race, Erin O’Toole had a 15% positive to 21% negative rating.

Support for Alberta independence at 23%

As Danielle Smith fights off opponents to her Alberta Sovereignty Act, which would give Alberta (probably unconstitutional) powers to ignore federal law, a new survey from Research Co. suggests that not many Albertans are all that big on the whole sovereignty thing.

It found just 23% of Albertans strongly or moderately supporting Alberta becoming its own country, while 70% were opposed, including 61% of United Conservative Party voters.

Now, Smith, the perceived front runner in the UCP leadership race, has not said she would lead Alberta out of the federation (though she has said she’d give Canada just one last chance). But this survey does show that the appeal of her rhetoric has its limits.

Interestingly, Research Co. tested a number of options, including Alberta joining the United States and a number of Western provinces going it alone together. The least popular was becoming the 51st state (21%), while the most popular was a new nation spanning from the Pacific Ocean to Hudson Bay, which had 30% support.

Still a long way from “winning conditions”.

RIDING OF THE WEEK

Marquette (Quebec)

If the Quebec election campaign goes badly for the Liberals, they might have to defend themselves in seats that were once sure-things.

That brings us to Marquette.

This riding in the West Island includes Dorval, Lachine and the Montreal-Trudeau airport. Enrico Ciccone, a former NHL enforcer, won the riding for the Liberals in 2018 with 43% of the vote. The CAQ finished second in Marquette with 28%, followed at length by Québec Solidaire at 11%.

This part of Montreal has voted for the Quebec Liberals in every election since 1939 — so that’s a lot of history. Only when the English-rights Equality Party won the western portion of the modern riding in 1989 did this area not stick with the Liberals in its entirety.

Marquette is one of the ridings in which the Liberals rely on the non-francophone vote, which represented 54% of residents in the 2016 census. Normally, the Liberals can count on their anglophone base to give them a solid footing in a seat like Marquette, with their decent support among francophones putting them easily over the top.

But with the Liberals polling in the high-single-digits to low-teens among francophones, the Liberals can’t count on this equation working for them anymore.

Complicating matters is that the Liberals are having some trouble among non-francophone voters, at least when compared to their usual dominance. The most recent Mainstreet poll puts the Liberals at 52% among non-francophones, down from the 60% or 70% the Liberals can normally count on as their floor among this electorate.

The CAQ, at just 10% among non-francophones and at odds with the anglophone and allophone community over Bills 21 and 96, isn’t the party getting a boost from this Liberal slide. Instead, the Conservatives (who managed 2% in Marquette in 2018) registered 18% support in the Mainstreet poll among non-francophones.

There is the potential that in a seat like Marquette, the Conservatives could split the vote enough to let the CAQ move ahead.

Let’s do some simple math. If the Liberals have 52% support among non-francophones and non-francophones make up 54% of voters in Marquette, that gives the Liberals just 28% support. That’s not enough to win a seat. Adding their low support among francophones would bump them up to 33% in Marquette, or 10 points worse than Ciccone’s score in 2018.

That lines up with the 12-point drop Mainstreet records for the Liberals on the island of Montreal compared to the last election. The CAQ, meanwhile, is up nine points on the island. That total Liberal-CAQ swing of 21 points is more than enough to erase Ciccone’s 15-point margin of victory last time.

Ciccone is running for re-election while Marc Baaklini will be the CAQ candidate. As of today, there is no candidate listed for the Bloc Montreal or Canadian Party of Quebec, two parties running on a platform to protect anglophone rights. If they do put up candidates, the Conservatives might not be the only ones splitting the vote.

(ALMOST) ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

Newfoundland gives their hero a last hurrah, but he won’t stay away

September 8, 1966

(No general election has been held on September 7.)

It was supposed to be Joey Smallwood’s last hurrah. The voters planned to send him off in style, giving the man who brought Newfoundland and Labrador into Confederation his biggest landslide. It was the pinnacle of Smallwood’s political dominance of the province, which had in many ways become a one-party state.

There was more than just affection and, just maybe, fear that gave the Liberals such a big victory in the 1966 Newfoundland election. The economic mood of the province was upbeat and the future looked bright. In the months ahead of the election call, Smallwood announced a new fish plant here and the expansion of an iron ore plant there. He announced that more electricity power would be produced and that a new phosphorus industry was going to be developed.

There had been investment in education with free tuition for first-year students at Memorial University, which was also about to get a new faculty of medicine.

Why would Newfoundlanders want to ruin all that by doing something as silly as voting for the opposition?

James Greene, who led that small contingent of Progressive Conservatives on the opposition benches in the House of Assembly, resigned in January 1966, “pleading pressure of private business.”

His replacement was Noel Murphy, who had won his seat of Humber East in the 1962 provincial election — the first time the Liberals had failed to take it. A former medical officer for the Royal Air Force’s Newfoundland squadron, Murphy was aching for a duel with Smallwood.

Rumours were circulating that Smallwood might step aside before calling an election. In response, Murphy said that he didn’t “want him to resign from office undefeated and go down in history as a legend. I want him to be defeated at the polls and this is what the Conservative Party is working toward right now.”

“It’s about time that the people of Newfoundland realize that the Liberals are not the only ones capable of forming a Government.”

Smallwood wouldn’t step aside, at least not yet, and kicked off the three-week election campaign in August 1966.

The Liberal platform, which Smallwood dubbed “the greatest political document in Newfoundland’s political history”, was a 41-page booklet that included promises of 4,000 miles of newly paved and constructed roads, including a tunnel that would connect Newfoundland to Labrador (paid for by the feds). The Liberals would build and renovate hundreds of schools, expand the province’s health services and lower electricity costs.

Flush with cash, the Liberals printed 100,000 copies of the platform and stuck 50,000 of them into the mail for voters to peruse.

Smallwood also said that he was “positively preparing to step down as soon as these kiddies [young Liberal candidates] have made up their minds what they are going to do and are ready to do it.”

These “kiddies” included newly-minted cabinet ministers like Clyde Wells, 28, and John Crosbie, 35.

But in case voters weren’t feeling grateful to Joey and the Liberals, the premier who had easily won every election held since Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949 made it clear what a lack of gratitude could mean.

To the voters of Stephenville, where the U.S. Air Force had just shuttered an airbase, Smallwood wrote a letter:

The minute [the U.S.] left it became my job to save that part of Newfoundland from unemployment, destitution, dole, despair and finally the disappearance of much of its population…. Will you help me to do it? Or do you want to send me a message saying, “Stop. We don’t need your help.” … That will be the answer you will give me if you elect the Tory candidate, or the Independent Liberal candidate. If you want to send me a message saying: “Yes, Joe, we want you to keep on working hard for this District and the people in it,” the only way you can send me that message is to elect the Liberal Party’s candidate.1

Murphy and the PCs had little to fight back with and Murphy took to calling Smallwood a “tyrant” and a “dictator”. The New Democrats ran only three candidates and were led by Calvin “Tubby” Normore, who was taking on Smallwood in the riding of Humber West. According to the Canadian Press, this former amateur wrestler “was named leader of the New Democratic Party only three days after the election was called. He has no political background.”

There was some drama during the campaign when former Quebec premier Jean Lesage said that negotiations between Quebec and Newfoundland had included discussion of changing the borders of Labrador. Smallwood didn’t hold back, calling Lesage “a liar from head to toe”. The former premier eventually clarified that the negotiations didn’t include border adjustments.

By the end of the campaign, there was little doubt that Smallwood would win again. He had now upgraded his musings about retirement to “definitely”, and had even said his chosen successor would be Fred Rowe, the finance minister. All Newfoundlanders had to do was send Joey off into the sunset.

And that they did, giving the Liberals 39 of 42 seats and nearly 62% of the vote. The Liberals picked up five seats, reducing the Progressive Conservatives to just three seats, all of them in the St. John’s area. The NDP and various independent candidates were shut out.

Reflecting on the results, Smallwood said it was “a sobering victory because how am I going to measure up to such overwhelming confidence?”

To be fair, the Canadian Annual Review noted that “the opposition did not really offer a reasonable alternative government to the electorate, which can be explained, in part at least, by the fact that most of the truly promising young politicians have been attracted, by one means or another but basically by the guarantee of success, to the Liberal Party.”

Murphy went down to defeat in Humber East, beaten by future premier Clyde Wells. His campaign was also made all the more difficult by Smallwood deciding he would run in the neighbouring riding. Smallwood wasn’t going to take any chances by letting the leader of the opposition win his own seat.

It would prove to be Smallwood’s last victory. He eventually announced his retirement in 1969 but reversed his decision and ran for the leadership of the Liberals in order to block the candidacy of John Crosbie, one of his former “kiddies”. Smallwood beat Crosbie, split the party in two and met his defeat when, in 1971, Newfoundlanders finally did realize that the Liberals were not the only ones capable of forming government.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Writ Podcast will be dropping on Friday. As always, the episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. And don’t forget to subscribe to my YouTube Channel, where I post videos, livestreams and interviews from the podcast!

Smallwood: The unlikely revolutionary, by Richard Gwyn.

Re: the QCP among young people, I wonder if it is just a young people were against COVID restrictions more so they are now more inclined to vote QCP

What impact do you think Patrick Brown supporters will have? How many do you think voted for him anyways?