The Weekly Writ for July 6

What I missed while I was away and the 'tale of a job looking for a man'.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Wednesday morning.

I’m back from vacation — my first real vacation since before the pandemic — and I have a lot to catch up on. So, let’s jump right into it with updates on a series of leadership races across the country, along with some new polling data, a riding-profile-by-the-sea and the tale of perhaps the least known Conservative Party leader in Canadian history.

But first, let me pass along a word of thanks to my annual subscribers who are entering Year 2 of their subscription to The Writ. You backed me when I launched a year ago. It meant a lot then, and now that you’ve stuck around in big numbers it means even more to me now. Thanks so much! And now, onwards!

IN THE NEWS (while I was away)

John Horgan to step down

British Columbia’s John Horgan announced on June 28 that he would be stepping down as premier as soon as the B.C. New Democrats name his successor.

This comes after Horgan underwent treatments for throat cancer. He says he is currently healthy and cancer-free, but those treatments have taken their toll and spurred Horgan to re-think his priorities and what he will do with the rest of his life. You can’t blame him, and I wish him all the best.

Horgan will be staying on as an MLA for the rest of his term, but will be replaced as NDP leader and B.C. premier when the party holds a leadership vote in the fall.

His successor will be taking over a party in good shape. The B.C. NDP has been ahead in the polls over the last few months, even after the opposition B.C. Liberals selected a new leader in Kevin Falcon back in February. It has been outpacing the B.C. Liberals in fundraising by a margin of more than two-to-one.

But whoever replaces Horgan will have big shoes to fill. His victory in the 2020 provincial election made him the only incumbent NDP premier to win an election and the party’s 48% vote share was its best ever. With 57 of 87 seats, the NDP has a solid majority but will be carrying the baggage of seven years in office by the time next scheduled election is held in 2024.

Still, this is perhaps the best political job currently up for grabs. The next leader of the B.C. NDP will immediately become the premier of the third-largest province in the country with a few years to go before the next election and every chance to win it. By contrast, the next leader of the United Conservative Party will become Alberta premier, but could lose that job within a year. The next leader of the federal Conservative Party could have to sit on the opposition benches for another three years with no guarantee of a promotion after that.

I’m looking forward to seeing who is going to throw their hats in the ring over the next few months. This is a prize worth fighting for.

Pierre Poilievre still odds-on favourite to win

MORNING UPDATE: The news that Patrick Brown has been disqualified from the Conservative leadership race broke after your correspondent was sleeping in his comfy, comfy bed. Obviously, this changes everything. My thoughts are here. What’s below has been left unchanged.

With the Conservative membership cut-off now behind us (the party says there will be some 675,000 members eligible to vote), the race has quieted down a little. Pierre Poilievre continues to amass endorsements that now represent a majority of the Conservative caucus, while Patrick Brown and Jean Charest try to keep themselves in the conversation.

A couple polls were released in the last few weeks showing the same sort of strength for Poilievre over Charest among Conservative voters (not necessarily members). So, the Conservative Leadership Index hasn’t changed much:

Poilievre leads with 47.7% in the Index, followed by Charest at 28.7%. Leslyn Lewis comes in third with 11%, with Brown at 6.6%, Scott Aitchison at 3.7% and Roman Baber at 2.3%. (Caution: I continue to believe that the Index is under-estimating Brown’s support.)

The methodology for the CLI can be found here.

The next important milestone for the Index will be at the end of the month, when the second quarter fundraising reports will be published by Elections Canada. That will be our best indication of where things stand, as the first quarter reports only captured the first weeks of the leadership contest.

It will be particularly revealing to see how Charest and Brown have done over the past few months in fundraising — and a real sign of the relative strength of their two campaigns, as well as a hint at Poilievre’s chances of winning a first ballot victory.

Two women take over NDP leaderships

Two provincial New Democratic parties chose women as their new leaders over the last few weeks, with Claudia Chender and Carla Beck taking over the Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan NDPs, respectively.

Chender, a Halifax-area MLA since 2017, was acclaimed leader of the Nova Scotia NDP on June 25, and will head-up the third party in the provincial legislature and take over from former leader Gary Burrill. Polls put the NDP in the mid-to-low 20s in support in the province and in a race with the leaderless Liberals for second spot. Nova Scotia is next scheduled to hold an election in 2025.

In Saskatchewan, Beck becomes the first permanent female leader of the NDP in the province. Beck, who has been a Regina-area MLA since 2016, easily won the leadership vote with about 68% of the nearly 5,000 ballots cast. Kaitlyn Harvey, who did not have a seat in the legislature, was her only opponent.

The lopsided result is new for the Saskatchewan NDP. With the exception of Roy Romanow’s victory by acclamation in 1987, no leader of the party has won the job with more than 60% of the vote since the days of the old CCF.

The NDP faces an uphill climb ahead of the next election in 2024 as it continues to trail the governing Saskatchewan Party by a significant margin in the polls.

Green leadership dates set

The leadership news keeps on coming, with the dates for the federal Green Party leadership finally set.

The dates to keep in mind:

August 5: Deadline to apply to be a contestant

August 31: Official contestant list revealed

September 14: Deadline to be eligible to vote in the first round

October 14: First round voting ends, results revealed

October 19: Deadline to be eligible to vote in the second round

November 19: Second round voting ends, winner named

You’ll note there are two rounds of voting in this timeline. That’s because the Green Party will hold two rounds if there are more than five candidates in the running. If that’s the case, the first round will whittle the list down to the top four, who will go on to the second round. If there are five or fewer contestants, then all contestants will go on to the second round (which, I guess, becomes the only round).

In both rounds of voting, a ranked ballot will be used.

One sign of the financial difficulty the party finds itself in is that 50% of the money raised by contestants will go into party coffers — far higher than the share of fundraising in the Conservative leadership race that goes to that party.

The Greens are coming off an awful result in the 2021 federal election that saw former leader Annamie Paul and one of their incumbent MPs defeated after months of ugly internecine fighting. We’ll see if this contest can give the party a chance to reset.

PCs win two New Brunswick byelections

Finally, I wanted to close the loop on the podcast I did with Jacques Poitras about two byelections that were being held in New Brunswick on June 20. The results were good news for the governing Progressive Conservatives.

In Southwest Miramichi–Bay du Vin, Mike Dawson of the PCs was able to hold the seat with a gain of just over four points from his predecessor’s performance in 2020. The Liberals, though, picked up 14 points, while support for the People’s Alliance plummeted more than 20 points. The Greens did not run a candidate here in 2020, but took nearly 5% this time.

The big change, though, took place in Miramichi Bay–Neguac, where Réjean Savoie won the seat for the PCs with a gain of over 11 points. The Liberals fell nine points, while the People’s Alliance dropped eight. The Greens picked up five points to finish third.

That shift in Miramichi Bay–Neguac could be chalked up to the quality of the PC candidate (a former MLA), but nevertheless these wins represent gains for the PCs across the board. The collapse of the People’s Alliance seems to have helped the PCs, though they did not necessarily gain all of the support the People’s Alliance shed.

The Liberals were down in one seat and up in the other, so it is hard to discern a trend. But losing a seat they had held is a big setback, particularly since it comes in a riding with a significant francophone population. The linguistic divide between the Liberal, francophone north and the PC, anglophone south has been pretty stark in recent years — this is a reversal of that trend.

THIS WEEK’S POLLS

Inflation nation

The weekly polling by Nanos Research now identifies inflation as the top (unprompted) issue for Canadians at 19%, beating out jobs and the economy at 14% and the environment at 11%. The COVID-19 pandemic, which was once the top issue for nearly 50% of Canadians, has dropped to just 1.4%.

Concern about inflation has nearly quadrupled since the beginning of the year, the only issue that has really taken off as concern with the pandemic has subsided.

Justin Trudeau’s support as the preferred prime minister, though, has held steady at around 30%. Interim Conservative leader Candice Bergen is second with just under 20%, while Jagmeet Singh of the NDP stands at 17%.

Coalition Avenir Québec still on track for a win

Newly-released polling by the Angus Reid Institute shows the ruling Coalition Avenir Québec with a big lead in the province ahead of the October provincial election. The poll itself was conducted in mid-June, but the results were released in detail on Tuesday.

The CAQ topped the poll with 35%, followed by the Quebec Conservatives at 19%, the Quebec Liberals at 18%, Québec Solidaire at 14% and the Parti Québécois at 10%.

The chart above shows why the CAQ is on track for another majority government, even if this survey (as is often the case with the ARI) has CAQ support lower than we’ve seen elsewhere. The party has very strong support in Montérégie and Estrie, regions to the south and east of Montreal that contain a lot of seats. The opposition is also greatly divided in the other regions, meaning the CAQ is in a strong position to sweep nearly everything off the island of Montreal (where the Liberals lead) and in and around Quebec City (where the Conservatives are competitive).

The Writ’s focus is going to turn more to the upcoming Quebec election as voting day approaches.

RIDING OF THE WEEK

Gaspé (Quebec)

And that brings us to the Riding of the Week, where I highlight one riding that will be hotly contested in an upcoming election. To kick-off the Quebec election season, I’m heading to where I just left: Gaspé.

Yes, my vacation brought me to the Gaspésie, a place that has always felt like home even though I haven’t lived there since I was three years old. But I’ve always made a point of returning — because it is a magical place.

The Gaspésie is close to my heart not only because it is where I was born and I still have family in the region. My family’s roots there stretch back centuries, on my mother’s side to the 1760s when refugees escaping the Acadian Deportation settled in the Baie des Chaleurs, and on my father’s side to the late 18th century when the fishing industry dominated by men like Charles Robin implanted itself in the region.

It should definitely be on your bucket list — especially if you like road trips. Route 132 around the peninsula is right up there with the Cabot Trail and the Sea-to-Sky Highway for epic drives in Canada. There’s the iconic Percé Rock, of course, but the real joy of the region is in enjoying the great outdoors, its small villages and the slower, quieter pace of life.

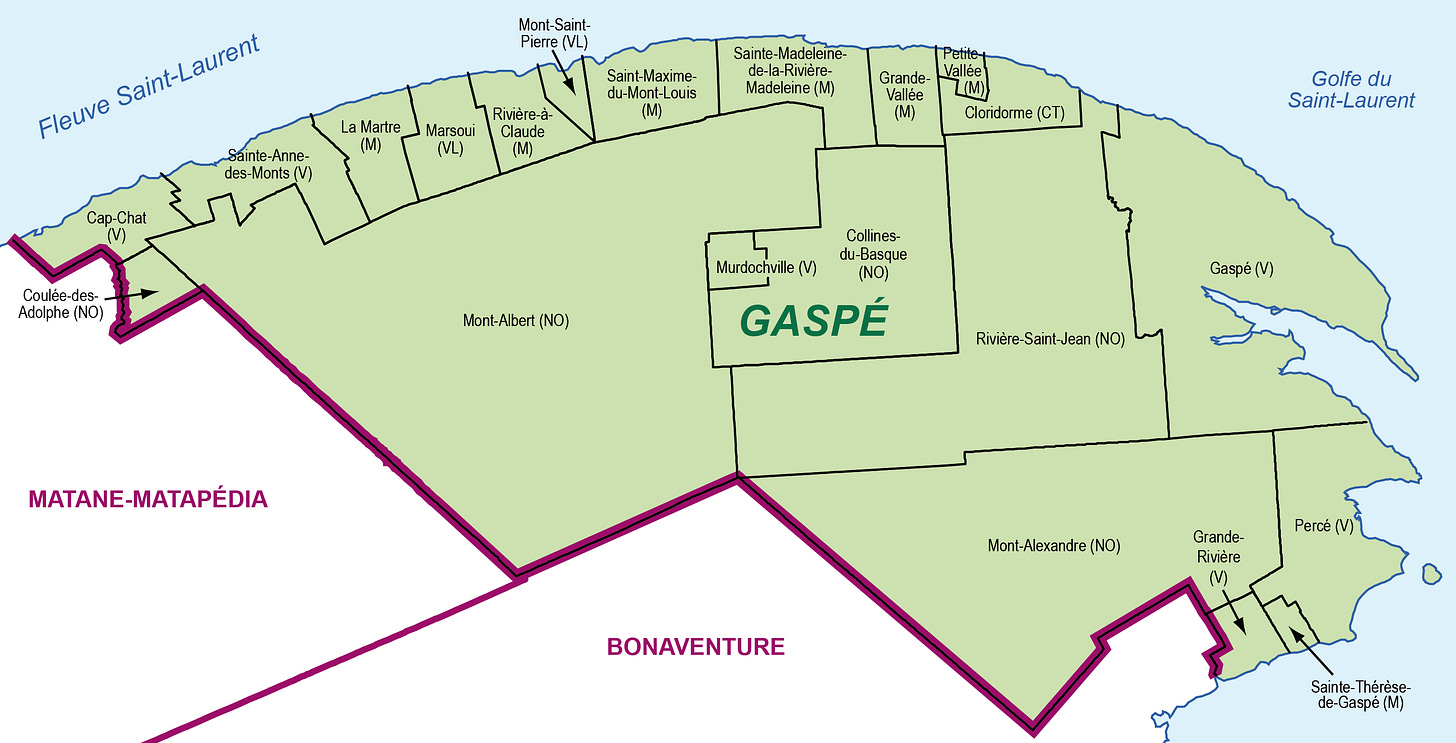

Located in the far east of the province north of New Brunswick, the riding of Gaspé is one of the two ridings that make up the Gaspé Peninsula, the other being the riding of Bonaventure. Of the two, Gaspé is setting up to be the more interesting contest in October as the Parti Québécois fights for survival.

In the 2018 election, the PQ narrowly held on to the seat it had won away from the Quebec Liberals in 2012. Méganne Perry Mélançon took 33.4% of the vote, beating out Alexandre Boulay of the Liberals, who took 33.2%. The CAQ’s candidate took 19.6%, while Québec Solidaire finished fourth with 13.8%.

The results were highly localized — the CAQ was far more competitive around Sainte-Anne-des-Monts while the Liberals won a lot of the polls north and south of the town of Gaspé, where there are pockets of anglophone residents, along with other villages along the north coast. The PQ was strongest in the east of the riding, winning polls primarily in the towns of Gaspé, Grande-Rivière, Sainte-Thérèse and in Rivière-au-Renard.

In the end, only 41 votes separated Perry Mélançon and Boulay, a result so close that a recount overturned the election night results that had Boulay narrowly ahead when one polling division recorded not a single vote for anyone but the Liberal candidate. An investigation subsequently concluded an error in how the count was recorded rather than anything nefarious.

But with both the PQ and the Liberals struggling in the polls, it’s an open question whether Gaspé will be a PQ-Liberal fight again. The PQ will certainly be fighting to hold the seat, but the Liberals’ collapse in support among francophones will make it harder for the party to be competitive in Gaspé, where only 6% of the population is anglophone.

Instead, the PQ might have to hold off the CAQ in Gaspé. Though the party was just below 20% last time, it isn’t hard to imagine the CAQ getting itself up around 30% in this riding, which would put it at risk for the PQ if their vote doesn’t hold up. That’s exactly the scenario our friend Philippe J. Fournier is envisioning in his model.

At the moment, neither the CAQ nor the Liberals have a candidate yet nominated for the riding. Despite its history in the region (and the fact the federal Liberals hold the seat), the Quebec Liberals are a long shot here. But whoever gets the CAQ nomination will likely be Perry Mélançon’s major opponent, if not the favourite to replace her.

(ALMOST) ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

A job looking for a man

July 7, 1938

Poor Robert Manion.

The Conservatives, through their various iterations, have had a number of leaders who never became prime minister. The last few might one day be forgotten, but that hasn’t happened just yet. Robert Stanfield has an airport named after him and John Bracken, in addition to being premier of Manitoba for decades, was responsible for bolting the word “Progressive” to “Conservative”, a legacy that still echoes in premiers’ offices from Winnipeg to Halifax.

But Robert Manion? If any past Conservative leader elicits a shrug, it’s him.

Manion’s rise to the leadership of the Conservative Party (known as the National Conservative Party at the time) occurred in 1938 in the shadow of another looming world war and that of an outgoing giant in the party.

R.B. Bennett had led the Conservatives since 1927, leading them to victory in 1930 and having the misfortune of governing Canada through the toughest days of the Great Depression. Accordingly, Bennett’s government was defeated in 1935 and, by 1938, it was time for Bennett to step aside and retire to an estate in England.

The Conservatives held their convention between July 5 and 7, 1938 in Ottawa. It would feature a few final speeches by Bennett, who was still seriously considering staying on as leader. Former Ontario premier Howard Ferguson was one of the big proponents for a Bennett comeback, but it was only when former prime minister Arthur Meighen, who also speechified at the convention, talked him out of it that Bennett finally admitted his political career was over.

“To have declared myself a candidate to succeed myself, at the eleventh hour,” he wrote in a letter after the convention, “would have been rather dishonourable.”

It would have been unfair to those candidates who had declared themselves under the assumption that R.B. was leaving. First among these, and the odds-on favourite to win, was Robert Manion.

A physician, Irish Roman Catholic and MP for the northern Ontario riding of Fort William until his defeat in 1935, Manion had been a cabinet minister in both Meighen’s and Bennett’s governments and had finished fourth in the 1927 convention. A veteran of the First World War who was liked within the party, the “white-haired, clean-cut” Manion had his biggest support base in Quebec. He was a Roman Catholic married to a French Canadian, qualities that promised success for Conservatives in Quebec and discomfort for elements within the party that weren’t too friendly to Roman Catholics or French Canadians, particularly when it came to their questionable attachment to the British Empire.

Among those opposed to Manion was Meighen, who still held influence within the party. Meighen was instead backing Murdoch MacPherson of Saskatchewan.

MacPherson, “a youngish man of force and vigour from the Prairies”, had been a cabinet minister in Saskatchewan’s one-term Conservative government. He was seen as a serious underdog until he gave a good speech at the convention, catapulting himself into contention.

Also backing MacPherson was John Diefenbaker, then the leader of the seatless Saskatchewan Conservative Party. Diefenbaker would eventually have designs on the national leadership himself, but for now he was complaining about the national party’s lack of support for his recent provincial campaign, guilting the chairman of the convention to send him $125 to cover his travel expenses to Ottawa. Diefenbaker also talked a Regina supporter into paying for his railway tickets for him and his wife, something Diefenbaker declined to mention when he accepted the $125.

In addition to Manion and MacPherson, there were three other candidates, all Toronto-area MPs: Joe Harris, Earl Lawson and Denton Massey. They were considered long-shots and fell out of contention as soon as MacPherson had taken the stage.

It was a tumultuous convention, as the Quebec delegates (flush with victory after Maurice Duplessis’s win in 1936) challenged the party’s position on defense that put it lockstep behind the British. There were also divisions between the left and right wings of the party.

“God help you because of the reaction of this party,” said W.D. Herridge on stage, after he was booed and heckled for putting forward progressive economic policies that the convention rejected. He warned that without adopting this approach, “the pages of history will record this as the day of [the party’s] funeral.”

When the voting was finally held, Bennett, Meighen and Ferguson were nowhere to be seen. Douglas R. Oliver of The Globe and Mail put it thusly: “the big guns which boomed in convention and outside convention, yesterday, and the day before that, and the day before that, but never a boom today.”

Though MacPherson had tightened the betting odds, on the first ballot it was Manion who emerged as the eventual choice of the party. He had 726 votes, just 60 short of what was needed for an outright victory. MacPherson trailed with 475 and the three southern Ontarians were further back.

Lawson was eliminated and threw his weight behind MacPherson. Neither Harris nor Massey stepped aside, but the bulk of their delegates went elsewhere. MacPherson gained the most votes on the second ballot, pushing his share up 173 votes to 648, but Manion earned enough new support (104) to win with 830.

He had been the favourite all along, even if no one seemed all that excited about the prospect. Oliver called the convention “the tale of a job that went looking for a man”, and the Conservatives had their man in Manion.

Manion had no seat in the House of Commons, but would contest and win a byelection in November 1938. He would eventually lead the Conservatives into the wartime 1940 federal election, pitching himself and his party as a National Government to mimic Robert Borden’s Union Government that had attracted Manion to the party in the first place.

It didn’t work. The Conservatives did no better than the trouncing they had received in 1935. Manion went down to personal defeat in his riding. Mackenzie King won the greatest victory he would as prime minister. By the next election, the war was (all but) over, Manion was dead and the National Conservatives had become the Progressive Conservatives. Not until 1957 and the leadership of John Diefenbaker, his $125 long spent, would the party be back in power.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Writ Podcast will be dropping on Friday. As always, the episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. And don’t forget to subscribe to my YouTube Channel, where I post videos, livestreams and interviews from the podcast!

Had MacPHERSON won Diefs future ambitions may have had a tougher ride to the leadership if MacPHERSON was around a while. One SASK leader a century!

I was going to grumble over Robert Manion's death getting such short shrift, but I gather that even his death was rather unremarkable: "On July 2, 1943, after taking a stroll through his neighbourhood, he came home and began reading in his library. He then informed his wife Yvonne that he was not feeling well. Within moments, he had collapsed and died." (https://canadaehx.com/2021/06/18/dr-robert-manion/)