The PPC: A blip or a beginning?

Gauging the People's Party's impact on the 2021 election

When the 2021 federal election campaign kicked off, the People’s Party looked about as irrelevant as it did in 2019, when Maxime Bernier’s new party captured just 1.6% of the vote.

The polls were awarding the party just 3% support, not much different from the previous election when the last polls of the campaign pegged the PPC at 2% or 3%. The Leaders’ Debates Commission decided the PPC didn’t meet their criteria of polling at or above 4% to qualify for participation — and rightly so.

But the PPC’s subsequent rise came as a surprise to many, including me.

That rise was not as meteoric as some suggested, however. Finishing with 4.9% of ballots cast, the PPC did not come close to meeting the double-digit support that some pollsters awarded the party.

Why interactive voice response polls over-estimated PPC support so dramatically is a question for a different time. What impact this phantom support had on the narrative of the campaign is another question that will have to go unanswered for the time being.

The most important question, however, is what’s next for the People’s Party.

It’s undeniable that the moment we’re in was the main driver of the PPC’s rise. It’s supporters were motivated by their opposition to vaccine mandates, mask mandates and lockdowns. But that might not be an issue that is still a live one when the next election is held — so, is there a future for the PPC after the pandemic is over (or at least under control)?

The continued success of far-right parties in Europe and the influence that Donald Trump still wields over the U.S. Republican Party could act as models for the PPC to follow if it wants to stick around.

For now, however, the PPC looks like a one-issue party with an uncertain future — and one that did not necessarily have as much of an impact on the results of the 2021 election as it might have had.

What the PPC vote looked like

There is a lot of overlap in the Venn diagram showing the electoral base of the People’s Party and the Conservative Party.

The PPC’s support was strongest in Western Canada, particularly the rural parts of the country where the Conservatives have their strength.

According to the final Léger and Research Co. polls of the campaign, which were closest to the mark, the PPC had slightly more support among men (6.5%) than women (5.5%). (Both polls over-estimated PPC support by about a point.)

The polls suggested the PPC was also most popular among those between the ages of 18 and 34, while Léger also indicated that the PPC had more support among those without a university degree.

But the differences were not enormous — the PPC still had support among older and better educated Canadians, too.

And contrary to what one might expect, there was also little difference in PPC support when it came to race. According to Abacus Data, the PPC had 5% support among white Canadians, and 6% support among non-white Canadians.

What drove PPC voters to the polls

This might be due to the issue that most galvanized PPC support. Bernier talked about immigration in 2019, for instance. But the 2021 PPC campaign was dominated by its opposition to restrictive measures to fight COVID-19 — an issue that cut across ethnic lines.

According to Léger’s post-election poll, it was on social media and discussion groups that PPC voters followed the campaign. They were the least likely voters to say they watched TV newscasts and 32% said their main reason for voting for the PPC was because of the party’s opposition to mask and vaccine mandates. Another 27% said it was because the party best represented their values and beliefs.

Just 20% of PPC voters said they were motivated by their disappointment with the Conservative campaign or Erin O’Toole in particular, suggesting that it wasn’t the Conservatives’ move to the centre that pushed a lot of their voters over to the PPC.

And the thing that sparked the PPC’s creation in the first place? Just 2% said they supported the PPC because of its libertarian politics.

How PPC vote broke down across the country

Prior to the election, guessing where were the PPC’s regional bases of support was difficult because of how poorly the PPC did in the 2019 election. When a party is scoring 1% to 3%, it is hard to discern many patterns from that.

But some regional patterns in the PPC’s support are much easier to figure out now.

In Atlantic Canada, the PPC did best in New Brunswick. The Conservatives do better in New Brunswick than in the rest of the region, and there is also the influence of the provincial People’s Alliance of New Brunswick.

The PANB is a populist party with seats in the provincial legislature. It also uses the same shade of purple as the PPC, even if it is far more moderate than the PPC. Nevertheless, that might have made the PPC seem like a more legitimate option for many voters in the province. The PANB had over 12% of the vote in ridings where it ran candidates in the 2020 New Brunswick election.

The PPC also did well in the Halifax area, but that is due to the lack of a Conservative candidate in Dartmouth–Cole Harbour (the only seat in the country where the Conservatives didn’t have someone on the ballot). The PPC earned 10.5% of the vote in the riding, its best result in Atlantic Canada. Undoubtedly, many of those votes were Conservatives who would have supported a Conservative candidate had there been one.

With that exception, the PPC did not get very strong results outside of New Brunswick, especially in rural areas where they did well in other parts of Canada. The PC-strain of conservatism in Atlantic Canada might be a resistant one.

Next door in his home province, Maxime Bernier is even less popular.

Unlike in most parts of the country, the PPC only enjoyed modest increases in support across Quebec. They actually dropped in the Quebec City Region (which, in my regional grouping, includes Beauce) and were unpopular in other areas where the Conservatives score well.

The PPC is just not breaking through in Quebec. (The presence of the somewhat bizarre Parti libre in Quebec might have compounded the PPC’s difficulties.)

Bernier might want to consider running somewhere else next time. He lost his riding of Beauce by 30 points, with his support dropping about 10 points from his performance in 2019. There’s no reason to expect he can win in Beauce as a PPCer.

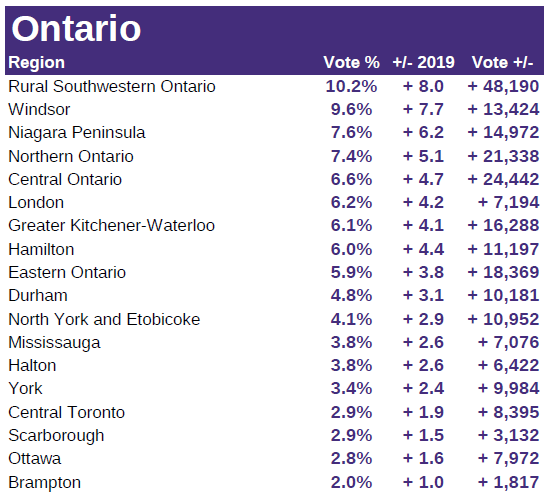

Southwestern Ontario might be a better option. The PPC scored 10.2% in the rural parts of the region, its best performance east of Manitoba.

In addition to the rural areas of southwestern Ontario, the PPC also had strong results in the three Windsor-Essex ridings, perhaps due to the working class population and its exposure to U.S. media. It is an outlier though, as Windsor was a lone urban area among the the PPC’s top-performing regions.

The PPC also had decent results in the southwestern cities of London and in the Greater Kitchener-Waterloo area, as well as in Hamilton and on the Niagara Peninsula.

The party didn’t have much appeal in and around Toronto, however. With less than 4% of the vote outside of Durham, North York and Etobicoke, the PPC really wasn’t much of a vote-splitter in the Greater Toronto Area.

But the PPC cleared double-digits in both rural Manitoba and rural Alberta, and came close to doing the same in rural Saskatchewan. The PPC had less appeal in urban centres in Western Canada, however, with only 4-5% in Saskatoon, Calgary, Winnipeg and Regina, and 6.5% in Edmonton. Still, that was more than the PPC managed in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver or Ottawa.

Six of the PPC’s seven second-place finishes were in the Prairies, while Manitoba had two of the PPC’s best three results: 21.6% in Portage–Lisgar and 16.5% in Provencher. (Beauce was the other second-place finish and top result.)

In British Columbia, the pattern continued of the PPC putting up its best numbers in areas where the Conservatives are strongest: the B.C. Interior ad the Fraser Valley. But the closer one got to Vancouver, the lower the PPC’s support. The jump of less than two points for the PPC in and around that city was among the lowest in the country.

PPC likely cost Conservatives few seats

There was a lot of discussion about just how much of a problem the PPC would be for the Conservatives. It’s certainly true that as the Conservative vote inched down in the last stages of the campaign, the PPC’s vote inched up. But it is hard to identify many ridings where the PPC undoubtedly cost the Conservatives a win.

Take a look at the Conservatives’ vote share in the regions where the PPC did best:

With the exception of Windsor and the Niagara Peninsula, the Conservatives were dominant in all the regions with the highest PPC support and biggest increases since 2019. It means that the PPC’s surges only reduced the Conservatives’ margins of victory in most of these ridings.

In rural Western Canada, there does seem to have been a clear movement from the Conservatives to the PPC, as the vote for the Liberals and NDP hardly budged.

It’s not as clear what happened in southwestern Ontario, Windsor or the Niagara Peninsula, where the Conservative vote held. Did the PPC draw support from the Greens in these regions? Did it get new voters to come out to replace other voters who stayed home? Did the Conservatives gain voters from the other parties but lose some of their base to the PPC? Any of these could be true. A combination likely is.

But did the PPC cost Erin O’Toole the prime minister’s office? I don’t think so.

There were 22 seats across the country in which the PPC vote was bigger than the Conservatives’ margin of defeat. These were particularly concentrated in northern and southwestern Ontario and in British Columbia.

Had all 22 of those seats gone to the Conservatives, O’Toole would have emerged with 141 seats in total, against 144 for the Liberals, 31 for the Bloc Québécois, 19 for the New Democrats and two for the Greens.

But it is extremely unlikely that every vote for the PPC was a vote that would have otherwise gone to the Conservatives.

The Léger exit poll suggested only 20% of PPC voters were primarily motivated by their dissatisfaction with the Conservative option. And polls during the campaign suggested the chunk of the PPC vote that had supported the Conservatives in 2019 was nowhere near 100%, and instead more in the 25% to 50% range.

In only seven seats was 50% of the PPC vote still greater than the Conservatives’ margin of defeat. At the 25% mark, we’re only talking about three seats.

Those three seats were Trois-Rivières in Quebec (because the Conservatives were so close, not because the PPC was so high) and Sault Ste. Marie and Kitchener–Conestoga in Ontario. At the 50% mark, the extra four seats are Edmonton Centre, Nanaimo–Ladysmith, Kitchener South–Hespeler and Niagara Centre.

Beyond these seven, an increasingly implausible share of the PPC vote needs to go to the Conservatives to win them the seat. Yes, the PPC probably cost the Conservatives a few seats. Maybe even a dozen if we’re being very generous.

But the PPC didn’t cost the Conservatives the election.

What’s the future for the PPC?

That brings us to what’s next for the PPC. After 2019, the party looked like a failed Bernier vanity project. In 2021, it took more of the vote than the Green Party has in all but two elections.

The Greens, however, were able to concentrate their support in a handful of areas to win seats. It’ll be harder for the PPC to do that.

The People’s Party cleared 10% in 25 ridings, but 15% in only three. In no seat did they finish within 21 percentage points of the winner, and only three in which they were within 25 points.

It won’t be easy to overturn a 20+ point margin for a party with limited appeal beyond a small minority of the population — particularly when the No. 1 issue for the PPC is vaccine mandates or lockdowns. Only a tiny portion of the adult population isn’t vaccinated or opposes these measures.

Does this mean the PPC will fade away as the pandemic becomes less of a daily concern and the number of unvaccinated Canadians gets smaller and smaller?

There’s definitely a link between the PPC and vaccination rates. The parts of Ontario with the lowest vaccination rates are almost all in the southwest and the north, where the PPC vote was higher. The three provinces with the lowest vaccination rates — Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba — are the three provinces where the PPC did best. Parts of Portage–Lisgar, the PPC’s best riding, have among the lowest vaccination rates in the country.

So, it’s possible the PPC will prove a pandemic blip.

But it could also emerge as the standard bearer of the far-right’s grievance-du-jour, taking on the role of far-right parties in Europe that routinely earn a large share of the vote. In 2021, it was vaccine mandates. In 2025, it could be immigration, or multiculturalism, or “elites”, etc.

Is Maxime Bernier the man to lead such a party? His main issue was once supply management. He is now a long way from worrying most about the cost of eggs, milk and cheese.

But if he can continue to adapt with the changing mood of the angriest chunk of the electorate, the PPC could be here to stay.

Other election analyses in the series:

Interesting insight and potentially useful input to the coming CPC leadership race.