Poilievre wins big — everywhere

Landslide victory hands Pierre Poilievre 330 of 338 ridings

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II was a dominant theme of the Conservative leadership event on Saturday, from the sombre music that greeted attendees as if they were arriving to a funeral, to the performance of God Save the King and eulogies to the late monarch uttered by virtually every speaker who took the stage.

Perhaps, then, it is fitting that what those Conservatives who gathered at the Shaw Centre in Ottawa witnessed was a coronation.

Pierre Poilievre won the Conservative leadership with a landslide first ballot victory, far surpassing the eked-out wins by his predecessors, Andrew Scheer and Erin O’Toole, or the first ballot result Stephen Harper secured when the party held its first leadership race in 2004.

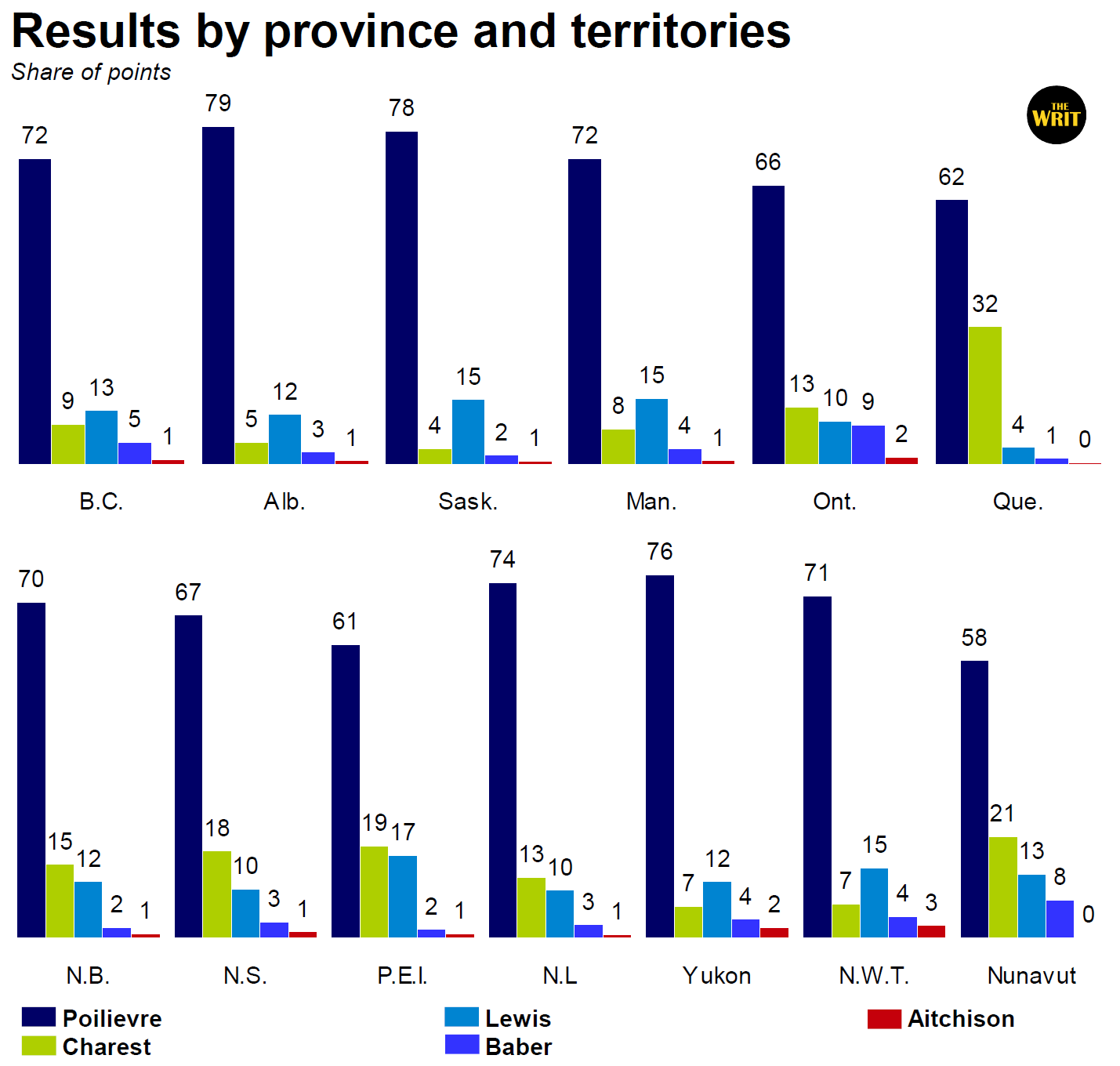

Poilievre took 68.2% of the points, beating his nearest rival by a country mile. Jean Charest captured 16.1% of the points, followed by Leslyn Lewis at 9.7%, Roman Baber at 5% and Scott Aitchison at 1.1%.

The Ontario MP won a majority of points in all 13 provinces and territories and the plurality in every riding in all but Ontario and Quebec, where Charest won two and six ridings, respectively. That gave Poilievre a staggering 330 to eight victory margin.

In terms of actual votes cast (some 418,000 in all), Poilievre won 70.7%. Charest barely placed second with 11.6%, followed by Lewis at 11.1%, Baber at 5.4% and Aitchison at 1.2%.

Charest’s campaign claimed that they could win based on the points system. They were right that their candidate was going to be the beneficiary of the system that gave every riding equal weight. It boosted his scored by 4.5 percentage points and penalized Poilievre by 2.5 points. But that net effect of seven percentage points meant little when the popular vote margin was 59 percentage points.

At the provincial and territorial level, only in Nunavut did Poilievre fail to clear the bar of 60% and he had over 70% support throughout Western Canada, as well as in Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and the two other territories.

As expected, Poilievre absolutely dominated Western Canada. He took 71.9% of the points in British Columbia, 79.4% in Alberta, 78.3% in Saskatchewan and 71.9% in Manitoba. In all four provinces, Lewis placed second with scores ranging from 11.7% in Alberta to 15.4% in Manitoba. Charest was third throughout the region, failing to hit double-digits. British Columbia, with 9.4%, was his best province west of Ontario.

Ontario wasn’t much more competitive, with Poilievre taking 65.6% of the points and Charest finishing with just 13.4%. Lewis was third with 10.1%, followed closely by Baber at 9.2%. Aitchison managed just 1.7% in his home province, though that was his best result outside of the North.

The impact of Patrick Brown’s campaign appears to have been minimal. Poilievre captured 71.1% of the points in Brampton’s five ridings, while Charest had just 15.6%. And there wasn’t an influx of members in Mayor Brown’s town — there were nearly half again as many voting members in, say, Niagara’s three ridings as there were in Brampton’s five.

Charest did best in Quebec, but he didn’t win the province. It wasn’t even particularly close. The former Quebec premier had 32.3% in Quebec, putting him well behind Poilievre’s 62.2%. Lewis was third with 3.9%, Baber had 1.3% and Aitchison took just 0.3%.

While that was one of the lower results for Poilievre across the country, he still won Quebec on the first ballot with more of the vote than O’Toole did on the third ballot in 2020 or Maxime Bernier did on the 13th ballot in 2017.

Six of the eight ridings Charest won were in Quebec (two were Conservative-held ridings). They were spread out across the province, with three in the Greater Montreal region, one in Quebec City, one in the Saguenay region and the last being his former riding of Sherbrooke. But he didn’t win any of these decisively — he won them all with less than 60% of ballots cast. He only squeaked by in Sherbrooke with 51%.

In Ontario, Charest’s two riding wins were in Ottawa Centre and Toronto’s University–Rosedale, perhaps two of the most political-establishment-ish ridings one could imagine in Canada.

Finally, in Atlantic Canada the old Red Tory wing of the party appears to have been broken, as Poilievre managed 61.3% in P.E.I., 67.4% in Nova Scotia, 70.1% in New Brunswick and 74.2% in Newfoundland and Labrador. Charest was second in all four provinces — his 18.1% in Nova Scotia and 19.1% in P.E.I. were his best results outside of Quebec and Nunavut — but Lewis scored her best result in P.E.I. with 17.2%. She also managed double-digits in the rest of the Maritimes.

It’s an emphatic victory for Poilievre with few signs of regional weaknesses. In 2004, Harper failed to win Quebec and Atlantic Canada. In 2017, Scheer was second in Quebec and Alberta. In 2020, O’Toole was beaten in the Maritimes.

But in 2022, Poilievre won everywhere.

It might make the few caucus members who didn’t endorse him a little nervous. Not only do they find themselves on the losing side, but nearly all of them couldn’t deliver their own ridings. Lewis didn’t win a single riding and averaged just 18.5% of the vote in the 10 ridings where she had MP endorsements.

Only one MP who didn’t endorse Poilievre, Richard Martel in Chicoutimi–Le Fjord, delivered his seat. Charest managed 51% of the vote in this riding. His other 15 caucus endorsers failed to deliver their seats and Charest finished in third place in seven of them. He averaged just 22% in the 16 ridings in which he had an MP endorsement — and 9% in those outside of Quebec.

Those results are embarrassing for Charest and the old PC wing of the party. They have shown themselves to be an increasingly minor force within the Conservative Party for the fourth consecutive leadership contest. At this point, they either have to give up or start anew.

It’s also a bad result for Lewis and the social conservative wing. The votes of Brad Trost and Pierre Lemieux in 2017 were essential in Scheer’s defeat of Bernier. The votes of Lewis and Derek Sloan were key for O’Toole to defeat Peter MacKay in 2020. But in 2022, the social conservative wing didn’t get to play the kingmaker role again. A lot of them might have supported Poilievre, but he owes them far less than Scheer or O’Toole ever did.

At the personal level, Lewis’s standing looks diminished. On the first ballot in 2020, she had 43,000 votes and 20.5% of the points. On the first ballot in 2022, she had 46,000 votes and just 9.7% of the points. In a contest that saw turnout jump by about 244,000 votes, Lewis was responsible for only about 1% of that growth.

It means Poilievre has complete dominion over the party. The membership is behind him, as is a majority of caucus members. His main ideological rival, Charest, was humiliated. One of the big interest groups in the party, social conservatives, have been relegated to the sidelines. Poilievre’s populist, anti-elite style — the crowd chanted “freedom!” when the results were announced — is the party’s identity now.

Surely this was the easy part: recognizing that the party has moved to Canada's version of the far right and pitching his appeal accordingly. Poilievre still has to rebuild the party's policy platform from the ground up, while being cognizant of the need to appeal outside his angry base, prevent progressive conservatives from leaving and keep the hungry tiger he's now riding from devouring him. Nothing in the bigger electoral picture has changed since O'Toole; how will Poilievre pull off what O'Toole couldn't to move on to win government?

Thank you for this , Eric. I listened on the car radio to the acceptance speech. PP is not my guy, nor is the CPC, but it was a powerful, logical, carefully conceived presentation. Several specific policy highlights do make sense and will have appeal - housing esp for 30 somethings, use of public lands, and use of domestic vs “ dictator “ oil . Look out Justin , and the NDP (who will lose voters to both CPC and to Liberals to ward off scary PP).