If Jean Charest has a path, he'll have to build it

The road ahead for Charest won't be a fairly easy one.

Can Jean Charest win the Conservative Party leadership? Yes — in theory, Charest is a serious contender.

In theory.

If you listened to The Writ Podcast last week, you heard Chad Rogers giving Charest some pretty long odds. Now, I don’t think Charest’s chances are necessarily as slim as that. He definitely has a path to victory — if he builds it. The party base as it currently stands would not have him, so he has to construct himself a new base.

Let’s break down the pros and cons of Charest’s candidacy.

Pros: Charest was once a heavyweight

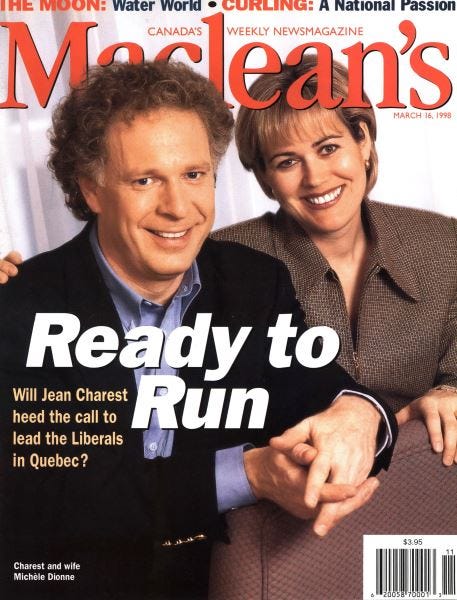

Charest has been involved in politics for about as long as I have been alive. He made his mark right from the start as the youngest cabinet minister in Canadian history in Brian Mulroney’s first PC government.

He went on to contest the 1993 Progressive Conservative leadership, losing it to Kim Campbell. But as one of two surviving PC MPs after that catastrophic election, Charest emerged as Campbell’s successor, played an important role in the 1995 Quebec referendum and led the PCs to a respectable showing in the 1997 federal election.

Then he made the jump to provincial politics. He lost the 1998 Quebec election to Lucien Bouchard’s Parti Québécois, but his Quebec Liberals won more votes, sapping any momentum Bouchard was hoping to build for a third referendum. Charest won the next election in 2003, was re-elected in 2007 and 2008, and served as Quebec’s premier until his defeat in 2012.

So, Charest has instant name recognition that most candidates would love to have. And many Canadians have fond memories of Charest due to his involvement in keeping the country together in the 1990s.

These days, he is running on a platform of being able to defeat Justin Trudeau and form a national Conservative government. His politics would put him in the mushy middle where elections are won and he is flawlessly bilingual. He’s a known quantity as a good campaigner and has plenty of election wins under his belt, so he has some proof points to back up his claim.

Hoping to build a serious, mature party, Charest could bring lapsed Conservatives back into the fold, a pool that might be untapped. There could be plenty of members there that a candidate like Pierre Poilievre cannot hope to recruit.

Charest has the potential to have lots of appeal in Quebec and a robust organizational structure that can deliver the province to him. Atlantic Canada, with its Red Toryism (and Charest PC support back in 1997), could also be a region of strength.

If you’re a Conservative (or potential Conservative) whose No. 1 priority is to defeat Trudeau, Charest just might be your man.

Cons: Charest was once a heavyweight

Or, he might be yesterday’s man.

Charest hasn’t been active in politics for a decade, hasn’t won an election since 2008 and his experience of federal politics was a quarter century ago. At 63 years old he still has lots to give — B.C. Premier John Horgan is only one year younger, Quebec Premier François Legault is one year older, New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs is 68 — but his years in office mean he has accumulated a lot of baggage.

A record can be a good thing, but it can also weigh you down. We’ve already seen how Poilievre is using Charest’s record (on taxes and the gun registry, for instance) against him. The stories of corruption surrounding Quebec politics during Charest’s tenure have also left a mark.

And, being a past provincial premier has not exactly been a ticket to the prime minister’s office:

His time as the leader of the Quebec Liberal Party make it easier to paint him as not-a-Conservative, despite the PLQ’s history as a federalist coalition largely in the centre of Quebec’s politics and whose affiliations with the federal Liberals were broken in the 1950s.

Quebec Liberals have become respected federal Conservatives before — think of Lawrence Cannon or Claude Wagner — but Charest’s time with the red team is a weak spot.

As someone pitching tact and experience (to paraphrase the statement on his website), Charest might be at a disadvantage in inspiring people to sign-up in support of him. He doesn’t have the energy that Poilievre’s style of grievance politics brings to the table.

And Charest’s most important plank in winning the leadership — Quebec — might be wobbly.

The cons seem to outweigh the pros for Charest. But he can still win it. Here’s how.

Charest needs to do (much) better than MacKay

To find Charest’s path, let’s go back to the 2020 leadership race and use that as our guide.

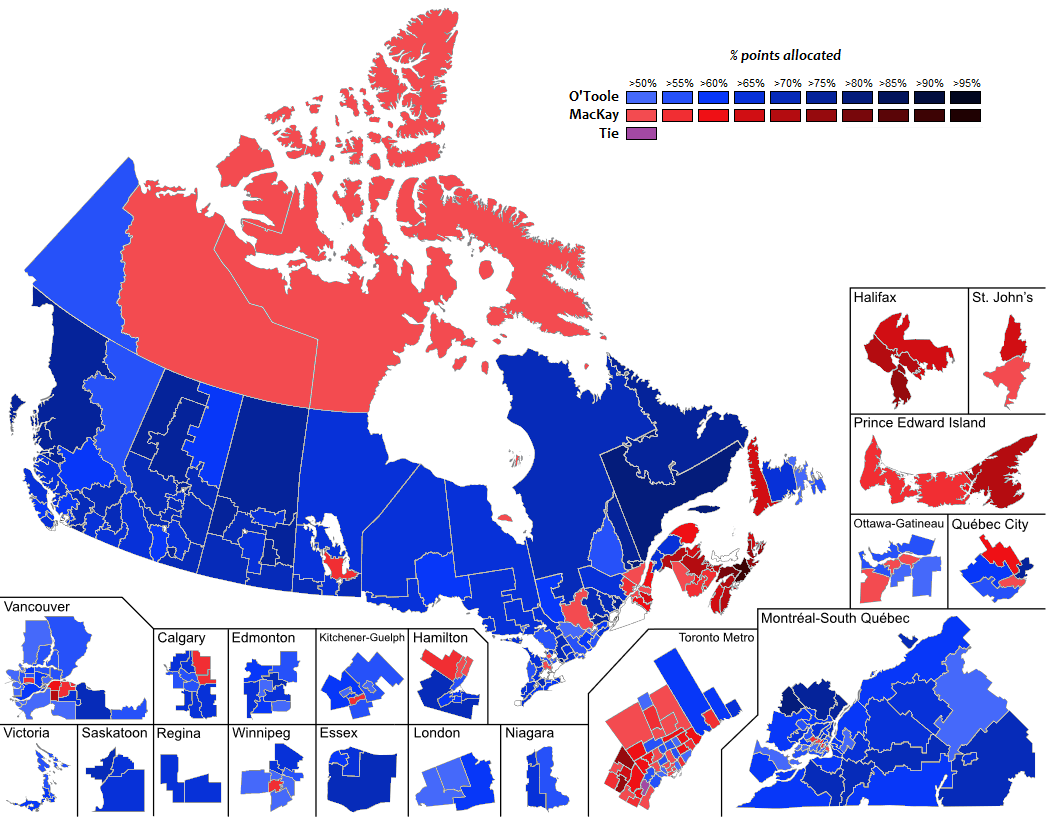

We’ll start with the assumption that Erin O’Toole’s results on the third and final ballot will be the equivalent of what Poilievre will do on a final ballot this time. This is a plausible starting point, as Poilievre is running (and perhaps more authentically) as what O’Toole portrayed himself to be in 2020: a True Blue Conservative.

Born and raised in Alberta, a defender of the oil and gas sector and a thorn in the side of Liberals, Poilievre is unlikely to do worse than O’Toole did in Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2020. O’Toole managed 66% of the points in Alberta and 72% in Saskatchewan.

Charest will need to overcome that Western Canada deficit, along with the support Poilievre is likely to get in the rural parts of Canada.

Can Charest be 2022’s Peter MacKay? Well, he has the same PC heritage. Charest will need to replicate MacKay’s dominance in Atlantic Canada, as well as his good results in and around Toronto.

If he does that, he’d still be about 2,400 points short of the 16,900 needed to win.

Key will be Quebec. MacKay lost the province to O’Toole by a significant margin of 61% to 39%. If Charest doesn’t do better than that, he’s doomed. At a minimum, he would need to flip those numbers in his favour, winning about 60% of the vote in Quebec and so gaining roughly 1,600 points.

Where can he find the remaining 800 points needed to win? It is hard to imagine Charest can beat MacKay’s performance in Atlantic Canada, so he’ll have to look elsewhere.

Toronto would be a start. If Charest can sweep the urban membership in Toronto — which MacKay did not do — and do better in places like Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver, he can get to 16,900 points.

Winning those urban centres could be helped by a strong showing from Patrick Brown, with his voters ranking Charest second.

There is a complication there, though, in Bill 21. While Charest has come out to say he opposes Bill 21 and would intervene if it gets to the Supreme Court, he will likely be pressed on this issue and will be wary to speak out as strongly against it as Brown has, lest he reduce his chances of winning Quebec.

If this becomes an issue for Charest, that could limit his potential in places like Brampton, Mississauga, Calgary and Surrey, limiting his paths to victory.

Again, this all hinges on dominating in Quebec. But that’s not a given. O’Toole won Quebec by recruiting members motivated by the issue of gun control. Charest’s aim will have to be to swamp those single-issue members with new recruits.

How many will he need? Well, MacKay was 27,000 raw votes behind O’Toole, so the Charest camp will need to recruit at least that many to have a hope. And, considering that not every MacKay vote will go Charest’s way, he will likely need much more than that — perhaps 50,000 or 75,000 to be a serious contender.

An alternative path for Charest would be to wind up on the final ballot with Leslyn Lewis, something that is out of his control. But if he were to be up against Lewis, his chances would improve. He’d run up the numbers in Quebec against the unilingual Lewis, beat MacKay’s scores in Red Tory Atlantic Canada, and perhaps attract enough centrist Poilievre voters to secure his victory.

But a Lewis-Charest final probably means an imploding Poilievre campaign — and there’s no sign of that happening.

Is Charest built to win?

Put aside, for the moment, Charest’s chances of winning the Conservative leadership. Let’s focus on his chances of winning a general election, especially since his main campaign pitch seems to be largely predicated on his ability to beat Justin Trudeau.

But it’s not clear that Charest has a much better chance of doing that than Poilievre.

A recent Léger poll found that, among all Canadians, Poilievre was seen as the best person to lead the party by 15% against 12% for Charest. If Charest was better for the general electorate, one would expect him to be ahead here.

(The 10% score for MacKay and 2% for Tasha Kheiriddin in this poll complicates matters, as Kheiriddin and MacKay are out, and Charest would probably get a good chunk of that combined 12%).

Léger also found that voting intentions would not improve under Charest. With him as leader, the Conservatives were five points back of the Liberals at 28%. With Poilievre, they were four points back at 30%.

The wild card appears to be the People’s Party, which goes from 7% with Charest as Conservative leader to just 3% with Poilievre at the helm. Poilievre blunts the PPC’s appeal — though what he might have to do to keep that appeal could, in the long run, lessen his ability to grow.

And the question of whether Charest can deliver Quebec to the Conservatives is an open one. According to Abacus Data, only 8% of Quebecers have a positive impression of Poilievre, compared to 20% for Charest. But 47% have a negative impression of Charest, compared to 24% for Poilievre. Charest comes with more upside, perhaps, but also lots of downside.

Indeed, when Léger asked Quebecers in 2020 to reflect on their past leaders, Charest did very, very poorly. Only 24% reported having a good opinion of the former premier, with 72% saying they had a bad opinion. (The lack of a “neutral” option, as in the Abacus poll, likely explains the difference.)

This could go sideways

So, there is a chance this does not go well for Charest.

He definitely has a path. It requires that Charest out-performs MacKay’s 2020 results, and Poilievre does not match O’Toole’s. It requires that Charest signs up a lot of members, that Brown does the same and that they go to Charest in big numbers.

Charest needs to do very well in Quebec, Atlantic Canada and big urban centres in the rest of the country.

The alternative, though, could be rough. It’s possible that Charest falls very flat in Western Canada, including in the big cities. Brown could beat him in Ontario and Charest could under-perform in Quebec. The result would then be that Brown finishes ahead of Charest, and Charest is eliminated before the count is over.

There’s even a plausible scenario in which Charest finishes fourth behind Poilievre, Brown and Lewis, who managed to registered 20.5% support on the first ballot in 2020 (despite the presence of Derek Sloan, another social conservative). It’s not unimaginable that Charest would fall short of that mark in a crowded field.

It would mark a rather ignominious end to a long, storied and successful political career for Jean Charest. I hope he knows what he’s doing.

Charest has what I would describe as a hall of mirrors to victory. He has to make every correct turn to find the prize at the end, and he has a lot of turns to make. If not he will get lost or end up back at the entrance.

I see Charest as being a Kamala Harris sort of candidate. Lot of establishment support; not much popular support. Hyped up by the meida; but will fall flat when he faces the electorate