#EveryElectionProject: Quebec

Capsules on Quebec's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Quebec.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1878 Quebec election

The ‘coup d’état’

May 1, 1878

The relationship between the premier and lieutenant-governor of Quebec was tense in 1878. On the one side there was Charles Boucher de Boucherville, the patrician Conservative premier. On the other there was Luc Letellier de Saint-Just, the Liberal lieutenant-governor who chafed at his — technically, at least — non-partisan role.

Letellier had been appointed to the post by Alexander Mackenzie, the Liberal prime minister in Ottawa, who was sorry to let go of one of his top ministers. The Conservatives in Quebec didn’t like Letellier and disrespected him at every opportunity, refusing invitations to Spencer Wood, his official residence, and printing proclamations under his name that he never signed.

But it was a mutual dislike. Letellier wasn’t above descending into the political fray and the Conservatives didn’t see him as the neutral representative of the Crown that he was supposed to be.

When the Conservatives brought forward legislation that would compel municipal governments to contribute to the cash-strapped provincial government’s railway building plan, Letellier decided he had seen enough. Citing this overreach, as well as the general mismanagement he saw in Boucherville’s government, he dismissed the premier, inviting him to name his successor. When Boucherville refused, Letellier asked the leader of the Quebec Liberals to form a government.

That put Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotibinière in a delicate position. No less patrician than Boucherville — they were both old-fashioned seigneurs — Joly didn’t have anything close to a majority in the Legislative Assembly. So, a dissolution was requested and the province went to the polls.

Joly promised to bring Quebec’s finances into order, ending the corrupt practices of the previous Conservative government. The Conservatives, with future premier Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau leading the charge on the hustings as the prime spokesperson, railed against Letellier’s undemocratic coup d’état: “silence the voice of Spencer Wood,” he intoned, “and let the mighty voice of the people speak.”

Even many Liberals were squeamish about what Letellier had done, including Prime Minister Mackenzie. “We have always as Liberals fought against this,” he told one of his ministers. “The elevation of our friends [in Quebec] with a wrong principle to defend would be a very doubtful advantage.”

Likely agreeing with Mackenzie, Joly and the Liberals made the campaign about the record of the Conservatives, who they deemed the “taxationists”. Friendly newspapers (which were all partisan at the time) tried to made the case to readers.

“The eventful hour approaches,” wrote the editorialists of Quebec City’s Morning Chronicle, “which must settle the contest between the ins and the outs; between Mr. Joly and Mr. DeBoucherville; between the friends of retrenchment, economy and the honest administration of our public affairs, and the venal supporters of the late regime of dishonesty, reckless extravagance, taxation, illegality, pillage of the public chest and eventual bankruptcy.”

Perhaps sensing that the Conservatives had a weakness on this score, their friends tried to deflect. The campaign was not about the record of the government, claimed the Montreal Gazette, but about the outrageous actions of Letellier and the Liberals.

“We make a last call upon such of our Conservative friends … who may feel disposed to abstain, or to vote for the Joly Government in this election, to think better of such a resolution; and for two reasons,” argued the Gazette. “The first reason is that by so doing, they will be helping the Mackenzie Government … There is another reason. This election has nothing to do with Mr. DeBoucherville … The true and only issue of these elections is to endorse or disapprove of M. Letellier. Parliament decided that the people had to decide this constitutional question, and until was decided all other questions are in abeyance. Let our friends reflect on these simple truths, and we trust that not one of them will give his influence towards the infliction of Rouge-ism on this city and Province.”

The result showed a split down the middle in Quebec and one of the province’s closest elections ever. The Conservatives saw their seat haul cut by a quarter down to just 32 and their share of the vote drop by 1.5 points to 49.5%. The Liberals made significant gains, largely in and around Quebec City, jumping 12 seats to 31 and nearly nine percentage points to 47.5%.

But Joly did not win a plurality of seats — the Conservatives still had the most seats in the assembly and their newspapers cautiously proclaimed a narrow victory. Two Independents held the balance of power, and considering they were Independent Conservatives, presumably they would side with Boucherville.

They didn’t. The two Independents backed Joly and the Liberals formed what would be their first elected government in the history of the province. But a one-seat majority was no majority at all, and it wouldn’t be long before Joly lost the confidence of the legislature in late 1879. When that happened, the lieutenant-governor did not hesitate to ask Chapleau to form a government rather than go back to the polls and there was no scandal — because that lieutenant-governor was no longer Letellier. It was former Conservative MP Théodore Robitaille who instead had the good fortune of being named Letellier’s replacement shortly after John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives were calling the shots again in Ottawa.

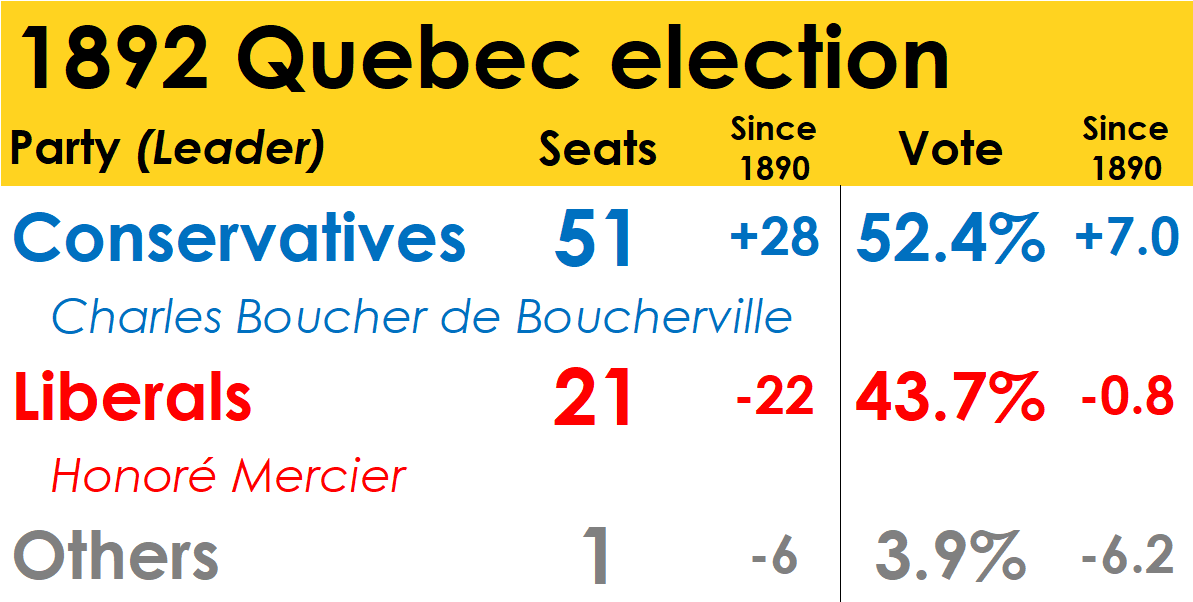

1892 Quebec election

Mercier shown the door

March 8, 1892

Here’s a question for you: who was Quebec’s first nationalist premier?

François Legault is only the latest iteration. Maybe you’re thinking it must be a premier from the Quiet Revolution — perhaps René Lévesque or Jean Lesage. Earlier than that? Could it be Maurice Duplessis, who combined Quebec nationalism with fervent Roman Catholicism?

Nope, you have to go back even further to the end of the 19th century to the days of Honoré Mercier.

In the 1880s, Quebec was in a state of nationalist effervescence. Not Québécois nationalism, though, as that didn’t quite exist yet, but French Canadian nationalism, with Quebec as the homeland of the country’s Catholic, French-speaking population, including everyone from Acadians in the Maritimes to the Métis in the west.

The execution of Louis Riel, who was adopted by French Canadians as one of their own (and Riel himself had complicated and shifting views about his own identity), in 1885 further fanned those flames of nationalism. Mercier, who had started the Parti national as a third way that was neither Liberal nor Conservative — though it ended up being subsumed into the Liberal Party — was able to capitalize on this and ride it to power in Quebec in 1887 as head of a coalition that included Conservatives who opposed John A. Macdonald’s decision to hang Riel.

Mercier was re-elected in 1890 and was greatly popular within Quebec and French-speaking circles outside the province for his muscular and populist French-Canadian nationalism. But his fall from grace was swift. In 1891, Mercier was taken down by scandal involving the construction of the Baie des Chaleurs Railway on the Gaspé Peninsula, when reports emerged that public money had been funneled through the local contractor back into Liberal coffers.

Mercier would eventually be personally exonerated, but the damage had been done. He was dismissed by the lieutenant-governor, who then called on the Conservatives to form a government — despite not holding a majority in the legislature.

Charles Boucher de Boucherville, who was sitting in the Senate in Ottawa at the time, was called upon to lead that Conservative government. While Mercier and the Liberals tried to raise a hue and cry about this undemocratic move, Boucherville took the title of premier in December 1891 and immediately asked the lieutenant-governor for a dissolution, calling for new elections to be held on March 8, 1892.

Boucherville, a legislator for more than 30 years stretching back to before Confederation, had previously served as Quebec premier from 1874 to 1878, during which time he modernized Quebec’s election laws by ending the practice of holding votes on different days and instituting the secret ballot. His time in office came to an end when he, too, was dismissed by the lieutenant-governor, but the Senate had proven a comfortable landing place.

The election went badly for Mercier and the Liberals and voters showed little concern about the interference of a partisan lieutenant-governor. The stench of political corruption was so strong that Wilfrid Laurier, the leader of the federal Liberal Party, kept himself out of the campaigning (with the exception of one visit to Quebec City nearly two months before voting day).

The result was a rejection of the once-popular Mercier, as his Liberals lost 22 seats and held onto only 21. Their share of the vote, at nearly 44%, held firm. But the Conservatives gained seven points and picked up 28 more seats, giving them a commanding majority with 51 in the Legislative Assembly.

Mercier resigned shortly after the election, denouncing the charges that had been laid against him. Félix-Gabriel Marchand, who as speaker during Mercier’s government had kept himself largely above the partisan fray, would take his place as Liberal leader.

But Boucherville’s second stint as premier also proved to be short. When Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, a long-time and hated rival in the Conservative Party, was appointed the new lieutenant-governor, Boucherville refused to serve under him and resigned before the end of 1892.

It’s a reminder of just how long it has been since anyone cared that much about who was the lieutenant-governor of Quebec.

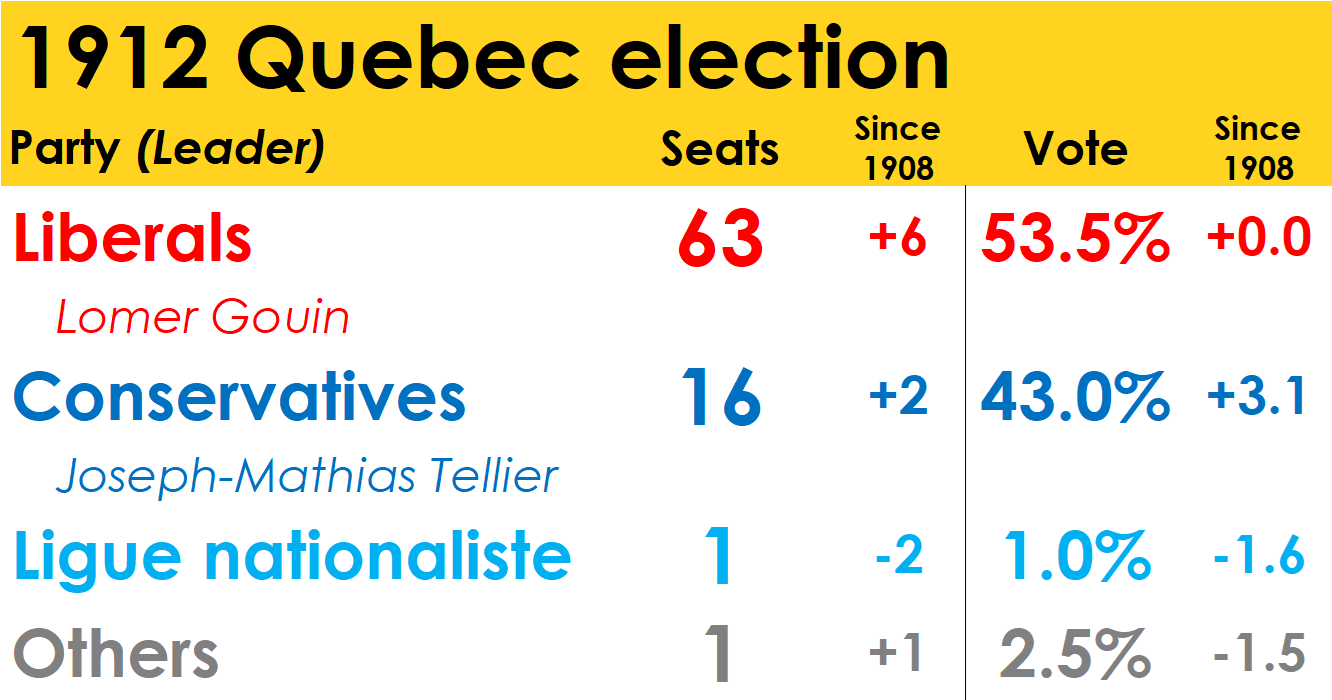

1912 Quebec election

Gouin extends the dynasty

May 15, 1912

Quebec was changing in the early 20th century, but its political stripes weren’t. The province was a Liberal bastion, would remain so for decades, and Lomer Gouin was one of the cornerstones of that early dynasty for the Quebec Liberals.

In the 19th century, the Conservatives and Liberals exchanged power back and forth. The influence of the Roman Catholic Church was strong, and the Conservative Party, those stalwarts of tradition and order, were the preferred option of the clergy. The Liberals were suspiciously too radical for the church, but could be swept to power on a wave of French Canadian nationalism — as occurred under Honoré Mercier after the hanging of Louis Riel by John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government in 1885.

But once Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals come to power in Ottawa, les Rouges were becoming more acceptable in the province and, after Mercier’s government was defeated in 1892 over corruption, the Liberals came back to power in 1897. They were re-elected in 1900 and 1904.

The following year, Simon-Napoléon Parent resigned and Lomer Gouin was sworn in as leader of the Quebec Liberals and premier. In 1908, he led the Liberals to another big win — the party’s fourth consecutive victory.

By 1912, however, the context had changed. Laurier and the Liberals had been defeated in Ottawa by Robert Borden’s Conservatives. They received help in Quebec from Henri Bourassa and his Nationalists, who aligned themselves with the Borden Conservatives against the policies of Laurier and Gouin. But the flirtation between Borden and Bourassa proved short-lived, and the Nationalists were losing steam already by 1912.

Nevertheless, the Quebec Liberals were still in good shape heading toward that year’s election. According to the Canadian Annual Review, “there was general prosperity, no pronounced agitation visible in the Province as to any particular subject, a dearth of discontent, and severe depression amongst the Nationalists. The Premier’s personal record was of the highest, the political career of his Cabinet since March 20, 1905, had been very largely peaceful, the policy pursued had been constructive and financial conditions excellent.”

The federal election having been held only a few months earlier, Gouin successfully attempted to remove federal issues from the provincial campaign. He didn’t want to run on or against Laurier’s or Borden’s controversial naval policies, or be weighed down by the policy of reciprocity with the United States that had driven Laurier to defeat in 1911. Reciprocity, Gouin told a crowd, “has nothing to do with the issue that will be decided on May 15.”

Instead, he wanted to run on his government’s record. And the record was largely good, with significant railway and road building, (relatively) progressive labour legislation, the annexation of Ungava in the north, a reduction of French Canadian emigration to the south and an expansion of the education system.

The franchise had been extended to nearly all men over the age of 21 and voters could no longer vote multiple times in as many ridings as they owned property.

Industrialization was running at full tilt, encouraging the further development of Quebec’s natural resources and hydro-electricity production. Investment, however, was largely coming from English Canadians and Americans.

This was a focus of criticism from Bourassa and the Quebec Conservative leader, Joseph-Mathias Tellier. A long-time MLA, Tellier accused the Liberals of mismanagement and of prioritizing foreign financial interests over Quebec “colonists”, who were trying to settle the under-developed regions of the province in places like Abitibi and the Gaspésie.

But the wind had gone out of the sails of the Conservatives and the Nationalists, particularly after Bourassa opted not to run for re-election, leaving Armand Lavergne as the only remaining Ligue nationaliste candidate on the ballot (in two ridings, still allowed at the time).

The Liberals prevailed, winning 63 seats in the expanded Legislative Assembly. Their share of the popular vote, 53.5%, was unchanged from Gouin’s first victory in 1908, and the Liberals successfully chased the Conservatives out of nearly all their seats south of Montreal and in the Eastern Townships, exchanging them for a few ridings north of the St. Lawrence.

It was an endorsement of the Liberal record of industrial development in Quebec and a setback for the Conservatives in Ottawa. His victory got people talking about what future might still be in store for Lomer Gouin, as the federal Liberals looked to the post-Laurier era that they assumed was about to start.

“His signal success in this week’s fight has given Canadian Liberalism just the encouragement it needed and at a good time,” wrote the Montreal Herald. “The Opposition at Ottawa will fight harder and more cheerfully and with more effect for the next couple of years because of him. How natural the question, “Why not Sir Lomer?” when Liberals think of the day when the wearer of the white plumes must take his resting time.”

But there would be no change coming. Laurier would remain leader of the federal Liberal Party until his death in 1919, and Gouin would stay on as premier until 1920. And the Quebec Liberals? Their dynasty would keep winning until 1936.

1931 Quebec election

Taschereau defeats a ‘bit of a rascal’

August 24, 1931

In 1931, Quebec was the last bastion of the Liberal Party.

After the defeat of Mackenzie King’s government in 1930 and the fall of Walter Lea’s Liberals in Prince Edward Island in early August 1931, only in Quebec did the Liberals still form government under Louis-Alexandre Taschereau.

The party was well-ensconced in Quebec after more than three decades in office. But the Great Depression was taking down governments left and right — and it looked like Taschereau’s would be next.

But you don’t stay in power for so long without learning a few tricks. In 1931, Taschereau employed a strategy that can still work today: if you can’t get the people to vote for you, just make sure they vote against the other guy.

The Quebec Liberals were on the ropes as the 1931 election approached. The province had been hit hard by the stock market crash, the collapse of demand for Quebec’s products and the drought in Western Canada.

The boom of the 1920s had been dependent upon external investment capital, world demand for Quebec’s forest and mineral resources, and the prosperity of western Canadian farmers, whose exports of wheat through the ports of Montreal and Quebec City and whose purchase of goods manufactured in Quebec were responsible for tens of thousands of jobs.”

With the ingredients for Quebec’s success under Taschereau wiped away by the depression, the province was struggling. The Liberals had run a lean administration so the province’s debt burden was low, but municipalities had few resources to cover the demands for relief for its desperate residents and couldn’t afford to pay for its share of R.B. Bennett’s federal relief program.

Buffeted by economic headwinds, Taschereau also faced a lively opposition.

The Conservatives were on the upswing after Bennett’s election victory in 1930, which included 24 seats from Quebec. These had been largely won in ridings where agriculture, and particular dairy production, was king after Bennett promised protective dairy tariffs to Quebec’s farmers.

This was a big problem for Taschereau, as his Liberals depended on (and dominated) Quebec’s rural ridings, whereas the Conservatives were more competitive in Montreal.

The Conservatives also had a new leader in Camillien Houde, who had taken over from Arthur Sauvé in 1929. A rabble-rousing orator and mayor of Montreal, he took over a party that was getting its act together with two newspapers newly being published and new offices being opened in both Montreal and Quebec City. A bit of a demagogue, Houde had no trouble linking Taschereau’s close relationship with the province’s powerful business interests to Quebec’s economic problems and crushing unemployment.

Houde was certainly a different character than the well-bred Taschereau. He was, in the words of author P.B. Waite, “a more charismatic but rougher man of the people [than Sauvé], an engaging rogue who looked like and sometimes acted like an all-in wrestler”

Taschereau had little regard for a man he called a “nonentity” and “the chief of a group of bobolinks, little birds that eat what they can when the horses have passed.” But he did respect his oratory talents and recognized that he could not compete with them. During the campaign, he would instead lean on some of his lieutenants to carry the Liberal message across the province, including Adélard Godbout, his future successor.

Godbout campaigned hard in the Gaspésie and Bas-Saint-Laurent regions, key parts of the province for the Liberals. At the time, these two regions were home to 10 of Quebec’s 90 seats. Today, they represent just six of 125. The Liberals held all the seats in the area and wanted to keep them, and accordingly Taschereau launched his campaign in Matane with Godbout by his side.

Godbout would be the chief spokesperson for the Liberals’ fight to keep the farmer vote on their side — Godbout was one of them and a credible voice on the issue. Houde, though, was going after them as well, campaigning on farm loans and receiving the backing of the influential Union catholique des cultivateurs, a big association representing farmers.

Feeling that he was losing the fight on the issue, Godbout begged Taschereau to match Houde’s pledge. But Taschereau wouldn’t budge, saying “I’d prefer to be defeated at the polls rather than expose our province to bankruptcy.”

But the Liberals couldn’t afford to lose their most important constituency. High unemployment in the cities likely meant they couldn’t make any inroads among the working class. And the prevailing view in Quebec at the time was that further development of the agricultural sector and the settlement of more of Quebec’s un-tilled land was the way out of the depression.

In addition to the aid from his lieutenants, Taschereau also got significant support from the federal Liberals. Though King wasn’t always on side with Taschereau on every issue, he recognized that the Liberals needed a win in Quebec. C.G. (Chubby) Power, a Quebec Liberal MP, was accordingly given the task of running the Quebec Liberal campaign.

He felt he faced an uphill battle and, two or three weeks into it, still thought he was on the losing side. Houde was attracting big crowds, but he was more of a spectacle than anything else, one commentator saying he was “an excellent clown but a poor politician.”

Perhaps sensing that the tide was beginning to turn, Houde’s promises became more and more reckless, his attacks against Taschereau more vindictive and personal. It was turning people off. The Liberals compounded matters by going after Houde’s record in the mayor’s office in Montreal, asking how he could run a province if he couldn’t run a city?

Against Houde’s increasingly radical proposals, Taschereau pledged “to avoid foolish and unrealizable promises; they won’t solve anything.” He nevertheless opened the spending taps on various relief projects during the campaign thanks to an influx of federal dollars — dollars that the Bennett government left to the provinces to decide how to spend. As the Conservatives ran six of nine provinces, that didn’t seem like a bad idea. During an election campaign in Liberal Quebec, it worked against Houde.

Also problematic was Bennett’s growing unpopularity. Power ordered Liberal candidates to talk about nothing other than “unemployment, butter and Bennett”. Taschereau gladly gave the spotlight to Liberal MPs at rallies in order to make the campaign about Bennett’s hated government rather than his own.

It was a smart tactic. While the mood for change had been strong in 1930, by 1931 the kind of change proposed by Houde seemed dangerous. Better the steady hand of Taschereau than another Bennett.

The result was a huge Liberal landslide — something that seemed unimaginable in the months before the election.

The Liberals won 79 seats, gaining five in a legislature that had grown by five seats since the 1927 election. Taschereau and the Liberals captured nearly 55% of the vote, a remarkable result for an incumbent government during the Great Depression.

The Liberals won nearly all of the rural ridings in the province, including a sweep in Godbout’s bailiwick of the Gaspésie and Bas-Saint-Laurent.

With 43.5% of the vote, Houde led the Conservatives to their best vote share since the party had been booted from office in 1897. His farm loan promises netted him more votes in rural constituencies, but it was not enough to deliver seats. The Conservatives only managed to win a single seat in Quebec City, one in Hull, a few ridings around Montreal and on the island itself.

None of them, though, were seats being contested by Camillien Houde. He went down to personal defeat.

Avoiding defeat by just a few dozen votes, though, was Maurice Duplessis in Trois-Rivières. With a little help from Taschereau.

The Liberal candidate in Trois-Rivières, sensing Duplessis as beatable, requested more funds for his campaign. But Taschereau suggested to Power that they refrain from giving their candidate a boost. The goal was to beat Houde, who Taschereau viewed as “a bit of a rascal and a vulgar fellow”. Better to have him defeated and be replaced as Conservative leader by someone like Duplessis, who Taschereau viewed as a man from “a good family” and a much more acceptable leader of the opposition than that scoundrel Houde.

He’d come to regret that.

1933 Quebec Conservative leadership

Duplessis becomes Conservative leader

October 4, 1933

Over the first decades of the 20th century, Quebec was a Liberal province. The party had come to power in 1897 and by the early 1930s it was still there.

The Conservative opposition had some hope that under firebrand Camillien Houde they could topple the Liberal dynasty in 1931, but Houde went down to defeat against the patrician Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, who deemed Houde “a bit of a rascal.”

While Houde suffered personal defeat, the Conservatives did manage to elect a small opposition caucus — including Maurice Duplessis, who had been singled out by no less than Taschereau as a potential successor to Houde and one that he would much prefer to see in the job.

Houde stayed on as Conservative leader despite not having a seat in the Legislative Assembly, but his caucus was restless. Open revolt occurred when he named an anglophone MLA as his parliamentary leader. The choice was rejected by other Conservative MLAs who instead chose Duplessis to lead them in the assembly. Having completely lost his sway over his caucus, Houde resigned.

Duplessis, first elected in Trois-Rivières in the 1927 election, was not the unanimous choice. Houde opposed him, as did a few MLAs. But the bulk of caucus backed him and there was expectation that they would forego the formality of a convention in order to give Duplessis the permanent job. But with a disunited party, Duplessis wanted to solidify his leadership with a convention — though, as the date for the convention approached, it seemed likely that Duplessis would be acclaimed anyway.

Not so. In a surprise move, Conservative MP Onésime Gagnon put his name forward as a challenger to Duplessis. It was a reversal for Gagnon, who only a few weeks earlier had invited Conservatives to rally behind Duplessis.

But Gagnon was preaching unity, which the Conservative Party did not have in Quebec at the time. Ever since the conscription crisis in 1917, the federal and provincial wings of the Conservatives were divided. Gagnon wanted to see closer ties between the two parties and for Quebec Conservatives to get solidly behind R.B. Bennett’s government in Ottawa. There was talk of third parties being formed in Quebec that would split the anti-Liberal vote and ensure another win for Taschereau.

Despite being a member of Bennett’s caucus in Ottawa, Gagnon had little support from his fellow MPs. They wanted to keep the peace between Duplessis and the federal party, and Gagnon had to dismiss reports that he was being pressed to withdraw by his colleagues, saying “I am in the contest to the finish.”

The convention was held in Sherbrooke and featured speeches by supporters of both Duplessis and Gagnon, as well as an address by the two contenders. Gagnon stressed unity, while Duplessis dismissed the notion that the party was disunited — and spelled out how he was more concerned with provincial than federal affairs.

The betting money was on an easy Duplessis win, but Gagnon put up more of a fight. Duplessis won a solid majority of 61% of the 550 delegates who voted, but Gagnon’s 39% was better than most had expected.

According to the correspondent for the Montreal Gazette, “the fight over, the great gathering broke in a tumult of applause. The rancor which has been engendered was forgotten and Mr. Duplessis and Mr. Gagnon came together on the platform with a hearty grip of the hand, and an exchange of mutual goodwill that told of their years of sincere friendship.”

Gagnon would return to Ottawa and suffer defeat, as most Conservatives did, in the 1935 federal election. Duplessis, too, would fail to dislodge the Quebec Liberals in the 1935 provincial election as a third party, the Action libérale nationale, split the vote. But Gagnon would make good on his promise of friendship to Duplessis, running under the new Union nationale banner in 1936 and sitting in Duplessis’s cabinets until he was rewarded with a posting to the lieutenant-governor’s job in 1958.

1936 Quebec election

Maurice Duplessis gets his first taste of power

August 17, 1936

For the first third of the 20th century, Quebec was Liberal. Federally, provincially — it didn’t matter. The province was reliably painted red.

But things were starting to sour for the provincial Liberals in the 1930s.

By 1936, Quebec had been governed by the Liberals for 39 years. The party had racked up 11 consecutive election victories since 1897, with the last four coming under the leadership of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau.

Though governed by a French Canadian, Quebec’s nationalism was still in its infancy. The finance ministry was traditionally given to an anglophone and the industrialization of the province was being undertaken by anglophone and American industrialists. The Catholic Church still held much sway and women were still barred from voting.

Throughout the long reigns of Taschereau and his predecessor, Lomer Gouin, the Liberals had nevertheless dragged Quebec into the industrial revolution. But new movements in the province were agitating for change — including within the Quebec Liberal Party.

Taschereau almost went down to defeat in 1935 when the opposition parties teamed up against him. From just 11 opposition members in 1931, Quebecers elected 42 in 1935. They were a mix of Conservatives (Quebec’s traditional party of opposition now under Maurice Duplessis) and, ominously for Taschereau, members of the Action Libérale Nationale.

The ALN was formed by disgruntled Quebec Liberals under the leadership of Paul Gouin, son of the former premier. They were primarily made up of younger members of the party who felt sidelined by the old-fashioned establishment. They were nationalist, had the backing of the clergy and agreed with the Conservatives to divvy up the electoral map between them. It nearly worked.

But Duplessis was a canny politician. Despite his Conservatives winning fewer seats than the ALN in 1935, he out-maneuvered the disorganized and divided leaders of the ALN. Eventually, he lured most of the ALN caucus to unite behind his Conservatives and form a new party: the Union Nationale.

Shaken by the results of the 1935 election, Taschereau tried to rejuvenate his cabinet with some younger ministers and promised to bring in measures like old age pensions and farm loans.

That his government was still in office at all was remarkable — other governments saddled by the Depression, including the Conservative government in Ottawa, had gone down to defeat. Responding to Duplessis’s claim in the legislature that Taschereau’s diminished government would soon be replaced, Taschereau said “we have had elections. You are still there and we are here. Strong governments, the [R.B.] Bennett government included, have disappeared. We alone survive.”

Nevertheless, the Liberals were in a tough spot. The economy was still stagnant, unemployment was still staggeringly high and the government’s revenues were too low to provide significant relief to Quebecers.

In the legislature, the Union Nationale filibustered and obstructed, preventing the Liberals from passing a budget. Then, in the public accounts committee, Duplessis leveled charge after charge of corruption against Taschereau’s government.

Day by day the evidence mounted … No single revelation was serious enough to excite or even surprise public opinion. It was the enormity, the pervasiveness, and the brazenness of abuse which first staggered, then enraged the people of Quebec. In the midst of unprecedented poverty and suffering, while leaders preached the virtues of self-reliance, family responsibility, private charity and ‘fiscal responsibility’, this behaviour was regarded as positively obscene.”

Duplessis spared no one — including members of Taschereau’s own family. For Taschereau, this was a step too far. He considered himself a gentleman, a seigneur, a representative of Quebec’s old aristocracy. To use such crass tactics was just not on.

Taschereau knew his time was up and he wouldn’t have his name or his family dragged through the mud any longer. It was recognized throughout the party that they needed a fresh face to give the Liberals a chance. So, Taschereau visited the lieutenant-governor, requested a dissolution and named his replacement: Adélard Godbout.

One of the stars of the last years of Taschereau’s government, Godbout was a good speaker with strong support in the rural parts of the province, particularly in eastern Quebec where he operated a farm and had taught agronomics before entering politics.

Godbout immediately tried to distance himself from the tainted Taschereau government, naming a new cabinet and presenting himself as the leader of a new, younger (he was 44) Liberal Party. There was certainly a contrast with the aged Taschereau. Godbout was not the patrician aristocrat his predecessor was. He was the descendant of humble farmers and, when in Quebec City during sittings of the legislature, he didn’t have a mansion on the Grande Allée to go home to like Taschereau did. He rented.

But Godbout could not make this distinction matter to voters. The Great Depression was attributed to the greed of heartless big industrialists and ‘trusts’ that held Quebecers back. These interests were seen (not entirely inaccurately) as being tied to the Liberals.

Duplessis, meanwhile, ran on cleaning up the administration. His prosecution of the Liberals in committee had given him tremendous publicity and cast him as the defender of the people.

Godbout and the Liberals knew they were the underdogs. Godbout, too, claimed he would run a clean administration and investigate any wrongdoings by the previous Liberal government. He took to the radio to present his platform, which including the electrification of rural areas and other measures to support agriculture. The party made nods in the direction of the ALN’s priorities in hopes of attracting the remnants of that party who had not gone over to the Union Nationale. But this campaign had little success. Nor did the assistance of the federal Liberal Party, which had won 60 of Quebec’s 65 seats in the 1935 federal election.

Duplessis just had the momentum on his side. There was a deep desire for change and he was the vehicle for it. Younger voters were behind him. The independent press was behind him. The Union Nationale held huge rallies, including one on August 12 at the Delorimier Stadium in Montreal, home of the Montreal Royals. The stadium’s 24,000 seats were packed and thousands more crowded the baseball field to hear Duplessis speak. Those who couldn’t get inside listened to him over loudspeakers outside the stadium.

The result was a landslide victory for the Union Nationale, which won 76 seats, an increase of 34 over the number of seats won by the Conservatives and ALN in 1935. The Liberals were reduced to just 14 seats.

Support for the UN was 56.9%, up nearly nine points from the combined performance of its predecessor parties. No party has since hit that level of support in a Quebec election.

The Liberals dropped more than seven points to just 39.4%. Godbout (by 20 votes) and five of his ministers went down to defeat. The Liberals were reduced to just three seats on the island of Montreal and eight in the surrounding countryside, with three more spread out in the Outaouais, Quebec City and the Bas-Saint-Laurent.

Duplessis’s victory ended 39 years of Liberal government, but the defeat wasn’t blamed on Godbout and he stayed on as leader. Duplessis’s first term as premier would prove short, as he called an early election in 1939 to challenge Mackenzie King’s prosecution of the Second World War. With the energetic support of the federal Liberal Party, this time Godbout was swept back into office.

It would provide Quebec with a short bout of progressive government (women finally got the vote and Godbout nationalized part of Quebec’s electricity system, among other achievements) before Duplessis and the Union Nationale returned to power in 1944. That election would kick-off his 16 years of nationalist, clergy-backed government that, in response, helped spark the Quiet Revolution.

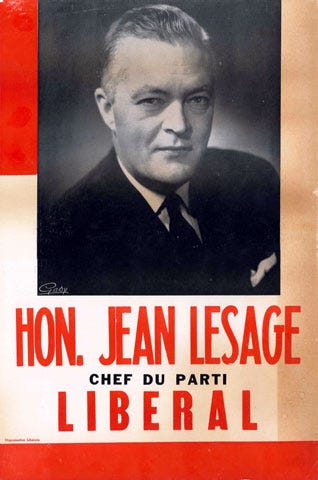

1958 Quebec Liberal leadership

L’équipe du tonnerre gets its leader

May 31, 1958

It was a dark time for the Quebec Liberals. Since their defeat 14 years earlier in 1944 at the hands of Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale, the Liberals were doomed to opposition against a domineering and dominating — some said despotic — Duplessis government.

Unable to dislodge the UN in 1952 and 1956, Georges-Émile Lapalme was facing challenges from within his own Liberal Party. He called for a convention to be held in the spring of 1958 where he would put his own name forward for re-election as leader, but by the end of April he had decided he would not be in the running after all.

That’s because some names had already stepped forward, and Lapalme feared that the Liberals would be further weakened, and perhaps replaced, if the party went through a divisive leadership contest.

There was serious concern within Quebec Liberals ranks in the late 1950s that they would be supplanted by a new party. After failing to put up much of a fight against the Union Nationale, other groups were agitating for a third option. Jean Drapeau, former mayor of Montreal, was widely rumoured to be considering to take his Civic Action League into the provincial sphere. There were also musings from people within the intellectual left-wing press, including one Pierre Elliott Trudeau, that a new progressive movement should spring up to challenge the Liberals as the alternative to Duplessis.

The intention of Jean Lesage to run might have been the clincher for Lapalme. Lesage, who served as minister of northern affairs and natural resources in Louis St-Laurent’s federal cabinet, was one of the few Liberal MPs to survive the Diefenbaker landslide of March 1958. Still the MP for Montmagny–L’Islet, just east of Quebec City, Lesage was the immediate favourite to replace Lapalme. He accordingly adopted the theme of unity for his leadership campaign.

He faced two main challengers. One was René Hamel, the MLA for Saint-Maurice and a frequent target of Premier Duplessis, who represented the neighbouring riding of Trois-Rivières. Hamel was respected within the party as he had served as Lapalme’s replacement as leader when he was away due to ill-health. As the only candidate with a seat in the Legislative Assembly (as it would be called until 1968), Hamel ran as the safe choice.

Paul Gérin-Lajoie, a Montreal lawyer and constitutional expert who had acted as legal counsel on two royal commissions, offered a fresh face and a new direction. A decade younger than his rivals, Gérin-Lajoie focused on education in his campaign.

A fourth candidate was Aimé Fautaux, a Montreal dentist and brother of a former lieutenant-government. But he was largely unknown and didn’t mount a serious campaign.

Lapalme said he wouldn’t back any candidate, but he admitted that most of his organizers had gotten behind Lesage. He was seen as the front runner who might win on the first ballot, but would lose if had to go to multiple ballots.

On the Thursday and Friday nights before the Saturday leadership vote on May 31, 1958, the three main contenders were at the Château Frontenac in Quebec City to greet delegates arriving by train from Montreal. According to Pierre Laporte, writing in Le Devoir, their booths were “garnished” by “very pretty dames et demoiselles who distributed signs with the pictures of the candidates while discretely inviting them to vote for one or another candidate.”

There was some 1,800 delegates who attended the first night at the Agriculture Building on the exhibition grounds and upwards of 4,000 on the second night. Speaking on the Friday, Lapalme appealed for unity within the party and warned against anyone thinking of stating a new movement.

Louis St-Laurent was on the platform when the results were announced after 8 PM — and it was a landslide. Lesage took 72.2% of the 873 ballots cast, with Gérin-Lajoie finishing a distant second at 16.6% and Hamel third with 11.1%. Fauteux earned a single vote.

Making his way to the platform, Lesage was greeted by a five-minute standing ovation. In his speech, he once again hit on the issue of unity.

“Unity has been and will remain my objective,” he said. “I feel that it is absolutely essential to achieve victory over the dictatorship which for too long has dominated our province without any regard for freedom or justice.”

Speaking of those who were thinking of starting up their own movements, Lesage said that “if they intend to set up new political parties outside the existing ones they will be playing into the hands of the Union Nationale and will accomplish nothing except to keep Mr. Duplessis and his supporters in office.”

Unity of a sort was achieved that night when Gérin-Lajoie, seconded by Hamel, moved to make Lesage’s win unanimous.

Lesage was still without a seat, but he declined to run in the byelection scheduled just a few weeks later in the riding of Matane. A UN stronghold, Lesage called the byelection call a trap set by Duplessis to try to embarrass the new Liberal leader. He’d stay on the sidelines and wait until the the Quebec election of 1960 when he and his équipe du tonnerre would storm the Legislative Assembly, kicking off the Quiet Revolution that would change the course of the province’s history.

1970 Quebec Liberal leadership

The Quebec Liberals choose a technocrat

January 17, 1970

The political winds were shifting in Quebec at the end of the 1960s. The Union Nationale had returned to power under Daniel Johnson in 1966, but his death two years later foreshadowed the impending fate of the party. Jean-Jacques Bertrand, by all accounts a decent-enough man but a bad politician, could not fill the shoes left empty by Johnson.

There was turmoil on the opposition benches, too. The leadership of Jean Lesage, who engineered the Liberals’ historic victory in 1960, was under serious strain following his defeat in 1966. The party had split over the issue of Quebec’s independence, with René Lévesque, once a star cabinet minister in the Lesage government, leaving to form what would eventually become the Parti Québécois in 1968. By the end of the next year, the pressure on Lesage to go was too great, and he resigned the leadership in 1969.

But who would replace him? Two of Lesage’s old cabinet ministers were clearly interested in the job. There was Pierre Laporte, the MNA for Chambly and the house leader in the National Assembly. There was also Claude Wagner, a Montreal MNA and the former justice minister.

Both in their 40s, the two were nevertheless seen as a holdover from the Lesage years. There was an appetite for something new, something modern, and the party’s establishment recognized the need for a third option on the ballot, even going so far as to commission a Chicago-based polling firm to gauge Quebecers’ opinions on who the ideal leader would be.

The person they described — young, educated, focused on economic development and competent administration — sounded a lot like Robert Bourassa. Just 36 years old, Bourassa was first elected in a Montreal riding in the 1966 election. Seen as an “intellectual” (his black-rimmed glasses completed the look), Bourassa was an ambitious and rising figure within the Quebec Liberal Party, even if he wasn’t nearly as well known as either Wagner or Laporte. But he had the party’s establishment behind him, the tacit endorsement of Lesage himself and plenty of financial resources — his wife’s family was one of the richest in Quebec.

Bourassa’s campaign was professional, organized and well-funded. It could afford to send out mailers to all 70,000 members of the party (the other candidates didn’t get their hands on the list) to gauge his support and send Bourassa around the province, meeting party members and delegates. When the convention, held at the Colisée de Québec, approached, his team reserved 2,000 hotel and motel rooms across Quebec City. They secured school buses to shuttle their supporters to and from the convention grounds, covering the fines that were meted out when the school buses got on the highways prohibited for these kinds of vehicles. Airtime on the local television station was booked to show continuous footage of Bourassa’s tour of the province, and his team in the Colisée was equipped with binoculars and radios to keep an eye on delegates and communicate with one another.

Wagner and Laporte felt that the campaign was being rigged against them. But they were also unable to drum up much support. Rumours of Laporte’s relationship with an organized crime boss limited his appeal. Wagner’s tough law-and-order message resonated in rural areas and among those who wanted to take a firm approach to the terrorist bombings of the FLQ, but turned off the youthful elements that were flooding into the party thanks to Bourassa.

Bourassa kept his message focused on the economy. He wasn’t a great orator with flair. He didn’t attack the other candidates or spend much of his time discussing Quebec’s place within Canada. For him, it was all about economic growth, and how economic growth would reduce Quebec’s social tensions and help solve its problems. After the tumultuous years of the Quiet Revolution and then the Union Nationale’s difficult relationship with the federal government (its slogan in 1966 was “Égalité ou indépendence”), a technocratic, economy-focused administration sounded good to a lot of Quebec Liberals — and, it would turn out, Quebecers in general.

The outcome was a solid first-ballot victory for Bourassa. Hal Winter, writing in the Montreal Gazette, described how the announcement of the results unfolded:

Throughout the early evening, the supporters of all three candidates kept up their continuous cheering and chanting, with the Wagner supporters leading the way.

The final round of the drama, which took [3.5] hours from the start of the voting until the results were announced by convention organizers, closed at 8:15 p.m.

“Pierre Laporte — 288 votes.”

The announcement was greeted by the faintest ripple of polite applause.

Then came the words: “Claude Wagner — 455…”

A deafening yell arose from the Bourassa corner, where the mounting tension was apparent on the faces of backers…

The cheering grew frenzied when it was calculated that Mr. Bourassa had topped Mr. Wagner by a crashing 388 votes and Mr. Laporte by 555.

As Mr. Bourassa, accompanied by his wife Andree and his son Francois [sic], sat stunned under the hail of handshakes and congratulations, organizer Jean Prieur leaped into the air, unable to repress his triumph. And veteran campaigner Alcide Courcy, tough-minded chief organizer of the Liberal Party, openly wept.

Bourassa wouldn’t get much time to savour his victory. The Union Nationale was approaching the four-year mark in office and Bertrand sent Quebecers to the polls in April.

The result was a sweeping victory for the Quebec Liberals and their young leader, though primarily due to the Parti Québécois (and the Créditistes) eating away at the Union Nationale’s support, rather than the win being attributable to a move toward the Liberals. Wagner would not be among the 72 Liberals elected, though, as he stepped away from politics (briefly, he’d later be elected as a PC MP and would vie for that party’s leadership in 1976). Laporte would be a member of Bourassa’s first cabinet but the year would end on a sombre note, with the October Crisis and the execution of Laporte by the FLQ.

In January 1970, that was all yet to come. With his victory in the Liberal leadership race, Robert Bourassa had taken the first step toward his long-held dream: to become the premier of Quebec.

1976 Quebec election

“Quelque chose comme un grande peuple”

November 15, 1976

It was an electoral victory that shocked nearly everyone in the country — including René Lévesque, the man who led the Parti Québécois to government for the first time in 1976. But, in retrospect, the PQ’s decisive defeat of Robert Bourassa’s Liberals was perhaps not so surprising after all.

Bourassa and the Liberals had been in office since 1970, when the party defeated the re-animated corpse of the Union Nationale, itself then led by an incumbent premier who, for the third time in the UN’s history, had to step into the shoes of a recently-deceased leader.

That election marked the arrival of the PQ on the provincial scene. Though it finished fourth in seats, the PQ placed second in the provincewide vote. Catching his opponents unprepared, Bourassa secured a huge majority government in the early 1973 election. The PQ finished second in both seats and votes that time, but the Liberals’ scale of victory was so great that the PQ formed the official opposition with only six MNAs, Lévesque not among them. Surrounding the rump opposition were 102 Liberals on the governing benches.

Three years later, Bourassa was contemplating another early election call. A few factors pointed in the Liberals’ favour. The péquistes were, as had often been the case, fighting amongst themselves. Montreal had just hosted the Olympics and the huge Baie-James hydroelectric project was still underway. Relations with the federal government of Pierre Trudeau were testy — the prime minister had dismissively called Bourassa a “hot dog eater”, referring to an awkward Maclean’s magazine cover featuring a posed photo of Bourassa having a hot dog for lunch — and Trudeau was openly discussing the possibility of repatriating the constitution without the approval of the provinces. Bourassa felt that could be an issue he could fight a campaign over, contrasting his defense of Quebec’s constitutional demands against the PQ’s reckless drive for independence.

But it was a risk. Bourassa was no longer very popular in his province. The polls were giving the PQ a sizable lead. The economy wasn’t great, unemployment was high. The Baie-James project, as important as it would be for Quebec’s future prosperity, was hugely over budget and the site of violent labour unrest. The Official Languages Act, better known as Bill 22, had angered anglophones and left many francophones unsatisfied. And the stench of corruption wafted around the Quebec Liberal Party.

The PQ had also adopted a new approach.

Recognizing that Quebecers were wary of the PQ’s sovereignty-association plan, the Parti Québécois abandoned its promise to start the process toward independence merely after the election of a PQ government. It instead pledged to hold a referendum. Lévesque talked less about sovereignty and more about the Liberals’ corruption, the PQ’s plans for progressive social legislation and reform of political financing. While the Liberals adopted the unimaginative slogan “non aux séparatistes” (“no to the separatists”), the PQ campaigned on “on a besoin d’un vrai gouvernement” (“we need a true/real government”).

Once the campaign got underway, it was clear that the Liberals were in trouble and that their efforts to make the election about the PQ’s separatism weren’t working. During a radio debate between Lévesque and Bourassa, the Liberal leader’s attempts to turn the discussion onto sovereignty were unsuccessful as Lévesque tore into the Liberals’ shady record on fundraising. Opinion appeared to be turning against Bourassa and a poll conducted two weeks before election day gave the PQ a lead of 12 points.

Lévesque and the Parti Québécois were cautious, though, having been disappointed in the previous two elections. While crowds in areas that had never before backed the PQ were greeting Lévesque (who, with strong grassroots fundraising, could finally afford to fly in a plane around the province), Liberal candidates kept their distance from Bourassa. The wind was blowing strongly against the Liberals, and the last-minute attempts to ratchet up fears of separation had little impact.

Even though Lévesque wouldn’t let any of his close associates talk seriously of victory and Bourassa kept up appearances, hoping to save as much of the furniture as possible, it was clear by the campaign’s end that the PQ had a real shot at government.

The scale of the PQ’s victory surprised many, Lévesque included. The party went from six MNAs to 71, jumping 11 points to 41.4% of the vote. Lévesque, after two previous failed attempts, finally won his own seat, one of many the PQ won in the suburbs around the island of Montreal. The French-speaking parts of the city went to the PQ as well, as did the Côte-Nord, the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region, the Bas-Saint-Laurent and most of the Mauricie, Abitibi and around Quebec City.

At the PQ’s victory rally in the Paul-Sauvé Arena, Lévesque had to improvise his speech — he had written two ahead of election day, but a victory speech wasn’t one of them. “On n'est pas un petit peuple, on est peut-être quelque chose comme un grand peuple,” (“we’re not a small people, we’re maybe something like a great people”) Lévesque shouted to the delirious crowd.

More breathtaking than the PQ’s gains were the Liberals’ losses. The party dropped 76 seats and 21 points, falling to just 26 MNAs and 33.8% of the vote. Half of the Liberals’ remaining seats were in Montreal and Laval, and the Liberals were lucky even to win those heavily-anglophone ridings. Some voters upset with Bill 22 voted instead for the Union Nationale in what proved to be a short-lived revival of the party. The UN won 11 seats, primarily in the Eastern Townships and the Centre-du-Québec, but also one on the West Island, where William Shaw was elected in Pointe-Claire.

Also elected was Camil Samson, leader of the Crédististes, in Rouyn-Noranda, and Fabien Roy, a former Socred booted from the party, who won in Beauce-Sud under the breakaway Parti national populaire banner.

Headlines the next day carried the message from Trudeau that Lévesque had won a mandate to govern, not to separate, a message that was echoed by Joe Clark and Ed Broadbent, national leaders of the Progressive Conservatives and New Democrats. Many editorialists in the province had a similar read of the results, tying the PQ’s victory to a rejection of the Liberals, not a rejection of Canada.

Bourassa resigned as leader of the Quebec Liberals (though he would be back). The Union Nationale and Créditistes also disappeared from the political landscape over the next few years, with only the PQ and Liberals winning seats in the next election.

Lévesque and the Parti Québécois would focus on governing for the next few years, putting off the referendum on sovereignty-association until May 1980, when 60% of Quebecers voted for sticking with Canada. But Lévesque’s plan to emphasize governance over independence in 1976 proved its mettle when it was invoked again in the 1981 election. Taking a referendum off the table entirely, the PQ won its biggest electoral victory ever.

1981 Quebec election

René Lévesque re-elected after referendum defeat

April 13, 1981

The election of a Parti Québécois government in 1976 was a watershed moment for Quebec, in some ways the culmination of the Quiet Revolution and in many ways changing the course of the province’s political history.

But after the rejection of the sovereignty-association option put forward by René Lévesque’s government in 1980, the PQ appeared to be adrift. With independence now off the table for the foreseeable future, what was the raison d’être of the PQ?

With the main project of the PQ’s first mandate ending in failure, Lévesque delayed the calling of the next election into 1981 — approaching the five-year term limit. Speculation that an election call was imminent was rife from the start of the year, and on the night of March 12, 1981, Lévesque announced to the National Assembly that it had been dissolved, and an election would finally be held on April 13.

From the outset, Lévesque promised that another referendum would not be held in a second PQ mandate, but many people believed that his party would not be given that chance anyway — especially those within the Quebec Liberal Party.

Now led by Claude Ryan since 1978, the Liberals were confident that victory would be a mere formality. They had won all 11 byelections held since 1976, picking up seats from the governing PQ but also the faltering Union Nationale.

That former hegemon of Quebec politics was a shadow of its former self, now under the leadership of Roch LaSalle, a Progressive Conservative MP. Support for the UN had collapsed when it was removed from office for the last time in 1970 and the party had nearly slipped away entirely after failing to win a seat in 1973. It managed a minor comeback in 1976 with 11 seats.

It was quickly apparent, though, that the Union Nationale was not going to be able to do nearly as well again. Polls put its support in single-digits, as Quebec’s politics evolved into the two-party system pitting the sovereigntist Parti Québécois against the federalist Liberals, a dynamic that would define the province’s politics throughout the 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s.

Despite the victory of the NON side in the 1980 referendum with 60% of the vote, the PQ did have some successes to point to during its first term in office. The province’s economy was out-performing Ontario’s and the PQ had provided a relatively clean administration.

The Charter of the French Language, better known as Bill 101, was certainly divisive and controversial, but was popular among francophones. The PQ had brought in public automobile insurance and instituted new political financing laws that were well ahead of its time, banning corporate donations and limiting donations by individuals decades before other jurisdictions in Canada.

The PQ took this record to voters with good effect. Writing later in his autobiography, Lévesque said: “Of the seven election campaigns that I’ve been through, this one was by far the easiest … People were visibly happy to see us. Did this warmth hide something like an intention to console us? Maybe a wave of remorse had installed itself in many hearts after the sad [referendum] night of 20 May 1980.”

Ryan’s Liberals, arrogant and overconfident, waged a front runner’s campaign. But the bubble burst when a couple of mid-campaign polls showed the Liberals trailing the PQ by a significant margin — and on track for defeat.

The Liberal leader’s style was not going over well with voters. David Thomas of Maclean’s painted a vivid portrait.

His craggy head pokes through the doorway and scans the dining room like an aged tortoise hungry for an inattentive fly. Then, gnarled hand cocked for action, Claude Ryan strikes at the nearest table where surprised lunchers suddenly must shift from picking the bones of a barbecued chicken to grasping the candidate’s insistent claws. There’s no band, but from a cassette recorder slung over the shoulder of an accompanying aide crackles the tinny Liberal campaign theme which even Ryan’s chief communications adviser, Gilles Liboiron, admits “has a depressing effect on audiences.”

As the campaign turned for his party, Ryan undermined his own credibility when he announced some spending promises after previously criticizing the PQ for its deficit spending.

The campaign ended as a mirror image of how it had begun, with the PQ confidently cruising to victory and the Liberals desperately trying to avoid defeat. But the tables would not turn.

For a moment, though, it appeared that the Union Nationale, of all parties, had returned from the dead. With strikes impacting coverage of election night by Radio-Canada, all eyes were turned to TVA and Radio-Québec, who had teamed up to use a new computer system to report the election results.

It was a mistake.

Claude Ryan was reported to be barely registering a pulse in his own riding as the Union Nationale stormed ahead. A Marxist-Leninist candidate was leading in Montreal and another was declared elected in Quebec City, while UN candidates throughout the province were running in first.

It took a long time before the TV presenters realized something was going wrong (though that didn’t stop them from first trying to explain the surprising turn of events). Lévesque writes that he had given up on the French-language channels and had to turn to English-language media to find out he had, in fact, won.

The PQ took 80 seats, nine more than the party had captured in 1976 (the electoral map had increased from 110 to 122 ridings). Support for the party was up six percentage points to 49%, which still ranks as the best election performance of the party in its history.

The PQ won eastern Montreal, most of Laval and the suburbs north and south of the metropolis, captured all but one seat in Quebec City and gained seats from the Union Nationale in central Quebec.

The Liberals were also up in both seats and support, gaining 16 seats and 12 points to end with 42 seats and 46% of the vote. That three-point gap between them and the PQ was much smaller than the polls had indicated, but the inefficiency of the Liberal vote meant the party had only about half as many seats as the PQ.

The Liberals swept the West Island, but most of their seats elsewhere in the province were limited to the Outaouais and the Eastern Townships. Ryan would resign the leadership and be replaced by Robert Bourassa, returning as Liberal leader after governing the province from 1970 to 1976.

LaSalle and the Union Nationale, in the end, did not win a single seat and took only 4% of the vote. This would effectively be the end of Maurice Duplessis’s old party for good, and LaSalle would return to federal politics.

The election victory would be a last high point for Lévesque, as his second term in office was tumultuous. The economy took a turn for the worse, unemployment surged and there was significant labour strife in the province. Lévesque would be out-manoeuvred (or betrayed, depending on your point of view) by Pierre Trudeau and the provincial premiers in the repatriation of the constitution, a document that still does not have Quebec’s signature.

The arrival of Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government led Lévesque to pursue a more collaborative approach with Ottawa (the so-called beau risque) that cleaved the Parti Québécois in two, divisions that led to Lévesque’s resignation as premier and PQ leader in 1985. The party would be swept out of office later that year by Bourassa in one of the Liberals’ biggest victories of the modern era.

A far cry from the PQ’s heights, and Liberal lows, of 1981.

1998 Quebec election

Bouchard wins — and loses

November 30, 1998

In retrospect, the Quebec election of 1998 was perhaps one of the most important in the modern history of the province. It effectively closed the door on another referendum campaign and set the province on its current course, where issues related to language, culture and the economy have been more important than the old battles between sovereigntists and federalists.

But that was yet to come. In 1998, emotions were still raw.

The preceding decade had been a tumultuous one. The province had been at the centre of the constitutional negotiations that led to the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords, whose failures briefly pushed support for independence to over 60%. Then, the federal landscape of Quebec’s politics was transformed with the creation of the Bloc Québécois and its rise to official opposition status in 1993.

The Parti Québécois’s election victory in 1994 put Quebec on course for the 1995 referendum on independence, which the NON forces won with just 50.6% support. The result cost Quebec its premier, as Jacques Parizeau resigned in favour of Bloc leader Lucien Bouchard, who took over in 1996.

When Parizeau had faltered as head of the OUI forces in the early stages of the referendum campaign, Bouchard stepped in to shore up their fortunes. His near-death experience with a bout of flesh-eating disease that cost him his leg, and his leadership during the ice storm, had given him almost mythical status in Quebec by 1998.

With Bouchard’s pledge to put Quebec back on the path to another referendum, the beleaguered Quebec Liberals were searching for a savior that could save the party — and Canada.

They thought they had their saviour in Jean Charest, then leader of the Progressive Conservatives in Ottawa.

Though the PCs were still reeling from their thrashing in 1993, Charest had been building up his resume. He was a key player in the NON side of the 1995 referendum and had led the PCs back to some respectability with 20 seats, including five in Quebec, in the 1997 election. He was reluctant to give up on his dreams of becoming prime minister, but Charest was finally convinced to make the leap to the provincial sphere as head of the Quebec Liberals.

It wasn’t an easy jump for a Tory who had spent over a decade fighting federal Liberals, but the Quebec Liberals were an awkward coalition of federalists that included Liberals, Conservatives, anglophones and francophones, united in their opposition to the Parti Québécois and its independence project.

Bouchard and Charest had plenty of history as key Quebec members of Brian Mulroney’s cabinet, and Bouchard did not hesitate to question Charest’s Quebec bonafides. He claimed that a vote for Charest, the former PC leader, would be a vote for Jean Chrétien, the Liberal prime minister who was deeply unpopular in nationalist circles. But the arrival of Charest had the effect Quebec Liberals were hoping for, pushing the party into the lead in provincial polls.

Bouchard had adopted an ambiguous position on another referendum, promising one would be held once “winning conditions” were met. With polls showing Quebecers against holding another referendum so soon after the last one, this was a risky position for Bouchard to take. But he, too, was leading a shaky coalition of sovereigntists united around the idea of independence.

Charest adopted an ambitious platform of tax cuts and laissez-faire economics that pushed the Liberals to the right, earning him comparisons to Mike Harris and his “Common Sense Revolution” in Ontario. He argued that the sovereignty debate was holding Quebec back and preventing the province from attracting investment.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1998, polls gave the Quebec Liberals around 50% support. Once the campaign started, though, the polls tightened. The Liberals weren’t helped when comments made by Chrétien suggested that the door for reforms to Quebec’s constitutional status within Canada was shut.

The campaign featured lots of debate over policy, whether it be on the economy or health care, where cuts made by the PQ made them vulnerable. But the close race in the polls masked Bouchard’s biggest advantage — his 20-point lead among francophones.

With the trends looking worse for the Liberals in the final stretch, the party turned its focus away from policy and toward the spectre of another referendum, emblazoning the slogan “No More Referendums” on their campaign bus. It looked like an act of desperation, as polls put the Liberals five points back across the province — the kind of gap that would produce a crushing PQ majority. But it might have worked.

The results demonstrated just how polarizing the referendum question still was. Little changed from the last election in 1994. The Parti Québécois won again, but it was not the resounding victory Bouchard hoped would kick-start another drive for independence.

The PQ won 76 seats, one fewer than they had in 1994. Their popular support fell 1.8 points to 42.9%, putting them just behind the Liberals. With a concentration of support in anglophone ridings, Charest was able to win the Liberals the most votes with 43.5% but the party nevertheless finished with only 48 seats, a gain of one.

Just a few seats changed hands, the Liberals flipping Anjou in Montreal, Limoilou in Quebec City and Bonaventure on the Gaspé Peninsula, along with the riding of Sherbrooke, which Charest himself wrested away from the PQ.

The PQ, meanwhile, flipped the Liberal seats of Bertrand (Laurentides), Frontenac (Eastern Townships) and the Îles-de-la-Madeleine riding.

The results were far better than expected for the Liberals, whose crushing defeat was widely predicted and so would end Charest’s political career. Instead, he won a seat in the National Assembly and a moral victory in topping the province wide vote, a feat that halted Bouchard’s plans for another referendum.

One of the other surprises of the night was the performance of Mario Dumont’s Action Démocratique du Québec, a conservative nationalist party that pushed for greater autonomy, but not independence, for Quebec. Dumont won just a single seat again (his own), but by providing a middle way he increased his party’s share of the vote by 5.8 points to nearly 12%. He wouldn’t be sitting on the opposition benches by himself for much longer.

What was supposed to be an important step towards the birth of an independent Quebec turned out instead to be the last step for Bouchard, who would resign as premier before the next election. Charest would win that vote in 2003 and Dumont would emerge as the new leader of the official opposition in 2007, signaling the first swing Quebec’s nationalists would have away from the old “national question” to the issues surrounding identity that dominated Quebec’s nationalist politics for the next 15 years.

2008 Quebec election

Jean Charest gambles and wins

December 8, 2008

After four years in office, the Quebec Liberals under Jean Charest were reduced to a slim minority government in 2007 as Mario Dumont’s Action Démocratique du Québec made big inroads at the expense of both the Liberals and the Parti Québécois under André Boisclair.

But it wasn’t long before support for the inexperienced ADQ tanked. As the Liberals moved back into the lead in the polls, Charest claimed he needed “two hands on the wheel” in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis and pulled the plug on his minority government less than 20 months into its second mandate.

Though the ADQ was the incumbent official opposition, the Liberals’ primary opponent was once again the PQ, now under the leadership of former cabinet minister Pauline Marois.

By the end of the campaign, the main issue wasn’t what was happening in Quebec, but rather what was happening in Ottawa. When Stéphane Dion, Jack Layton and Gilles Duceppe teamed up to try to bring down Stephen Harper’s government, the Conservatives went hard against the coalition of “socialists and separatists”. The rhetoric sparked a blowback in Quebec, where some voters were put-off by the attacks on the democratically-elected Bloc Québécois MPs.

It might have helped boost the PQ a little in the last days, but it also made the case for Charest about the necessity of having a stable majority government in Quebec City to avoid Ottawa-style shenanigans. When the results came in, Charest got what he asked for.

The Liberals picked up 18 seats, winning 66 with 42% of the vote, a gain of nine points since Charest’s 2007 performance. But the Parti Québécois also rebounded, gaining 15 seats to finish with 51 and 35% of ballots cast. Both Charest and Marois would stay on as leaders, facing off once more in 2012.

But Dumont was a casualty. He was re-elected in his Rivière-du-Loup riding, of course, but his party dropped 34 seats, ending with just seven and 16% of the vote. Dumont, who had spent years as the party’s sole MNA since its creation in 1994, resigned on election night.

While the election might have seemed like the return of the two traditional political rivals in Quebec, it actually turned out to be an election that led to the rise of two other parties.

With the resignation of Dumont, the ADQ became directionless. This left an opening for a former PQ cabinet minister named François Legault to start his own centre-right party, the Coalition Avenir Québec, into which the ADQ dissolved itself.

And 2008 marked the first seat win for a small left-wing party, Québec Solidaire.

Over a decade later, the Quebec Liberals were struggling for relevancy outside of its traditional anglophone base as the CAQ gobbled up its francophone vote, while the Parti Québécois was desperately trying to avoid being supplanted by Québec Solidaire.

It’s the kind of thing that would have seemed unthinkable in 2008.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Quebec, the National Assembly and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Quebec Before Duplessis: The Political Career of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, by Bernard L. Vigod

Godbout, by Jean-Guy Genest

La Révolution dans l’ordre: Une histoire du duplessisme, by Jonathan Livernois

Attendez que je me rappelle…, by René Lévesque

Honoré Mercier et son temps, Tome 1 by Robert Rumilly

Lomer Gouin: Entre liberalisme et nationalisme, by Mathieu Pontbriand

Robert Bourassa, by Georges-Hébert Germain

René Lévesque: Un homme et son rêve, by Pierre Godin

Patrician Liberal: The Public and Private Life of Sir Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, by J.I. Little

Alexander Mackenzie: Clear Grit, by Dale C. Thomson