#EveryElectionProject: Ontario

Capsules on Ontario's provincial elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about the elections in Ontario.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1875 Ontario election

Ontario gets the secret ballot

January 18, 1875

In the 19th century, voting could be a dangerous affair. Not everyone had a vote, of course. Women didn’t and neither did the men who didn’t meet the property qualifications.

But those who did have a say literally had a say — voting was done in public and out loud.

Without a secret ballot, votes were liable to be acquired not by persuasion but by bribery, booze or brawls. Money was paid out, copious amounts of alcohol was provided and, when that failed, a recalcitrant elector could be threatened with violence or physically prevented from voting by gangs of toughs.

But by the 1870s, Canada was starting to mature as a democracy and governments implemented changes to their voting systems to expand the franchise to more (male) voters and arrange for a secret ballot. Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal government in Ottawa leveled the playing field at the federal level, while in Ontario it was Oliver Mowat’s Liberals who brought in the secret ballot with bipartisan support.

(Implementing compulsory voting, though, was one step too far for Mowat, who shut down a fellow Liberal’s proposal to make voting mandatory in Ontario.)

One of those democratic reforms of the 1870s was actually responsible for bringing Mowat to the premier’s office.

In the first years after Confederation, being an MP wasn’t a full-time job. In fact, it was permitted for MPs to not only sit in the House of Commons but also in their provincial legislature. When that practice was finally ended in 1872, some MPs had to make a hard decision. That included Liberal MPs like Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake, the latter who just happened to also be the premier of Ontario.

When Mackenzie and Blake decided to opt for the federal scene, they casted about for a provincial replacement. They found one in Oliver Mowat, who had served in the pre-Confederation parliament and was now sitting on the bench as a judge. Mowat didn’t require much persuading and he took the job — one that he would hold for more than two decades.

At the end of 1874, however, it was time for Mowat to seek his first mandate from the people. More Ontarians would be eligible to vote than ever before and, for the first time, they could do so with a free conscience. On December 21, Mowat set the date for his first test as leader for January 18, 1875.

The Conservatives, who under John Sandfield Macdonald had been ousted from power in 1871, were not in a great position. Their leader, Matthew Crooks Cameron, seemed distracted. Part of his focus was in running his legal practice and even a friendly newspaper editorialized that “Mr. Cameron has not bent his whole mind to the task of leading the Ontario Opposition.”

The party was still reeling from the Pacific Scandal that had derailed John A. Macdonald’s government in 1873 and Mackenzie’s Liberal victory in the 1874 federal election was still fresh in voters’ minds. Cameron and the Conservatives thought that Mowat had a vulnerability in his government’s lavish spending, but the Liberals were still able to report a surplus and Mowat, while not an engaging speaker, was “persuasive with his earnestness and mastery of facts.”

He also received some help on the stump from Mackenzie and Blake, while the prime minister indirectly assisted Mowat by delaying the declaration of a general amnesty for the Métis who participated in the 1870 Red River Rebellion until a few days after voting took place.

According to the Liberal Globe, “the elections passed off in [Toronto] yesterday in a very quiet and orderly manner, as was to have been expected under the ballot system of voting. Had it not been for the fact that all the places in which intoxicating liquor is sold were closed all day, a casual visitor to the city would scarcely have known that a fierce contest between two parties … was waging from nine o’clock in the morning until five in the evening.”

When the ballots were counted, the Liberals emerged victorious with 50 seats in the enlarged legislature, their majority re-established thanks in large part to their traditional strength in southwestern Ontario.

The Conservatives took 35 seats, while two Independent Conservatives and one Independent Liberal were also elected. The share of ballots cast was close at 47.6% for the Liberals to 46.3% for the Conservatives, but the Liberals won many more seats by acclamation than the Conservatives did. Had contests taken place in those ridings, the Liberals’ margin of victory would have been larger.

Cameron wouldn’t lead the Conservatives into another election, but Mowat would establish himself as the longest serving premier in Ontario’s history. His unmatched winning record began in 1875, when Ontario proved it could run an election fairly — at least by 19th century standards. Seventeen contests were voided either due to a recount or because of “corrupt practices”. Some old habits die hard.

1886 Ontario election

Another win for Oliver Mowat

December 28, 1886

In the late 19th century, elections could be (and often were) decided over religious issues. That was the case of the Ontario provincial election held on December 28, 1886.

By then, the province was well into a long period of dominance by the Liberal Party. The premier, Oliver Mowat, had already been in power since 1872 and had three electoral mandates under his belt. Ontario was prosperous and Mowat had secured provincial rights in a series of stand-offs with the Conservative government of John A. Macdonald in Ottawa.

But after a close contest in 1883, Mowat wanted to avoid putting things to chance again. It hadn’t helped that the last election came shortly after a national Conservative victory in 1882, so Mowat decided to call an early election to get ahead of another expected Macdonald victory in 1887.

His government was running a big surplus, the electoral boundaries had been re-drawn to the Liberals’ advantage and the party’s organization had been improved since 1883. It was as good a time to go to the polls as it ever would be.

The Conservative opposition was led by W.R. Meredith, and had been since 1878. After two consecutive defeats, this time Meredith hoped to exploit the Liberals’ ties to the Catholic Church.

An anti-Catholic campaign was spearheaded by the Toronto Mail. It was a potent issue in 1886, coming shortly after the North-West Rebellion of 1885 and the execution of Louis Riel. The Mail charged that Mowat was unduly influenced by the Catholic Church in his support for separate schools, patronage appointment of Catholics and in allowing Catholic students and objecting teachers to opt-out of readings from the Bible in public schools.

Meredith also tried to tie Mowat to the newly-elected nationalist government of Honoré Mercier in Quebec, a relationship that he said suggested pro-Riel sympathies in the Ontario premier.

But Meredith tried to have it both ways — in part out of deference to John A. Macdonald, who objected to the sectarianism of the Mail. The Macdonald Conservatives, after all, were still chasing the votes of Quebecers and Irish Catholics. So, Meredith let the Mail do the dirty work while he took ambiguous positions on religious issues. According to the Globe, while Meredith did not “travel on the Protestant horse” he also did not mind “the steed being hitched to his buggy”.

Mowat defended himself adroitly, saying he aimed to treat Protestants and Catholics equally and, with his long experience as premier of a prosperous province, the Liberals were re-elected — again.

Mowat scored his fourth consecutive victory, in part (but not wholly) thanks to his support among French Canadians and Irish Catholics. The Liberals won 57 seats and 48% of the vote, a gain of nine seats from the 1883 result. The Conservatives were close behind at 47% of the vote, but won just 32 seats, five fewer than in 1883. An independent was also elected and Labour candidates captured 4%.

This would not be the last time that Mowat and Meredith would face-off as opponents. Mowat would defeat the Conservative leader again in 1890 and 1894, before resigning as premier to take a cabinet post in Wilfrid Laurier’s new Liberal government in 1896 — another election in which religious divisions would play a decisive role.

1898 Ontario election

Prelude to a fall in Ontario

March 1, 1898

In early 1898, the Ontario Liberals tried to do something they hadn’t done in over 20 years: win an election without Oliver Mowat.

Mowat, Ontario’s bespectacled longest-serving premier, had resigned to take up a new post in Wilfrid Laurier’s federal government in 1896 after 24 years in office. His Liberals had governed the province without interruption since 1871, as dominant in Canada’s largest province in the last decades of the 19th century as John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives had been in Ottawa.

Trying to fill Mowat’s big shoes was his most senior minister, Arthur Sturgis Hardy, whose diabetes made him hesitate to take the position until he “concluded not to let it pass by. There were other good men who could have taken the place, and it would not have gone begging; but you know how very difficult it is in this wicked world to let high honors pass by.”

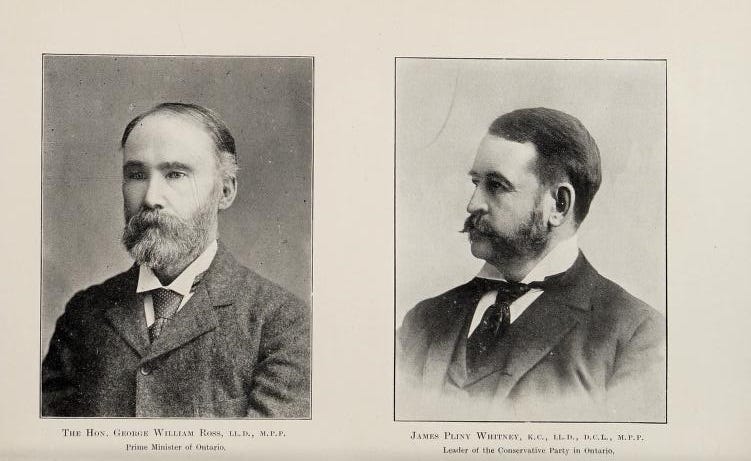

Hardy took over the redoubtable Liberal machine and seemed in a good position with a friendly federal Liberal government handing out patronage and favours. The Conservatives had never mounted much of a challenge, though their new leader, James Pliny Whitney, brought new energy and a tireless work ethic to the leadership of their party. Still, the Conservatives were short on money and organization and Whitney’s task would be a daunting one.

Some things, however, were starting to go Whitney’s way. The 1894 election had featured a number of parties on the ballot, including the Patrons of Industry, a farmers’ party, and the anti-Catholic Protestant Protective Association. The Conservatives’ own hostility to Catholics, particularly in terms of separate education rights, had limited their appeal among this important electorate and the presence of the PPA further reduced their base. The Patrons also cut into some of the Conservatives’ support.

But by 1898, the PPA was no longer a force and the Patrons had largely been subsumed into the Liberal Party. Whitney also wanted to put behind him and his party its anti-Catholic past. He had sent signals in that direction during the 1896 federal election when he kept his party out of the divisive Manitoba schools question. At a fraught nomination battle in the riding of Toronto South ahead of the provincial vote, he successfully backed a prominent Catholic candidate, much to the consternation of the old school within the party.

Hardy, meanwhile, was not getting the kind of support he had expected from the Laurier government to grease the palms of Catholics in Ontario and he hesitated to name an important Catholic Liberal politician to high office in his government. Together, this weakened the Liberals’ support among this key voter base that they had been able to count on in election after election at a time when the Conservatives had ruled themselves out as an option for Catholics.

The narrowing of the contest to a two-horse race between the Liberals and the Conservatives resulted in a far tighter outcome than the confident Liberals expected. Hardy and the Liberals held on to 51 seats, down eight from the combined totals of Liberals and Patron/PPA-affiliated Liberals in 1894. The Liberals roughly matched the Conservatives in the popular vote, but that represented a big increase for the Conservatives as much of the PPA as well as some of the Patron vote went their way.

The Conservatives, who seemed destined to opposition for eternity, had made serious inroads under Whitney. It was only the Liberals’ stronghold of southwestern Ontario that saved the party from defeat.

As was the style at the time, both sides accused the other of under-handed tactics. According to G.M. Grant, principal of Queen’s University, “on polling day in cities like Kingston, Toronto, London and Hamilton … a seedy-looking lot loafed round the booths, and it was evident to the most careless observer that they were waiting to get their two dollars apiece before entering. Hundreds got what they waited for. Both sides bought.”

As was also usually the case, the results in dozens of individual ridings were challenged in the courts, but Hardy’s government survived. Not the premier, though. His health made it impossible for him to continue and he resigned in 1899. He died two years later.

His successor, George William Ross, would win one more election for the Liberals — barely — before Whitney stormed into office in 1905, ending one of the longest political dynasties in Canada’s history.

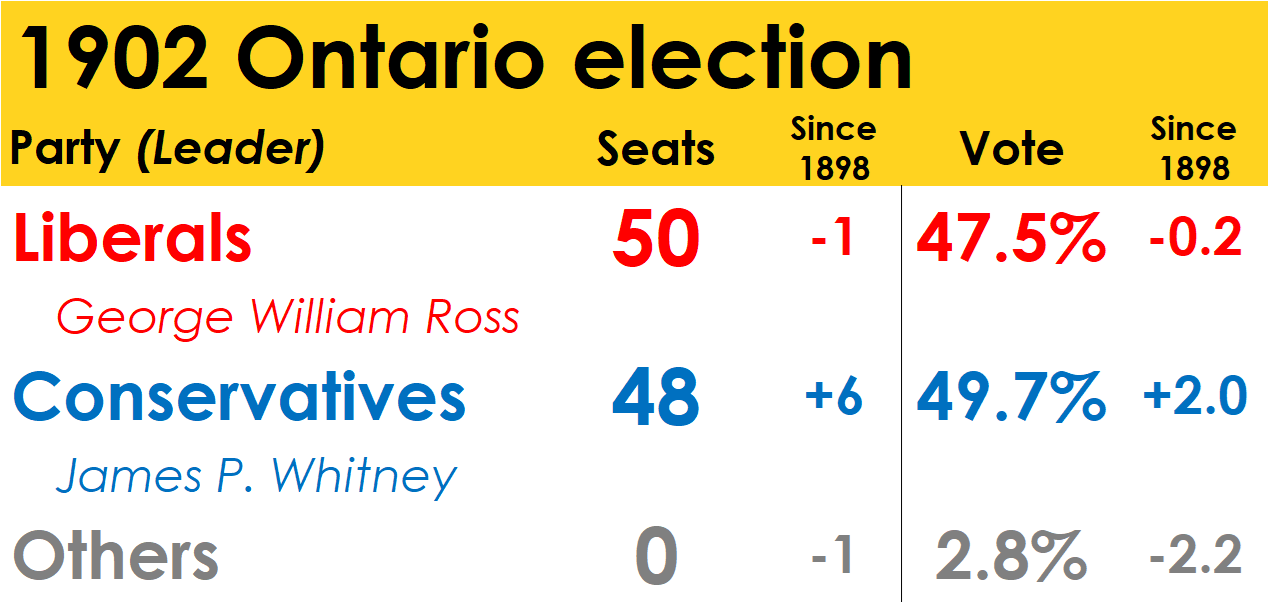

1902 Ontario election

An election decided by the narrowest of margins

May 29, 1902

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ontario Liberals were the natural party of government, having run the province for the previous 30 years. Most of that tenure was under Oliver Mowat, but since his departure for federal politics in 1896 things had been going badly for the Grits.

His first successor, Arthur S. Hardy, proved he couldn’t fill Mowat’s shoes and very nearly lost an election in 1898. Suffering bad health and worse debts, Hardy resigned in 1899 and was replaced by the 58-year-old George William Ross. He had looked after the education portfolio in Mowat’s cabinet, was a temperance supporter and

“…probably best described himself when he wrote to Laurier: ‘The Ontario Liberal is not a radical in the English sense of the term. He is a cross between the radical and the conservative.’ Ross was very much that hybrid.”

On the opposition benches, the Conservatives had also made a change from the long era of election-losing leadership of William R. Meredith. Since 1896, the Conservatives had been under the leadership of James Pliny Whitney, MLA for Dundas since 1888.

Whitney was a tireless campaigner and he led the Conservatives to significant gains in the 1898 election.

By early 1902, it was a well-known secret in Toronto that there would be an election in the spring. So, after the legislature shut down in March, Whitney kicked off a seven-week speaking tour across the province. Unlike Meredith, who was only too happy to incite religious strife between Catholic and Protestant, Whitney campaigned with a high-profile Catholic candidate in an attempt to wrest away a voting bloc that had long backed the Liberals.

The campaign turned on a few issues, including the development of hydroelectric power in Ontario. The debate was over whether power generation should be in public or private hands — and it was the Conservative Party that wanted to see it turned over to public ownership.

“The Government at the switch; not corporations” was the Conservative battle-cry, just one of many ways in which Whitney’s Conservatives were populist class warriors, pitting Whitney’s pledges to help the working man against the Liberals’ alleged cozy relationship with big business. It was the kind of rhetoric popular in the United States, which in 1902 was only in the early days of “trust-busting” Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency.

Prohibition was another issue. A supporter himself, Ross was pressured by temperance advocates to come forward with legislation to ban booze in its entirety. Knowing that it was probably not a good political move, Ross instead promised new temperance laws (with plenty of exemptions) and a referendum that would be held later in 1902 that had to meet onerous turnout requirements to count.

Prohibitionists saw it as a half-measure, while Whitney tried to woo moderates with promises of more enforcement of existing regulations.

The development of “New Ontario”, as northern Ontario was then known, was another frequent focus of discussion, with Ross lauding the work the Liberals had done to development the north while Whitney promised even more (and with less corruption).

While Whitney had a catchy campaign song called “Whitney Will Win”, Ross put a fresh face on an old Liberal government, someone who was seen as “distinctly stronger personally than Hardy was four years ago.” The focal point of the Liberal campaign, Ross toured the province and did just enough to keep his government in power.

The Liberals emerged with 50 seats and a tiny majority, as Whitney and the Conservatives won 48. His party made gains in the Liberal stronghold of southwestern Ontario and he elected a Franco-Ontarian and other Catholic candidates. But even though Whitney’s party won more votes — 49.7% to the Liberals’ 47.5% — he had failed to win power.

And by the narrowest of margins. The Liberals secured the seat of Grey North by only five votes. Had three people voted differently there, the two parties would have been tied at 49 seats apiece. (Alex Mackay’s victory here was re-affirmed in a byelection held in early 1903.)

But a two-seat majority was tough for Ross to manage, and the death of an MLA nearly meant the death of his government. Ross would stumble on for three more years, leading a tired government troubled by the baggage of more than three decades of rule. When he finally called an election to settle matters in 1905, his party was met with a crushing defeat and James Whitney became what Ontario had not seen in more than a generation: a Conservative premier.

1926 Ontario election

Howard Ferguson wins, Prohibition loses

December 1, 1926

Welcome to the 1920s, when prohibition (and ignoring prohibition) was all the rage. Ontario was no exception, but the province was divided on the issue. In the 1924 plebiscite on repealing the Ontario Temperance Act, brought into force during the First World War, the attempt failed by a narrow margin — 51.5% for continuation to 48.5% for repeal.

But by 1926 the Ontario government was ready to take on prohibition again.

That government was led by G. Howard Ferguson and the Conservatives, who had come into power in 1923 when they defeated the single-term government of the United Farmers of Ontario.

Ferguson wanted to institute government control of the liquor trade, in order to reap the tax revenues but also to do a way with a system that was being largely ignored. It was a thorny issue, though, as the Conservatives were split on whether to be “wet” or “dry” and in the 1924 plebiscite a majority of the ridings held by the Conservatives voted against repeal.

But Ferguson was a cunning, colourful and combative politician and wasn’t about to shy away from a fight, particularly when he saw the weakness on the opposition benches.

That opposition was divided. While there had been some speculation the Liberals and United Farmers could join together to fight the Conservatives, it never happened. Instead, the United Farmers dissolved to form the Progressive Party under Manning Doherty, but even that attempt at renewal faltered when some MLAs decided to keep sitting under the United Farmer label.

Things got worse when Doherty stepped aside to run for the federal Conservatives and was replaced by W.E. Raney, someone who was no better placed to keep the sputtering movement together.

The Liberals, under W.E.N. Sinclair, were similarly weak. Like the Progressives, Sinclair was a staunch prohibitionist and “a throwback to the dour Presbyterian Grits of nineteenth-century Ontario”, according to historian Peter Oliver.

Sinclair’s position on prohibition went against the views of one of the Liberals’ key constituencies: Franco-Ontarians. But the Liberals could have still kept these voters onside had they opposed Regulation 17, a law that limited French-language education in the province. Instead, Sinclair spurned them and gave Franco-Ontarians little reason to back the Liberals — and some of his MLAs decided to run as Independent Liberals in their eastern Ontario ridings to give themselves a better chance.

The Liberals weren’t the only ones being divided, though, as when Ferguson called the election he lost his attorney-general, W.F. Nickle, who resigned in protest. He would be joined by a number of Conservative party officers, workers and candidates. But the election was on, and set for December 1.

Ferguson also faced opposition from many corners: the Toronto Star, the Protestant churches and from both the Liberals and Progressives.

But he soon quelled the discontent within his party by putting a little water in his anti-prohibition wine. The proposal was always going to require liquor permits and allow dry counties to remain dry if they wanted to, but now “beer by the glass” would no longer be an option: there would be no return of the beer halls.

Though repeal would help fill the government’s coffers, Ferguson mostly argued for it due to the failure of the Ontario Temperance Act. Alcohol consumption was still high, based on the number of prescriptions doctors were handing out and the popularity of home brewing — and bootlegging.

Using the new-fangled radio, Ferguson took the case to the people, explaining that enforcing the OTA was costing more than the enforcement of all of Ontario’s other laws, to little effect. Government control of the liquor trade would be better for everyone.

Though prohibition was very popular in some quarters, the opposition parties were too weak and divided to make their case. Neither the Liberals nor the Progressives ran full slates, meaning no single party was running in enough ridings to provide a serious alternative to the Conservatives.

The result was a resounding victory for Ferguson. The Conservatives won 72 seats and over 55% of the vote, with the Liberals (of various hyphenated labels) taking 23 seats with 24% of ballots cast and the Progressives and United Farmers combining for 14 seats and 8.5% of the vote. Candidates running under a “Prohibitionist” banner also captured 8.5% of the vote.

Ferguson would have one more victorious election under his belt in 1929. The Conservatives (under his successor, George S. Henry) would be booted from office in 1934, along with many other Depression-era governments.

But the legacy of the 1926 Ontario election can still be seen throughout the province even today. With the repeal of the OTA, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, better known as the LCBO, was founded in 1927.

1942 Ontario CCF leadership

The Ontario CCF’s first leader

April 3, 1942

As the Second World War raged across Europe, North Africa and the Pacific, Canadians sensed that things would not go back to where they were before the war had started — assuming the Allies could win, of course. The trauma of the Great Depression and the demands of the war demonstrated to Canadians that there was a need for a more activist central government, one that would ensure the well-being of everyone. If the government could mobilize massive resources to defeat enemies overseas, why couldn’t it do the same to guarantee a minimum standard of living at home?

This was the moment that the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation had been waiting for, and accordingly the CCF started to surge in some of the first political polls ever conducted in Canada.

Already established in Western Canada, the CCF was having difficulty breaking through in Ontario. But a byelection in the riding of York South provided an opportunity for the party.

The Conservatives had yet to recover from the defeat of R.B. Bennett’s government in 1935. His replacement as leader, Robert Manion, had no success in the 1940 election and the Conservatives went back to the drawing board. Rather than look forward, however, the Conservatives looked back and acclaimed Arthur Meighen, leader and briefly prime minister during the 1920s, as their party chief in 1941.

Assailed on his war record, Mackenzie King was desperate to see his old and hated foe go down to defeat. When a byelection was called in the riding of York South to get Meighen into the House of Commons, the Liberals opted not to run a candidate. To avoid splitting the vote, they left the field open to Joseph Noseworthy, the seemingly long-shot candidate of the CCF.

With a little help from the federal Liberals — though not the provincial Liberals, whose leader, Premier Mitchell Hepburn, backed Meighen — Noseworthy scored an upset victory in February 1942. It spelled the end of Meighen’s comeback attempt, but also created some positive momentum for the Ontario CCF.

The Ontario CCF wasn’t in the best of shape. In the last provincial election in 1937, the party had failed to elect a single candidate and took just 5% of the vote. But with support for the national party rising and fresh off the stunning win in York South, it was decided that the Ontario CCF needed to get better organized. To mark the 10th anniversary of its founding convention, the Ontario CCF decided they would finally name something they hadn’t yet had: a party leader.

A convention was set for April 1942, where the party would decide on platform policy and name its new leader. A total of 17 candidates were nominated for the post, including Noseworthy, future federal NDP leader David Lewis, then-sitting Ontario CCF president Sam Lawrence and Agnes Macphail, the first woman ever elected to the House of Commons.

In the end, all but two declined the nominations. One was Murray Cotterill, the 28-year-old secretary to the Toronto labour council and a stalwart of the CCF Youth Movement.

The other was Edward (Ted) Jolliffe, the vice-president of the provincial council of the CCF. “Tall and slender,” according to media reports, Jolliffe was born in China while his Christian missionary parents were in the country. Also young at just 33, Jolliffe nevertheless had an impressive resume. He had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford (where he had founded an Oxford branch of the CCF with David Lewis), a journalist and a lawyer, and had twice stood as a candidate for the federal CCF.

Between the two, it wasn’t much of a contest. The delegates gathered at the Carls-Rite Hotel in Toronto, more than 100 strong, and overwhelmingly selected Jolliffe as the first leader of the Ontario CCF. The detailed results were not announced, but “it was learned reliably, however, that the majority was so sweeping as to show almost complete endorsation by the 107 delegates” according to the Canadian Press.

In his victory speech, Jolliffe attacked the Hepburn government, both on the premier’s unpatriotic position on the war effort (he had dismissed the U.S. Navy and predicted that the Soviet Union would be defeated) and his unwillingness to create a social safety net for Ontarians.

“We believe the C.C.F. has the policy and the C.C.F. is the only hope in this province,” he said, citing a previous meeting he had with Hepburn where the fate of those on unemployment relief was discussed. “There was contempt and hatred in his tone of voice,” Jolliffe charged, “hatred and contempt for the unemployed.”

“The time has come, following C.C.F. successes in other provinces and in the federal field, to open a ‘second front’ here in Ontario. And with the help of the workers and the farmers we are going to do it.”

Jolliffe would deliver on his pledge. Before the convention, one of its organizers had confidently predicted that the Ontario CCF could elect 15 candidates in the next election. When it was finally called in 1943, the CCF won 34 seats and formed the official opposition. One of those seats was Ted Jolliffe’s. He ran, and won, in York South.

1943 Ontario election

The Big Blue Machine revs up

August 4, 1943

Wars are transformative moments in history, and the Ontario election of 1943, taking place just as the tide of the Second World War was turning in the Allies’ favour, was a transformative moment for Ontario.

Not only did the election gave birth to a new political dynasty, it also inaugurated a new party system that has survived in Ontario to this day.

Even before the war started, Ontario had been going through a period of turmoil. The Great Depression had impacted the province like everywhere else, and helped bring to power the charismatic (and some would say demagogic) Mitchell Hepburn, a populist with a volatile personality — and a colourful personal life. Though a Liberal premier, Hepburn would quickly become the nemesis of Liberal prime minister Mackenzie King.

After initially working together once Hepburn had come to power, the two would eventually come to hate each other. Hepburn felt that King interfered too much in his bailiwick. The paranoid King saw in Hepburn a rival who was continually trying to bring him down and take his spot at the head of the Liberal Party and the country.

When Hepburn joined Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis in criticizing King’s prosecution of the war effort, the prime minister pulled out all the stops to defeat Duplessis in the 1939 Quebec election and subsequently took his own national victory in 1940 as a rebuke of Hepburn’s attacks.

Eventually, Hepburn’s erratic and hard-living style was impacting his leadership of the Ontario Liberals as well as his own health, and he stepped down as premier in 1942 (though he stayed on as the provincial treasurer). By then, though, Hepburn had almost gone entirely over to the other side, campaigning with federal Conservative leader Arthur Meighen in the York South byelection (which Meighen lost) and saying he would vote for John Bracken, Meighen’s replacement as leader, in the next federal campaign. When Hepburn likened King’s political tactics to Adolf Hitler’s, the Ontario Liberals had finally had enough and Gordon Conant, Hepburn’s ally and choice as interim successor, removed Hepburn from cabinet.

As the date for the Liberal leadership approached, the divisions within the Liberal Party were coming to a head. Conant, claiming nervous exhaustion, removed himself from contention and checked himself into a hospital. Delegates chose Harry Nixon, who had brought the remnants of the old United Farmers and Progressives into the Liberal Party in the 1930s, as the new leader and premier of the province.

Nixon had King’s support, and the prime minister saw in his victory a deliverance from the Hepburn menace, a “remarkable evidence of the moral forces that work in the unseen realm, and of the vindication of right in the end.” King also advised that Nixon go to the polls as soon as possible, and Nixon called an election shortly after he was sworn in as premier.

But Nixon’s decisive leadership victory did not heal the divides within the Liberal Party, and the organizational links between the provincial and federal wings had been severed. Hepburn wouldn’t go away either, and he ran as an Independent Liberal in his Elgin riding.

While the Liberals were tearing themselves apart, the Conservative opposition was getting its act together. Now under the leadership of First World War veteran George Drew and re-branded the Progressive Conservative Party (Bracken, a Progressive premier in Manitoba, had accepted the national leadership of the party on the condition that the name be changed), the Tories had developed a progressive 22-point policy platform and strengthened their local organizations across the province.

Also stacked against Nixon and the Liberals was the rising Co-operative Commonwealth Federation under Ted Jolliffe. Though the Ontario CCF had been shutout in the 1937 election, the war saw a rise in CCF support across the country. National polling was beginning to put the socialists in contention and its prospects for forming government in places like British Columbia and Saskatchewan were looking up. Labour was uniting behind the CCF and Jolliffe was an effective, articulate leader, pitching a future vision of the province that would deliver a better life for workers, soldiers and their families after the war was over.

Polls before the campaign had put the CCF in third, but by election day the latest numbers from the nascent Gallup Poll had the CCF ahead, with 36% support to 33% for Drew’s PCs and 31% for the Liberals.

The competitive contest pushed the Liberals to try to lump the PCs and the CCF together, seeing in Drew’s progressive platform yet more socialism that only a Liberal government could keep at bay. But the PCs were just as opposed to the rise of the CCF — Drew would campaign hard against the ‘Red Menace’ once in power — and his allies went to bat against the socialists, claiming that the CCF would break Canada’s connection to the British monarchy. One third-party ad charged that “The C.C.F. Would Get Rid of Churchill” and begged Ontarians to “Keep Ontario British”.

The Liberals were facing pressure from both ends — and also had to grapple with the unpopularity of the Mackenzie King government. King had just held a plebiscite on conscription that divided English and French Canada (again) and was still refusing to send conscripts overseas, so the Tories cast Nixon as King’s puppet, and King’s government as beholden to Quebec. “The voice may be the voice of Nixon,” Drew said, “but the words will be the words of Mackenzie King.”

Citing the requirements of the war, the teetotaler King had also instituted a reduction in the supply of beer in the country, sparking an uproar among Canadians who were willing to give up a lot for the war effort — except a drink. It wasn’t prohibition, but the result was that the beer halls would run out of supply before the end of a hot summer’s day, when labourers and farmers were thirsting for a cool beer after a long day’s work under the sun. The Liberals were doomed.

Still, the outcome of the election was in doubt. Every leader claimed they were on track for victory, but an editorial in the Ottawa Evening Citizen summed it up best: “stalemate seems probable,” the editorialists wrote, “yet so unpredictable are elections under present circumstances that almost anything can happen.”

The result showed a divided province. Drew and the Progressive Conservatives won 38 seats, an increase of 15 since the 1937 election, but saw their share of the vote drop 3.6 points to 35.8%. They suffered losses to the CCF, but also made gains in the southwestern portion of the province that had long been the Liberal heartland, and where the Tories had been shutout in 1937.

The CCF captured 31.6% of the vote, a gain of 26 points since the last election. The party won 34 seats, sweeping northern Ontario, making significant gains in Toronto and winning seats in the industrial centres of Windsor, Hamilton and Kitchener. Two Communists were also elected (A.A. MacLeod and J.B. Salsberg) in Toronto under the Labour-Progressive banner, as the Communist Party had been banned in 1940.

Support for the Liberals collapsed, dropping 19 points to just 30% and leaving the party with only 15 seats — 16 seats if Hepburn, elected as an Independent Liberal, is added to the total. The Liberals had retained their support among Franco-Ontarians and in parts of the southwest, but they had been dealt a serious blow.

“In my inner nature,” King wrote in his diary after the results of the election were known, “I feel a sense of relief that a cabinet that has been so unprincipled and devoid of character has been swept out of Queen’s Park.”

The Liberals had indeed been beaten, but Hepburn wasn’t done just yet. He’d return as leader once again after Nixon’s resignation. But the 1945 election would not see the return of the Liberals to power. Instead, Drew and the Progressive Conservatives would secure a majority government — and the Big Blue Machine would continue powering Ontario until 1985. The CCF had come close in 1943 and would whither under Drew’s ferocious attacks in 1945, but it formed the official opposition again in 1948 and on several more occasions as the Ontario New Democrats, who themselves would form a government in 1990.

The 1943 election had brought the Conservatives back to power, where they would remain for decades. But it also brought about a new dynamic in Ontario politics that has stood the test of time.

1947 Ontario Liberal leadership

How do you follow Mitch Hepburn?

May 16, 1947

The early 1940s were a tumultuous time in Ontario politics. Liberal premier Mitch Hepburn was a magnet for controversy, and after his own party turned on him — both those governing in Toronto and Ottawa — he stepped down, his party was turfed in the 1943 election, the PCs under George Drew came to power and the CCF formed the official opposition.

Back as leader for the 1945 election for one more kick at the can, Hepburn was beaten when Drew led his PCs to a big majority government. The Liberals were only able to tread water and hold their seats, but the collapse of the CCF meant the Liberals were back in the official opposition role — though without Hepburn.

He had failed to win his own seat, and so the Ontario Liberal Party turned to Farquhar Oliver to hold down the fort.

First elected as a United Farmer in 1926, Oliver was the last of the UFOs when he joined the Liberals and Hepburn’s cabinet in 1941. It was an arrangement that didn’t quite work out, as Oliver quit the following year before re-joining when Hepburn stepped aside. But, two elections later and with the Liberals lacking a leader at Queen’s Park, it was Oliver who took over on an interim basis.

Only 43, Oliver was still an experienced member of the Liberal caucus, even if he wasn’t much loved. An editorial in The Globe and Mail said that “even his warmest admirers would not claim for him that he has shown the vigor, the abilities and the industry of the great figures who led the Ontario Liberals in the past.”

Perhaps that’s why he had to campaign for his own job when the Ontario Liberals held a leadership convention in 1947.

His opponents on the ballot included Colin Campbell, a former MPP from Sault Ste. Marie and a cabinet minister in Hepburn’s government who threw his name into the ring at the last minute, and city councilor and former Toronto MPP Allan Lamport.

Alvin Cadeau of Burlington and W.A. Gunn of Toronto were also in the running.

But as the incumbent, Oliver was the favourite. At least, he was the favourite to win the leadership. Rumour had it that the meddling Liberals in Ottawa, particularly those around the powerful federal minister C.D. Howe, preferred Campbell, who had started his political career as an MP.

About 1,200 delegates attended the party’s convention at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel on May 15 and 16, 1947, making it the party’s biggest convention up to then.

Each of the candidates gave a speech, but the reviews awarded Oliver as the victor for his “fighting address”.

“Don’t worry that I won’t be aggressive. Don’t think I won’t fight. Drew is ready to be punctured and the time to puncture his balloon is between now and the next election. But you don’t win elections in the two years after the last one; you win in the two years before the next one. That’s why I’m going to organize this province from end to end.”

He pledged to keep the Ontario Liberals in the middle road between the “reaction of Toryism and the wild ideas of socialism”, and it was widely seen that his speech secured the leadership for himself and deflated Campbell’s upstart campaign.

The detailed results of the vote were not announced, only that Oliver won “by a substantial overall majority”. Knowing he was beaten handily, Campbell successfully moved to make Oliver’s victory unanimous.

Farquhar Oliver would lead the Liberals into the next election in 1948, but rather than puncture Drew’s balloon he found himself back in third place when the CCF surged ahead. He resigned in 1950 but would be re-installed as leader before the decade was out, and he would again add his name to the long list of Ontario Liberals who could not get themselves into the premier’s office for the four decades between 1943 and 1985.

1949 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership

The rise of Old Man Ontario

April 27, 1949

When the Ontario Progressive Conservatives under George Drew won the 1948 provincial election, there was just one problem: Drew, the premier, had failed to win his own seat.

Except, it wasn’t really much of a problem for George Drew.

Already eyeing bigger and better things, Drew decided not to try to get himself a seat at Queen’s Park through a byelection. Instead, he’d run to take over the national Progressive Conservative Party. So, just a few months after asking Ontarians for a new mandate to govern in June, he contested and won the federal PC leadership in October. Only after securing that job did he resign the premiership.

It meant the Ontario PC leadership was race was on. First out of the gate was Leslie Blackwell, an MPP from Eglinton and the attorney general. Hoping to get the contest over with and a new premier in place as soon as possible, Blackwell pushed for an early vote before the end of 1948.

Instead, Drew (who had quarrelled with Blackwell) recommended the appointment of Thomas L. Kennedy as his interim replacement and the party settled on April 27, 1949 to name the next permanent leader of the Ontario PCs.

Kelso Roberts, a former Toronto MPP who hailed from northern Ontario, also declared his candidacy but it wasn’t until after the legislature was prorogued just a few weeks before the leadership vote was held that two other candidates came forward.

The first was the suave, urbane Dana Porter, a Toronto MPP since 1943 and a cabinet minister.

Next was Leslie Frost. A veteran of the First World War (like Blackwell), Frost had been an MPP since 1937 for the riding of Victoria, based around the town of Lindsay.

Treasurer (today’s finance minister) in the Drew government, Frost was described by the Telegram as “the most tranquil man in the Ontario legislature.” Frequently leading the government as the septuagenarian Kennedy was often absent from Queen’s Park, Frost had considered retirement rather than running for leader. But in the end he announced on April 12, 1949 that he’d be a candidate and got a small leadership campaign organization up and running. His campaign would eventually spend less than $3,000.

With the imaginative slogan of “Frost for Leader”, his political brochure boasted that “he has never allowed his public responsibilities to completely detach him from living the simple country life which he has always lead [sic]. He enjoys his hobbies of fishing and hunting but his greatest hobby is ‘people’.”

Frost’s “country life” was a cornerstone of his leadership campaign. He had the advantage of being from somewhere other than Toronto, the city which Blackwell, Roberts and Porter were all identified with either because they represented ridings in Toronto or had grown up there. Frost’s rural background gave him an edge over the others.

On Monday, April 25 some 3,000 delegates, alternates and other attendees (including about 350 women) gathered at the Royal York Hotel to pick the party’s next leader and the province’s next premier. The convention was based out of the main ballroom of the hotel.

Booths for all the candidates, each bedecked with a blown-up photograph of its man, had been set up around the room as focal points dispensing literature, buttons and sound advice. Large signs urging support for the contestants covered the walls, and placards were propped up in every corner. A troubadour strolled around the hotel strumming a guitar and singing the praises of Dana Porter. The Frost Committee had engaged three pipers and a drummer, who strode through the lobby, the ballroom, and other public areas emitting sounds that would have warmed the blood of their man’s Scottish grandfather.

Each of the candidates hosted delegates in their hotel suites. Porter even entertained them there with a female accordionist.

The focal point of the convention would be the speeches. Drew returned to warn the crowd of the dangers of international communism, the sort of Red-baiting speech common to the strain of Drew PCs. Then, each of the candidates had 15 minutes to make their pitches.

These speeches were all greeted by the requisite enthusiasm of their supporters in the hall, but none were particularly memorable. They might not have changed many of the contours of the contest. Porter wasn’t seen as a serious contender and Roberts had the disadvantage of being seatless (and was greeted with booes when he disagreed with a piece of government policy in his speech). The race was widely seen as between Blackwell and Frost, with Blackwell recognized as the riskier, less predictable option than Frost and his bland reliability.

Though Frost might have been the favourite, the outcome was in some doubt. Observers expected it to go at least two rounds. Instead, the delegates in the “steaming-hot hall” gave Frost a smashing first-ballot victory.

Though the results were not officially announced, reports gave Frost 834 votes (57%) against only 442 (30%) for Blackwell. Roberts and Porter were well back with 121 and 65 votes, respectively.

The crowd, which might have expected a longer afternoon of voting, cheered Frost’s victory, and pipers and supporters streamed into the hall in celebration. Blackwell moved to have Frost’s victory be made unanimous, and so it was.

When Frost was sworn in as premier, he kept the treasury portfolio to himself and would wait until November 1951 before he sought his own electoral mandate. He got it, and would go on to win two more elections in 1955 and 1959 before stepping aside in 1961.

Despite only being 53 when he won the PC leadership, his unflashy style would earn him the nickname “Old Man Ontario”. Frost continued and solidified the centrist approach of Drew, expanding the size and role of government and investing in public services and setting the stage for what would be another 24 years of Tory rule to follow his 10 years as premier.

1971 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership

Bill Davis wins, but nearly loses

February 12, 1971

Running a front runner’s campaign is often the safe play when you’re the front runner — that’s why it’s so common. But, sometimes, it nearly backfires.

In 1971, the Ontario Progressive Conservatives knew a thing or two about being front runners. They had been in power since 1943 and were in the midst of a string of seven consecutive majority governments. John Robarts, the author of the two most recent victories, nevertheless had his majority reduced in 1967 and, with nearly a decade as premier under his belt, resigned at the end of 1970.

There wasn’t much doubt who would replace him.

Bill Davis was just 41 but had already been an MPP from Peel Region since 1959. He was the minister of education at a time when the Ontario education system had seen a massive expansion. He had the support of a majority of cabinet ministers and about two-thirds of the PC caucus.

The Davis team was so convinced of their eventual win that they declined the help of some of the brightest political organizers in Tory circles, including the legendary Dalton Camp and Norman Atkins.

Stung by their rejection, the architects of the so-called “Big Blue Machine” cast about for another candidate to back and found one in Allan Lawrence.

A Toronto MPP since 1958, Lawrence had been a bit of a maverick as a backbencher. But late in the Robarts government Lawrence got a promotion to cabinet and was named the minister of mines and northern affairs. The move actually made him a potentially formidable leadership contestant. He already had a base in Toronto. To that, he was able to add support from PC members in northern Ontario, a region of the province he frequently visited as minister.

Camp, Atkins and crew helped mould Lawrence into a serious challenger for Davis. While the front runner ran a stodgy, old-fashioned campaign, Lawrence had a more modern organization.

Davis’s approach to the campaign reflected what would be his approach to being premier and party leader. He was the candidate of the “establishment”, a Red Tory that would continue in the moderate (and election-winning) ways of Leslie Frost and John Robarts. Not wanting to ruffle too many feathers, Davis was reluctant to attack his opponents or propose much in terms of policy. Not so for Lawrence, who went on the offensive against Davis’s record as education minister, criticizing what he considered the ministry’s “out of control” budget.

He wasn’t, though, the candidate of the right. That title went to Darcy McKeough, an MPP from southwestern Ontario since 1963 and minister of municipal affairs. Though only a few years younger than Davis, he was the youngest member of Robarts’s cabinet. He staked out a position on the right-wing of the party and as a unity candidate for those who couldn’t decide between Davis and Lawrence.

Also in the running were Bob Welch, minister of citizenship and MPP from the Niagara region since 1963, and Bert Lawrence (no relation to Allan), an eastern Ontario MPP and minister of financial and consumer affairs. Rounding out the list was Robert Pharand, a young single-issue candidate advocating for a fully-funded Catholic education system.

As the leadership convention approached, the certainty that Davis would win had gone. He was still the front runner, but he was up against some surprisingly strong challengers.

The convention, held at Maple Leaf Gardens, didn’t go quite as planned. New electronic voting machines were used but when the count from the first ballot was complete it was clear something had gone wrong — the numbers didn’t match the number of delegates who voted. So, it was decided that the first round results would be scrapped and it would be run again the old-fashioned way.

The delays made the leadership race a marathon and it wasn’t until the evening that the results of the first (re-run) ballot were announced.

Davis was on top, but he had just 33% of the vote. Allan Lawrence had a strong showing with 26%, followed by McKeough at 16.5% and Welch at 16%. Rounding out the list was Bert Lawrence with 8% and Pharand with under 1% of the vote.

Pharand was automatically eliminated, but Bert Lawrence also decided to throw in the towel after scoring so poorly. Neither endorsed any of the other leading candidates.

On the second ballot, Allan Lawrence emerged as the clear Anyone-but-Davis candidate. He picked up 67 votes to only 47 for Davis, shrinking the gap from seven points to six points. McKeough and Welch picked up only a handful of votes, and Welch was eliminated next. He endorsed no one.

Lawrence picked up more votes on the third ballot with an increase of 108 against 74 for Davis. The gap was now four points — 41% to 37%. McKeough, who increased to only 21%, was eliminated.

Now after midnight, it was clear this supposed coronation was anything but. Over three ballots, Davis had gained only eight percentage points against Lawrence’s 11. It would come down to that final ballot and the votes of McKeough’s supporters. McKeough would be kingmaker. And he placed the crown on Davis.

At least, that’s what he intended to do.

He nearly failed. On that final ballot, Lawrence’s support increased by 162 votes. Davis’s total increased by only 143. McKeough hadn’t delivered even a majority of his delegates to the Davis camp. But it was just enough. After 2 a.m. in the morning, the results were finally announced: 51.4% for Davis, 48.6% for Lawrence. Just 44 votes made the difference.

It could have been a divisive leadership race. While there might have been some hurt feelings in the party, McKeough, Welch and both Lawrences all ran as Ontario PC candidates in the next general election and served in Davis’s cabinet. Camp, Atkins and the rest of the Big Blue Machine kept all cylinders firing for the party’s new leader.

The result was another majority victory for the Progressive Conservatives later that year in 1971, followed by three more wins before Davis resigned in 1985 — the year the Big Blue Machine finally came to a grinding halt.

1982 Ontario NDP leadership

The Ontario NDP goes for the win

February 7, 1982

The 1981 provincial election was a traumatic one for the Ontario New Democrats.

Their future looked bright in the 1970s, as Stephen Lewis brought them to official opposition status in 1975 and helped keep the Progressive Conservatives under Bill Davis to a minority in 1977. Lewis stepped aside after that election and the party chose Michael Cassidy as his successor.

But Cassidy was no Lewis. He couldn’t match his charisma and appeal, and in the 1981 election the NDP lost over a third of its seats, dropping decisively to third-party status as the PCs regained a majority government. When Cassidy, too, stepped aside, the party came to a conclusion: in an age of image politics, they needed an interesting, electable leader at the helm.

There were two candidates who were seen as potentially fitting the bill.

One was Bob Rae. Only 33, Rae was a first-term Toronto MP making a name for himself as the NDP’s quotable finance critic in the House of Commons. Judy Steed, writing in the Globe and Mail, profiled him as the “son of a diplomat but not a rich man’s son, he has the kind of background and credentials that make him an ideal candidate. Born in Ottawa, where he went to public school, educated in Washington and Geneva, bilingual, a Rhodes scholar, a lawyer, articulate, witty, photogenic… Mr. Rae has generated an almost unprecedented enthusiasm among NDPers.”

The other was Richard Johnston. Also in his mid-30s and a former social worker, Johnston was the candidate of the left-wing of the party. An MPP for Scarborough fresh off a byelection win that won him the seat vacated by Lewis, Johnston campaigned to give more power to the grassroots of the party.

Once Rae and Johnston got into the race, other party heavyweights opted to stay out. But not Jim Foulds, a veteran MPP from northern Ontario who was the “outsider” as the sole candidate who didn’t represent a seat in the Toronto area.

According to Steed, Foulds “exudes a kind of unsophisticated warmth that may not be appreciated in downtown Toronto but goes over well in small towns and rural areas.”

It was quickly apparent that Johnston and Foulds had an uphill climb. Rae earned the support of 11 of the 21 caucus members and landed the endorsement of Donald MacDonald, leader of the Ontario CCF and NDP from 1953 to 1970, a few weeks before the convention.

It was his moderate approach, high profile and “electability” that gave Rae the advantage over his two opponents. The party had decided they wanted a winner. They weren’t choosing the next leader of the Ontario New Democrats. They thought they were potentially choosing the next Ontario premier.

There wasn’t much suspense when over 3,000 New Democrats attended the convention held at the Harbour Castle Hilton in Toronto. A questions-and-answers session on the Friday of the convention went well for Rae and Johnston was seen as having given the best speech on Saturday. But on Sunday, when a little more than 2,000 delegates would cast their ballots, it was clearly Rae’s contest to lose. Even his own staffers were privately predicting he’d prevail with over 60% of ballots cast.

It was a solid guess. Rae won handily on the first ballot, taking 65% of the vote against just 24% for Johnston and 11% for Foulds.

Rae won with the backing of the labour unions (who had votes and volunteers to provide on the convention floor), the party establishment and the moderates looking to challenge the Davis government. Johnston’s camp felt they had been treated a little unfairly in the delegate selections, but their candidate nonetheless rallied to Rae after the results were announced, as did Foulds.

“The Rae support was much stronger coming into the convention than we anticipated,” Johnston said, with one of his organizers bluntly admitting “we were out-pointed, out-gunned and out-manoeuvred.“

By the end of the year, Rae had his seat at Queen’s Park when Donald MacDonald stepped aside. Rae led the NDP to modest gains in the next election in 1985, enough to reduce the PCs, now under Frank Miller, to another minority and bring them down in conjunction with David Peterson’s Liberals. The NDP would get back to official opposition status under Rae in 1987 before he led them to the promised land in the 1990 campaign. The New Democrats who believed in 1981 that they were selecting a future Ontario premier were proven right.

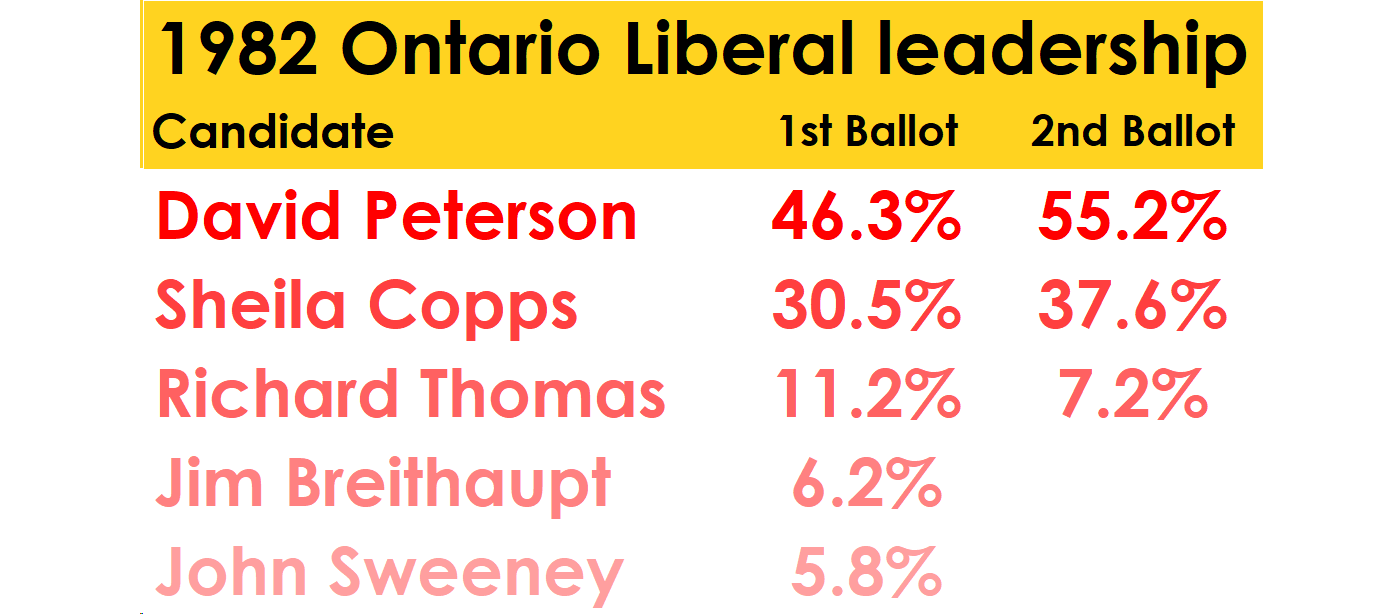

1982 Ontario Liberal leadership

Ontario Liberals opt for the ‘radical centre’

February 21, 1982

After two election results in which he was unable to make any significant gains for the Ontario Liberal Party, Stuart Smith threw in the towel as leader a few months after the 1981 election. Not only had the Liberals failed to pick up a seat in that vote, but the Progressive Conservatives under Bill Davis had upgraded the minority government they won in 1977 into a majority government.

“Intelligent and articulate,” according to Rosemary Speirs, writing in The Globe and Mail, Smith had “been unable to shake off a reputation for inconsistency and petulance that he gained in his first months as leader.”

Smith had tried to push the Ontario Liberals in a new direction. He believed that the party needed to move to the left and take votes away from the New Democrats. But the party’s traditional base in the rural southwest did not make it easy for him.

Contrary to what the Ontario Liberals have been in the 21st century, in 1981 the party was still a largely rural party with its strongest support coming from southwestern Ontario — a legacy of support dating back to the 19th century, when the Liberals dominated the southwest. Even with Smith’s attempt to move the party to the left, the Liberals still had nearly no seats in the Greater Toronto Area, where the PCs and NDP were far stronger.

When Smith announced his resignation in September 1981, it was clear who the heir apparent was. In the 1976 leadership contest, David Peterson had nearly beaten Smith, falling just 45 votes short on the final ballot. A London MPP first elected in 1975, Peterson had used the years since his leadership defeat to prepare for his next run.

For the convention that would be held between February 19-21, 1982, Peterson would have the support from a majority of the Ontario Liberal caucus, including former leader Robert Nixon. The establishment, including that of the federal Liberal Party, was behind Peterson.

His biggest challenger turned out to be a first-term MPP from Hamilton. Sheila Copps, at 29 about nine years younger than Peterson, was the daughter of a former Hamilton mayor. Seeing the field of candidates running to replace Smith, Copps put her name forward as she thought there needed to a candidate to represent the left-wing of the party. She was the ideological successor to Smith, whom she worked for before running for office in 1981.

She would turn out not to be the only candidate from the left. There was also Robert Thomas, environmental activist and a failed candidate in Parry Sound, and John Sweeney, an MPP from Kitchener. A father of 10, Sweeney wanted to restrict access to abortion but otherwise considered himself a progressive.

Jim Breithaupt, a fiscal conservative and another Kitchener MPP first elected in 1967, was considered a serious contender early on. But he was sidelined in early January when he got into a car accident that broke four of his ribs, and proxies (including his wife) had to campaign in his stead.

It was a demanding campaign, with candidates criss-crossing Ontario to meet delegates and participate in various debates and town halls (Breithaupt did the most he could speaking to delegates over the phone from his hospital bed).

But it was clear what question this race would answer: what direction did the Ontario Liberals need to take to get back to power, which they had last lost in 1943?

Peterson was the pragmatist, the unexciting moderate who focused on the economy. Copps was the progressive, focusing on social issues. She was younger and inexperienced, but she was new and interesting. Peterson had a reputation for choking. His loss in 1976 was largely credited to his convention speech, which Peterson himself later called “the worst speech in modern political history.” Would he choke again?

A few weeks out, the contest was seen as Peterson’s to lose. But to who? His campaign manager told the Globe that Breithaupt, Copps and Sweeney were all roughly tied in second for support behind Peterson, with Thomas far behind in the rear. Even a week before the convention, Peterson was still saying that Briethaupt was running third and gaining momentum.

But he wasn’t. Instead, it was Thomas. Variously described as an actor and inventor with a manner of speaking that lent itself well to the voiceover work he did, the media began to pay more attention to him as the convention approach. His pitch “that Ontario must protect its environment and that the province’s future depends on its becoming self-sufficient in energy and food,” as described by the Globe’s Paul Palango, was resonating with some members.

The convention at Toronto’s Sheraton Centre hosted over 2,000 delegates, representing some 10% of the party’s membership at the time. There was a little tension over whether Peterson could pull it off or not, but his campaign clearly had more resources than the others.

The hall was full of red-and-white “Peterson for Premier” signs and “Team Peterson” baseball caps. There was even a “Peterson ice cream wagon” for delegates to enjoy. The black and yellow campaign materials for Copps (showing her hometown Tiger-Cats pride) were less apparent, while Thomas had little more than a man in a sandwich board with “It’s time for Thomas” written on the front and “It’s time to win” on the back.

It was a packed convention with long lines for registration. Perhaps signalling the impatience of the delegates, Charles Gordon, writing in the Ottawa Citizen, noted how “the first spontaneous applause of the convention was for the mayor of Toronto, when he said his speech would be short.”

But when the results of the first ballot were announced, there was little doubt that Peterson was going to win. He took 46% of delegates’ votes on the first ballot, at the higher end of pre-convention predictions. Copps performed well with 30.5%, with Thomas finishing in third place with 11%. Breithaupt and Sweeney finished well back with 6% apiece. Sweeney, narrowly finishing last, was eliminated, but Breithaupt also withdrew after the first ballot. Neither endorsed another candidate.

The expectation was the Breithaupt’s delegates would go to Peterson and Sweeney’s to Copps. That’s likely what happened, but Peterson also picked up support from Sweeney’s and/or Thomas’s delegates — he gained 170 votes on the second ballot against 138 for Copps, while Thomas dropped by 86. Breithaupt had only 130 delegates backing him, so Peterson had to get some votes from elsewhere.

In the end, the Ontario Liberals might have decided they were sick of losing. Rather than stake out a position on the progressive left, it was smarter to stick to the electable centre.

In his victory speech, Peterson pledged that he’d keep the party in the “vibrant middle, the radical centre, call it what you will”.

Post-convention analyses echoed some concerns from Liberals, though, that by sticking to the centre the Liberals were at risk of getting squeezed. The Davis PCs were Red Tories who very comfortable in occupying the middle ground, while the New Democrats, now under Bob Rae, were also moving towards the centre. What would be left for the Peterson Liberals?

The concerns might have had some merit — until the retirement of Bill Davis changed the equation. Bucking their moderate traditions, the PCs opted for Frank Miller, a conservative more in the mould of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher than Bill Davis or Leslie Frost. By moving to the right, the PCs opened up some ground in the centre. Peterson and the Liberals took up that space and, in 1985, their long wait for a return to power finally came to an end.

1985 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership

Frank Miller wins

January 26, 1985

You know those dynasties in Alberta? Well, Ontario had one, too. When Marty McFly was travelling through time in the DeLorean, the Ontario PCs were celebrating 42 years in office and 12 consecutive election victories running through the premierships of George Drew, Leslie Frost, John Robarts and Bill Davis.

The PCs had faltered a little in two elections in the 1970s when they only secured minority governments, but the Big Blue Machine was still a formidable one by 1985, and surely was on track for many more decades of success.

When Davis resigned in 1985, the leadership race to replace him came down to four contestants. There was Larry Grossman and Roy McMurtry, two cabinet ministers from the moderate Red Tory wing of the party, and Dennis Timbrell, another cabinet minister who would be more of a centrist. Their pitch was to continue Davis’s successful running of the party in the centre of Ontario’s political spectrum.

Then there was Frank Miller, a more traditional conservative with a rural base of support. At stake was whether the Ontario PCs would turn to the right or stay in the middle.

At the delegated convention in Toronto, Miller placed on top of the first ballot with about 30% support, followed closely by Timbrell at 25%, Grossman at 22% and McMurtry at 18%.

On the second ballot, after McMurtry threw his support to Grossman, Miller was still in front. Though Grossman had gotten more of the liberated vote than Timbrell, Miller got just as much and led with 39% to 31% for Grossman and 30% for Timbrell.

On the final ballot, Grossman was able to gather nearly three-fifths of Timbrell’s vote, but Miller got just enough of it to win with 52% of the delegates’ support. The party would move to the right, a move that would divide it.

The result? Miller’s PCs managed to win only 52 seats in the 1985 provincial election, only four more than the Liberals under David Peterson (who won more of the vote). Miller’s PCs were tossed aside as the Liberals formed government with the backing of Bob Rae’s New Democrats, and the long dynasty of the Big Blue Machine was over.

1985 Ontario election

The Big Blue Machine breaks down

May 2, 1985

In 1985, the Progressive Conservative hold on Ontario looked as safe and secure as it always had been. The party had governed without interruption since 1943 and still held a big lead in the polls.

There had been a change at the top, though, after Bill Davis announced his resignation at the end of 1984. His replacement, named in January, was Frank Miller. He had won the 1985 PC leadership as a right-winger, beating several moderate candidates.

It was a risky choice by PC party delegates. While Miller tried to present a more centrist face than he had shown as a cabinet minister, he was still going to take the party away from the middle ground that had worked so well for the PCs under premiers George Drew, Leslie Frost, John Robarts and Bill Davis.

With polls showing PC support at 55% and the opposition Liberals and New Democrats tied in second with just 21%, Miller waited less than two months after his swearing in to call an election.

On the surface, things looked good for the PCs. Brian Mulroney’s federal PCs had won a landslide majority government just a few months earlier and nowhere in Canada did the Liberals run a provincial government.

The Ontario Liberals would be heading into the campaign under David Peterson, who had taken over as Liberal leader in 1982. A 41-year-old lawyer, Peterson hadn’t impressed during his short time as opposition leader at Queen’s Park but he would prove to be an effective campaigner, moving his party into the centrist territory that had been abandoned by Miller’s shift to the right.

Peterson also used his relative youth to his advantage, pegging Miller (57) and the PCs as part of the past.

“Frank Miller is fighting for Frank Miller’s Ontario,” he said in a stump speech, “a dusty dream of some 20 years ago.”

The leader of the NDP was even younger than Peterson and, like his two opponents, also heading into his first campaign. Bob Rae had even been named Ontario NDP leader the same month as Peterson in 1982 and there were hopes that Rae could take the New Democrats back to official opposition status, a role they had held in the 1970s.

However, Rae’s campaign would fail to take off. It revolved around issues, such as fighting pollution, and was unable to impose itself on the campaign when the Liberals got off to a good start. Peterson was talking about a lot of the same things as Rae, and so the NDP was crowded out of the centre-left field they had previously occupied by themselves.

While Peterson’s campaign was slick and open to the media, Miller largely avoided the press. He turned down a leaders debate. His campaign lacked energy and cohesiveness, as the leadership race had left scars within the PC Party that went unhealed.

Miller centred his campaign around a business-oriented plan called Enterprise Ontario, which contrasted with the campaigns being run by the Liberals and New Democrats that focused on social issues and unemployment. The PCs also stumbled over a promise to give Catholic high schools full funding — a controversial issue not because the other parties opposed it (they didn’t) but because it upset the PCs’ own rural and largely non-Catholic base.

(John Tory, who was involved in the Miller campaign, did not appear to learn the lesson when he ran a losing PC campaign promising funding to faith-based schools in 2007.)

As election day approached, the polls suggested that the PCs were falling back to the advantage of the Liberals, who were also buoyed by late campaign endorsements by not only the Toronto Star but the Globe and Mail as well.

The results showed the Liberals had closed the gap — but not by enough. The PCs still emerged with more seats at 52. But that was a drop of 18 seats from the previous election and cost the party a few cabinet ministers, including the likes of Morley Kells, Gordon Walker and John Williams, ministers who were “prominent members of the party’s right wing.”

While the PCs won the most seats, they took less of the vote, finishing with 37.1%, a drop of seven percentage points from the 1981 Ontario election.

The Liberals were just four seats back, gaining 14 to end with 48. The party was also up four percentage points to 37.9% support.

The Liberals made gains in the urban areas that the PCs had previously dominated, picking up seven PC seats in Toronto and three in the Peel and York region, along with four in southwestern Ontario.

According to campaign manager Ross MacGregor, the PCs “left room for David Peterson and the Liberal party to occupy the centre — and it was that centre of the political spectrum that we had so desperately tried to occupy during the Davis years without success. Peterson has succeeded in putting an urban face on the party without abandoning the True Grit rural constituency.”

The New Democrats made gains of their own, but they were far from their goal of official opposition. The party picked up four seats and 2.5 percentage points, winning 25 seats and 23.6% of the vote.

It all meant a minority legislature — and the PCs were technically still in the driver’s seat. They had governed with minorities before, and Miller wanted to try again.

But the Liberals and NDP knew this was their chance, and the two parties came together to sign an agreement that would put David Peterson in the premier’s office and ensure no election would be called for another two years, in exchange for Liberal support for NDP policies.

A four-page document outlined the terms, which included introducing a freedom of information bill, a committee to investigate patronage, election-finance reforms, and television in the legislature; broadening the powers of the provincial auditor; allowing public servants to participate in political activity; and investigating the commercialization of health services.

Miller tried to hang on, presenting a throne speech with some nods toward the Liberal and NDP platforms. But he had few kind words to say about his opponents, charging that the New Democrats were “prostituting themselves for power” and that Ontarians “deserve better than a puppet Liberal premier with the NDP pulling the strings.”

The 42-year dynasty of the Big Blue Machine came to an end when Rae presented a non-confidence motion and the government was defeated. Rather than send the province into another election, the lieutenant-governor handed the reins over to Peterson. He’d govern for five years that included a big majority victory in 1987, but his government would fall, too, though this time at the hands of Bob Rae’s New Democrats in 1990.

1990 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership

Ontario PCs choose third leader in five years

May 12, 1990

After over four decades of uninterrupted rule, the Ontario Progressive Conservatives were having a rough time in the late 1980s. The party, under new leader Frank Miller, was ousted by the Liberals and New Democrats following the 1985 election and, two years later, Larry Grossman did much worse, as the PCs dropped to third place with just 16 seats and less than 25% of the vote — the worst result in the party’s history.

Grossman, who failed to win his own seat, resigned the leadership and it wasn’t until 1990 that the Ontario PCs decided to name his permanent replacement.

They used a new system to decide the winner, abandoning the old delegated convention to give a vote to every member. Each riding in Ontario would be given an equal weight, a system that the Ontario PCs (and the federal Conservatives) still use today.

But when the higher profile contenders decided not to run, including 1985’s third-place finisher Dennis Timbrell, who was widely seen as the favourite, the race came down to two largely unknown candidates.

Mike Harris, a former teacher and golf pro, had been the MPP for Nipissing since 1981. A backbencher, he backed Miller’s leadership bid in 1985 and was subsequently named to his short-lived cabinet.

Harris was the right-wing candidate in the race, opposing equal pay legislation and supporting the abolition of rent controls and the imposition of user fees for patients visiting their doctor.

Dianne Cunningham was the moderate Red Tory candidate. She lacked even Harris’s limited political experience, as she had won a byelection in 1988 in the riding of London North. She had the backing of some of the stalwarts of the old “Big Blue Machine”, and warned that the PCs needed to modernize along with the rest of the province — otherwise another move to the right under Harris would lead to another defeat at the polls.

It was, then, a contest between perceived electability and rock-ribbed conservative ideology.

But being a party in third place, the PC leadership campaign got little attention from the media and Harris and Cunningham had difficulty raising both money and enthusiasm.

Thomas Walkom in the Toronto Star summed it up this way:

“You may remember the Conservatives. They ran Ontario for 42 years, handing out patronage jobs, greasing the wheels, passing out the contracts. They may even run it again. And yet here they are, preparing to elect as leader one of two people most Ontarians have never heard of.”

Heading into the vote on May 12, 1990, Harris was seen as the narrow favourite. But much of the caucus was remaining on the sidelines — he had only five backers within the 17-member PC caucus. Cunningham had four.

There were 33,183 members eligible to vote, but a majority stayed on the sidelines as well. Less than 16,000 cast a ballot.

Harris emerged as the victor with about 55% of both the points awarded and the ballots cast by members, winning a majority in 81 of the province’s 130 ridings.

It was a vote for Harris’s swing to the right. And, as Cunningham predicted, it failed to resonate with voters — at least at first. Harris led the indebted PC Party into the September 1990 election and finished third again, gaining four seats but capturing just 23.5% of the vote.

Harris, though, would stay on as leader, unlike his two predecessors. And after five years of Bob Rae’s NDP government, voters in Ontario came around to Harris’s way of thinking, and he led the PCs back to power in 1995.

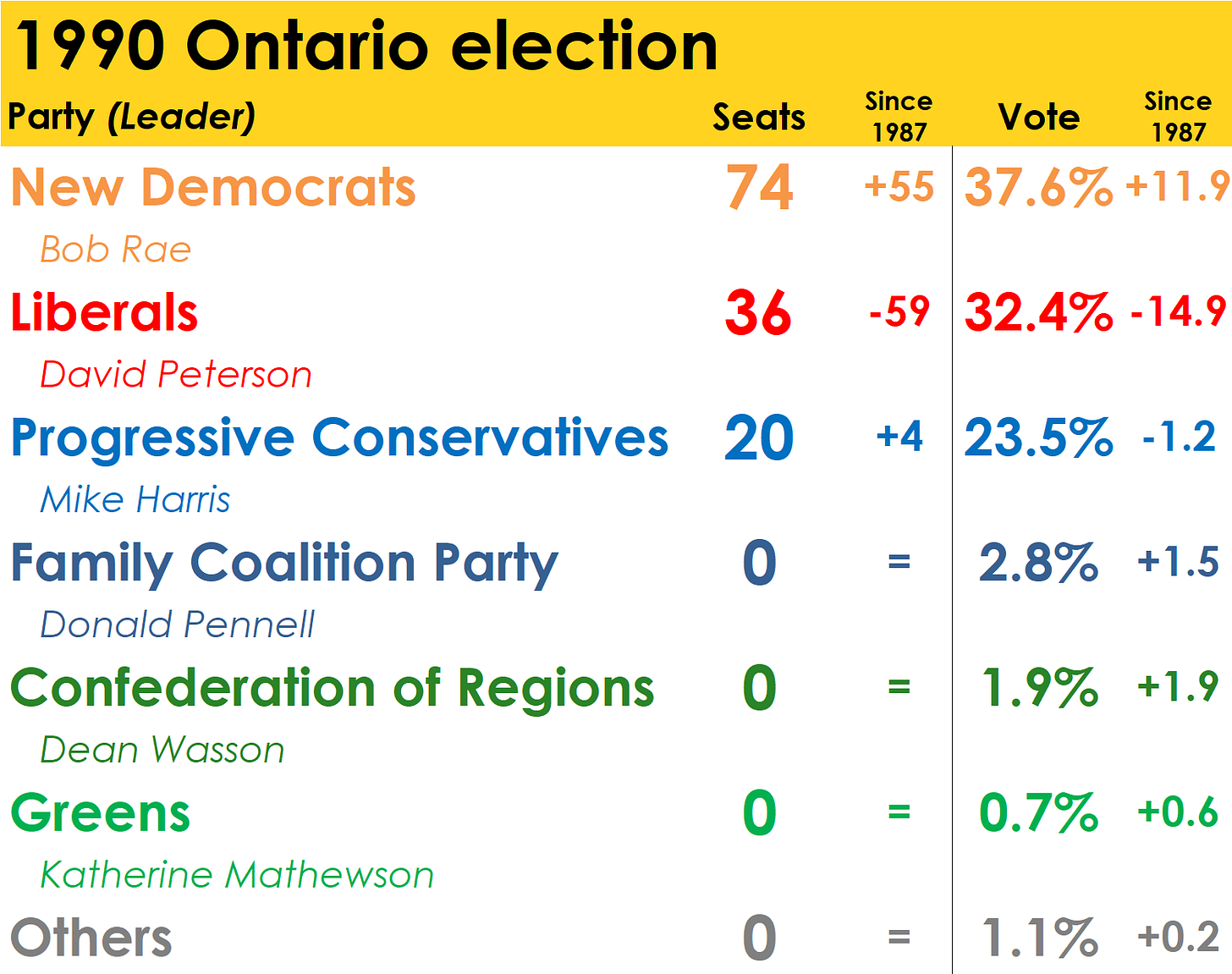

1990 Ontario election

Ontario’s Orange Wave

September 6, 1990

The 1980s were a time of political upheaval in Ontario. The long reign of the Ontario Progressive Conservatives that had begun in 1943 finally came to an end in 1985, when the Liberals under David Peterson and the New Democrats under Bob Rae combined to bring down the minority government that Frank Miller’s PCs had narrowly secured in that year’s election.

But after two years of co-operation between the Liberals and the NDP, Peterson eyed an opportunity — and won a huge majority government of his own in 1987.

Those string of successes suggested a keen political judgment on the part of Peterson, and so when the Liberals opened up a 20-point lead over the NDP in the summer of 1990, another snap election seemed like a good idea. Convention would have had the Ontario Liberals wait until 1991 or even 1992, but why pass up another sparkling opportunity?

Voters can spot a cynical political move from a mile away, though, and what seemed like a cakewalk for Peterson started off badly when the premier couldn’t quite explain the urgency for an early election call. “I don’t have to apologize for consultation with the people at this time,” he said — setting the tone for what Ontarians could expect for the next few weeks of campaigning.

Timing, of course, is everything. And the timing wasn’t particularly good for Peterson in the late summer of 1990, despite what the polls were saying.