"We have too much politics in Nova Scotia"

The 1933 Nova Scotia provincial election

This is the first article of the #EveryElectionProject, my Sisyphean attempt to write about every election that has ever taken place in Canada. With this series I hope to share with you my passion for history and explore the elections that have brought us to where we are today.

Only three elections in Nova Scotia’s history have been held in August. The third one will be on August 17, 2021. To tell the story of the first, we have to go back 88 years to 1933.

Nearly four years after the stock market collapse of October 1929, Canadians across the country were still deep in the depths of the Great Depression, a challenge that governments were proving unable or unwilling to meet. The boom times of the 1920s were over. The political upheavals of the 1930s were just getting started.

In Nova Scotia, however, the depression only prolonged what had been an enduring economic slump. Far from the bustling centres of Canadian industry, Nova Scotia didn’t experience much of the post-war boom. Its Liberal government, in power since 1882, bore the brunt of Nova Scotians’ frustrations in the provincial election of 1925.

It was a tough time to be a Nova Scotia Liberal. George Murray, premier for 26 years, had finally stepped aside in 1923 and was replaced by Ernest Armstrong. He had to take over a struggling economy whose poor prospects led Nova Scotians to leave the province to seek a better life. For those who kept toiling in the coal mines, it was a time of labour unrest.

A strike in 1925 was bungled by Armstrong but the opposition Conservatives sensed an opportunity, siding with the strikers. Gordon S. Harrington, a Conservative, was the miners’ legal advisor and helped bring the labour vote over to the Tory side.

Running on a platform of “Maritime Rights” and arguing that Nova Scotia was not getting a fair shake from the Liberal government in Ottawa, the Conservatives under Edgar Nelson Rhodes swept Armstrong’s Liberals from office in 1925, winning 40 of 43 seats in the province.

While economic difficulties, a desire for change and Rhodes’ skills as an orator might have swayed the electorate, politics in 1920s Nova Scotia was far from clean. Or sober.

“Party workers typically supplied liquor at campaign rallies and cash or bottles of liquor on election day,” writes T. Stephen Henderson in Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal.

“Chisholm, a Liberal MLA, noted that ‘people who never touched liquor at any other time would always want it at election time.’ Rum had been ‘the traditional political drink’, but many women thought it cheap and insisted on being given gin instead.”

The shift from over four decades of Liberal rule to government by the Conservatives was a significant one, and Rhodes was able to reduce Nova Scotia’s big deficit during his first years in office.

What he didn’t do, however, was successfully replicate the Liberals’ system of patronage across the province. Ensuring that the right people — Conservatives, in this case — would get the right jobs was a mainstay of 19th and early 20th century Canadian politics. But without this network of patronage in place, the Conservatives were at a disadvantage.

When Rhodes decided against enrolling Nova Scotia in Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s old age pension scheme because the province couldn’t afford its side of the bargain, the Conservatives took a hit in public support. In the 1928 election, the Conservatives were returned to power but with a significantly reduced majority government.

Change in Halifax and in Ottawa

By 1930, the Conservatives were in need of a boost. They got it with a smashing byelection win in Halifax South, the first sign that things might be heading in the right direction for Rhodes and the Conservatives.

The Liberal defeat in Halifax South spurred the departure of William Chisholm, the Liberals’ interim leader. The party would have to find a replacement — and they’d do it with the first leadership convention in their history.

The Conservatives, however, were in need of a new leader, too. After R.B. Bennett’s Conservatives won the federal election of 1930, Rhodes resigned the premiership to sit in Bennett’s cabinet. His replacement was Gordon S. Harrington.

It wasn’t clear who would be his Liberal opponent. By the time the convention was held on October 1, 1930, only two candidates had come forward: J.J. Kinley and William Duff. While they had some political experience, neither was particularly inspiring.

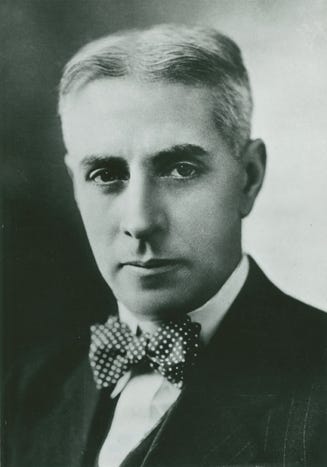

So, some Liberals looked to a 40-year-old lawyer named Angus L. Macdonald as their saviour.

A veteran of the Great War and a professor at Dalhousie University, Macdonald had never held elected office before. He had campaigned with the Liberals in 1925, but hadn’t put his name forward as a candidate until 1930, when he lost his only attempt to win the seat of Inverness in the House of Commons.

He was well-known in Liberal circles for his work at the grassroots level, setting up Young Liberal clubs across the province after the 1925 defeat. Attending the convention, Macdonald was surprised when a friend threw his name into the ring.

Not expecting this turn of events, Macdonald took the stage and initially declined the nomination. After stepping off the platform, however, he was quickly made to reconsider.

“A clutch of friends … encircled him and urged him to change his mind. Senator H.J. Logan grabbed his arm and hissed ‘don’t be a fool. This is a thing that only comes along once in a lifetime.’”

After announcing he had changed his mind, he made a strong speech and was duly chosen as the new Nova Scotia Liberal leader with nearly two-thirds of the vote.

Macdonald, however, was still without a seat in the legislature. And he would have to wait to get one.

Harrington refused to hold byelections to fill the six vacancies in the assembly, as he only had a five-seat majority and couldn’t risk losing it. Macdonald led the party from up in the gallery while A.S. MacMillan ably directed the Liberal caucus from the legislature floor (though not without issue, as he came to blows with a Conservative MLA in 1931). The new leader made use of Harrington’s refusal to call byelections by attacking him for leaving so many Nova Scotians without political representation.

Touring the province to get better known, Macdonald was shy in large crowds. But he had a warm, charming personality in small groups. According to Henderson,

“Macdonald symbolized the revitalization of the Liberal Party in Nova Scotia and, later, in Canada. He emerged from a group of young professionals who wanted to recommit the party to liberal principles. Influenced by the economic devastation of the 1920s, they were convinced that the state had a significant part to play in the economy. The dominance of ‘machine’ politicians and their corporate clients had bred a cynicism that could be removed only by sharply broadening political participation. This push for greater democracy in the province matched the rhetoric of equality common in Macdonald’s circle: their opinions mattered as much as those of the older generation.”

Macdonald disliked the way politics was done in the 1920s and 1930s. “As a matter of fact,” he said, “we have too much politics in N.S. Too much of the cheap style of politics—too much of the ward-healer—too little of the stateman—too much political so-called oratory—too little political thinking—we cannot have too much of that.”

The struggles of the Harrington Administration

Nova Scotia’s economy and public finances were already troubled by 1929. The depression could only make things worse.

Looking for sources of funds, the Conservative government set up the Nova Scotia Liquor Commission to fill provincial coffers. The end of prohibition, which voters supported in a 1929 plebiscite, proved to be a great opportunity for political parties to fill their own coffers from liquor producers and distributors.

Further afield, Harrington looked to Bennett’s new Conservative government in Ottawa for more support, but with demands coming from every province Bennett couldn’t (or wouldn’t) provide much help.

He did, however, offer to cover 75% of an old age pension program. But that was not what he had campaigned on — Bennett had promised a fully-funded old age pension program. Harrington, who had echoed Bennett’s pledge, still couldn’t afford his province’s share of the cost and had to say no. As a result, the Nova Scotia Conservatives had to wear Bennett’s broken promise as their own.

Help for the mines also fell short of what was promised, when Harrington persuaded miners to accept a wage reduction on the assurance that a deal he had worked out with the federal government would lead to more orders for coal. When Canadian railways and industries didn’t put in the promised orders, the Conservatives lost the vote that Harrington had worked to earn for the party in the 1920s.

By 1933, five years after the last election, Harrington’s window for calling the next election was closing.

The election begins

Proroguing the legislature on May 17, Harrington took two more months to announce that the election would be finally held on August 22, 1933.

“Tradition is not easily upset in the Maritimes,” mused an editorial in The Globe. “Other Provinces may do as they like but Nova Scotia takes its politics in the old fashioned style—the two-party style, which all must concede has produced leaders who have served both the Province and the Dominion well ... There seems to be little evidence of a desire for additions to the few “wingers” in the field—either right or left, pale pink or real red.”

The election would primarily pit Harrington’s Conservatives against Macdonald’s Liberals in the 30 seats spread across Nova Scotia. Harrington stood for re-election in his riding of Cape Breton South, while Macdonald put his name forward in Halifax South, which the Conservatives had won in that 1930 byelection.

Only a handful of candidates from the newly-formed Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (C.C.F.) and the labour-affiliated United Front would be on the ballot.

Harrington wanted to run on the accomplishments of his government’s “progressive policy”, including, according to The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, “the establishment of a Minimum Wage for women, the inauguration of new Health and Labour Departments, the setting up of a market board for the benefit of the primary products of the Province, a revised Motor Vehicle Act, a moratorium on mortgages and their efforts to stimulate the coal industry.”

The Conservatives released their manifesto — as platforms were generally called then — on July 22. The Liberals did the same on August 2. They weren’t very different, according to Henderson.

“Both parties promised to continue relief payments and mothers’ allowances and to introduce the OAP ... Both offered free school books, though Macdonald's plan was universal through grade eight, while Harrington's targeted only needy children. Both emphasized economy and government, better marketing of natural resources, and improvement of roads, and the Liberals sketched a tentative paving program. The Conservatives broke new ground by promising to bring electricity to every home in Nova Scotia; the Liberals pledged to conduct an inquiry into Nova Scotia's economy and the effects of national policies on it.”

The two parties would fight over an electoral map that had been reduced from 38 seats (for cost-saving) to 30. They would also fight using the rules established in the Harrington government’s Franchise Act. It was a piece of legislation that might have been designed to help the Conservatives secure re-election but would instead contribute to their downfall.

The Franchise Act

The new Act opened the door to abuse of the voters lists, and the Conservatives didn’t hesitate to charge through that door, especially in Halifax. The lists drawn-up by the government were missing thousands of Liberal voters, with a post-election inquiry estimating that 45% to 65% of names were left off the preliminary lists. In some areas, Liberals had to go to court to get access to the lists to verify who was — and especially who wasn’t — on them.

The Conservatives played tricks with the lists, posting them at the last minute before a midnight deadline or inside a store just before it closed. Some lists were placed high on utility poles or hidden out of sight.

“Liberal workers,” writes Henderson, “motivated by a sense of fighting injustice, used ladders, flashlights and car headlights, working late in the night to read and copy the lists. Macdonald later boasted that his workers were able to add 4,600 names in Halifax South in three days.”

Long lines of Nova Scotians trying to add their names to the lists didn’t stop some registrars from closing up shop early or deliberately delaying things by asking elderly Nova Scotians for proof they were over the voting age of 21.

In his defense, Harrington claimed that when the Conservatives came to power the voting lists contained lots of names from Nova Scotians who happened to be dead. They were merely cleaning things up:

“When we came in we found lists that were inactive and that carried a lot of dead people and didn’t carry enough living people … Being Christians, we might think that we will see the friend again in the Great Beyond, but we do not expect to have him turn up and vote against us.”

While the Liberals might not have been angels prior to 1925, the Conservatives’ over-zealous attempts to stack the election in their favour was used to good political effect by Macdonald, who was able to present himself as the defender of democracy against the crooked Tories.

By the end of the campaign, it was clear things weren’t going well for the Conservatives. Supporters of the party tried to make hay of Macdonald’s Catholicism, raising the spectre of separate schools, but it didn’t work.

According to a report by The Canadian Press on August 20, “the eyes of political Canada are turned on Nova Scotia this week, where Tuesday’s general election promises to carry a message of hope or despair to political leaders, both Federal and Provincial, from coast to coast.”

“The campaign has been lively,” the article went on, “but confined largely to local issues such as the new Franchise Act, old-age pensions for Nova Scotia, the position of the steel and coal industries, and highway building.”

The reporter suggested that Conservatives in Ontario, Saskatchewan and Ottawa, as well as their Liberal opponents, were watching the results closely. The omens, in the end, would prove to be bad — and prescient, as the Conservatives would lose the provincial elections of 1934 in Ontario and Saskatchewan, while Bennett would be booted from office in 1935.

“Whatever the result in Nova Scotia, it is going to be a strong talking point for somebody on the hustings in other parts of Canada.”

The results

Turnout was strong on election day. In Ottawa, The Globe’s correspondent William Marchington reported that “the ‘inside’ information from Halifax early today was that the Provincial Government would be ousted by a small margin.”

That proved optimistic. Perhaps motivated by the attempts to disenfranchise them, 86% of the men and women eligible to vote did so — and punished Harrington’s Conservatives.

The casualty list in Harrington’s cabinet was long. While Harrington was re-elected by the voters of Cape Breton South, only two of the other seven cabinet ministers — Percy Chapman Black (highways) in Cumberland and Joseph MacDonald (without portfolio) in Cape Breton North — escaped defeat.

The Liberals secured 22 seats and a majority government, capturing 52.6% of ballots cast. In a two-party race, the Conservatives’ 45.9% of the vote was only enough to win them eight seats.

The United Front and C.C.F., each running only three candidates, cobbled together about 1.5% of the vote.

The Liberals regained power with a map that was similar to the one that they had won with in 1920 and in most of the elections since the turn of the century: strong results in Halifax and most of the rest of the province, with the exception of Colchester County and around Sydney.

But there were few landslide victories. Only in Halifax North and Yarmouth did the winning Liberal candidate clear 60% of the vote. In only eight of the 30 ridings did the Liberals win more than 55% of ballots cast.

But the uniform scale of their victory cleared the Conservatives out from most of the province. They won every region except Cumberland-Colchester — and that they missed out on only marginally — with their strongest showings in Halifax and the South Shore.

Gains from 1928 included three in the Valley (Annapolis, Kings and Hants), one of the two Cumberland seats, three seats in Halifax, two in Pictou, and three in Cape Breton — including Inverness.

The Conservatives dropped in every part of Nova Scotia except in Cumberland-Colchester, while the C.C.F. did considerably worse than the Labour Party did in the 1928 election. With the exception of a single candidacy in Halifax, the C.C.F. and United Front only put forward candidates in Cape Breton. Together, they secured just 7.4% of the vote there.

The reverberations of Macdonald’s victory were felt back in Ottawa. Marchington reported that Bennett’s Conservatives attributed Harrington’s defeat to “hard times and introduction of an extreme Franchise Act.”

Mackenzie King told reporters that “the poll indicates the strength of the growing tide of Liberalism which has been steadily rising in every part of Canada” and called Macdonald “one of the outstanding young Liberals of the Dominion.”

Somewhat cheekily, Marchington filed another brief column from Ottawa about the official reaction from the ruling Conservatives:

A Globe editorial the day after the election was exultant. “Mr. Macdonald,” it said, “in thrusting aside the policies of two or three decades ago as dead issues and calling for government bold enough to forget the old party lines and carry forward a vigorous program, sensed clearly the prevailing mood of Canadians.”

“The overwhelming victory he achieved proclaims that ‘Wait and See’ commends itself no more strongly as a depression policy than it did as a war policy.”

The 1933 Nova Scotia election was the first of what would prove many elections in Canada during the Great Depression that saw incumbent governments thrown out of office. Harrington would remain as Conservative leader for one more election until stepping aside — his party wouldn’t govern the province again for more than two decades.

For Macdonald, it would be the start of a long and successful political career that would take him from Halifax to Mackenzie King’s cabinet table in Ottawa during the Second World War (some saw him as the favourite to replace King as prime minister) and then back to Nova Scotia, which he would run as premier until 1954.

“The result [of the 1933 election] reflected the sins of the Conservatives more than the virtues of the Liberals,” Henderson writes. “Yet Liberals in Nova Scotia were excited about their future and especially about the new premier. He had shown himself to be articulate, passionate and popular. By the end of the campaign, he had become known affectionately throughout the province as ‘Angus L.’”

Sources:

Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal by T. Stephen Henderson.

Article excerpts from The Globe newspaper from July and August 1933, courtesy of the Library of Parliament.

Legislature of Nova Scotia, Session 1934: Election Returns.

The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs: 1933.

Election-atlas.ca by J.P. Kirby.