Weekly Writ 9/4: Will Newfoundland & Lab. follow the federal trend?

Sizing up Newfoundland & Labrador's upcoming election.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Thursday morning.

What if they held an election and no one polled it?

We might find out in Newfoundland and Labrador’s upcoming provincial election, which must be called by September 15. No public opinion poll for the province has been published in 10 months despite the change in the premier’s office from Andrew Furey to John Hogan and the fact that an election is just around the corner.

It leaves us flying a little blind when it comes to trying to figure out what is going on. But in the absence of any hard data, could the results of the April federal election give us clues?

Newfoundland and Labrador’s election years have been aligned with the federal calendar since 2011. With the exception of 2021, those provincial elections took place after the federal election, but they were all nevertheless held in the same years and within about six months of each other.

Of course, provincial and federal politics are different. Voters — particularly voters in Atlantic Canada — are able to differentiate between the two levels of government, even where the party brands and the party systems are nearly identical. But the results aren’t wholly divorced from one another. And that seems to increasingly be the case in Newfoundland and Labrador.

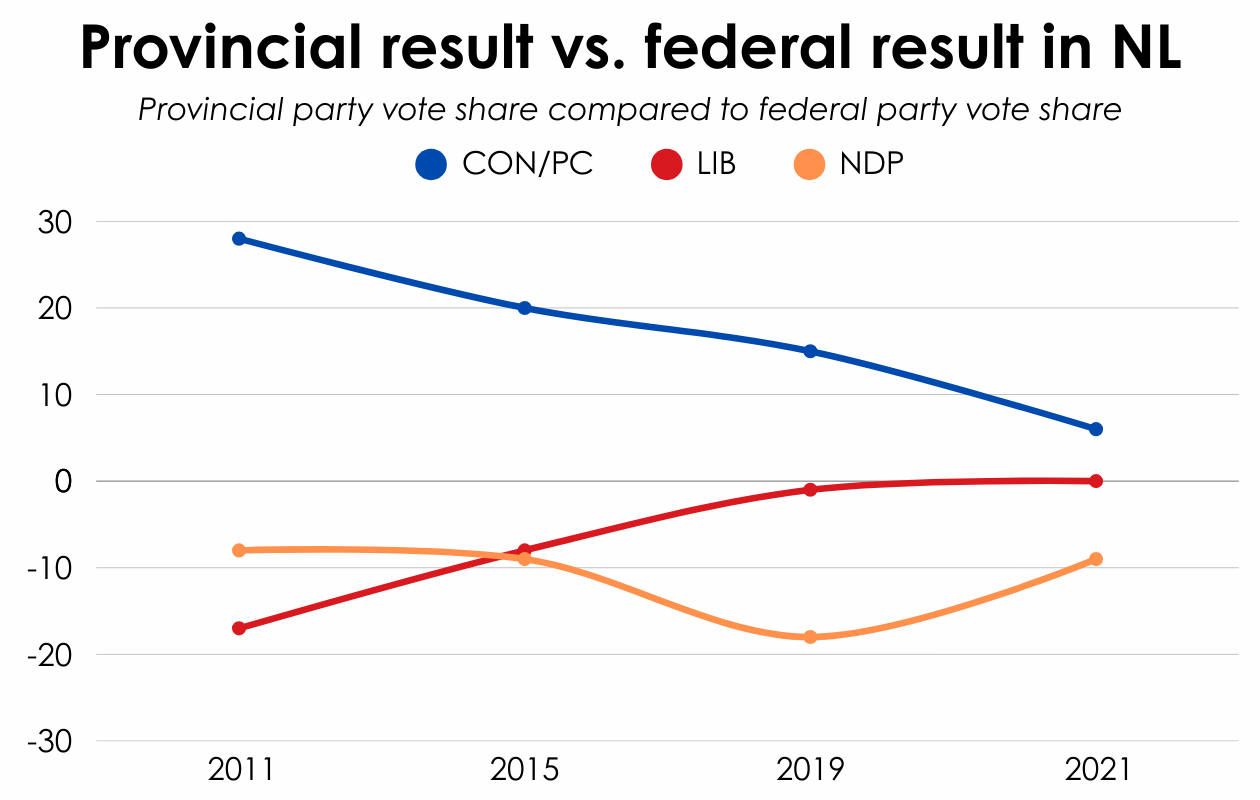

The chart below shows how provincial parties have performed relative to their federal cousins in the 2011, 2015, 2019 and 2021 elections. As the chart shows, the difference between the federal and provincial results has been getting smaller over time for the two biggest parties.

Thanks to Danny Williams’ Anybody But Conservative campaign in 2008, there used to be a significant difference between the performance of the PCs and that of the Conservatives. In 2011, Kathy Dunderdale’s PCs did 28 percentage points better than Stephen Harper’s Conservatives did in Newfoundland and Labrador. But that difference fell to 20 points in 2015, 15 points in 2019 and just six points in 2021. Over the last 15 years or so, support for the PCs and Conservatives has converged.

The provincial Liberals did 17 points worse than the federal Liberals in 2011 and eight points worse in 2015. But in both 2019 and 2021 the difference between the NL and federal Liberals was negligible — only about one point in 2019 and nearly identical in 2021.

There is a notable difference between the provincial and federal NDP, however. The provincial NDP under-performed the federal NDP by between eight and nine points in 2011, 2015 and 2021. They did 18 points worse in 2019.

What do these trends suggest about the upcoming provincial election?

It does indicate that Hogan’s Liberals should be the favourites. Mark Carney’s Liberals took 54% of the vote in the province in the April election. That gives the NL Liberals a lot of cushion. If they nearly march Carney’s performance, they will win a big majority government. They can undershoot it by 10 points and still have a good shot at winning.

The Conservatives took 40% of the vote in Newfoundland and Labrador. The PCs have tended to outperform the federal brand, so if Tony Wakeham’s PCs can do that again then they will make the election competitive.

The wildcard might be the New Democrats. Jagmeet Singh led the party to just 6% of the vote in the last election. It’ll be hard for Jim Dinn’s NDP to do much worse than that. If he improves upon Singh’s score, that vote will have to come from somewhere else.

That’s assuming that the trends we’ve seen between 2011 and 2021 are extended into 2025. While that’s a big assumption, the byelections that took place in Newfoundland and Labrador in 2024 suggest that it might not be far-fetched.

The PCs flipped two seats on the north shore of Newfoundland in Baie Verte-Green Bay and Fogo Island-Cape Freels with big gains in support at the expense of the governing Liberals. They in turn flipped one seat and retained another on the Avalon Peninsula, where the PCs weren’t able to make significant inroads.

This aligns with what happened in the federal election. The Conservatives gained between seven and 11 points in the three ridings on the island of Newfoundland outside of the Avalon Peninsula, while the Liberals dropped two points in two of the ridings and gained just one in the third. In the three ridings on the Avalon Peninsula, however, the Liberals were up between eight and 17 points while the Conservatives were only up between three and eight points. The federal Liberals holding their own in and around St. John’s while the Conservatives made inroads in the rest of Newfoundland aligns with what happened in those provincial byelections.

(It’s tougher to draw parallels in Labrador, where the election will feature a Liberal and a PC-to-NDP-to-PC floor-crosser as incumbents and two seats where the incumbent MHAs are not re-offering.)

Without any polls to guide us, this might be the best we can do as a starting point for the Newfoundland and Labrador election. The Liberals are probably the favourites, but they will need to make some gains on the Avalon Peninsula to make up for some likely losses in the rest of Newfoundland. That would present a shift in the electoral geography from the 2021 election, when the Liberals won 10 seats on the Avalon Peninsula and 11 seats in the rest of Newfoundland, while the PCs won six in each region. After the 2024 byelections, the count is now 11 seats on the Avalon Peninsula and nine in the rest of Newfoundland for the Liberals, with the PCs having five and eight seats, respectively, in the two regions. Each party’s distribution of seats between the two regions might get even more unbalanced after this campaign, but the party that maintains a greater balance will likely prevail — the winning party will probably be the one that flipped more seats in its better region while mitigating losses in its weaker one.

We’ll see if the next poll — assuming that one is coming — will tell a different story.

Now, to what is in this week’s instalment of the Weekly Writ:

News on a few federal byelections that could be added to the docket soon, plus some serious contenders are reportedly preparing bids for the NDP leadership and the Alberta Party votes to change its name.

Polls do not suggest the Liberals have lost much (if any) support this summer, plus we have new numbers out of Ontario that muddy the narrative and two polls that shed light on some wide-open municipal races in Calgary and Edmonton.

#EveryElectionProject: Brian Mulroney’s record-setting 1984 election landslide.

Upcoming milestone for Pierre Poilievre.

The first Weekly Writ of the month is free to all subscribers. If you aren’t already a paid subscriber and would like to get full access to the Weekly Writ every Thursday, please upgrade your subscription!

NEWS AND ANALYSIS

More federal byelections on the way?

According to The Globe and Mail, two Liberal MPs could be heading to Europe to take on diplomatic postings. That means they will vacate their seats and set us up for two byelections within the six months following their appointments.

The two MPs in question are Bill Blair and Jonathan Wilkinson, two heavy-weight cabinet ministers in Justin Trudeau’s government who were notably not given a seat at Mark Carney’s cabinet table. Blair could be heading to the United Kingdom, while Wilkinson could be off to Belgium or Germany.

The Globe reports that the subsequent byelections could be a way for Carney to inject some new blood into his cabinet. The short time frame, as well as the chances that Carney could have failed to win re-election, likely limited his ability to recruit star candidates ahead of the federal vote. Now, with two safe Liberal seats available and, seemingly, some stability in the House of Commons for the foreseeable future, Carney might have an easier time recruiting more of his people to replace some of Trudeau’s people.

Of course, Liberals learned in 2024 that a safe Liberal seat can prove to be not so safe after all. However, for the time being the party is not in the same situation that cost it Toronto–St. Paul’s and LaSalle–Émard–Verdun.

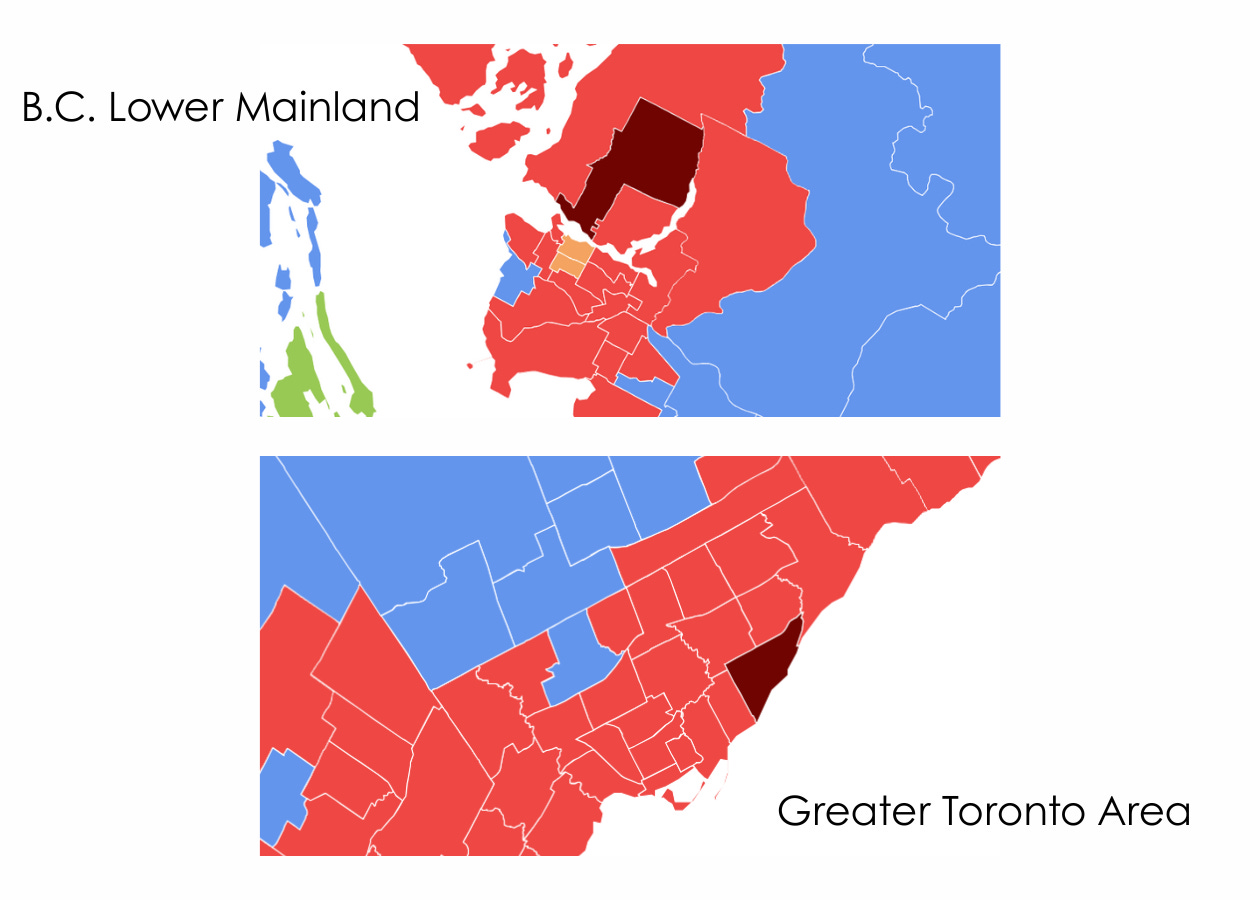

Blair has represented Scarborough Southwest since 2015. He won it by a margin of 31 points over the Conservatives with 61.5% of the vote in 2025. With the exception of the 2011 election, when the New Democrats took the seat, the Liberals have held what is now Scarborough Southwest since 1988. It would be a very tough seat for the Conservatives to win, considering that their 31% result in April was about as good as the party has managed to do in this part of Toronto over the last 35 years.

Wilkinson’s riding of North Vancouver–Capilano is perhaps a little more interesting. Wilkinson won handily by a margin of 26 points over the Conservatives with 59.8% of the vote. But the riding does not have as much of a Liberal history as does Scarborough Southwest. The Conservatives won all of the ridings north of the Burrard Inlet in both the 2008 and 2011 elections and part of the federal riding of North Vancouver–Capilano elected a B.C. Conservative in last fall’s provincial election. While Scarborough Southwest is one of the ridings the Liberals would be expected to hold regardless of the broader electoral climate, North Vancouver–Capilano is the type of riding that the Liberals win when they form a government and lose when they don’t.

It isn’t a question — at least not at this point — of whether the Liberals win these byelections. They almost certainly will, if they indeed occur. But they will provide a test of how Carney’s Liberals (and Poilievre’s Conservatives) are doing in some key constituencies. If Blair and Wilkinson do pack their bags for Europe, I imagine Carney will not want to risk waiting very long before putting his party back in front of voters.

ELECTION NEWS BRIEFS

NDP LEADERSHIP - Last week, the Toronto Star reported that Alberta MP Heather McPherson and Avi Lewis, son of former Ontario NDP leader Stephen Lewis and grandson of former federal leader David Lewis, are preparing bids for the leadership of the New Democratic Party. No candidates have yet been officially approved by the NDP. These two would seem to set the race on course for a contest between a more moderate vision for the NDP (McPherson) and a more populist, left-wing approach (Lewis).

ALBERTA PC PARTY - The membership of the Alberta Party has voted to change its name as the party intends to adopt the Progressive Conservative label. It’s not clear yet whether this request will be granted by Elections Alberta. The Alberta Party ran a full slate and received 9% of the vote as recently as the 2019 election, but collapsed down to just a one-fifth slate and 0.7% of the vote in 2023. Two MLAs who were booted from the UCP caucus, Peter Guthrie and Scott Sinclair, have been involved in the name change and could sit as PC MLAs should it be approved.

POLLING HIGHLIGHTS

Few other signs of Liberal slippage just yet

I discussed last week what to make of the Abacus Data poll that put the Conservatives (marginally) ahead of the Liberals for the first time since the election, and how we would have to wait for more polls to know whether or not Abacus is picking up a new trend that is turning against the Carney Liberals.

So far, the evidence is not supporting a significant downturn in Liberal fortunes.

The latest iteration of the four-week rolling Nanos Research poll shows the Liberals have hardly budged with the addition of a new week of polling. The Liberals stand at 43.3%, down 0.4 points from where they were the week before. The Conservatives, meanwhile, dropped 1.8 points as the margin between the Liberals and Conservatives widened a tad.

On the preferred prime minister question, Carney has slipped 0.9 points from 52.2% to 51.3%, while Poilievre went up 0.5 points to 27%.

This isn’t much movement and we shouldn’t make too much of the small fluctuations in the Nanos poll considering how it samples 250 new respondents per week. But these numbers do not suggest any big shift going against the Liberals.

Liaison Strategies (in a poll centred on back-to-school) also showed no movement. It has the Liberals at 44% and the Conservatives at 35% in its survey fielded August 25-27, unchanged from where things were in its previous poll at the beginning of August. Carney’s approval rating has gone from 64% to 63%.

Really, we’re not seeing much change. But we’re still only talking about a few data points. Nevertheless, I think it would be premature to conclude that the Liberals have taken a hit over the summer or that the Conservatives have gotten any sort of boost. It just looks like the status quo.

POLLING NEWS BRIEFS

ONTARIO POLL - After last week’s poll from Abacus Data that showed the Ontario PCs hitting a record high, a new poll from Liaison Strategies does not suggest that Doug Ford’s support is as impressive. The poll gives the PCs 44% support, followed by the Ontario Liberals at 35% and the NDP at 15%. While this is still a robust lead, and more support than the Ford PCs had in the February provincial election, it is far from a record-high — and, according to Liaison’s tracking, is actually down a couple points from where the PCs were at the end of the spring.

CALGARY & EDMONTON - The biggest electoral contests this fall will be at the municipal level, especially in Montreal, Calgary and Edmonton. Léger has some new data on the mayoral races in Alberta’s two big cities, finding many voters are undecided ahead of the October vote. In Calgary, only 33% think the city is going in the right direction. Incumbent mayor Jyoti Gondek has 15% support, followed closely by Jeromy Farkas, her main rival in 2021, at 14%. But 45% said they were undecided. In Edmonton, satisfaction with the direction of the city was no better than in Calgary. Amarjeet Sohi is not running again, leaving a wide open race led by Andrew Knack (12%) and Tim Cartmell (10%). Undecideds stand at 48% in the provincial capital.

FEDERAL PRIORITIES - Abacus Data put out some interesting numbers on how Canadians view the priorities and progress of the Carney government. Those top priorities include lowering costs, making housing more affordable and getting national projects and internal trade moving. Canadians are sensing progress being made on strengthening the military and the border and on internal trade and national projects, but think the government is dragging its feet on housing affordability and the cost of living.

12-MONTH ELECTORAL CALENDAR

September 24: B.C. Green leadership

Candidates: Adam Bremner-Akins, Jonathan Kerr, Emily Lowan

October 2: Municipal elections in Newfoundland and Labrador

October 4: P.E.I. Liberal leadership

Candidates: Todd Cormier, Robert Mitchell

October 14: Newfoundland and Labrador provincial election

October 20: Municipal elections in Alberta

October 27: Nunavut territorial election

November 2: Municipal elections in Quebec

November 3: Yukon territorial election

November 9: Québec Solidaire co-leadership

Candidates: Yv Bonnier-Viger, Étienne Grandmont, Geru Schneider, Sol Zanetti

March 29: Federal NDP leadership

May 11: Municipal elections in New Brunswick

Byelections yet to be scheduled

NB - Miramichi West (to call by September)

Party leadership dates yet to be set

Manitoba Liberals (Dougald Lamont resigned on Oct. 3, 2023)

P.E.I. PCs (Dennis King resigned on February 20, 2025)

Federal Greens (Elizabeth May announced on August 19, 2025)

Future party leadership dates

October 17, 2026: New Brunswick Progressive Conservatives

November 21, 2026: Nova Scotia Liberals

ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

The Mulroney Landslide

September 4, 1984

This was originally published on September 4, 2024.

When John Turner finally fulfilled his lifelong dream to lead the Liberal Party and be Canada’s prime minister, he had an important decision to make.

When should he call the next election?

Turner was sworn-in as prime minister in June 1984, more than four years after Pierre Trudeau’s unlikely comeback win in the 1980 federal election. Time was running out for Turner to send Canadians to the polls, but he had some options. His more cautious advisors recommended he wait until the fall, or maybe even the next spring. After all, he wouldn’t want to interrupt visits to Canada by the Queen and the Pope. He could play the role of statesman for a few months, get Canadians used to the idea of a PM Turner and then call an election when the time was right.

His less cautious advisors, however, thought the time wasn’t going to get any better. The Liberal leadership race had given the party some momentum in the polls — Gallup had the Liberals ahead of the PCs by 11 points that June, a huge reversal from their 22-point deficit in March. Forecasts that the economy was going to take a severe downturn in the fall also worried Turner.

So, hoping to follow in the footsteps of Trudeau’s big victory in 1968 shortly after he had become leader, Turner decided to take the plunge. He visited the Queen in the U.K. and informed her that she would have to postpone her visit. He dissolved parliament and, nine days after becoming prime minister, sent the country to the polls.

It proved to be a serious mistake.

Party organization wasn’t a priority under Pierre Trudeau. It was something he left to his top advisors, and over the years the Liberals’ once formidable electoral machine had gotten rusty. Turner, too, had lost some of his political acumen during his time outside of politics. He replaced Trudeau’s seasoned veterans with his own out-of-practice team. Coming off a disorganized leadership campaign, Turner then embarked on a disorganized election campaign.

By comparison, the Progressive Conservatives under new leader Brian Mulroney were in terrific shape. The PC war chest was as full as that of the Liberals and New Democrats combined. Though their polling lead had disappeared during the Liberal leadership campaign, the party had led in the polls throughout 1982 and 1983 as Trudeau’s popularity plummeted. Whereas the Liberals were still getting their campaign team together and had just 40 candidates nominated, the PCs had more than 200 in place and were guided by Norm Atkins of Ontario’s Big Blue Machine.

The New Democrats had as many candidates nominated as the PCs, but they had lagged in the polls behind the other two parties, dropping to 11% in May and June. A party memo by Gerry Caplan put things in perspective:

A. Disadvantages

We are very low in all the national polls.

Everyone knows this.

Much of the media has lost interest in us and is writing us off.

Some say we are irrelevant to the present moment and there is no purpose in people voting for us.

The party was divided on strategy — pitch for government or for survival, take a left-wing or centrist approach on policy — but its leader, Ed Broadbent, was the only one with campaign experience and was respected by voters.

Though the Liberals were the ones who called the election, they appeared to be the least prepared. Turner was exhausted from the leadership contest and barely campaigned over the first few weeks. The party had no platform to present, no political pamphlets or brochures to share. While the PCs and NDP ferried journalists across the country on chartered jets, Turner flew commercial and left the media to fend for themselves to keep up.

Things started badly for the Liberals. Before Trudeau resigned the prime minister’s office, he had left a list of patronage appointments for Turner to make. They were the usual fare — cushy landing spots in diplomatic posts and the Senate for loyal Liberals — and Turner was reluctant to go ahead with them. But he gave his word (in writing) that he would go ahead with the patronage appointments and followed through on that promise, adding a few of his own to the list. The story dominated the first week of the campaign, and ensured that the breath of fresh air that Turner was hoping to give his new Liberal government stunk just as bad as the last one.

The second week was dominated by another faux-pas. Television cameras captured Turner patting the behinds of women, not once, but twice. Again, it made Turner look old-fashioned rather than as an agent of change, and it didn’t help when he defended himself as a “tactile politician. I’m slapping people all over the place. That’s my style.”

Attention then turned to two debates, the first being held in French. This was an important opportunity for Mulroney and the PCs, who hoped to make serious inroads in Quebec.

Mulroney, who grew up in the small town of Baie-Comeau on Quebec’s Côte-Nord, opted to run in the riding of Manicouagan, taking on a Liberal MP who had previously won with huge majorities. The PCs had long struggled in Quebec, but Mulroney had spoken of his desire to get Quebec to sign the constitution and, if necessary, to work with the Parti Québécois government then in power to get it done.

This openness ensured that the PCs got some help from the PQ’s well-oiled organization in Quebec. They were also helped by René Lévesque’s belittling of attempts to create a federal sovereignist party.

The federal Liberals, meanwhile, had gotten so used to dominating the province (they won 74 of 75 seats in Quebec in 1980), that their own electoral readiness was lacking. Liberals were divided between those who supported Turner and those who backed Jean Chrétien in the leadership race. Robert Bourassa, leader of the provincial Liberals and someone who had a testy relationship with Trudeau when he was premier, officially stayed neutral. But, unofficially, the PLQ was also helping the PCs.

Mulroney performed well in the French language debate. He presented himself as a Quebecer and spoke French more naturally and comfortably than Turner, whose fluent French was nevertheless more stilted. (Broadbent lagged well behind the other two). Though there was no ‘knockout punch’ during the debate, it propelled the PCs forward in Quebec as voters in the province saw in Mulroney a ‘favourite son’.

The knockout punch would instead wait for the English language debate.

It came down to the issue of patronage. Turner went into the debate getting contradictory advice — stay out of the fray and look prime ministerial, or go on the attack against Mulroney. As the debate neared its end, Turner took the latter tack, with disastrous consequences.

Patronage was an issue of weakness for Turner, but he nevertheless went after Mulroney on it over a joke the PC leader had made about how, in a similar position, he would have “been in there with my nose in the public trough like the rest of them”.

Mulroney didn’t shy away from the opportunity. He noted how he had apologized for that crack, but Turner did not apologize for his patronage appointments. Turner meekly responded that he had no option.

“You had an option, sir,” Mulroney defiantly responded, “You could have said: ‘I’m not going to do it.’ … You could have done better.”

A Southam News poll conducted before the debate gave the Liberals a two-point lead over the PCs. The next poll conducted in the week after the debate put the PCs ahead by nine points.

Turner’s honeymoon was over. The party’s strong support in pre-campaign polls had been superficial — once Canadians had seen that Turner did not represent change from the unpopular Trudeau government, they reverted to their previous opinions. The Liberals were collapsing. And their campaign hadn’t even started in earnest, as it was only after the debates that the Liberals finally secured a chartered plane and began touring the country. The media dubbed Turner’s plane ‘DerriAir’.

The polls got worse for the Liberals throughout August, as the PC lead grew to 15, 20 and sometimes 30 or more points. Turner had begun the campaign polling better on a personal level than Mulroney, who was seen as slick and inauthentic. By the end of the campaign, Mulroney was polling significantly higher than the incumbent prime minister.

Mulroney and the PCs kept the rest of the campaign on cruise control, hammering home the message of change and of “jobs, jobs, jobs”. The perception that the Liberal campaign was falling apart was not helped when Turner replaced his advisors with Trudeau-era figures.

A leaked internal memo from the NDP’s campaign admitted that the PCs were going to win a majority, “maybe even a huge majority”, and the party began to pitch for the need for some NDP representation to provide an opposition to the PC juggernaut. The New Democrats were bleeding support to the Tories in Western Canada, but they were also attracting disaffected Liberals. There was even hope among some of the more optimistic New Democrats that they could bound ahead of the Liberals into second place. The catastrophic Liberal campaign was opening up opportunities not only for the soaring PCs.

Mulroney and the PCs won a majority — and it was indeed a huge one.

The PCs secured 50% of the vote and 211 seats, the largest caucus ever elected in Canadian history (John Diefenbaker’s win in 1958 was a few seats short, but proportionately represented more of the seats then up for grabs).

The PCs made their most substantial gains in Quebec, where they won 58 seats, up from a single seat in 1980. They also gained 29 in Ontario, 12 in Atlantic Canada and nine in the West, sweeping every seat in Alberta and capturing a majority of the vote in Quebec and all four Atlantic provinces. The PCs took 47% of the vote in British Columbia and 48% in Ontario. It was a truly national victory, as the PCs found themselves with seats in both rural Canada and in every major city.

The Liberals were decimated. Support for the party fell 16 points to just 28%, up to then the worst result the Liberals had ever been dealt. Only 40 seats remained, 17 of them in Quebec, 14 in Ontario, where they suffered serious defeats in Toronto and the southwest, seven in Atlantic Canada and only two in the West — one in Winnipeg, the other Turner’s seat in Vancouver.

Shockingly, the New Democrats had survived the Tory onslaught. The NDP retained 30 seats, just two fewer than they had won in 1980. The party won 13 seats in Ontario, eight in British Columbia, five in Saskatchewan and four in Manitoba. They gained seats from the Liberals in Ontario where, in 1980, they had won only five. But they lost seats to the PCs in rural Manitoba and Saskatchewan, in the B.C. Interior and on Vancouver Island. It ensured that the NDP remained in third place across the country, even if they had more seats than the Liberals west of Quebec.

Would Brian Mulroney’s landslide kick-off a new PC dynasty? Would the Liberals’ catastrophe finally result in the inauguration of a left-right political system that pitted Tories vs. New Democrats?

The next few years would demonstrate that electing a huge caucus comes with its own problems. Brian Mulroney, John Turner and Ed Broadbent would all have one more election in them and the next decade would be among the most tumultuous in Canadian political history. But the re-alignment that seemed to be happening in 1984 didn’t hold. Another re-alignment would have to wait for a new set of leaders.

MILESTONE WATCH

On Wednesday, Pierre Poilievre marks three years as leader of the Conservative Party. He won 68% of the points on offer in the 2022 leadership contest, easily defeating Jean Charest, who finished second with 16%. It’s been a whirlwind three years for Poilievre, as he went from being the PM-in-waiting to losing both the 2025 election and his seat in Carleton, a riding he had represented for more than two decades. After winning last month’s byelection, Poilievre will return to the House as the MP for Battle River–Crowfoot.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Numbers will be dropping on Tuesday. The episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. If you want to get access to bonus and ad-free episodes, become a Patron here!

For the Edmonton and Calgary races do you have a sense of where the candidates (and retiring incumbent) sit on the political spectrum or which, if any, political parties they are members of?