Weekly Writ 8/7: Why Pierre Poilievre's fundraising edge is different

Conservatives have a massive fundraising advantage over the Liberals.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Wednesday morning.

Like clockwork, the Conservative Party posted another record-breaking fundraising quarter, dwarfing the intake of all of its rivals – combined.

With just under $10 million raised between April 1 and June 30, the Conservatives set a new all-time high for a second quarter. The other four parties that file quarterly raised a total of $5.9 million.

I’ll get into the details of the fundraising figures later on. But first, let’s take a peek at what the money fight between the Conservatives and Liberals has looked like ever since Justin Trudeau became Liberal leader in April 2013, and what makes it so much different now.

The chart below shows the average quarterly fundraising for the the two parties, broken down by who was Conservative leader at the time. (For Andrew Scheer, I excluded the period after he announced he would resign as leader but stayed on until his successor was chosen.)

There are a few takeaways from these numbers.

Firstly, the Conservatives have improved their fundraising game over the last decade. In the waning years of Stephen Harper’s tenure, the party raised about $5.7 million per quarter. That increased to $6.2 million under Andrew Scheer and $6.4 million under Erin O’Toole. Since Pierre Poilievre became leader, however, fundraising has sky-rocketed to an average of $9.35 million every three months.

Secondly, Liberal fundraising has been largely stable over this time. Before the Liberals were even in power, the party was able to raise about $4.3 million per quarter with Trudeau as leader. That increased to just over $4.4 million between 2015 and 2021, when their opponents were Scheer and O’Toole.

Fundraising has only dipped by about 9% since the end of 2022, when Poilievre came on the scene. The Liberals’ fundraising is down but it has not fallen off a cliff.

What’s changed is that the Conservatives are simply raising so much more money than they used to. For every dollar raised by the Conservatives under Harper, Scheer and O’Toole, the Liberals raised between 69 and 75 cents. Since Poilievre has supercharged the Conservatives’ fundraising, however, the Liberals are only raising 43 cents for every dollar donated to the Conservatives.

That’s a huge disadvantage. As I’ll explain below, that disadvantage has had some tangible consequences — such as the enormous disparity in advertising spending between the two parties.

Now, to what is in this week’s instalment of the Weekly Writ:

Breaking down the news on fundraising from the second quarter of 2024 at the federal level and in British Columbia, which is heading to the polls in October, as well as in Alberta.

Polls continue to show the Conservatives in the lead.

The U.S. election projection shows Kamala Harris now leading in national polls, but still trailing in the electoral college.

The Conservatives nearing a two-thirds majority if the election were held today.

A look at who is on the ballot in LaSalle–Émard–Verdun in this week’s riding profile.

The #EveryElectionProject goes back to the beginning: the 1867 Canadian election.

Yet another milestone for Justin Trudeau.

IN THE NEWS

Conservative fundraising dominance continues

The quarterly fundraising figures are in and, as usual, they are big ones — for one party.

Between April and June, the Conservatives raised $9,832,051 from 52,519 individual contributions. This represents the party’s best Q2 on record, with nearly $2 million more in donations than in Q2 2023. So far this year, the Conservatives have raised $20.5 million, their best-ever start to a year and more than the Liberals have ever raised over an entire year outside of an election.

The Liberals took in $3,774,567 in donations from 28,523 individual contributions and have so far raised $6.9 million in 2024. By the party’s own standards, that was a decent quarter — it is the Liberals’ best Q2 since 2019. But the $6 million gap between the Conservatives and the Liberals is one of the largest on record. The only worse quarters were the previous two.

The New Democrats raised $1,294,197 from 14,063 contributions, a rather middling quarter for the NDP. Their fundraising is down about $80,000 from this time last year, but up by about $110,000 from the year before that. The NDP has raised $2.6 million so far in 2024.

The Greens raised just $376,076 from 4,210 in the second quarter, the party’s worst Q2 since 2013. With $770,000 raised so far in 2024, the Greens are also on track for their worst fundraising year since then.

As mentioned last week, the Bloc raised $321,806 and the People’s Party took in $140,057.

The Conservatives’ advantage over the Liberals in fundraising remains staggering — and buys the party lots of stuff. According to the annual filings for 2023, the Conservatives spent $8.5 million in advertising last year, with $5.8 million of that going to television ads. The Liberals spent just $381,000 in advertising, with the NDP chipping in another $42,000. The Conservatives were outspending their two main rivals 20-to-1 on ads last year.

Despite this, the Conservatives ended 2023 with $16.2 million in the bank, compared to just $2.7 million for the Liberals. The NDP ended the year in debt. The party can continue to outspend the Liberals and NDP by a huge margin.

Granted, the Conservatives spend more on fundraising than the other two parties, spending about 24 cents for every dollar raised, compared to 19 cents for the Liberals. The NDP spends nearly nothing on fundraising. But even this extra expense for the Conservatives only puts a small dent in their fundraising edge. Taking into account fundraising expenses, the Conservatives netted out some $26.9 million in contributions last year, compared to $12.6 million for the Liberals.

B.C. NDP leads fundraising, but Conservatives closing gap

The governing B.C. New Democrats appear to be in good financial shape ahead of the province’s October election, according to second quarter filings published by Elections BC.

David Eby’s NDP led the way in fundraising between April and June, raising $2,268,000 — an especially impressive figure when you consider that the federal New Democrats raised only a little more than half that from a nationally-sized donor pool. It’s more than double what the B.C. NDP raised in the second quarter of 2023, suggesting the party is ramping up for the campaign.

That’s no surprise, but the performance of the B.C. Conservatives was notable. The party’s fundraising has long lagged behind its polling support, suggesting that support was a mile wide but an inch deep. But for, likely, the first time as a modern party, the Conservatives finished second in fundraising in the second quarter with a total of $1,108,000 in donations.

That’s huge for the party. To put it into context, in the second quarter of last year the Conservatives raised just $65,000. This is a 17-fold increase in just one calendar year.

Though the party has dropped to third (or fourth) in the polls, B.C. United still appears to have a robust organization behind it. The party managed to raise $620,000 in the second quarter, though that is down from the second quarter a year ago.

That’s the worrying sign in these numbers for BCU. Every other party increased its fundraising from both the first quarter of 2024 and the second quarter of 2023. BCU’s fundraising, like its polling support, is falling.

The Greens raised $336,000, up slightly from a year ago but still putting them far behind the other parties.

But the Greens, like the other parties, will have more money on hand than just what is donated to them. Parties receive a public subsidy based on their vote totals from the last campaign. This is what is keeping BCU competitive.

So far in 2024, BCU has received a grand total of just over $2.6 million in both donations and party allowances. The Conservatives, by comparison, received just under $1.6 million.

Thanks to its strong fundraising and the party allowance, the B.C. New Democrats are by far the wealthiest party in the province. Their two quarterly allowance payments, plus their first six months of fundraising, has put over $5 million in party coffers this year. The NDP can outspend its two rivals to its right, with some left over to use against the Greens, too.

It’ll be interesting to see how this money is spent during the campaign. The NDP can run a provincewide campaign, both because it has the money to do it and enough support throughout the province to make it worthwhile. The Conservatives also need to run a provincewide campaign if they intend to make a run for government, but might not have the resources to pull it off. The Greens can concentrate their resources in just a handful of ridings where they are competitive, mitigating their more meagre fundraising.

But what does BCU do? If it still has pretensions to be a major party, it might try to spread its resources across the province, perhaps spreading them too thinly. If, however, they instead follow the Greens’ playbook and focus on just a few ridings, the party might survive. Will pragmatism or denial win out?

ELECTION NEWS BRIEFS

The United Conservatives lead the way in fundraising in Alberta, with $3,506,000 raised so far in 2024. The New Democrats trailed behind at $2,264,000, but narrowly beat out the UCP in the second quarter. Fundraising numbers for the Alberta NDP leadership race, won by Naheed Nenshi at the end of the second quarter, will be published only in October.

THIS WEEK’S POLLS

No summer swing, this time

It’s been relatively light on the polling front over the last week, but we did get new surveys out of Léger and the usual update to the Nanos Research four-week rolling poll. The numbers are in line with what we’ve seen for the last few months.

It has made for a rather quiet summer. At the end of May and in early June 2023, both Léger and Nanos were showing a tight race. Léger had the Liberals ahead by two points nationally, while Nanos had the Conservatives ahead by three points.

By the end of August 2023, though, Léger had the Conservatives ahead by eight points. Nanos was lagging other polls and still had the Conservatives leading by just three, but the trend line was moving — down for the Liberals and up for the Conservatives.

We haven’t seen anything like that happening this summer. At the end of May, Léger had the Conservatives ahead by 19 points. The gap is at 18 now. Nanos had them ahead by 15 points. It’s 17 now.

It hasn’t been a full calendar year of double-digit Conservative leads just yet. The party moved ahead by at least 10 points at the end of September 2023 and hasn’t since looked back. But that 12-month mark is fast approaching, and a full year is a long time for opinions to be holding firm without also becoming locked-in.

The Weekly Writ’s U.S. Election Update

The polls continue to move toward Kamala Harris and the Democrats. She now leads Donald Trump in the polling average by one point, 48% to 47%. The two were tied in last week’s update.

The electoral college continues to favour Trump, but his advantage is shrinking. He leads in enough states to win 262 electoral college votes, compared to 226 for Harris. States worth 50 EVs are still up for grabs.

Since last week, the second congressional district in Nebraska has moved from a toss-up to a Democratic lean, while Harris is now narrowly ahead in one toss-up state: Pennsylvania. She trails in the other three.

The path for Trump is easier than for Harris. If he wins just one of Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, and takes all the states where he is more clearly ahead, he’ll return to the White House. Harris can’t afford to lose any of those toss-up states. Nevada, though also a toss-up, is not currently a factor in the electoral college calculations.

IF THE ELECTION WERE HELD TODAY

A steep drop for the Liberals in the seat projection this week, as they slip to only 56 seats. The other three parties take advantage, with the Conservatives getting the biggest bump of three seats, pushing them to 222. The Liberals drop seats throughout the country, with the Conservative gains coming in Western and Atlantic Canada, while the NDP picks up a couple in Ontario and the Prairies.

There have been no updates since last week to the provincial projections below.

The seat estimates are derived from a swing model that is based on trends in recent polls as well as minor tweaks and adjustments. Rather than the product of a purely statistical model, these estimates are my best guess of what an election held today would produce. Changes are compared to last week. Parties are ordered according to their finish in the previous election (with some exceptions for minor parties)

RIDING OF THE WEEK

LaSalle–Émard–Verdun (Federal - Quebec)

On September 16, voters in the Montreal riding of LaSalle–Émard–Verdun will be heading to the polls in a key byelection test for Justin Trudeau’s Liberals. (Another byelection will be held on the same day in the Winnipeg riding of Elmwood–Transcona.)

A few weeks ago, I profiled the riding in depth. You can check out that analysis here:

More candidates have been lined up for all the major parties since I wrote that piece.

The Liberals will be running city councillor Laura Palestini who, like her NDP opponent Craig Sauvé, represents a ward that does not overlap with the LaSalle–Émard–Verdun seat. She was appointed as the candidate by the Liberals, pre-empting a nomination contest in which a few candidates were hoping to put their names forward. It did not go over very well among those prospective candidates, who were signing up members in the riding, and suggests that local volunteers may be less than enthusiastic about the contest.

The NDP’s volunteers, on the other hand, have already received a visit from Jagmeet Singh, who helped put up signs last week.

The Bloc Québécois found their own Sauvé in Louis-Philippe Sauvé, who has worked as a staffer for the party. The Bloc appears to be banking on a campaign focusing on local issues, and the party’s Sauvé also received a visit from his party leader, Yves-François Blanchet.

The Conservatives have nominated small business owner Louis Ialenti, who previously ran for the party in the Saint-Léonard–Saint-Michel riding located at the other end of the city. Ialenti took just 10.5% of the vote in that seat in 2021. While that is better than the 7.5% the party managed in LaSalle–Émard–Verdun, he is apparently unafraid of putting his name forward where his party has no plausible hope of winning.

ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

Canada’s first election

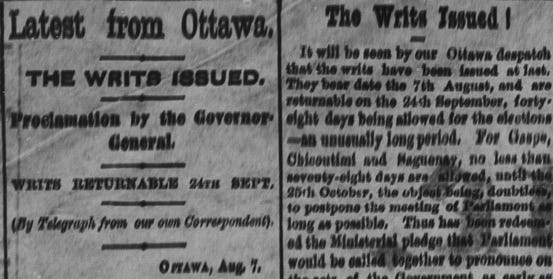

August 7 to September 20, 1867

When Confederation became reality on July 1, 1867, there were many things to get done. For starters, Canada had only four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Recalcitrant colonies such as Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland would have to be wooed. A railway would have to be built to link central and eastern Canada with the west before those settlements could be brought into the Union. The sparsely-populated and under-developed collection of British territories lying in the shadow of the American colossus to the south, itself self-confident and powerful after the end of the Civil War, would have to be turned into a country.

But first — an election.

As the main architect of Confederation, John A. Macdonald was invited to form Canada’s first government. Once sworn in, Macdonald shortly sent Canadians to the polls for the first time in a national election. But not all at the same time.

With no standardized election laws, campaigns were held in each of the four provinces according to their pre-Confederation electoral regulations. Who could vote varied from province to province, but it was largely limited to property-holding men. In Ontario, for example, it’s been estimated that only 16.5% of the population was eligible to vote.

How Canadians voted also varied. In Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, voting was done openly in public, often with a show of hands. Only New Brunswick had a secret ballot. Nova Scotia held elections in all ridings on the same day, while the other three held them on different days. The result was that voting took place at different times between August 7 and September 20, 1867.

Macdonald held many advantages. As leader of the Liberal-Conservative Party (as it was then called as a nod to the cross-party coalition of Liberals and Conservatives that worked together to bring about Confederation), Macdonald grouped together most of the pro-Confederation forces across the country. It was a more properly-organized party than the one on the other side of the aisle. The government’s powers of patronage, which Macdonald held and freely used, helped a great deal.

In Quebec, the Bleus were aligned with Macdonald while in Ontario he had the support of John Sandfield Macdonald, a Liberal member of his coalition. Rejected by other Liberals as little better than a traitor, the two Macdonalds hunted “in pairs”, splitting Ontario’s provincial and federal ridings between them to prevent John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives from having to face John Sandfield Macdonald’s “Coalition Reformers”. If both parties had interested candidates in a particular riding, they’d encourage one to run for provincial office and the other to stand for the federal campaign.

(Of course, running for both was an option. The first premiers of Quebec and Ontario were also sitting MPs.)

In Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, where elections could be held on different dates, Macdonald ensured that the more reliably Conservative seats voted first, in order to build some momentum that could be carried forward into less friendly parts of the country. Where voting was held over two days, the Conservatives could use bribery and threats to get out their vote on the second day when they found they were trailing after the first day of polling.

The Liberals weren’t above those tactics, but they were far more disorganized and had fewer resources at their disposal. They also had no official leader, George Brown being the de facto head of the Ontario Liberals, Antoine-Aimé Dorion the leader of the Rouges in Quebec. The Liberals (or Reformers, as they were often called) brought together those forces who had opposed Confederation, but were now largely reconciled to try to make it work.

Opposition to Confederation was strongest in Nova Scotia, where Joseph Howe led a slate of Anti-Confederate candidates. Mostly Liberals, the Antis didn’t want to try to make Confederation work. But they were hardly a united bunch. Some wanted to repeal Confederation entirely, while others wanted to amend it. Another group wanted Nova Scotia to deny that the Dominion existed, and refuse to send MPs to Ottawa.

The Antis were not incapable of overly-heated rhetoric. In one speech, Howe said that if “the British forces were withdrawn … and this issue were left to be tried out between the Canadians and ourselves, I would take every son I have and die on the frontier, before I would submit to this outrage.”

Violence was never far below the surface. If politics can seem nasty in the 21st century, it could be downright dangerous in the 19th. Alexander Mackenzie, a future prime minister and one of the top Liberals in Ontario, nearly fell into the hands of an angry mob while on the hustings. Mackenzie was prevented from speaking at a rally in Plympton and, when he tried to depart, the crowd blocked him from leaving and attempted to overturn his carriage and pull Mackenzie and the man he was travelling with into the crowd. When they finally got away, a high-speed horse-and-wagon chase followed, with Mackenzie’s pursuers “yelling and howling”, according to the Sarnia Observer, until Mackenzie’s carriage managed to escape.

No election was held at all in the Quebec riding of Kamouraska when a riot broke out on voting day, fought with “stones, cordwood and axe-handles”, according to author Norman Ward. “When I was dragged away,” recalled the returning officer, “through the yelling and vociferating mob, I am not conscious that I was struck, but in my agitated state I may have been struck without noticing it … and from my feelings next morning, at the back of my head, I am convinced that I had a few blows.”

There was little doubt that, with all of the incumbent government’s advantages, Macdonald’s Liberal-Conservatives would win. The party captured 100 seats (according to the Library of Parliament, though tallies differ from source to source), winning 49 in Ontario and 47 in Quebec, but just four in the Maritimes.

The Liberals won 62 seats, including 33 in Ontario — largely in the western portion of the province where they were strongest. George Brown, however, was not among the Ontario MPs elected and the long-time leader of the Reformers refused to stand in another constituency where voting had yet to take place when his defeat was announced at the end of August. The Rouges won 17 seats in Quebec and 12 of 15 in New Brunswick, where the Conservatives won the other three.

The Anti-Confederate vote in Nova Scotia was strong, with Howe being one of 17 Antis elected in the province. Only one Conservative, future prime minister Charles Tupper, withstood the Anti-Confederation wave.

(Alfred Jones, elected in Halifax, is listed as a Labour candidate by the Library of Parliament. Also, the record books for 1867 do not assign a party affiliation to dozens of defeated candidates, hence the large share of the vote awarded to “unknown” in the chart above.)

Macdonald was dismissive of the Anti-Confederate victory, calling it “a small cloud of opposition no bigger than a man’s hand.” He had a point. Within a few years, he would co-opt much of the party — including Howe, who joined Macdonald’s cabinet once the British government refused to reconsider Canadian Confederation.

It would take some time before Canada’s elections became a little more modern. The secret ballot and single-day elections would have to wait until Mackenzie’s Liberals came to power in 1874, largely in reaction to Macdonald’s under-handed campaign tactics. But Canada had its first election in the books.

MILESTONE WATCH

Trudeau now No. 7

He passed Robert Borden just days ago, and next week Justin Trudeau will pass Brian Mulroney as the seventh longest serving prime minister in Canadian history.

Mulroney served between 1984 and 1993, winning re-election once in the 1988 election. His landslide win in 1984, which delivered 211 seats to the Progressive Conservatives, remains the most seats ever won by a party (though John Diefenbaker’s 208 seats in 1958 represented a bigger share of the seats that were up for grabs).

The Mulroney years had some notable achievements, such as free trade with the United States, but also some notorious failures, such as the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords. When Mulroney stepped down as prime minister, his approval rating was in the mid-teens and his successor, Kim Campbell, famously won just two seats in the 1993 election.

The next prime minister on the list for Trudeau to run down is Stephen Harper, who he will only pass if he is still prime minister in August 2025.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Numbers will be dropping on Friday. The episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. If you want to get it early on Thursday, become a Patron here!