Weekly Writ 7/3: A short history of Battle River–Crowfoot

A look at the riding Pierre Poilievre is hoping will catapult him back into the House of Commons.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Thursday morning.

On Monday, Prime Minister Mark Carney set the date for the federal byelection in the Alberta riding of Battle River–Crowfoot, which Conservative MP Damien Kurek vacated in order to provide a seat for Pierre Poilievre.

There’s little doubt that Poilievre’s bid will be successful when voters go to the polls on August 18 — only one riding in the country gave more of its vote to the Conservative Party than did Battle River–Crowfoot. But if this is going to be the new seat of the leader of the official opposition, let’s take a tour through this sprawling riding and its political history, shall we?

Battle River–Crowfoot is a big riding occupying most of the eastern half of central Alberta. It runs from the Saskatchewan border to about 40 kilometres outside the northeastern limits of the city of Calgary and about 35 kilometres outside the southeastern limits of the city of Edmonton. It covers a lot of ground — all of it Conservative.

Battle River–Crowfoot is predominantly rural. Its largest community is Camrose, which has a population of about 19,000, a number that approaches 30,000 when including the surrounding county. Drumheller (about 8,000) and Wainwright (7,000), next-door to CFB Wainwright, are the next-largest communities.

The riding is also predominantly white, with just 6% being part of a visible minority (according to the 2021 census) and 5% claiming Indigenous identity. Poilievre’s old riding of Carleton, by comparison, was 17% visible minority. Fully 89% of the population has English as its mother tongue, with German being the second-most prevalent language in the riding. Indeed, 27% of the population claims German heritage.

The median household income in the riding is about $80,000, well below the province’s $96,000 and Carleton’s $135,000. About 6% work in the resource sector and another 15% in agriculture. Only 2% of Poilievre’s previous constituents worked in these two sectors.

So, it’s a very different riding for the Conservative leader. While Poilievre represented the most rural riding in Ottawa, the population was clustered in the federal capital’s suburbs, and many of them worked in the public service. Poilievre isn’t in Carleton anymore.

A Conservative stronghold

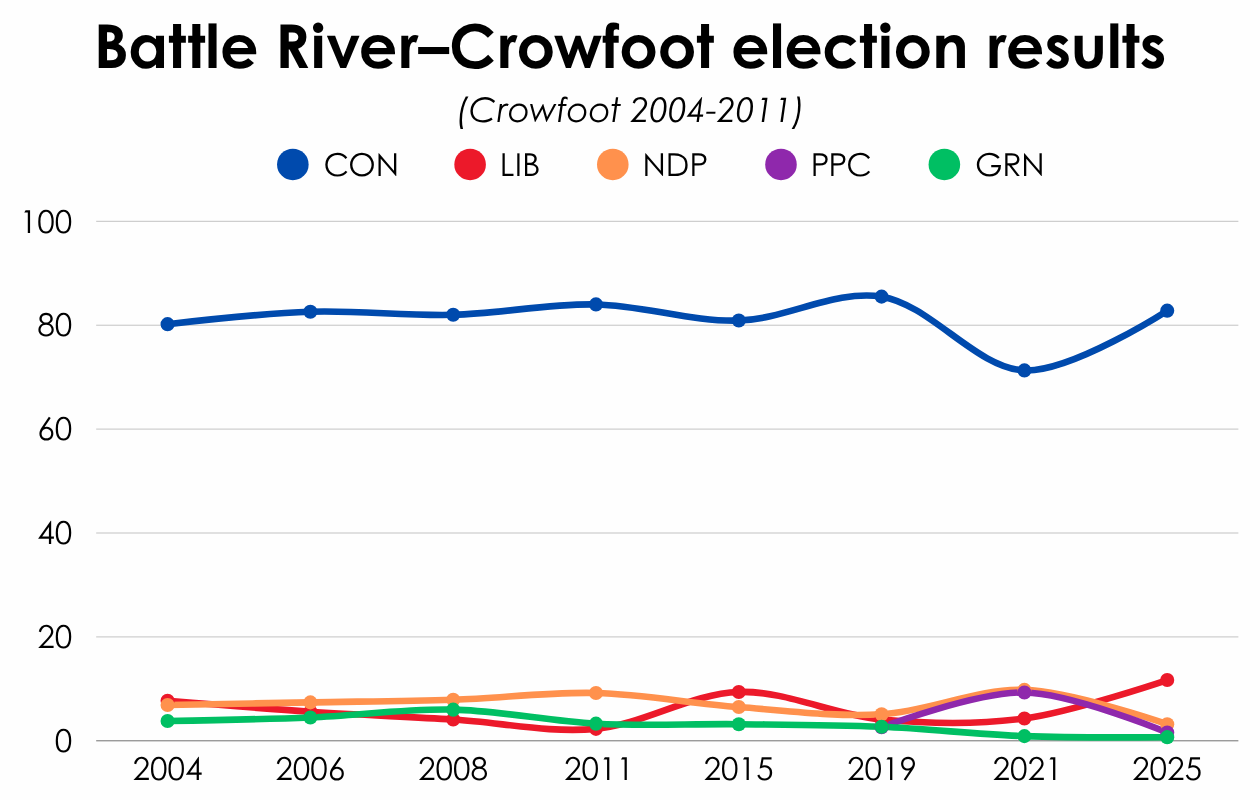

One of the biggest differences between Carleton and Battle River–Crowfoot might simply be in how it votes. The Conservatives’ share of the vote in Carleton over the last four elections has averaged 47%. The party has averaged 80% over that time in Battle River–Crowfoot.

In fact, the riding is one of the safest Conservative seats in all of Canada. It has ranked in the top three for the Conservatives’ highest vote share in every election since the merger between the Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservatives.

Kevin Sorenson, initially elected as an Alliance MP in 2000, won the seat (then known as Crowfoot, when it did not include the area around Wainwright but did stretch down to Chestermere) with 82% of the vote in 2004. He managed between 81% and 84% in every election he contested, his last being in 2015.

Damien Kurek took over the reins for the 2019 election and put up the Conservatives’ best result ever in this seat: just over 85%. That dipped to 71% in 2021, the only time the Conservatives have taken less than 80% of the vote in this riding as a unified party. This was primarily due to the rise of further-right parties — the PPC captured 9% of the vote in the riding in 2021, while the separatist Maverick Party took 4%.

The collapse of the People’s Party in the 2025 campaign helped Kurek get back over the 80% threshold. He took 83%, the second-highest vote share of any candidate in the country, with the Liberals finishing a distant second with 12%. That score nevertheless meant that the election was the first one in which two parties hit double-digit vote share since 2000.

The New Democrats, People’s Party and Greens managed crumbs at 3%, 2% and 1%, respectively.

Reform and Alliance years

With such strong Conservative numbers over the last two decades, it’s no surprise that prior to the merger this was Reform/Alliance territory.

A hint of what was to come first occurred in the 1988 election, the first contested by Preston Manning’s Reform Party. The PCs’ Arnold Malone, MP since 1974, won Crowfoot with 54% of the vote in 1988, but Jack Ramsay of the Reform Party finished a strong second with 32%. That was one of the best results for Reform in Alberta.

When the PCs fell apart in 1993, Ramsay was there again to win Crowfoot for Reform. A former leader of the Western Canada Concept party (he would subsequently run into trouble related to some criminal charges), Ramsay took 66% of the vote in Crowfoot in 1993 and formed part of Manning’s insurgent caucus that nearly formed the official opposition. The PCs took just 18% of the vote in that election in Crowfoot.

Ramsay would increase his score again in 1997 but would be booted from the Reform/Alliance caucus before the next election. His successor, Sorenson, took 71% of the vote in Crowfoot in 2000.

Between 1993 and 2000, the combined scores for the Reform/Alliance and PCs in Crowfoot ranged between 84% and 87%.

A shocking floor-crossing

In the decades before the rise of the Reform Party, this part of Alberta was safe territory for the Progressive Conservatives. In the 1960s, the riding was divided into two seats that were largely contiguous with the modern riding: Battle River–Camrose in the north and Acadia in the south.

In 1962, 1963 and 1965, Clifford Smallwood won the former and Jack Horner won the latter for the PCs. When the riding boundaries changed again, creating Battle River in the north and Crowfoot in the south, Horner held the Crowfoot seat with over 70% of the vote in 1968, 1972 and 1974. Cliff Downey, Harry Kuntz and Arnold Malone won in Battle River in each of those elections, though with scores not quite matching Horner’s.

When Robert Stanfield resigned the PC leadership after losing another contest against Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals, Jack Horner threw his hat into the ring to replace him. He finished fourth on the second ballot and endorsed Claude Wagner, who lost to Joe Clark.

Then in 1977 came the shocking news that the Trudeau Liberals had gained an Alberta MP via a floor-crossing. But it wasn’t an MP from Edmonton or Calgary, where the Liberals were usually more competitive. It was Jack Horner, who took a spot in Trudeau’s cabinet, saying he could get more done for his riding on the government benches.

The voters of Crowfoot disagreed. In the 1979 election, Malone ran against Horner in Crowfoot and won decisively — 77% to just 18% for Horner, now carrying the Liberal banner. Horner would try again in 1980 but would be no more successful, with Malone winning Crowfoot handily, and winning re-election again in 1984 as part of Brian Mulroney’s landslide.

The Diefenbaker re-alignment

That PC success in Alberta, as inevitable as it might seem today, was not always in the cards. It took a Prairie-based leader to make the PCs the choice of Albertans.

From 1935 until the 1958 election, this part of Alberta was represented by Social Credit — the governing party at the provincial level. Battle River was won by Socred Robert Fair in 1935 and he held the seat until a 1955 byelection, when Fair was succeeded by fellow Socred James Alexander Smith. Smith would win again in 1957.

The riding of Camrose was held by James Alexander Marshall from 1935 until the 1949 election, when Hilliard Beyerstein (another Socred) replaced him. Over in the Acadia riding (this area was split into three at the time), Victor Quelch took a majority of ballots cast in 1935, 1945 and 1949 (he fell just short in 1940, though he won). When Battle River–Camrose and Acadia were created before the 1953 election, Quelch succeeded Beyerstein and would win again in 1957.

But the arrival of John Diefenbaker, a Saskatchewan MP, at the helm of the Progressive Conservatives changed things for the party. His brand of blue-tinged Prairie populism resonated throughout Western Canada. In the 1958 election which remains the biggest landslide in Canadian electoral history, Smallwood defeated Smith easily in Battle River–Crowfoot (57% to 27%) and Horner beat Quelch in Acadia (50% to 29%). The Socreds would remain the PCs’ biggest rival in these ridings for another decade, but they would never again win a seat in what is today Battle River–Crowfoot.

From early days to Prairie populism

Prairie populism is an ongoing thread in this region, running through the Reform Party to Diefenbaker to Social Credit, as well as to the first instances of Prairie populism in Canada.

Like much of Western Canada in the early 20th century, this part of Alberta usually voted Liberal. The party won most or all of the territory currently occupied by the modern riding in 1896, 1900, 1904, 1908 and 1911. In 1917, the fight over conscription swung most of the region over to Robert Borden’s Conservatives.

But things changed in 1921. The First World War ruptured Canadians’ views on how things were supposed to be. New parties sprouted up, especially agrarian parties wanting to overthrow the old system maintained by the two old parties. In that election, this part of Alberta — like much of Western Canada — rejected Arthur Meighen’s Conservatives and elected a full slate of Progressive and United Farmer candidates.

Ahead of the 1925 election, the map was redrawn with Battle River, Camrose and Acadia occupying most of what is today Battle River–Crowfoot. Henry Alvins Spencer won Battle River and Robert Gardiner won Acadia as Progressives in that campaign, while William Thomas Lucas prevailed in Camrose as a United Farmer. The trio would be re-elected in 1926 and again in 1930, now all as United Farmers. Gardiner, a president of the United Farmers of Alberta, was even acclaimed in 1930.

But politics splintered again in the wake of the Great Depression. The Progressives and United Farmers were falling by the wayside. Gardiner and Spencer were part of the Ginger Group of MPs in the House of Commons that helped form the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), and all three MPs faced a new challenge from the emerging Social Credit movement, which espoused a kooky monetary policy that promised to solve the problems of the Depression (it wouldn’t).

In the 1935 election, both Spencer and Gardiner ran for re-election as CCF candidates. Lucas, however, joined the Conservatives. All three went down to defeat, as Fair, Marshall and Quelch won all three constituent parts of the modern Battle River–Crowfoot riding for the Socreds. The party would retain control of the region for more than two decades.

The electoral history of Battle River–Crowfoot is closely aligned with that of rural Alberta. Voters in this part of the province stick with the parties they like, and give them gargantuan shares of the vote — and, since the Great Depression, that has always been for right-wing candidates. This is not a riding that swings from one election to the next, unless there is a re-alignment on the conservative side of the spectrum. There is no danger of that here, so Poilievre has little to worry about. But the legacy of this riding is that its winners tend to win big. To keep up with that tradition, Poilievre will need to put up a big number — perhaps something that starts with an ‘8’.

Now, to what is in this week’s instalment of the Weekly Writ:

News on the death of one party and the potential rebirth of another, as well as a candidate coming forward to lead the B.C. Greens.

Polls show the Parti Québécois and the Liberals in a close race ahead of next year’s Quebec election. Plus, the federal Liberals enjoy a wide lead over the Conservatives, views on Manitoba separatism and where things stand in Ontario.

#EveryElectionProject: Allan Blakeney becomes leader of the Saskatchewan NDP.

The first Weekly Writ of the month is free to all subscribers. If you haven’t already subscribed and would like to get the Weekly Writ every Thursday (as well as access to everything else from The Writ), please upgrade your subscription today!

ELECTION NEWS BRIEFS

PARTY’S ON - Peter Guthrie and Scott Sinclair, two MLAs who were ejected from the United Conservative Party, are striving to revive the Progressive Conservatives to offer Albertans a centrist alternative. The PCs governed Alberta from 1971 until 2015 and agreed to a merger with the Wildrose Party to create the UCP. The PCs were officially dissolved in 2020.

PARTY’S OVER - The People’s Alliance of New Brunswick is officially going the way of the dodo. It nearly disappeared after party leader Kris Austin crossed the floor to the governing PCs (along with the only other People’s Alliance MLA) in 2022, but was kept afloat by some party activists who ran candidates in the 2024 election, garnering 0.9% of the vote. This week, the PA began the process to deregister permanently.

BC GREEN LEADERSHIP - The B.C. Greens finally have a candidate for their leadership. Comox councillor Jonathan Kerr is running for the post vacated by Sonia Furstenau shortly after the 2024 provincial election. The Greens have two MLAs in the legislature, neither of whom are running for the job. The party will select its new leader in September.

POLLING HIGHLIGHTS

PQ, Liberal fight returns in Quebec

Two new polls published in the last week add further evidence that Quebec might be reverting to its old Parti Québécois vs. Quebec Liberal fight, though with a far more divided electorate as five parties fight for seats in the National Assembly.

The polls come from Léger and Mainstreet Research. Mainstreet, which did not publicly release regional or demographic results, put the PQ narrowly ahead with 31% to the Liberals’ 29%. The governing Coalition Avenir Québec trailed with 16%, followed by the Quebec Conservatives at 14% and Québec Solidaire at 8%.

This is the first Mainstreet poll out of Quebec since before the last election, so we can’t look at trendlines. But we can for Léger, which shows the same sort of Pablo-Rodriguez-bump for the Liberals that was picked up by Pallas Data in the immediate aftermath of Rodriguez’s leadership victory.

Léger puts the Liberals at 28%, up eight points from its mid-May survey. Most other parties have dropped as a result of this shift, with both the PQ and CAQ down three points to 30% and 17%, respectively, and Québec Solidaire down one point to 9%. The Conservatives picked up a point to sit at 14%.

The Liberals hold a narrow six-point lead over the PQ in the Montreal region, but we can assume that much of that is on the island of Montreal and not in the surrounding suburbs. The PQ is ahead by 11 points in both the Quebec City region (over the Conservatives ) and the rest of the province (over the Liberals).

A simple regional swing model suggests this might not be enough for the PQ to win a majority, as it gives the PQ 58 seats to 36 for the Liberals, 17 for the CAQ, eight for the Conservatives and six for QS. Much of this, however, is due to the regional numbers in Montreal, as the PQ result isn’t high enough to swing enough seats over from the CAQ in the suburbs north and south of island. If the PQ’s support is disproportionately concentrated off the island, as we would expect to be the case, then it might easily find the five seats it would need for a majority. There are a lot of close races with these kinds of numbers — the PQ’s ceiling would be 75 seats, well over the 63-seat threshold for a majority government, while the CAQ’s floor would be seven.

The poll finds that half of Quebecers think François Legault should step aside as leader of the CAQ (and premier). But 28% think he should stay on, and those voters sticking with the CAQ think he should stick around, too. Only 10% of current CAQ voters think Legault should resign, compared to 88% who think he shouldn’t. Of course, the CAQ can’t win with its current crop of supporters. Léger didn’t ask if voters would be more likely to vote for the CAQ if he quit.

If he did quit, there wasn’t a clear favourite to replace him among the general population. Deputy premier and transport minister Geneviève Guilbault topped the list with just 12%, with health minister Christian Dubé, treasury board president Sonia LeBel and justice minister Simon Jolin-Barette trailing her by a few points. Among CAQ voters, however, Guilbault and Dubé were more obvious favourites.

Support for sovereignty came in at 33% in this poll, with 59% against. Some attention was paid to the high support for sovereignty among younger Quebecers, but it’s very possible this was just a statistical aberration as the overall support for sovereignty hardly budged from May.

POLLING NEWS BRIEFS

FEDERAL VOTE - Polls by Mainstreet Research and Nanos Research show the Liberals holding a robust lead over the Conservatives. Mainstreet puts the Liberals ahead by nine points, 47% to 38%, with the NDP trailing with just 6%, while Nanos has the gap at about 13 points, 44.5% to 31% and the NDP with 13%. Nanos continues to show a wide advantage for Mark Carney over Pierre Poilievre on preferred prime minister at 53% to 23%.

MANITOBA SEPARATISM - Tired: Alberta separatism. Wired: Manitoba separatism. Probe Research gauged views on independence in Manitoba and found that 22% of Manitobans would vote to leave Confederation if given the choice in a referendum, while 70% would vote to stay. Among the “definitely”, it was a 60-14 split. Interestingly, partisanship is the biggest predictor of separatist sentiment, as we’ve also seen in Alberta. Probe finds that a desire to remain in Canada is near unanimous among federal Liberals and both provincial and federal New Democrats, but that a slim majority of Conservative and PC voters would cast a ballot to quit the country.

ONTARIO POLL - Mainstreet Research finds the Ontario PCs leading with 41%, followed by the Ontario Liberals at 32% and the NDP at 17%. This is yet another poll that shows voting intentions in the province have hardly shifted since the February election. According to Mainstreet, Doug Ford has both a 44% favourable and unfavourable rating.

12-MONTH ELECTORAL CALENDAR

August 18: Federal byelection in Battle River–Crowfoot

September 24: B.C. Green leadership

Candidates: Jonathan Kerr

October 2: Municipal elections in Newfoundland and Labrador

October 4: P.E.I. Liberal leadership

Candidates: Robert Mitchell

October 14: Newfoundland and Labrador provincial election

October 20: Municipal elections in Alberta

October 27: Nunavut territorial election

November 2: Municipal elections in Quebec

November 3: Yukon territorial election

November 9: Québec Solidaire co-leadership

Candidates: Yv Bonnier-Viger, Étienne Grandmont, Geru Schneider, Sol Zanetti

Byelections yet to be scheduled

PEI - Charlottetown-Hillsborough Park and Brackley-Hunter River (to call by August)

QC - Arthabaska (to call by September)

MB - Spruce Woods (to call by September)

NB - Miramichi West (to call by September)

Party leadership dates yet to be set

Manitoba Liberals (Dougald Lamont resigned on Oct. 3, 2023)

P.E.I. PCs (Dennis King resigned on February 20, 2025)

Federal New Democrats (Jagmeet Singh resigned on April 28, 2025)

Future party leadership dates

October 17, 2026: New Brunswick Progressive Conservatives

November 21, 2026: Nova Scotia Liberals

(ALMOST) ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

Blakeney defeats Romanow

July 4, 1970

This was originally published on July 5, 2023.

Tommy Douglas is widely remembered as the father of Canada’s universal health care system after first introducing it in Saskatchewan. But it was actually his successor, Woodrow Lloyd, who turned the proposal into law, navigating it through the legislature and facing down the province’s striking doctors.

Lloyd got little thanks for his efforts. When he took his CCF government to the polls in 1964 (the Saskatchewan CCF had not yet followed the national party in adopting the New Democratic moniker), Lloyd went down to defeat against Ross Thatcher’s Liberals. Lloyd just wasn’t the firebrand and charismatic Prairie populist that Douglas was, and he followed up his defeat in 1964 with another in 1967.

Patience with Lloyd within the Saskatchewan NDP (as it was now finally known) had run out in 1970. In the federal convention the year before, Lloyd had voted in favour of a motion put forward by the Waffle that reflected the group’s socialist, radical views, greatly influenced by the anti-Vietnam War politics of American youth.

The motion didn’t pass, but the Waffle was starting to have a big influence within the national party — and the Saskatchewan wing, too. Members of the ‘Old Left’ and more pragmatic centrist wings of the party were not happy, and after a contentious caucus meeting in March 1970 Lloyd offered his resignation.

That put Allan Blakeney in an odd position.

Blakeney had long been a loyal supporter of Lloyd and had been deeply involved in the Medicare file as minister of health. Minutes were not kept, but Blakeney does not appear to have spoken out in defense of Lloyd at the caucus meeting, and the distaste he felt at how Lloyd was forced to resign led him to hesitate to run to replace his old colleague.

But Blakeney had always had his eye on the leadership and he was the first to announce. He had the experience to be leader. Though just 44, he had been a Regina MLA since 1960 and had been named to cabinet by Douglas before he had left provincial politics to take over the federal NDP.

After about a month, another candidate stepped forward: Roy Romanow. Just 30 (though he told the newspapers he was a few years older), Romanow had been first elected in Saskatoon in the 1967 election and was seen as a bright rising star within the Saskatchewan NDP. But he was also seen as representing the centre or centre-right of the party.

“[Romanow’s] campaign was modelled on the new era of television politics in the United States,” writes Dennis Gruending in his biography of Allan Blakeney, Promises to Keep. “He was photogenic, and had an easy way with people. There was a glitz and excitement to his campaign that Blakeney couldn’t match.”

With neither Blakeney nor Romanow being a spokesperson for the left, it was inevitable that other candidates from that side of the party would emerge. There was Don Mitchell, even younger than Romanow, who stepped forward as the unofficial candidate of the Waffle group, pitching public ownership of Saskatchewan’s farmland with a so-called “Land Bank”. There was also George Taylor, a venerable standard-bearer of the Old Left and the Regina Manifesto and a veteran of the international brigades of the Spanish Civil War. Taylor was there to avenge Lloyd’s defenestration.

While Blakeney put the emphasis on experience and Romanow on style, Mitchell focused on policy in the series of town hall debates that took place during the campaign. He might have pulled Blakeney and Romanow further to the left than they would have liked — the two eventually said his Land Bank idea wasn’t so bad after all — but the contest was always going to be between Blakeney and Romanow, between the establishment of the party and a new modern direction.

Some 1,600 people gathered at the Regina Armouries for the vote. The Waffle vs. Establishment battles continued in the contest for party president, and the win by the Establishment boded well for Blakeney. It was a shock, then, when Romanow narrowly emerged as the front runner on the first ballot with 35.3% of delegates’ votes to 33.6% for Blakeney. Mitchell took 22% and Taylor dropped off after taking 9.2% of the vote.

On the second round, Taylor’s votes split nearly evenly between the three other candidates, though Mitchell garnered more than either Blakeney or Romanow. The gap was closed between the leading candidates, and Mitchell dropped off after the second ballot.

Romanow had spoken out against the Waffle and Blakeney was also seen as opposed to the movement, so Mitchell decided to abstain on the final ballot. Taylor, though, tried to gather the old guard of the left behind Blakeney. While a big chunk of Mitchell’s supporters indeed abstained, Blakeney got more than three votes for every vote gained by Romanow on the final ballot, and emerged with a narrow win: 53.8% to 46.2%.

With a little guidance from Douglas, who suggested that his turn would come later (and it would), Romanow urged the convention to make the decision unanimous. Allan Blakeney would be the next leader of the Saskatchewan NDP — and return the party to power in 1971.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Numbers will be dropping on Tuesday. The episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. If you want to get access to bonus and ad-free episodes, become a Patron here!

Great stuff in here. But I do feel that this is no slam dunk for Pierre Poilievre. From various comment sections and comments I've seen on Facebook, many have stated they won't vote for him. We're about to find out just how popular he is within the party - I would think that anything less than a 70% win should spell some trouble for him.

If this happened in my riding, where my locally elected candidate won, only for him to resign right after so someone who lives far away can run and get a seat, the only reason that I would vote for him was if I actually liked him or not as the party leader.

Is the long-term shift in Alberta politics also due to changing party platforms (since the Liberals of a century ago are presumably very different from today’s Liberals)?