The Weekly Writ for Sept. 6: Poilievre's narrow path to a majority

Conservatives open up a big lead nationally; Doug Ford's PCs take a hit; and Manitoba goes to the polls.

Welcome to the Weekly Writ, a round-up of the latest federal and provincial polls, election news and political history that lands in your inbox every Wednesday morning.

I’ve long been of the belief that majority governments are tough to win in Canada these days — after all, it’s happened only twice in the last 20 years. But, as you’ll see below, the polls now have Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives in majority territory.

So maybe it isn’t so tough after all?

Think again. Despite what amounts to a roughly 10-point lead in the polls, the Conservative path to a majority government remains a narrow one.

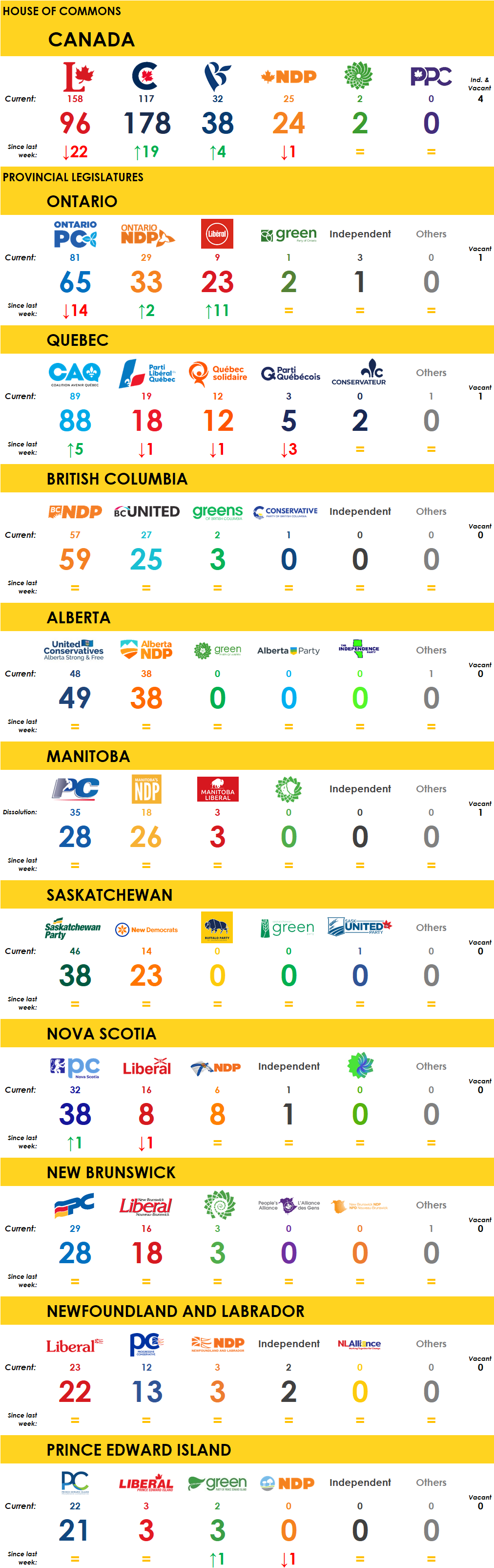

Today’s estimate puts the Conservatives at 178 seats, just above the 170-seat threshold needed for a majority government (which will increase to 172 on the new electoral map, but that won’t be used in any election until after April 2024). That eight-seat margin isn’t big, and it does depend on the Conservatives making some deep inroads in some tough places.

For example, those 178 seats include four of seven seats in Newfoundland and Labrador, which has been a difficult province for federal Conservatives for a long time. It also includes four of six seats in Mississauga, where the Liberals swept in 2021, and six within the city limits of Toronto, where the Liberals also swept last time. There are also three seats on Vancouver Island (24 in total in B.C., more than the Conservatives have ever won as a merged party) and a dozen in Quebec. Contrary to some of the popular wisdom, winning a majority without Quebec would indeed be tricky for the Conservatives.

These aren’t implausible victories for the Conservatives, but it does show that if any of these regions fall short — say Poilievre can’t break into Toronto’s inner suburbs and the NDP holds firm on Vancouver Island, or if the Conservatives drop in Quebec during the campaign and fail to woo Mississauga or Greater Vancouver — the party would suddenly find itself struggling to reach the bar of 170 seats.

That’s not to say they can’t, but the Conservative vote remains inefficient. The Liberals would win a massive majority with a 10-point lead. Not so the Conservatives.

Before getting to the Weekly Writ, here’s one more reminder to get your podcast feeds pointed towards The Numbers and Les chiffres, the two new podcasts that I’m launching with Philippe J. Fournier — tomorrow!

You can find all the links to the Apple, Google and Spotify podcast feeds here. You can also become a Patron at our Patreon site, which gets you access to our Discord as well as to exclusive episodes, which will start rolling out in a few weeks. You also won’t have to wait until Fridays — Patrons will get early access to all episodes on Thursdays!

Okay, let’s now get to what is in this week’s instalment of the Weekly Writ:

News on Manitoba’s election launch and an epic byelection showdown in Quebec.

Polls show the Conservatives moving into majority territory, while we have new numbers throughout Atlantic Canada as well as in Ontario and Quebec.

Conservatives would tip over 170, Liberals below 100 seats if the election were held today, while Ford’s PCs are getting into trouble.

Jean-Talon riding profile ahead of a big byelection.

The Original Orange Wave in the #EveryElectionProject.

François Legault passes another milestone.

IN THE NEWS

Manitoba election officially under way

Premier Heather Stefanson went to the lieutenant-governor’s yesterday to officially drop the writ on the 2023 Manitoba election campaign. As stipulated by the province’s fixed-election date laws, voting day will be on October 3.

After the drama of the Alberta election in the spring, Manitoba’s campaign hasn’t been getting nearly as much national attention. But it is a sleeper of an election that could prove to be really interesting.

The Manitoba Progressive Conservatives have been in power since 2016, though most of that was under the leadership of Brian Pallister. He stepped aside at the end of 2021 when his popularity was plumbing new depths, but his successor hasn’t done all that much better.

According to the Angus Reid Institute, Stefanson’s approval rating has never been higher than 26%. Their last two polls conducted in March and June put it at only 25% with two-thirds of Manitobans disapproving of her performance. Those will be very tough numbers to get out from under of.

But the PCs aren’t doing as badly in voting intentions as one might expect. The last poll from Winnipeg-based polling firm Probe Research had the PCs tied with the NDP at 41% apiece, quite a reversal from the NDP’s 11-point lead at the end of last year.

The New Democrats’ leader, Wab Kinew, has better personal ratings than Stefanson, but he still has greater unfavourables than favourables — so he does have his own issues when it comes to popularity.

However, the NDP does have one big advantage: Winnipeg. The provincial capital is where the majority of Manitoba’s seats are located and the NDP held a 16-point lead in the city in the last Probe poll. The New Democrats can win a few seats outside of Winnipeg (such as in Brandon and in the north), but their path to government runs through Winnipeg’s suburbs. Most of the rural seats will undoubtedly go to the PCs, so the NDP needs to win those suburbs to have a shot.

Complicating matters is the presence of the Manitoba Liberals under Dougald Lamont. While the Liberals only poll in the mid-teens and hold just three seats (with few prospects for a fourth), they could end up playing a huge role post-election. With the poll numbers where they are, it is not inconceivable that both the PCs and NDP could fall just short of the 29 seats needed for the slimmest of majorities — giving Lamont’s small caucus, assuming all three of its members can be re-elected, the balance of power.

There are broader implications at stake here as well. Stefanson and the PCs are happy to campaign against the federal carbon tax, so Manitoba is another test-case of the potency of that argument that Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives will want to watch. Kinew, if he wins, will become the first Indigenous provincial premier in Canadian history. As discussed with Dan Lett and Niigaan Sinclair on a recent episode of The Writ Podcast, that has implications on how this campaign could unfold.

And, while it has mostly been good news for the Blue Team in recent elections and in national polling, a defeat here for Stefanson could be the first setback for a provincial conservative party (of whatever stripe) since the B.C. Liberals fell short of a majority, and were subsequently ousted from power, in 2017.

Strap yourselves in — the next four weeks will be interesting! I’ll be keeping a close eye on the polls in Manitoba every Wednesday here in the Weekly Writ.

Quebec’s Jean-Talon byelection set

Acting as a bit of an hors d’oeuvre to Manitoba’s vote on October 3 will be a Quebec provincial byelection in the riding of Jean-Talon on October 2.

It’ll be quite a treat.

In the grand scheme of things, this byelection isn’t all that important. The province just held a general election a year ago and this one seat won’t change anything in the National Assembly. But the contest will nevertheless have some pretty high political stakes for two parties in particular: the Coalition Avenir Québec and the Parti Québécois.

I’ll get into the specifics of Jean-Talon in this week’s riding profile, but this byelection comes after the resignation of CAQ MNA Joëlle Boutin over the summer. Boutin says she wanted to spend more time with her family (though there was speculation she was disappointed she didn’t get a spot in cabinet). The resignation came at a delicate time for the CAQ, which has dropped in the polls in the Quebec City region following their reversal on the promised troisième lien, a tunnel under the St. Lawrence that would have provided another route between Lévis and Québec City for motorists. Instead, the tunnel (if it goes ahead) would be for public transport.

Since this decision, the CAQ has slipped into a near-tie with the Parti Québécois in and around Quebec City — and Jean-Talon is a Quebec City riding. The CAQ hasn’t lost much support anywhere else, but this byelection will put to the test the CAQ’s once-dominant position in the region. A loss here will corroborate the party’s poor polling, and probably make a lot of CAQ MNAs a little nervous.

For the PQ, this byelection is manna from heaven. The party has only three MNAs, two in eastern Quebec and one in Montreal, where leader Paul St-Pierre Plamondon has his seat. Winning in Jean-Talon would make the PQ the party with the momentum. Already second in the polls, its tiny holdings in the National Assembly make the PQ only the fourth party, well behind the official opposition Liberals and third-place Québec Solidaire. But a win would make the PQ, at least in the media narrative and perhaps in the public mind, the de facto opposition to the CAQ. A loss would put a halt to the PQ’s momentum — because, after all, polling in the low-20s is not that impressive, especially if you don’t do anything with it.

There are some side stories here, like the Liberals’ continued decline (as they cast about for a leader), the staying power of QS (which finished second in Jean-Talon in 2022) and the relevance of the Conservatives (who did not become the alternative to the CAQ in Quebec City, as one might have expected). But the big fight is between the CAQ and the PQ, and it’s clear that the CAQ knows this and is playing for keeps after leaking information about talks between the PQ’s candidate, Pascal Paradis, and the CAQ ahead of the last election.

This byelection will be one to keep an eye on.

THIS WEEK’S POLLS

Conservatives enter majority territory

Polling has been great for the Conservatives the last few months — and disastrous for the Liberals. Two polls in particular published over the last couple of weeks only hammered home the point.

These polls, by Abacus Data and Léger, gave the Conservatives a wide lead over the Liberals nationally, as well as in some key battlegrounds.

These sort of numbers — the Conservatives pushing 40%, the Liberals under 30% — have become so increasingly common that the trend is clearly set. A Mainstreet Research poll even had the Conservatives at 41% to just 28% for the Liberals. The lone dissenter at the moment is Nanos Research, which had a narrower 33% to 30% margin in favour of the Conservatives, but that four-week tracking poll fluctuates quite a bit.

Regionally, big Conservative leads in Ontario and British Columbia, with the Bloc edging out the Liberals in Quebec, have also become pretty standard, while Atlantic Canada is more or less a toss-up. That’s awful territory for the Liberals.

Will these numbers hold through the fall? And if they do — or, in the case of the Liberals, if they worsen — will the nerve of the Liberal caucus crack? I’m not one to believe that the Liberals need to replace Justin Trudeau, as it isn’t entirely clear that he’s the problem or that anyone else would do much better. In the Abacus poll, 29% of Canadians said they had a positive impression of Trudeau, while only 26% of decided voters said they’d vote for the Liberals (which would be around 23% of the entire electorate). That doesn’t suggest that Trudeau is necessarily dragging the Liberals down.

But it’s also not clear what advantages the Liberals still hold. With Pierre Poilievre, there was the potential that he’d be an abrasive and divisive leader who could turn people off from his party. But even that seems like an increasingly faint hope for Liberal strategists as there are signs that Poilievre has successfully burnished his image. David Coletto of Abacus Data tweeted on Monday that his polling shows more people with a positive impression of Poilievre than a negative one — a first.

The Liberals have time to turn things around and the Conservatives still have a lot of road ahead that they have to navigate carefully. But this could be an inflection point for the Liberal government. This round of polling is about as bad as it has ever been for them, with the possible exception of the SNC Lavalin affair. But that at least had a very specific cause — the current malaise doesn’t seem to be due to any one thing, which makes it all the harder to know what has to be fixed.

Greenbelt takes a bite out of Ford

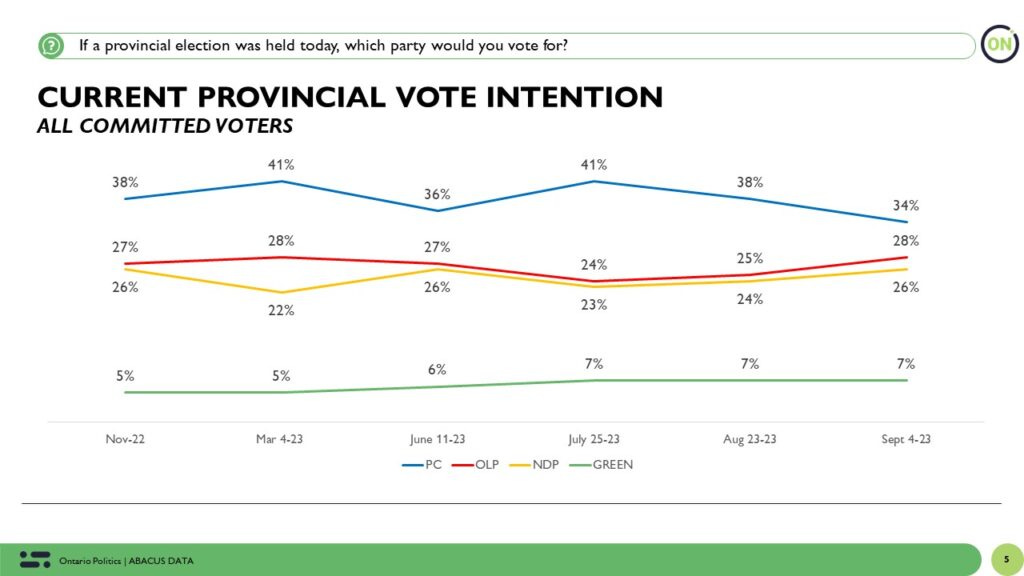

We had already seen in polls by Abacus Data and Pallas Data that Ontarians are both paying attention to and dismayed by the Greenbelt saga that has plagued Doug Ford’s PC government this summer, but we hadn’t yet seen any real impact on voting intentions.

So much for that.

Polling published by Abacus Data on Tuesday afternoon showed that support for the PCs had dropped to 34%, down seven points since the end of July. Both the Liberals and NDP have benefited, with the Liberals up four points to 28% and the NDP up two points to 26%.

That’s a rough trajectory for the Ontario PCs, and it is hard to divorce these results from the Greenbelt affair. (On the other hand, if you’re a PC optimist you could look at that June result and chalk this up to a meaningless wobble.)

Abacus finds the PCs now holding a good lead only in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area and in eastern Ontario (which, considering the Kanata–Carleton byelection, we can probably assume isn’t carrying over into Ottawa). It’s a three-way tie in Toronto, the Liberals lead in the north and the PCs are tied with the NDP in the southwest.

Within the GTA, Abacus finds the PCs doing best in York and Durham, but are behind in Halton and Milton and tied with the Liberals in Peel. In 2022, the PCs swept all of these regions.

This is just one poll, so we’ll have to see if any other surveys also catch this drop in PC support. With the next election still three years away, this might not matter too much. The PCs have recovered from bad polling before. But these numbers, combined with the resignation of housing minister Steve Clark, is a helpful reminder that (well, at least in this country) there can still be consequences in politics.

POLLING NEWS BRIEFS

While I was away last week, I missed the latest round of provincial polling from Narrative Research in Atlantic Canada. In Prince Edward Island, Dennis King’s PCs are still dominating. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the Liberals are in a tight race with the PCs but government satisfaction remains high. In New Brunswick, support for both the PCs and Liberals is up, while in Nova Scotia the poll corroborates the PCs’ recent win in a Halifax-area byelection.

Finally, in Quebec a poll by Léger finds the CAQ halting its decline, leading with 37% against 22% for the PQ, 15% for QS, 12% for the Liberals and 11% for the Conservatives. In the Quebec City region, the CAQ is only ahead of the PQ by two points.

IF THE ELECTION WERE HELD TODAY

Big shift from two weeks ago as the Conservatives jump to 178 and above the 170-seat threshold for a majority government, while the Liberals drop just below 100 seats. Nearly all of the changes have come in Ontario, where the polling from Abacus and Léger was very strong for the Conservatives. The Bloc also picks up a few extra seats in Quebec.

At the provincial level, Doug Ford’s PCs drop to the point where their majority is not so secure anymore, while strong results in the regions boosts the CAQ in Quebec at the expense of the PQ. Little changes in Atlantic Canada, though the Greens move into a tie with the Liberals for second place in PEI and the Nova Scotia PCs pick up yet another seat from the Liberals.

The following seat estimates are derived from a uniform swing model that is based on trends in recent polls as well as minor tweaks and adjustments. Rather than the product of a statistical model, these estimates are my best guess of what an election held today would produce, based both on the data and my own experience observing dozens of elections since 2008.

Changes are compared to last week. Parties are ordered according to their finish in the previous election (with some exceptions for minor parties).

RIDING OF THE WEEK

Jean-Talon (Quebec)

I’ve already described the stakes in the Jean-Talon byelection. Now let’s look at the numbers.

Support for the CAQ in this Quebec City riding wasn’t very high in the last election, as Joëlle Boutin won with only 32.5% of the vote. But the opposition was split and so her margin of victory was still relatively comfortable, as Olivier Bolduc of Québec Solidaire finished nearly nine points behind at 23.8%.

Behind him was the PQ’s Gabriel Coulombe (18.7%), Julie White of the Liberals (13.5%) and Sébastien Clavet of the Conservatives (10.4%). A handful of other candidates each took under 1% of the vote.

It had been a much easier victory for Boutin when she first won a 2019 byelection. In that contest, the CAQ captured 43% of the vote while the Liberals plummeted to just 25%.

It was a big defeat for the Quebec Liberals, as Jean-Talon had traditionally been one of their châteaux forts. Granted, the Liberals only won in 2018 in Jean-Talon by a margin of four points, but that gap had stretched to 22 points in the 2014 election. In every contest from 2003 to 2014, the Liberals won in Jean-Talon by at least double-digits. Before Boutin’s upset in 2019, this part of Quebec City had at least partially been represented by a Liberal since 1952.

One has to feel for the good people of Jean-Talon, as they’ve carried a particularly heavy democratic burden of late. In addition to the general elections of 2007, 2008, 2012, 2014, 2018 and 2022, there have been three byelections in Jean-Talon, in 2008, 2015 and 2019. This is the fourth byelection, and 10th election overall, held in this seat in the last 16 years. C’est trop.

This seat is located in the western suburbs of Quebec City along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River and just outside of the central part of the capital. It’s 92.5% francophone, and largely made up of the two former municipalities of Sainte-Foy and Sillery. In 2022, the CAQ did best in the Sillery polls (which had largely swung from the Liberals to the CAQ since 2018), while QS did better in those polls closer to the downtown Taschereau riding the party holds, as well as the polls in Sainte-Foy.

Despite finishing second here, though, Québec Solidaire might not be in contention this time.

In 2022, the CAQ won the Quebec City region with about 43% of the vote. Its nearest rival were the Conservatives, who finished with 21%. The CAQ beat the PQ by 30 points and QS by just a little less than that. But the most recent Léger poll puts the gap between the CAQ and PQ in the region at just two points, suggesting a net swing of 28 points between the two parties. That’s more than enough to cover the 14-point margin that existed in 2022 between Boutin and the third-place PQ candidate.

The swing would also technically be enough to put QS in range, but support for the party in the region hasn’t budged according to Léger. That would make it tough for QS to get north of the 30% mark it would probably need in order to win.

The CAQ is running Marie-Anik Shoiry as their candidate. She founded and runs a local charitable organization and is the daughter of a former mayor of Sillery.

Bolduc, who ran for QS last time, will be on the ballot again.

Pascal Paradis, a lawyer who co-founded Lawyers Without Borders Canada, will run for the Parti Québécois. His candidacy was greeted by word from the CAQ that they had been in touch with him about running for them ahead of the last election. The CAQ claimed that Paradis was demanding a cabinet seat, while Paradis has made it clear he was the one who was being approached, and that the party’s position on the troisième lien (pro at the time) was a red line for him.

Also on the ballot will be Élise Avard Bernier of the Liberals, Jesse Robitaille of the Conservatives and Martine Ouellet of Climat Québec. Yes, Ouellet is back again — the former PQ MNA and Bloc leader hasn’t had much success with the sovereigntist/environmentalist outfit she founded. The party took 0.3% of the vote in Jean-Talon in 2022.

ON THIS DAY in the #EveryElectionProject

Ontario’s Orange Wave

September 6, 1990

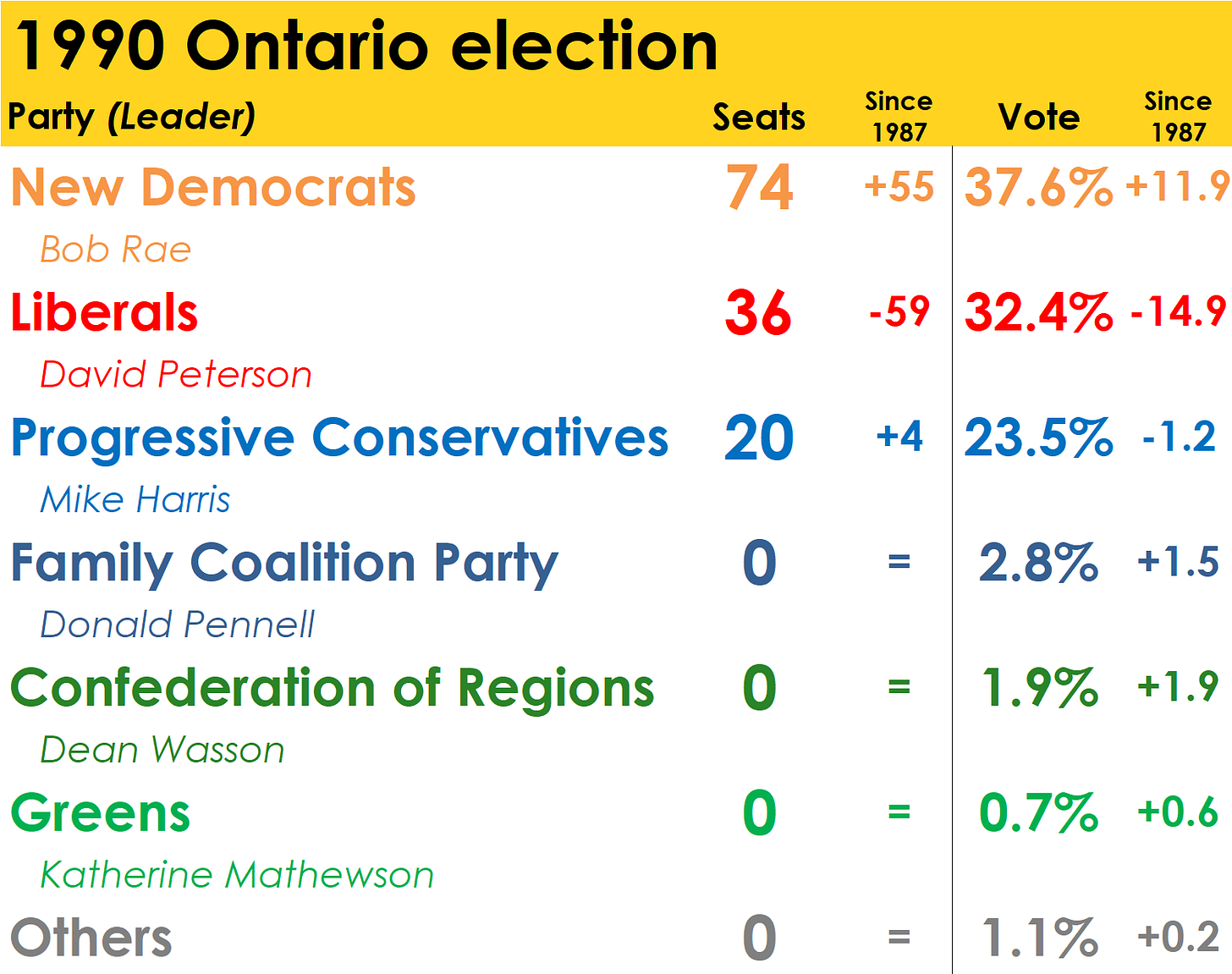

The 1980s were a time of political upheaval in Ontario. The long reign of the Ontario Progressive Conservatives that had begun in 1943 finally came to an end in 1985, when the Liberals under David Peterson and the New Democrats under Bob Rae combined to bring down the minority government that Frank Miller’s PCs had narrowly secured in that year’s election.

But after two years of co-operation between the Liberals and the NDP, Peterson eyed an opportunity — and won a huge majority government of his own in 1987.

Those string of successes suggested a keen political judgment on the part of Peterson, and so when the Liberals opened up a 20-point lead over the NDP in the summer of 1990, another snap election seemed like a good idea. Convention would have had the Ontario Liberals wait until 1991 or even 1992, but why pass up another sparkling opportunity?

Voters can spot a cynical political move from a mile away, though, and what seemed like a cakewalk for Peterson started off badly when the premier couldn’t quite explain the urgency for an early election call. “I don’t have to apologize for consultation with the people at this time,” he said — setting the tone for what Ontarians could expect for the next few weeks of campaigning.

Timing, of course, is everything. And the timing wasn’t particularly good for Peterson in the late summer of 1990, despite what the polls were saying.

Ontarians were grumpy. The economy was starting to tip over into recession. The Liberals were in the midst of a corruption scandal and were facing protests and organized opposition from environmental activists, teachers’ unions and doctors over government policy. Voters were upset with the province’s high taxes. They also weren’t too keen on Peterson’s involvement in negotiating the Meech Lake Accord with the unpopular prime minister, Brian Mulroney.

Disregarding these mounting problems, the Liberals tried to run a frontrunner’s campaign. Peterson even went so far as to avoid mentioning his opponents’ names in the early days, instead touting the economic performance of Ontario (even if Ontarians weren’t necessarily feeling the impact of those sunny statistics).

His opponents, however, weren’t going to give Peterson and the Liberals an easy go.

The Ontario Progressive Conservatives were still reeling from their third-place showing in 1987. But they were now under the leadership of Mike Harris, who took over the party in May 1990.

Harris was very much in the mould of the 1980s and 1990s small-government conservatives like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. He promised a tax freeze and to get the government out of the way of business, which he claimed was being stifled by Peterson’s high-tax regime.

The New Democrats took an alternative route. Rae, who was now in his third election as Ontario NDP leader, attacked the government for being too close to big business and property developers. He attacked the Liberals on their environmental record (a growing concern at the time) and promised to reform the tax system, institute a publicly-run auto insurance programme, increase the minimum wage and bring in measures to help workers.

It was all having an effect. Harris’s attacks on taxes focused the campaign narrative on a weak issue for the Liberals. The cynical snap election call sapped Peterson’s image and Rae’s disciplined campaign was moving the numbers.

In June, the NDP had scored only 26% support in an Environics poll. But a mid-campaign survey put the NDP at 34% and only six points behind the Liberals, who had slumped 10 points since the writ drop. The PCs weren’t moving, but they were holding their vote.

Polls were showing the New Democrats were now more trusted on issues like taxation and the environment — and on running an honest government.

The Liberals saw the shift in the numbers, and started going on the attack against the PCs and NDP. What was seen in some quarters as a desperate move in response to Harris, Peterson announced he’d cut the PST by a point.

Starting out as focused on another big Liberal majority, discussion turned to a potential minority government — and then an NDP victory. One poll at the end of the campaign showed the NDP ahead by about four points. The net swing between the Liberals and the NDP over the course of the campaign was around 30 points.

In the final stages, the desperation became more obvious when the Liberals went on the offensive against the NDP, raising the spectre of a socialist menace about to descend on Ontario. It didn’t work.

The NDP’s momentum crested on election day and the party captured 74 seats — a massive increase of 55 since the last election. The New Democrats won seats in every region, jumping 12 points since 1987 to 37.6%.

The Liberals were crushed. The party fell 15 points to just 32.4% and was reduced by 59 seats to 36. Those surviving MPPs did not include David Peterson, who lost by a wide margin to the NDP’s Marion Boyd in his riding of London Centre. Peterson resigned on election night.

Harris and the PCs took a little less of the vote than they did in 1987, but their seat count had increased by four to 20, a respectable showing for a party that some pundits thought would drop to single digits. Harris, who was only a few months into the job, would stay on.

The PCs could have done better had it not been for the vote taken by two parties to their right: the Family Coalition and the Confederation of Regions, parties motivated by social conservatism and anti-bilingualism, respectively. In 11 ridings, the combined vote of the Family Coalition and COR was greater than the margin between the losing PC candidates and the victorious New Democrats. The NDP had secured its majority by nine seats.

It was a big victory for the NDP, its first in any province east of Manitoba. It came at a time when the Mulroney PCs were deeply unpopular and the federal New Democrats were polling strongly. In 1991, the NDP would return to power in British Columbia and Saskatchewan. Things seemed to be changing in Canada, and Bob Rae had an opportunity to establish the New Democrats as a party of government in the country’s most important province. Hopes — and the stakes — were high. Would the 1990s finally be the NDP’s moment in the sun?

MILESTONE WATCH

Legault passes the OG nationalist premier

On Sunday, François Legault will pass Honoré Mercier as the 11th longest serving premier of Quebec.

Mercier served between 1887 and 1891 and came to power on a wave of French Canadian nationalism, transforming the Quebec Liberal Party into a “national” party that included both Liberals and Conservatives. This came shortly after the execution of Louis Riel by (Conservative) prime minister John A. Macdonald, a cause célèbre in Quebec as Riel, a francophone Métis and Catholic, was seen as a national hero and martyr of French Canada.

It proved to be a relatively short stint in office for Mercier as his government was toppled by a corruption scandal. While François Legault is only the latest heir of the Quebec nationalist mantle that Mercier pioneered, he must hope he will not meet the same fate.

That’s it for the Weekly Writ this week. The next episode of The Writ Podcast will be dropping on Friday. As always, the episode will land in your inbox but you can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting apps. And don’t forget to subscribe to my YouTube Channel, where I post videos, livestreams and interviews from the podcast!

Any idea where we can find old election platforms? Would be interested in the details on the big issues in the 1990 ON election.

Also anit-bilingualism in Ontario 1990 was an issue? Was this in response to bill 101? Or was something else at play?

The Ontario NDP's win in 1990 was my introduction to Ontario politics, partly because it seemed *everyone* was talking about it being such a big deal, but also because my Grade 11 Entrepreneurship teacher talked about the results in class. Specifically, despite him apparently being an NDP supporter (according to a fellow student), my teacher wrote "NDP" on the board and said voters were really voting "No David Peterson"! I thought his point was rather amusing, and it made me interested in following Ontario politics more closely.