Ontario's election done differently

Why Baden-Württemberg's electoral system is the answer to everything

The results of the Ontario provincial election have gotten electoral reform advocates hot under the collar.

The Progressive Conservatives won 67% of the seats and a majority government with less than 41% of the vote in an election with turnout of 43.5%.

While the New Democrats won a more reasonable 25% of the seats with 24% of the vote, the Liberals were rewarded with just 6% of the seats with the same 24% of the vote as the NDP. The Greens, with 6% of the vote, won a single seat, or less than 1% of those on offer.

That’s what our single-member-plurality electoral system, better known here as first-past-the-post (FPTP), can do. It’s all about winning the most votes in each individual riding, not about proportionality. So, the results can be pretty distorted, at least compared to how people voted across an entire region, province or country.

To reform or not to reform

I’m not an advocate for electoral reform, but nor am I a defender of the status quo. I’m somewhat agnostic when it comes to the question as I see the merits of both sides of the argument.

Proportionality is a worthy goal to ensure that every voice (or nearly every voice) gets representation and that every vote (or nearly every vote) counts. There is something unnatural about how representation in our legislatures does not reflect how the vote breakdowns.

On the other hand, I’m partial to the idea of voters electing people from their individual communities to represent them. The 124 MPPs at Queen’s Park (or 338 MPs in the House of Commons) are not the sum total of every ballot cast, but the sum total of 124 communities deciding who they prefer to speak for them.

I know there is naivety in that view — voters tend to vote for a party or leader rather than for their local candidate. But the concept has value.

That one system produces strong governments and the other produces cross-party collaboration is, to me, a little besides the point. An electoral system should be based on what our democratic principles are, not what the results would be. Perhaps that is naive as well, but if good governance was our goal we would have to re-think a lot when it comes to how our democracy works, since what it takes to win elections these days is not necessarily a good measure of a person or a party’s aptitude for governance.

The Conservative leadership race is a case in point. What does being good at selling membership cards have to do with leading a parliamentary caucus or running a government?

Still, if we were to reform our electoral system, what system should we adopt?

Clearly, there is only one answer.

Say it with me: BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG!

Baden-Württemberg’s wunderbar electoral system

If any of you have been following me since my Pollcast days, you know that my love for Baden-Württemberg’s electoral system is a bit of an inside joke (mostly because it is fun to say “Baden-Württemberg”). But I do think it is a system with a lot of attractive qualities.

In short, it is a mixed-member proportional representation system (MMP). People vote for local candidates, as with the FPTP system. But in addition to the 70 seats allocated to candidates who win their local districts (or ridings, as we’d call them), there are at least 50 top-up seats that are distributed to parties to achieve proportionality.

In the most recent election in this state in southwestern Germany, the Greens won 58 of the “first mandate” seats with just 33% of the vote, while the CDU won 12 seats with 24% of the vote and the SPD, FDP and AfD were shut out, despite each of these parties winning between 10% and 11%.

To achieve proportionality, the other parties were given top-up seats so that the CDU was awarded 30 “second mandate” seats, the SPD got 19, the FDP got 18 and the AfD got 17 seats. The Greens, since they had the most seats already, were not awarded any of the top-up seats. All 58 of their members were “first mandate” members.

Parties that achieved less than 5% of the vote were excluded. The results gave each of the parties a share of seats in the Landtag that was equivalent to the share of the vote that was awarded to eligible parties, and the Greens and CDU entered into a coalition.

As far as MMP goes, this is standard stuff. But in most cases, those top-up seats come from party lists. This means people vote for parties rather than candidates, and don’t (always) have much of a role in deciding who gets to populate the lists.

This is where Baden-Württemberg’s system is different — and why I like it so much.

The lists are populated by the candidates from each party who had the most votes in their ridings but failed to win a “first mandate”. This means that every candidate who is awarded a “second mandate” had significant support from voters in their constituencies.

For example, if a candidate from the CDU had 40% in her riding but finished a close second to the Greens, she would get a “second mandate” seat because her 40% ranked her among one of the top CDU candidates.

In addition to populating the list of top-up seats in a simple way that reflects voters’ preferences, this system means these members can also be held accountable. While a party might be penalized for doing so, with a party list an unpopular candidate could be placed high enough to ensure they get themselves a seat. With Baden-Württemberg’s system, unpopular candidates can be punished by voters and not only lose a “first mandate”, if they have one, but fall so far down the rankings for a party that they are deprived a “second mandate”, too.

I think it’s an elegant way to ensure voters have a say in who gets to represent them locally while still retaining proportional representation. Not only parties but individuals, too, can be held to account by voters — something that is not always possible with other MMP systems.

Ontario’s election, Baden-Württemberg style

That brings us back to the Ontario election. What would the results look like with Baden-Württemberg’s system?

Firstly, let’s get something clear: I am fully aware that if Ontario held an election with a different electoral system then the electoral results would be different. Parties would campaign differently and voters would vote differently.

But for the purposes of this exercise, let’s just apply the results of the election to this system to see what we get. If you like, you can imagine that a tyrannical Elections Ontario has decided it will retroactively apply a different system to the results of the June 2nd election. We’ll let the courts decide if they have that power.

A few notes: Baden-Württemberg divvies up the small state into administrative regions and awards the top-up seats according to how the vote broke down in each of those regions. For simplicity’s sake, I’m not going to do the same in Ontario. But a system like this in the province would likely divide Ontario into a number of sub-regions in order to allocate the “second mandates” and ensure those extra seats are awarded in a way that has some regional fairness.

In our exercise, there will be the 124 “first mandate” ridings that we currently have, and then whatever else is required to achieve proportionality. If we had the same ratio as Baden-Württemberg, it mean at least 89 “second mandate” seats.

Secondly, parties with less than 5% of the vote have to be excluded, so that means no New Blues or Ontario Party MPPs. It also means we have to re-calculate the vote shares. For example, the PCs received 40.8% of all votes cast but 42.8% of all votes cast for parties that cleared the 5% threshold.

Here’s how the results break down:

The PCs don’t receive any “second mandate” seats, but the Liberals get 41, the NDP gets 18 and the Greens get 11. Bobbi Ann Brady is still elected as an Independent in Haldimand–Norfolk.

In this scenario, Queen’s Park now has 194 MPPs, including 70 “second mandate” MPPs. The threshold for a majority would be 98 seats, meaning the PCs would need the support of either the Liberals or the New Democrats to govern, or the Liberals, NDP and Greens could govern together (a “traffic light” coalition, to borrow a German term).

Now for the fun part. Who would these “second mandate” MPPs be? We’ll start with the Liberals.

It’s a big list, but it includes all candidates who failed to win but scored at least 27.8% of the vote in their riding. It includes a few bigger names like Jeff Lehman, Amanda Simard, Nathan Stall and, of note, Steven Del Duca.

These Liberal “second mandate” MPPs are predominantly from Toronto and the Greater Toronto Area, with two from eastern Ontario and one from northern Ontario. The Liberals would get no top-up MPPs from southwestern Ontario, perhaps a reasonable outcome for the party considering how low Liberal support has been in the region.

Now for the New Democrats.

Here we see a few defeated MPPs saved with “second mandates”, including Faisal Hassan, Gurratan Singh and Gilles Bisson.

The NDP provides “second mandate” representation for southwestern and northern Ontario, as well as in Toronto and the GTA.

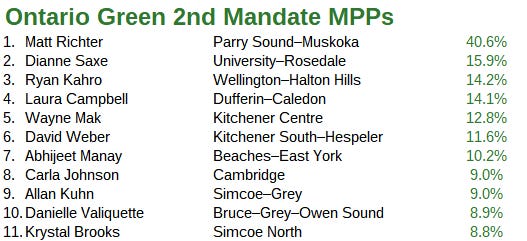

Finally, the Greens.

Matt Richter and Dianne Saxe get “second mandates”, along with a few other candidates primarily from Waterloo region and around Georgian Bay.

What’s interesting about this system is that voters across the province get both primary and secondary representation, with a pretty decent regional distribution. The PCs still have their “first mandate” MPPs spread out across Ontario, primarily in rural areas where the PCs have their highest support levels. Even without these seats being allocated geographically, you still don’t have much overlap — New Democrats in the north and southwest, Liberals in the GTA and Greens in and around Kitchener.

In the next election, everyone would start again striving for a “first mandate”, which means if the “second mandate” MPPs perform badly they can be punished at the ballot box and fall down their respective party’s list.

I like how this system doesn’t guarantee a leader a seat — in many MMP systems, the leader tops the party list. In this case, Doug Ford, Andrea Horwath and Mike Schreiner all get “first mandates” (and, being so popular, deny a “second mandate” seat to any of their local adversaries, which I think is a nice touch) but Steven Del Duca ranks only 20th on the Liberal list. You can easily imagine a scenario where an unpopular leader fails to finish high enough to get a seat.

Now to the reality.

Is a new electoral system in Ontario likely to be implemented? Absolutely not. The province already rejected a change in a referendum about 15 years ago and the PC government has no interest in or incentive to make any changes.

Nevertheless, the electoral reform movement might be given a little oxygen due to these results. We’ll see how things develop doing forward, but I still expect Canada and all its provinces (with perhaps a few exceptions) to continue using first-past-the-post for the foreseeable future, if not for the rest of my lifetime.

And that’s despite Baden-Württemberg being the glaringly obvious model to follow.

Auf wiedersehen!

The Weekly Writ will be back to its regular schedule next Wednesday. Until then, enjoy the Canada Day long weekend!

So all these newly elected and mandated 2nd chance would be answering to who Eric, the party?

I was not aware that Baden-Württemberg constructed its party lists that way. It's elegant, and goes in the direction of capturing some of the benefits of the single transferrable vote without the complexity and lack of transparency in allocating preferential votes and calculating quotas.

I agree that any electoral reform is unlikely to happen, especially as it has failed in every referendum where it was on the ballot. I have hoped that just one province would try a proportional system so we could see how it operated in the Canadian context.