#EveryElectionProject: The North

Capsules on Canada's territorial elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Canada’s three territories.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1992 Yukon election

Yukon Party wins Yukon

October 19, 1992

The New Democrats had been in power in Yukon for seven years by 1992 under Tony Penikett, the first Yukoner to adopt the title “premier” as a signal of the territory’s ambitions to one day become a province.

In the run-up to the territorial election that year, Penikett had spent a great deal of time outside Yukon on the national stage. This was the age of constitutional debates, and Penikett wasn’t too pleased with what was on the table in the Meech Lake negotiations that, in his view, would limit Yukon’s potential of achieving its ambitions.

Closer to home, though, politics was in flux. The PCs under Brian Mulroney had grown deeply unpopular, and the Yukon Progressive Conservatives decided it was time for a re-branding. The result was the new Yukon Party, which itself became divided when in 1991 it elected a 21-year-old named Chris Young as its new leader.

By the following year, Young was out and 56-year-old John Ostashek was in. The former outfitter didn’t hold a seat in the legislature and his party’s caucus had been reduced by three MLAs who quit to form the Independent Alliance Party.

These dynamics might have improved Penikett’s chances, but Yukon’s sluggish economy and the baggage of seven years in office weighed against the New Democrats. It didn’t help matters that Penikett was in the south so often.

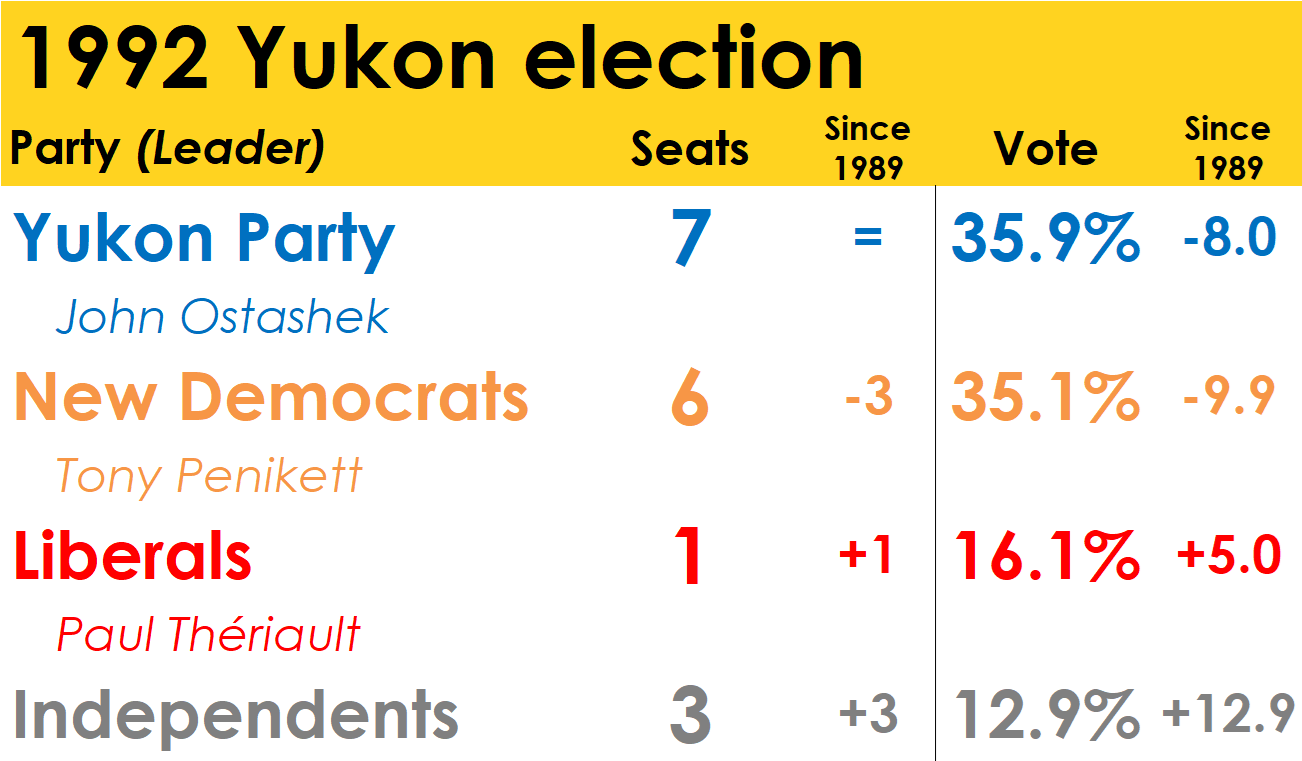

The result was a rebuke for Penikett and the NDP, as they dropped 9.9 percentage points to 35.1% of the vote and lost three seats, finishing with six. The Yukon Party also under-performed its PC predecessor with just 35.9% of the vote, down eight points, but Ostashek was able to win seven seats — just enough to put his party in first place.

"We've come a long way in one year," Ostashek said on election night. "It looks like Yukoners have told us tonight they want a change."

The Liberals got themselves back into the legislature after being shutout in 1989, but they were still outnumbered by the Independents. Though the Independence Alliance Party didn’t officially nominate candidates in time for the election, its three former-PC MLAs were all elected as unaffiliated Independents. While it was unclear at first who would form government, the three would back the Yukon Party and Ostashek would head-up a minority government for the next four years, re-adopting the traditional title of “government leader”.

Yukon wasn’t a province, after all. “I’m not for big titles anyway,” Ostashek said.

1999 Nunavut election

Nunavut’s first election

February 15, 1999

The long battle for the Inuit to have a land of their own, separate from the Northwest Territories, would finally come to a close in 1999 when Canada’s third territory, Nunavut, would be born.

Nunavut, a land twice the size of Ontario in which the Inuit represented about 85% of the population of some 25,000, would officially be created on April 1. But to get their legislators in place before that, an election would be held on February 15, 1999.

The 19 MLAs that would be elected would sit in Iqaluit, the small city on Baffin Island that had beaten out Rankin Inlet on the mainland in a 1995 plebiscite held to choose the new territory’s new capital. Those MLAs would continue the tradition of consensus government that prevailed in the Northwest Territories. There would be no political parties. All MLAs would sit as Independents and collectively choose the premier and cabinet ministers.

When the electoral rolls were completed, there were 12,200 people on it eligible to vote. Of them, 71 candidates put themselves forward to contest Nunavut’s 19 seats, including eight MLAs who were sitting in the Northwest Territories legislature.

The election was the culmination of a long journey, but the winners would take on a daunting job in creating a government from scratch in a territory with serious health challenges, high unemployment and few resources.

There were two favourites to win the premier’s job: Goo Arlooktoo, the young deputy premier of the Northwest Territories, and Jack Anawak, a two-term Liberal MP from 1988 to 1997 and the interim commissioner of the territory.

As the campaign got going — with no territorial parties, the contests were all localized — early turnout was high.

“People are finally starting to realize that with this election comes the start of a long-awaited dream,” Arlooktoo told the Canadian Press. When the votes were tabulated, turnout was over 88%.

Five of the eight veteran MLAs were re-elected, but the rest were all newcomers — a mix of young and old, but only one woman. The surprise, though, was the defeat of Arlooktoo in Baffin South. That seemed to leave the way open for Anawak, who was elected in Rankin Inlet North, to become premier.

But one shining newcomer to the scene was Paul Okalik, elected in Iqaluit West. Okalik was the first Inuk lawyer in the territory — he passed the Bar during the campaign. After a troubled youth, Okalik overcame addiction to earn a university education and was a member of the team that won the important Inuit land claim with the federal government that would lead to the creation of Nunavut.

The 19 MLA-elects met in Iqaluit in March to choose the premier and the territory’s first cabinet. While Anawak was widely seen as the favourite, it was Okalik who won the day as Anawak carried some of the political baggage of his time in Ottawa with the Chrétien government.

Only 34, Okalik would be the first premier of the newborn territory — a job his peers would award him again in 2004. He lost it after the 2008 territorial election, but his two terms still make him the longest serving premier of Nunavut.

1999 Northwest Territories election

When partisan politics tried to invade the North

December 6, 1999

When the Northwest Territories went to the polls in December 1999, there were a lot of big issues at stake.

The territory was facing a big debt burden. The resource sector was booming, but being a mere territory any industry-related revenues went south to Ottawa. And, with the creation of Nunavut only a few months earlier, this election was the first to be held since the territory’s size and population had been dramatically reduced.

Lots to mull over for the Northwest Territories’ 21,000 voters, spread out over 19 ridings.

But one of the issues that caught the most attention was an attempt to change the way politics in the territory worked.

N.W.T. used a consensus model of government, where MLAs were elected as Independent candidates. Once sent to the legislature, they would then choose a premier and cabinet minister from amongst themselves. Parties didn’t exist.

The Western Arctic New Democrats wanted to change that.

Though still listed as Independents, the NDP tried to put together a partisan slate running on a joint platform — a novelty in the territory. Six candidates ran as New Democrats, five of them in Yellowknife and one in Inuvik. To add a little southern glamour to their offering, NDP MP Svend Robinson swung by to campaign alongside the N.W.T. NDP.

None of the candidates, however, were incumbents. They were insurgents, trying to overthrow the old system.

Those who had come up through the ranks of that old system dismissed the attempt to bring partisan politics to the North.

"The people who are pushing party politics are people who have moved up here from the south,” Jim Antoine, the incumbent premier, told the National Post. “Up here, people vote for people they know who will do a good job representing them on the issues.”

But according to Steve Petersen, one of the candidates running under the NDP banner, "the problem is we don't have a consensus government, we have cronyism and an old boy's club. There's no opposition whatsoever.”

This had become a glaring problem in the last legislature. Don Morin, then premier, resigned over a conflict of interest scandal. If the legislature had an opposition to hold the government to account, this wouldn’t happen. This, at least, was the message of people like Mary Beth Levan, the highest-profile of the NDP’s candidates. She had run for the federal NDP in the last election in 1997, taking 19.4% of the vote and finishing second to the Liberal candidate.

But Northwesterners liked their consensus-style of government, considering it well-suited for a sparsely-populated, diverse and enormous territory.

"[Partisan politics] could take away the flexibility the people always have to find common ground," incumbent MLA Stephen Kakfwi told the Toronto Star.

In the end, the skeptics were right. All six of the NDP’s candidates were defeated, all but one of them finishing last. Levan managed 20.4% of the vote in Yellowknife South. But Petersen managed just 9.4% in Kam Lake. Bill Schram, another New Democrat on the ballot, also finished with under 10% of the vote.

Instead, voters stuck with what they knew. Eight of 10 incumbent candidates were re-elected, including Antoine and cabinet ministers like Charles Dent (finance), Floyd Roland (health) and Michael Miltenberger (education). Of the two incumbents defeated, one was the speaker of the legislature, Samuel Gargan.

The slate of elected candidates included two future premiers (Roland and Joe Handley) as well as Michael McLeod, who was elected as the Liberal MP in 2015.

As always in the Northwest Territories, though, the election results didn’t indicate who would form the next government. Over the holidays, Antoine mulled his future and decided not to stand again for premier. Instead, the job went to Stephen Kakfwi, a former president of the Dene Nation and the dean of the legislature who had held multiple cabinet portfolios in his previous 13 years in office.

Partisan politics weren’t established in the Northwest Territories in 1999. Nearly a quarter of a century later, partisan politics remain a southern concept.

2000 Yukon election

Don’t count your chickens

April 17, 2000

It’s rare that a truly surprising outcome happens in elections — and when it does happen, it often leaves some deep scars (largely on pollsters and adjacent pundits). But in smaller campaigns where pollsters don’t dare venture, sometimes the only thing to go on are the vibes. And those vibes can be wrong.

The Yukon territorial election in 2000 was expected to be a relatively easy one for the New Democrats. They had come to power after the 1996 election and had governed the territory for 11 of the previous 15 years. Government leader Piers McDonald was expected to get a second term in office.

Against him were the opposition Liberals. Their leader was a former sports broadcaster, Pat Duncan, but a relative newcomer to politics. McDonald had been an MLA for 18 years and John Ostashek, leader of the conservative Yukon Party, had been premier from 1992 to 1996. Duncan was first elected as an MLA in 1996 and was installed as leader of the Liberals only in 1998. But, the wind was in her sails following a byelection victory at the expense of the NDP in 1999.

In February 2000, McDonald introduced a half-billion dollar budget, with big (by Yukon standards) spending commitments and tax cuts. McDonald and the NDP would campaign on diversifying the territorial economy. That would be their issue.

But the issue for voters was that the economy was in the doldrums. Unemployment stood at 12%, the third-highest rate in the country, and the price of gold had dropped precipitously. Duncan and Ostashek blamed the NDP government for the collapse of the mining industry due to the creation of two parks in the north of the territory, and credited the departure of Yukoners to greener pastures in the South to the economic failures of the New Democrats.

Was the message resonating? It didn’t seem so. Expectations on election day were that the New Democrats would be re-elected, helped in part by a stronger-than-expected Yukon Party campaign that would split the anti-NDP vote. Headlines like the one running in the Ottawa Citizen on election day (which was also shared by Prince Edward Island) said “Incumbents likely to win P.E.I., Yukon votes today”.

“In the Yukon,” the paper reported, “observers don’t consider Government Leader Piers McDonald out of line when he predicts another majority government for his New Democrats.”

Oops.

The results were a huge victory for the Liberals, many of whom could not believe their eyes at the party’s election night party. They captured 10 seats and 42.9% of the vote, a huge increase of 19 points over the last election in 1996. The NDP won just five seats and shed seven percentage points, falling to 33%. The Yukon Party was reduced to a single seat.

Pat Duncan would become the first Liberal premier in the history of the territory, and only the second woman in all of Canada to lead her party to victory in an election campaign. But the results pointed at a split in Yukon, as all 10 of the Liberals’ seats were won in and around Whitehouse, while the NDP won the seats in the rural and remote communities in the rest of the territory.

Recognizing the divide, Duncan assured listeners of her victory speech that her “government will put all Yukoners ahead of politics no matter where they live.”

The election was a tremendous rebuke for the NDP. McDonald was defeated in his own riding, his first defeat since being elected to the legislature in 1982. Ostashek and the Yukon Party also took a big hit, as Ostashek, too, went down to defeat in his riding and resigned as leader of the party.

While it was a big upset victory for the Liberals, the euphoria would be short-lived. Within a few years, three of Duncan’s caucus members would leave to sit as Independents, reducing her majority to a minority. When she called an election in 2002 to settle matters, she and the Liberals were sent back to third-party status with a single seat (Duncan’s).

Of course, in Yukon, small swings can have a big impact. Between the 2000 and 2002 elections, the Yukon Liberals lost only 2,063 votes — but that was enough to lose them power, too.

2004 Nunavut election

Nunavut holds its second election

February 16, 2004

When Nunavut became a separate territory in 1999, Paul Okalik was voted its first premier by Nunavut’s legislative assembly. By 2004, it was time for Nunavut to hold its first election in which members were going back to voters for another mandate.

There are no political parties in Nunavut — candidates all run as independents. Once the members of the new assembly have their seats, those members then vote to choose who among them will become premier and who will make up the cabinet.

So, when Okalik sent the territory to the polls in 2004 he wasn’t necessarily going to voters to ask for his own re-election. That decision would not be up to him.

Turnout was high, as it had been in 1999, at over 80%. Okalik was re-elected in his riding of Iqaluit West, capturing 77% of the vote — more than any other candidate in Nunavut, a solid mandate from his own constituents. Not all incumbents were so lucky, however, as only eight of the 13 MLAs who ran for re-election were successful. Among the winning candidates were future federal cabinet ministers Leona Aglukkaq and Hunter Tootoo.

When the new assembly gathered, the race to become premier was between Okalik and Tagak Curley, who had been acclaimed in Rankin Inlet North. Okalik prevailed, but would only be narrowly re-elected in Iqaluit West in the next election in 2008. After more than nine years in office, MLAs decided not to install Okalik as premier again for a third term and turned instead to Eva Aariak — one of only 14 women to ever serve as a provincial or territorial premier in Canada.

2015 Northwest Territories election

Continuity with change in the Northwest

November 23, 2015

The Northwest Territories, like Nunavut, operate under the so-called “consensus” model. There are no parties in their legislative assemblies. Instead, voters send Independents to their legislatures and let them figure out who should be premier and who should be in cabinet.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t pass along a message of change.

Change was in the brisk air of the Northwest Territories in November 2015. The territorial election set for November 23 of that year came just about a month after the 2015 federal election (which forced the set date for the territorial vote to be pushed back).

With Stephen Harper’s Conservatives out and Justin Trudeau’s Liberals in, it had certainly been a change election across Canada. That was also the case in the Northwest Territories, as the NDP incumbent went down to defeat against the Liberal candidate, Michael McLeod.

There were plenty of good reasons for change in the territory — a CBC analysis listed 18 of the challenges that the incoming territorial government would face — and voters (or, at least, the 44% of Northwesterners who cast a ballot) delivered that change in what were some very tight local races.

Three of the 19 seats up for grabs were won by candidates who captured less than 30% of the vote: Kevin O’Reilly in Frame Lake (28.6%), Shane Thompson in Nahendeh (29.4%) and Daniel McNeely in Sahtu (29.6%).

Five races were decided by less than 20 ballots, including the contest in Range Lake where (current premier) Caroline Cochrane defeated incumbent Daryl Dolynny.

Dolynny was one of eight incumbents who went down to defeat out of the 16 who stood for re-election — a message for change if there ever was one. Even the finance minister was sent packing.

But the premier wasn’t. Bob McLeod, brother of the new Liberal MP, was re-elected in his own riding and the new legislature would keep him on as the premier, the job he first got after the 2011 election.

That, in and of itself, represented some change for the Northwest Territories — never before had a premier served two terms. Continuity with change, then.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from the electoral authorities in Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.