#EveryElectionProject: Saskatchewan

Capsules on Saskatchewan's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Saskatchewan.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1905 Saskatchewan election

Saskatchewan’s first election

December 13, 1905

When the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were created by Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government in 1905, it was a foregone conclusion that a Liberal would be appointed Alberta’s first premier. It wasn’t so obvious who would be the first premier of Saskatchewan.

Frederick Haultain had been the premier of the Northwest Territories (which included modern Alberta and Saskatchewan at the time) since 1897. But he had been at odds with the Laurier government when it came to drawing up the new map in Western Canada. He wanted one gigantic province called Buffalo to be created, and he wanted this province to have greater provincial powers related to resources and education than Laurier was ready to provide.

Worst of all, though, was that Haultain was a Conservative.

Though he tried to administer the territory in a non-partisan way, he had aligned himself with the federal Tories on a number of occasions. That was enough to tip the balance in favour of a Liberal. That would be Walter Scott, an MP who had been chosen to lead the Saskatchewan Liberals into their first provincial election campaign.

“The new Premier was a prominent Western Liberal,” according to The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs for 1905, “a member of Parliament for Assiniboia since 1900; a journalist by profession and only 38 years of age; and President of a Company owning the Regina Leader and the Moose Jaw Times. Personally, he was a man of capacity and had been recognized for some years as a coming politician.”

He didn’t have the experience or the reputation of Haultain, though. Sticking to his non-partisanship, Haultain formed the Provincial Rights Party. What Haultain saw as a party fighting for respect for the constitution Scott termed a “party of agitation and law suits.”

Both the Liberals and the Provincial Rights Party adopted similar planks in their platform related to the ownership of public utilities and the building of railroads and schools. But Haultain’s platform also included demands for full provincial autonomy equal to that of other provinces. To do so, Haultain would take the Dominion government to “the highest Court of the Empire."

“The issues involved are so momentous to the future well-being of the country,” stated the Provincial Rights Party platform, “that it would be unpatriotic and detrimental to the future advancement of the Province and country to entrust their decision to the result of a contest on Dominion party lines.”

Newly installed as premier in September, Scott set up his government and delayed the election until after Alberta went to the polls (the fault of the harvest, of course). The Liberals’ sweeping victory in that province helped build momentum for the party in Saskatchewan, and in the meantime Scott used the opportunity to tour the province by train and buggy, delivering speeches.

The Liberals had much working in favour, including a good slate of speakers, an effective organization, federal patronage and that “everybody was feeling satisfied over the bountiful harvest and good times.”

Scott made his ministers run in difficult ridings in order to help tip the balance in the Liberals’ favour, and attacked Haultain and the Provincial Rights Party as more concerned with litigation and constitutional matters than improving the lives of Saskatchewan people. The Liberals, according to their slogan, were for “Peace, Progress and Prosperity.”

The legislation that had created Saskatchewan, Scott argued, was “not only passably good, but abundantly good; that is to say they are practically wise, constitutionally sound, and financially, especially, favourable.”

And while Scott had obtained promises from Laurier that the Canadian Northern Railway would continue to Regina and that the federal government recognized its responsibility in building a railroad to Hudson’s Bay, Haultain, according to the Liberals, was in the pocket of the hated Canadian Pacific Railway, which had been exempted from paying taxes to the local government.

Against this barrage, Haultain had less to work with. He didn’t have the same roster of prominent speakers and his organization was not nearly as strong, though he did point to Liberals running as Provincial Rights candidates as proof of his non-partisanship.

A divisive issue on the campaign trail was the existence of separate denominational schools, and that the Autonomy Act that created the province had mandated they be allowed in Saskatchewan. Haultain, while not explicitly coming out against separate (and predominantly Roman Catholic) schools, said that it should be up to Saskatchewan, not Ottawa, to decide how its educational system should work.

That got him support from Protestants and Orangemen, but not Archbishop Langevin of St. Boniface, whose territory included the new province. He endorsed Scott and attacked Haultain. In a tit-for-tat exchange of public letters, Haultain charged that “the Educational Clauses of the Autonomy Bill are the result of a conspiracy, conceived at Ottawa, against the rights and liberties of the Province and now being aided and abetted by Mr. Walter Scott and his political associates”

The result of the campaign was tight, with the Liberals winning 52.3% of the vote against 47.5% for the Provincial Rights Party. The seat results were more lopsided, however, with Haultain’s party winning nearly all of its nine seats in the southeastern corner of Saskatchewan. The Liberals won most of the rest.

Though 17 Liberals were declared elected, one of those victories was rescinded after the fact. Peter Tyerman was declared the winner in the riding of Prince Albert, beating the Provincial Rights candidate Samuel Donaldson by 93 votes. But there was a problem — 151 of Tyerman’s votes had come from three poll divisions, all of which delivered zero voters for Donaldson. A subsequent investigation found that those votes were “bogus”, as “there was not sufficient (if any) persons entitled to vote at said Polls Nos. 24, 25 and 26, to offset the majority of the valid votes cast at the election for Mr. Donaldson in the polls which were validly held.” Two years after Donaldson had won, he was able to take his seat in the legislature.

The Liberals lamented that Haultain and his supports had tried to “arouse class and religious prejudice” during the campaign — not a wild claim when one of the slogans became “Haultain or Langevin”. The Conservatives blamed corruption and “the misuse of naturalization papers”.

Haultain would stay on to try to lead the Provincial Rights Party to power in future elections, but when he failed and resigned so did the pretense of non-partisanship. Once Haultain was gone, the Provincial Rights Party became the Saskatchewan Conservative Party, to the shock of no one.

The 1905 election would be the first of Scott’s three victories as leader of the Liberals, and the first of a string of Liberal victories that would see the party govern Saskatchewan for nearly all of its first four decades as a province.

1908 Saskatchewan election

Walter Scott goes 2-0

August 14, 1908

Early elections in Saskatchewan and Alberta were relatively easy ones for the Liberals to win. Voters in those new provinces had never had a government of any other hue. Being an incumbent with no predecessor had its perks.

Walter Scott was one of those Liberals in Saskatchewan. Appointed the first premier while Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals ruled in Ottawa, Scott won the first election in 1905 with ease. As the province continued to develop and grow, things were going well enough that Scott called his second election ahead of schedule, dissolving the legislature on July 20, 1908.

The province had grown so much that the legislature had increased in size from 25 to 41 seats. It was one of the reasons used to justify the early election call. Another reason, which Scott denied, was that Laurier was planning an election for later in 1908, and wanted to gauge public opinion in Western Canada.

One of those making that charge was Frederick Haultain, still leader of the Provincial Rights Party. Leading what was the Conservative Party in all but name, Haultain had run the territorial administration before the creation of the province. In 1905, he was a man with a governing record. By 1908, he was just an opposition leader.

But “his work during a period in Opposition had retained the respect of the public,” according to the Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, “his reputation for honesty and high character was general, his faculty of speech excellent, with just that touch of humour which goes far in a politician.”

On the other hand, “Scott was a shrewd and aggressive politician, thoroughly versed in Western ways and political conditions, a man of the people, personally popular, and in close touch with the powers at Ottawa.”

Scott went to the people with a program for more support for the agricultural sector, free textbooks for students and the continued extension of railway lines and the province’s telephone network. He was pitched as “the man who does things”, a Liberal who could work closely with Laurier’s government in Ottawa to deliver for Saskatchewan.

The premier also wasn’t afraid to throw a little mud.

In Regina, he attacked the Provincial Rights candidate H.W. Laird. “I make the absolute charge the Mr. Laird was a grafter when he was in the [municipal] Council;” he said, “and let him take me to Court, I will prove the charge.”

Laird did, taking Scott to court over charges of libel. He staked his local campaign on winning the case, saying he would resign if Scott’s charges were later proven to be true. The trial was held only after the election. It was all moot, anyway — Laird lost his bid for a seat, as well as the libel suit.

Both Scott and Haultain mounted extensive speaking tours across the province. The Provincial Rights leader admitted he couldn’t get the same deal out of Laurier as Scott could, but suggested that Saskatchewan voters would be smart to put his party in power in case Robert Borden’s Conservatives formed government after the next federal election.

Haultain was also big on railway development, wanting to build a government-owned railway to Hudson’s Bay with the help of Alberta and Manitoba. He also promised “no direct Provincial taxation except on corporations and railway earnings and on speculators’ lands in unorganized districts”, and was far more supportive of government ownership of things like telephones and grain elevators than Scott’s Liberals.

The message to voters from the Provincial Rights Party was a simple one, as laid out by the Regina Standard: “Vote for Haultain and the Hudson’s Bay Railway—to be built as a Western enterprise and paid out of our natural wealth. A vote for Scott means that a private company will own the road, but the people will pay for it.”

It was a message that was having some resonance amongst voters, and the Liberals were nervous they might lose a few seats.

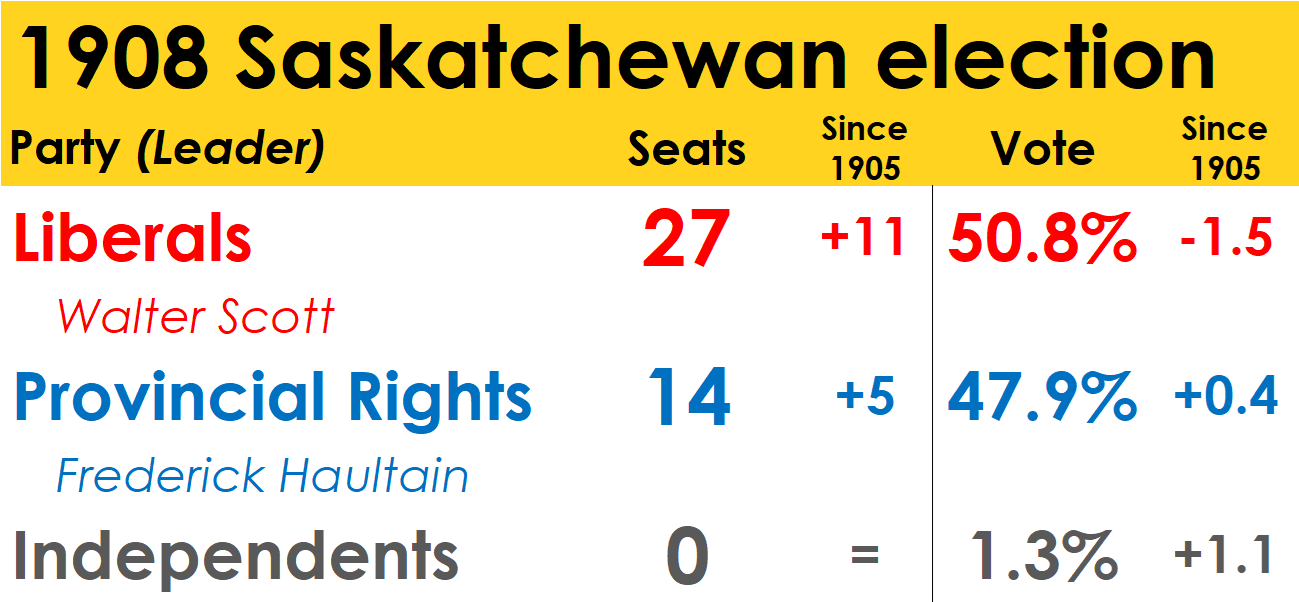

The expanded legislature masked what were some Liberal losses. Though the party won 27 seats, an increase of 11 over the last election, they dropped 1.5 points in popular support and saw two key cabinet ministers, William Motherwell and James Calder, go down to defeat in their own ridings.

(They’d find their way back to the legislature when two successful Saskatchewan Liberals resigned their seats to run for Laurier’s Liberals later that year.)

The Provincial Rights Party saw a small increase in its vote to 48% and won five more seats, finishing with 14. Three of their gains came at the expense of Liberals in the northeast, along with rural ridings north and south of Regina.

But another majority government for Scott and the Liberals meant the end for Haultain and the so-called Provincial Rights Party. It adopted the Conservative name after Haultain stepped down as leader, though it didn’t improve its electoral record. The Liberals would keep winning in Saskatchewan for another 20 years.

1917 Saskatchewan election

Passing the torch in Saskatchewan

June 26, 1917

Over the first few years of Saskatchewan’s history, the Liberal Party under Premier Walter Scott was a dominant force, steering the province through its initial growing pains.

In Saskatchewan Premiers of the 20th Century, Ted Regehr wrote that “while careful not to get ahead of public sentiment, Scott took pride in the passage of socially progressive but controversial legislation on issues such as temperance, votes for women, property rights of wives and widows, and improvements in the province’s educational system. That approach had been endorsed by the voters in three successive elections.”

Scott and the Liberals started to encounter some resistance as the Great War was raging in Europe. There were charges of corruption against his government and agitation against separate schools in Saskatchewan, particularly in the context of a conflict where the enemies were Germany and Austria-Hungary, whose emigrants had come in large numbers to the Prairies before the outbreak of the war.

The premier’s health was also in delicate shape. Scott, the province’s first premier in 1905, finally decided to resign in 1916. He was replaced by William Martin, a Saskatchewan Liberal MP.

Martin effectively nullified some of the challenges facing his new government. A Presbyterian, Martin was less confrontational on the schools issue and swiftly expelled those Liberals MLAs accused of corrupt practices in a series of royal commissions that otherwise exonerated Scott and members of his cabinet.

The Saskatchewan Liberals, whose slate of candidates in 1917 would include a majority of farmers, had also taken precautions that protected them from the rise of agrarian populist parties in other parts of Canada. Adopting farmer-friendly policies, the Liberals in Saskatchewan co-opted the farmers’ movements. The Non-Partisan League ran a few candidates in the campaign but would make little headway. While Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario would soon elect farmers’ governments, Saskatchewan wouldn’t. Its farmers were already in the halls of power.

Once the writs were dropped for a short 24-day campaign, Martin and his top cabinet ministers toured the province, extolling their government’s record and progressive policies and accusing the Conservatives of trying to foment ethnic strife in the midst of a war.

They were not entirely wrong about that — the Conservatives advocated for English-only education and received the support of organizations like the Orange Order and the National British Citizenship League, which called for “protection of British rights against the encroachments upon the same by aggressive aliens”.

But the Conservatives had largely alienated the immigrant vote and was ineffective at appealing to the mass of the province’s farmers. Even the Regina Post and Saskatoon Star, two Conservative-affiliated newspapers, endorsed the Liberals. They did, however, suggest that Conservative leader Wellington Willoughby was a good man to be premier — but that he could wait another five years.

The complicated dynamics of the vote were neatly summed up in the Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs for 1917:

The parties at home were trying to hold, in one case, or not to antagonize too strongly, in the other, a large foreign vote; the Farmers, closely organized as Grain Growers’ Associations, etc., were sure of their strength and pretty generally were for the Government which had given them much good legislation; the Non-Partisan League appealed, however, as an American and independent organization to American farmers, of whom there were many, and was not very friendly with the Grain Growers; there was no Reciprocity issue as in 1912 and the Conservatives, therefore, had a better chance with the farmers; the Soldiers’ vote at home and abroad was expected to go largely Conservative on the Education and Alien issues and the alleged injury of not allowing those at the Front to vote at the same time and for candidates in their home constituencies; the Woman vote was an unknown element which refused to take sides and every effort was made by both parties to win it — with the advantage to the Government which had given women the vote.

There was some criticism from the Conservatives that the Liberals had decided to give soldiers fighting overseas their own representation in the legislature, rather than having the votes counted in their home constituencies, for their own partisan advantage. But the results of the election were clear enough that it likely made little difference.

The Liberals’ share of the vote was virtually unchanged from 1912 at just under 57%, but the drop in the Conservative vote of nearly six points, coupled with an increase in the size of the legislature, resulted in a boost in the Liberal caucus from 45 to 51 seats.

The Conservatives managed to win just seven seats on 36% of the vote, two of their wins coming in the urban seats of Saskatoon and Moose Jaw, then of similar size. Regina, the biggest city in the province, was won by the Liberals.

Three non-partisan soldier representatives were elected later that year.

After the results were in, the Conservatives blamed the so-called “foreign” vote, particularly those cast by women, claiming that had the soldier vote been cast for candidates in their own home constituencies the margin between the Liberals and Conservatives would have been far narrower. It was a debatable claim, as the Liberals received nearly 40,000 more votes than the Conservatives and only 30,000 soldiers serving in Europe were eligible to vote. Not all of them would have backed the Conservatives, as the Liberals were not opposed to conscription — an issue that would become more important in the federal election held later that year.

The Liberals had won another election, kept the agrarian populist and immigrant votes largely to themselves and neutralized the Conservatives’ appeal to nativism. That strategy would serve them well for another decade, but the seeds of a future Conservative victory in Saskatchewan had been planted.

1934 Saskatchewan election

Saskatchewan’s Conservative experiment ends abruptly

June 19, 1934

Saskatchewan’s first experience with Conservative government was a short one and, for the party’s future prospects, ill-timed.

From the province’s entry into Confederation, the Liberals were dominant. They were the party of the established farmers, the linguistic minorities and the new arrivals.

They had also become the party of James Gardiner. First sworn-in as premier in 1926, Gardiner was a party man, head of the so-called ‘Machine’ that won election after election for the Liberals. He was an astute political strategist, seeing the rise of farmers’ movements elsewhere in Western Canada and heading them off. Alberta had been taken over by the United Farmers and Manitoba had a Progressive government, but Saskatchewan remained staunchly Liberal throughout the 1920s.

But the Liberal dynasty came to an end in 1929, when Gardiner’s Liberals were reduced to a minority government. J.T.M. Anderson had managed to rally the anti-Liberal opposition behind his Conservatives, teaming up with Progressives and Independents to form a coalition government — which he termed a ‘Co-operative Government’ — after the election.

Anderson also tapped into a strain of xenophobia that was gaining more traction in Saskatchewan, fomented by the local branch of the Ku Klux Klan. As there weren’t many racial minorities for the KKK to target in the province, their ire was instead aimed at francophones, Catholics and immigrants from eastern Europe.

The Conservatives rode this wave, pledging to end sectarian-religious and minority-language schools and reducing immigration from outside Great Britain. The Liberals retained the Catholic and immigrant vote in 1929, but the more established Protestant communities of British or Scandinavian extraction swung to the Tories.

The early years of the Co-operative government dealt swiftly with these issues, ending sectarian schools and working with R.B. Bennett’s Conservative government in Ottawa to align their immigration policies.

But then the dual disasters of the depression and drought struck Saskatchewan.

Before long, emigration from Saskatchewan was the greater issue than immigration to the province. The population had grown from 758,000 in 1921 to 922,000 in 1931, but it fall back below 900,000 by the time of the next census in 1941. Markets and crops dried up and farmers had no option but to seek relief from government, whose spending on supports for Saskatchewan’s struggling population quickly equated to nearly all the government’s other expenditures.

Anderson and the Saskatchewan Conservatives were no better able to deal with the Depression than governments in the rest of the country, including the increasingly unpopular Bennett government in Ottawa. Anderson was also faced with internal dissension, as his co-operation with Progressives and Independents angered some members of the party. David Johnstone, the party’s president, slammed the door on Anderson and he and his ‘True Blues’ became ardent critics of the Conservatives, eventually endorsing the Gardiner Liberals as the lesser of two evils.

Another new challenger had risen in the form of the Farmer-Labour Party, created in 1932 with the fusion of the Saskatchewan Section of the United Farmers of Canada and M.J. Coldwell’s Independent Labour Party. Coldwell would lead the new faction — which included two of the Progressive MLAs backing the Anderson government — and it would join the new Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in short order, changing its name to the CCF in time for the next election.

Anderson waited until the end of his constitutionally-permitted five-year term before finally dissolving the legislature on May 25 and setting the election date for June 19, 1934. This time, the Conservatives would put up a common front. Most of the Independents elected in 1934 would run as Conservatives, as would a few of the Progressives. That party didn’t put up any candidates, with only the Liberals, Conservatives and Farmer-Labour putting up a full or nearly-full slate.

Anderson ran on his government’s record, hardly an enviable task in the midst of the Great Depression. The Conservatives had not been hard-hearted and had tried to provide relief to the population, but the province had been ravaged and the Anderson and Bennett governments were the scapegoats.

Their campaign was also not nearly as an energetic or focused as that of Gardiner’s, who took aim at both the Conservatives and Farmer-Labour, which Anderson largely ignored.

“The C.C.F. will take your earnings,” one Liberal attack went. “The Conservatives will spend your earnings. The Liberals will increase your earnings.”

Gardiner pulled out all the stops, ensuring that Saskatchewan Liberal MPs made the trip back home to campaign, even though the House was sitting at the time. Coldwell could only be a part-time Farmer-Labour leader — the school where he served as principal didn’t give him leave, so he could campaign only on weekends — but he did get a boost from J.S. Woodsworth, the leader of the national CCF, who addressed a rally in Saskatoon a few days before the vote.

The headwinds were just too strong against Anderson. His support of Co-operative Government meant he never made serious efforts to develop partisan riding associations across the province, leaving the Conservatives in worse shape than even the newly-formed Farmer-Labour Party. That flirtation with Progressives and Independents made him no friends with the beleaguered national Conservative organization, but Anderson’s party affiliation with the unpopular government in Ottawa gained him no favours in downtrodden Saskatchewan. Though those within the party still predicted re-election by the end of the campaign, Anderson and the Conservatives were doomed.

They were completely run out of the legislature. Their vote dropped by only 10 percentage points to 27% but it cost them all of their seats. No Conservative or former Independent or Progressive who ran under Anderson’s banner was re-elected.

The Liberals saw their support increase by only two points to 48%, but it was enough to win them 49 seats on election day (the legislature had been reduced in size to save money). The Liberals increased their tally to 50 after a deferred election in Athabasca between two Liberal candidates — no other party bothered to put up their own man.

Farmer-Labour formed the official opposition with five seats, taking 24% of ballots cast. All five of them, however, were in the rural parts of the province, with four of them along the western border with Alberta. Coldwell failed to win a seat in Regina, a loss he credited to “Booze, Boodle and Bigotry”.

Farmer-Labour was, after all, more Farmer than Labour. It was the Conservatives, not the FLP, that finished behind the Liberals in the two-member urban districts in Regina, Saskatoon and Moose Jaw. The cities and nearly all of rural Saskatchewan was swept by the Liberals.

“Gardiner listened to the results at the farm, and when victory was certain flew to Regina,” wrote Norman Ward and David Smith in Jimmy Gardiner: Relentless Liberal. “There he was met by cheering crowds who lined the streets as a motorcade, complete with pipe band, took him to the legislative building.”

The Liberal dynasty had returned to Saskatchewan, and the result was seen as a good omen for Mackenzie King’s federal Liberals as it coincided with a victory by the provincial party in Ontario on the very same day. Done-in by the Depression, the Conservatives were on their way out. They wouldn’t be back in office in Saskatchewan for nearly 50 years.

1938 Saskatchewan election

Patterson wins, the CCF arrives

June 8, 1938

The 1930s were a time of tumult in Canadian politics, as the Great Depression upended governments and new political movements were on the rise. In Saskatchewan, the election of 1938 pitted the Liberal government of W.J. Patterson against two of those new movements — and a future prime minister.

Though Patterson was only heading to the polls for the first time as premier and Saskatchewan Liberal leader, the province had been governed by his party for 28 of the 33 previous years since Saskatchewan was created in 1905.

That sole exception was the 1929-1934 interregnum of James Anderson, itself the product of a tumultuous election when the Conservatives reduced the Liberals to a minority (with a little help from the Ku Klux Klan). Anderson was then able to govern in a coalition with Independent and Progressive members of the legislature, and was shortly rewarded for his efforts with the a stock market collapse and a drought.

The Conservatives were swept out of power in 1934 (literally, they didn’t win a single seat) and James Gardiner returned to the premier’s office. He didn’t stay long, however, as he made the jump to federal politics to join Mackenzie King’s cabinet in 1935.

Patterson, the minister of natural resources (and telephones), was chosen as his replacement by caucus in part because his chief opponent, T.C. Davis, decided to vote for Patterson rather than himself, and lost by a single vote.

In many ways, though, Gardiner remained the force behind the Saskatchewan Liberal Party. Patterson, an unflashy politician, left the organization of the party to another minister, C.M. Dunn, under the watchful eye of Gardiner, who would also hit the hustings and campaign for his former provincial party.

Against the Liberals were arrayed a motley crew of opposition parties, the foremost being the new Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, whose members had waged the last campaign under a Farmer-Labour banner (and would eventually become the modern NDP).

With just five seats, the CCF formed a small but effective official opposition under George Williams, who ran the party almost single-handedly. There were divisions within the CCF, however, as Williams did not see eye-to-eye with either M.J. Coldwell or Tommy Douglas, the party’s two Saskatchewan MPs in Ottawa. There was also indecision on how to move forward against the Liberals, with the CCF negotiating with both the Conservatives and Social Credit about where to run candidates. In the end, the CCF ran just 31 in Saskatchewan’s 52 ridings.

Social Credit was still a newish phenomenon in 1938, though it had been in power for three years in the neighbouring province of Alberta under the erratic William Aberhart.

Based on a monetary theory developed by a British author that was not entirely understood by the evangelical preacher and new premier of Alberta, Social Credit imagined a monetary system that would ensure the amount of money in circulation would equal the value of everything being produced. It was a theory that didn’t quite make sense and Aberhart’s interpretation of it led to provincial legislation being disallowed by the federal government and the distribution of government credit derided as “funny money”.

While the shine was starting to wear off Social Credit in Alberta by 1938, the party was still a force to be reckoned with and Aberhart looked to Saskatchewan as his next conquest. Resources were poured into the province from Alberta and the Socred campaign in Saskatchewan was run from Edmonton, with Aberhart’s No. 2 (and future premier) Ernest Manning put in charge of organizing it.

Aberhart spent a week in Saskatchewan speaking to enormous crowds and railing against “the money power” and “financial tyranny”. In all, the Socreds put up 40 candidates in Saskatchewan approved by the party in Alberta.

Finally, there were the Conservatives, now under the leadership of Prince Albert lawyer and future prime minister John Diefenbaker. Broke and seatless, Diefenbaker could do nothing more than run 24 candidates and wage a campaign that was largely ignored. He complained about the Liberals’ machine politics and patronage, saying that “government inspectors … are so thick they have been ordered to wear a distinctive ribbon in their lapels so they will not go around asking each other for their vote.”

In the end, the fight was primarily between Patterson’s Liberals and the two upstarts. The governing party warned against the dangers of Social Credit’s crackpot theories and the creeping socialism of the CCF.

After nearly a decade of suffering, the province was not quite in the mood for more uncertainty. It was still reeling from drought and the Depression, with half of the provincial budget in 1935-35 going to relief.

The weather improved in early 1938 and the prospects were good that the drought was coming to an end. Patterson promised to continue relief payments while continuing to invest in the education system, the highway network and various medical programs.

Patterson and friendly editorialists cast the fight as one between a steady, stable and reliable Liberal administration and an array of new parties pushing new, untested and dangerous ideas, none of which could form a government without the help of one or more of the other parties. In short, a Liberal defeat was a recipe for instability and recklessness just when Saskatchewan was getting back on its feet.

Though the Liberal majority was reduced, Patterson’s pitch worked. The Liberals captured 45% of the vote, down three points from 1934, and won 38 seats. That was down 12 seats from the last election, but the Liberals nevertheless nearly swept the rural ridings in the west and the southeast while winning the two-member urban ridings in Regina, Saskatoon and Moose Jaw.

The CCF captured 19% of the vote, down five points from the Farmer-Labor performance of 1934, but gained five seats. It took on the role of the official opposition once again, winning nearly all of its seats in the rural east of the province.

Social Credit failed to make a breakthrough, winning 16% of the vote and just two seats, though one of them was Melville, the seat of Liberal organizer Dunn.

Two “Unity” candidates — an odd amalgamation from various parties, including the CCF, Conservatives who were opposed to the Liberals — were also elected, while Diefenbaker’s party was shut out again, its vote dropping 15 points to just 12%. Undaunted, Diefenbaker would look to federal politics for his future.

Patterson celebrated the victory, saying “an invasion from an adjoining province has been repelled and a sane, business-like constructive program has been chosen in preference to theoretical and theatrical proposals.”

Social Credit would not gain a beachhead in Saskatchewan. But the Liberals would soon meet their Waterloo. When the province next headed to the polls in 1944, Patterson would go down to defeat at the hands of the CCF, now under Tommy Douglas. The 1938 election would be the last the Liberals would win in Saskatchewan for another 26 years.

1967 Saskatchewan election

Ross Thatcher wins again

October 11, 1967

A political dynasty went by the wayside in the 1964 election as Ross Thatcher’s Liberals took power in Saskatchewan, ending the 20-year reign of the CCF. After two decades of North America’s first socialist government, Thatcher promised to make Saskatchewan “the greatest private enterprise province in Canada”.

But Thatcher, a former CCFer himself, knew the electoral limits of his appeal to slay socialism and so he promised to maintain the ground-breaking Medicare system that had been introduced by Tommy Douglas’s government and brought to fruition by his successor, Woodrow Lloyd.

A little over three years after Thatcher’s upset win, the Saskatchewan economy was buzzing. Unemployment was at rock-bottom levels. In 1966, Saskatchewan no longer qualified for equalization payments and became a “have” province, buoyed in part by the explosion of the potash industry. Though the Liberals’ short term in office was not responsible for all of these positive changes, Thatcher was more than happy to take full credit for Saskatchewan’s success.

And to try to capitalize on it. There were warnings of a recession looming, so Thatcher decided to go back to the polls while the going was good. He said that “a new mandate is needed … to assure potential investors in Saskatchewan of a political climate which is essential to encourage continuation of our private enterprise progress.”

The Liberals presented an unambitious program, promising little more than “sound government” and “down to earth common sense” in its administration of Saskatchewan. Thatcher also renewed his call to Socreds and Conservatives to continue backing the Liberals to keep the CCF out, as they had done in 1964.

That party’s name was in the process of changing, but Woodrow Lloyd was still at the helm. The federal New Democrats had been formed in 1961 and were being led by Douglas, but the CCF brand still had a lot of mythical power in agricultural Saskatchewan, where the labour movement had less sway. The old name would finally disappear shortly after the election, but in 1967 it was still the CCF-NDP.

The party’s platform was far more ambitious than the Liberals’, and Lloyd and the CCF-NDP criticized the government for selling out the province to outsiders and corporations — arguing “that we put people first, and that we make things, production and dollars serve the people.”

Lloyd made a play for younger voters, pitching significant investment in post-secondary education. He also had a renewed organization behind him, as he had spent the last three years getting the party into better shape and attracting new candidates, including a young Roy Romanow.

But the going would be tough for the CCF-NDP, especially as the Progressive Conservatives under Martin Pederson were fading away as a serious contender. Both opposition parties got help from their federal cousins, but while Lloyd got a visit from Douglas, Pederson did not get to share a platform with Robert Stanfield or former prime minister John Diefenbaker.

The Canadian Annual Review for 1967 felt “the campaign was slow and all but devoid of issues and incidents”, but it did have its dark side, according to Dennis Gruending in his biography of future premier Allan Blakeney, who was an CCF-NDP MLA seeking re-election in 1967:

“The campaign became nasty, with the NDP’s newspaper, The Commonwealth, calling Thatcher a tyrant. He took the bait, waving the newspaper at rallies and shouting, neck veins bulging, that the socialists were running a campaign of malice, hatred, and fear. There was also an NDP whisper campaign on the doorsteps which accused Thatcher, a diabetic who periodically had to be hospitalized, of being an alcoholic.”

But the bottom line was that things seemed to be going pretty good in Saskatchewan. The economy was diversifying, incomes were up and unemployment was down. There was little need to turf a one-term government that appeared to be performing well. And while there was a certain charisma to Thatcher, Lloyd was more of a thinker, organizer and policy wonk — not the type to inspire a wave of enthusiasm in the CCF-NDP’s favour.

It turned out to be a close election, just as it had been in 1964, with support for both the Liberals and CCF-NDP increasing. The Liberals finished on top with 45.6% of the vote to the CCF-NDP’s 44.4%. But thanks in part to a new electoral map designed during the Liberals’ time in office, the governing party increased its seat total by three to 35. The CCF-NDP fell two seats to 24.

The Liberals’ edge over the CCF-NDP was felt primarily in the rural ridings of southern Saskatchewan, but the party was also able to win a few seats in Regina and Saskatoon.

Pederson and the PCs, however, were wiped out as their vote was cut nearly in half.

Lloyd decided to stay on as leader even though he had lost his second consecutive election. Internal divisions would eventually lead to his resignation a few years later ahead of the 1971 campaign.

That would prove to be a tough one for Thatcher the Liberals. Shortly after winning an election on a message of continued prosperity for Saskatchewan, the Liberals brought in an austerity program in anticipation of the economic troubles that would hit the province — troubles that would catch up to and ultimately defeat Thatcher’s Liberals in the next election.

1970 Saskatchewan Progressive Conservative leadership

The Saskatchewan PCs reject separatism

February 28, 1970

John Diefenbaker liked to joke that, in his younger days, the only thing protecting Conservatives in Saskatchewan were the game laws.

Of course, that was no longer the case once Diefenbaker became leader of the federal Progressive Conservatives. Under him, the party swept or nearly swept the province in every election between 1958 and 1965.

But it was still tough to be a provincial Tory in Saskatchewan. The party hadn’t governed since the Great Depression (when, to its shame, one of its important allies was the Ku Klux Klan) and failed to win a single seat from 1934 to 1960.

Diefenbaker’s success, however, was beginning to rub off on the provincial PCs — at least a little. The party underwent a small revival under Martin Pederson when, in the 1964 election, Pederson finally won a seat for the PCs and lifted them to 19% of the vote. Any hope that Pederson could lead the PCs back to respectability were dashed, however, when they were shut out again in 1967 and lost nearly half their vote share. Saskatchewan was a two-party province, and it was Ross Thatcher’s Liberal Party, in government since 1964, that got the votes on the centre-right.

In 1968, Pederson gave up and the PCs went without a permanent leader for nearly two years. It wasn’t a much sought-after job.

A leadership convention was finally called for February 28, 1970. But it was hardly much of a race — or a convention.

As described by Dick Spencer in Singing the Blues: The Conservatives in Saskatchewan, it was an “odd-ball convention [that] was a small, distracted mix of federal and provincial Tories, Social Credit remnants and disaffected Liberals”.

There were only two candidates. The favourite was Ed Nasserden. He was first elected as a PC MP in the Diefenbaker wave of 1958 for the riding of Rosthern, and held the seat for the Tories until his defeat in 1968.

His rival for the job was Marlin (Marlyn or even Martin, spellings differ in newspapers) Clary, a businessman from Leader.

According to The Phoenix, “Mr. Nasserden’s program and policy recommendations were more conservative and traditional than those offered by Mr. Clary.”

That’s because Clary was a separatist. Telling Saskatchewan Tories that the voices of Western Canadians could not be heard in a parliament that had more seats for Toronto and Montreal, he wanted to see economic separation for B.C., Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. That didn’t have to mean political separation (though it wasn’t clear how it couldn’t), but Clary was trying to take the party in a very different direction than was Nasserden.

Robert Stanfield, leader of the federal Progressive Conservatives, didn’t like what he was hearing. Speaking at a banquet held after the convention was over, Stanfield told the crowd of Saskatchewan PCs he was “alarmed to hear how popular the talk of Western separatism has become”. Blaming Pierre Trudeau for fomenting this Western separatism, Stanfield argued that separation would be as bad for the West as it would be for Quebec.

How the 250 delegates voted was not made public, but Nasserden was announced as the winner. Stanfield might have been a little spooked by what he saw at the convention, but Progressive Conservatives would nevertheless not become the Parti Québécois of the Prairies.

Still, Nasserden had a big task ahead of him to make the PCs the main centre-right option for Saskatchewan voters. He thought that merging with Social Credit (which had captured less than 1% of the vote in each of the last two elections) would make that easier, and a negotiation with the Socred leader was worked out. Nasserden hoped his merger could be replicated at the national level.

His scheme fell apart — as did his hopes of making the PCs a viable party again. With a small slate of candidates, Nasserden led the PCs to only 2% of the vote in the 1971 election that brought the New Democrats back to power.

The Tories wouldn’t stay marginal forever, though. Nasserden’s successor, Richard Collver, would lead the Tories back to official opposition status before the end of the decade and Grant Devine would take them back to power in 1982. For a brief moment, though, the Saskatchewan PCs were close to tying themselves to a truly marginal idea: Western separatism.

1970 Saskatchewan NDP leadership

Blakeney defeats Romanow

July 4, 1970

Tommy Douglas is widely remembered as the father of Canada’s universal health care system after first introducing it in Saskatchewan. But it was actually his successor, Woodrow Lloyd, who turned the proposal into law, navigating it through the legislature and facing down the province’s striking doctors.

Lloyd got little thanks for his efforts. When he took his CCF government to the polls in 1964 (the Saskatchewan CCF had not yet followed the national party in adopting the New Democratic moniker), Lloyd went down to defeat against Ross Thatcher’s Liberals. Lloyd just wasn’t the firebrand and charismatic Prairie populist that Douglas was, and he followed up his defeat in 1964 with another in 1967.

Patience with Lloyd within the Saskatchewan NDP (as it was now finally known) had run out in 1970. In the federal convention the year before, Lloyd had voted in favour of a motion put forward by the Waffle that reflected the group’s socialist, radical views, greatly influenced by the anti-Vietnam War politics of American youth.

The motion didn’t pass, but the Waffle was starting to have a big influence within the national party — and the Saskatchewan wing, too. Members of the ‘Old Left’ and more pragmatic centrist wings of the party were not happy, and after a contentious caucus meeting in March 1970 Lloyd offered his resignation.

That put Allan Blakeney in an odd position.

Blakeney had long been a loyal supporter of Lloyd and had been deeply involved in the Medicare file as minister of health. Minutes were not kept, but Blakeney does not appear to have spoken out in defense of Lloyd at the caucus meeting, and the distaste he felt at how Lloyd was forced to resign led him to hesitate to run to replace his old colleague.

But Blakeney had always had his eye on the leadership and he was the first to announce. He had the experience to be leader. Though just 44, he had been a Regina MLA since 1960 and had been named to cabinet by Douglas before he had left provincial politics to take over the federal NDP.

After about a month, another candidate stepped forward: Roy Romanow. Just 30 (though he told the newspapers he was a few years older), Romanow had been first elected in Saskatoon in the 1967 election and was seen as a bright rising star within the Saskatchewan NDP. But he was also seen as representing the centre or centre-right of the party.

“[Romanow’s] campaign was modelled on the new era of television politics in the United States,” writes Dennis Gruending in his biography of Allan Blakeney, Promises to Keep. “He was photogenic, and had an easy way with people. There was a glitz and excitement to his campaign that Blakeney couldn’t match.”

With neither Blakeney nor Romanow being a spokesperson for the left, it was inevitable that other candidates from that side of the party would emerge. There was Don Mitchell, even younger than Romanow, who stepped forward as the unofficial candidate of the Waffle group, pitching public ownership of Saskatchewan’s farmland with a so-called “Land Bank”. There was also George Taylor, a venerable standard-bearer of the Old Left and the Regina Manifesto and a veteran of the international brigades of the Spanish Civil War. Taylor was there to avenge Lloyd’s defenestration.

While Blakeney put the emphasis on experience and Romanow on style, Mitchell focused on policy in the series of town hall debates that took place during the campaign. He might have pulled Blakeney and Romanow further to the left than they would have liked — the two eventually said his Land Bank idea wasn’t so bad after all — but the contest was always going to be between Blakeney and Romanow, between the establishment of the party and a new modern direction.

Some 1,600 people gathered at the Regina Armouries for the vote. The Waffle vs. Establishment battles continued in the contest for party president, and the win by the Establishment boded well for Blakeney. It was a shock, then, when Romanow narrowly emerged as the front runner on the first ballot with 35.3% of delegates’ votes to 33.6% for Blakeney. Mitchell took 22% and Taylor dropped off after taking 9.2% of the vote.

On the second round, Taylor’s votes split nearly evenly between the three other candidates, though Mitchell garnered more than either Blakeney or Romanow. The gap was closed between the leading candidates, and Mitchell dropped off after the second ballot.

Romanow had spoken out against the Waffle and Blakeney was also seen as opposed to the movement, so Mitchell decided to abstain on the final ballot. Taylor, though, tried to gather the old guard of the left behind Blakeney. While a big chunk of Mitchell’s supporters indeed abstained, Blakeney got more than three votes for every vote gained by Romanow on the final ballot, and emerged with a narrow win: 53.8% to 46.2%.

With a little guidance from Douglas, who suggested that his turn would come later (and it would), Romanow urged the convention to make the decision unanimous. Allan Blakeney would be the next leader of the Saskatchewan NDP — and return the party to power in 1971.

1982 Saskatchewan election

A Devine wind sweeps Saskatchewan

April 26, 1982

You could forgive Saskatchewan’s premier, Allan Blakeney, for thinking his odds of winning an election in 1982 were good.

After long being a have-not province, Saskatchewan’s economy was finally booming. Growth was the highest in the country. Unemployment was lower than anywhere else. Resource revenues were pouring into government coffers, allowing it to run balanced budget after balanced budget.

Blakeney had also just played a key role on the national stage in the constitutional negotiations, earning respect across the country.

But if the Saskatchewan New Democrats had been a little more in touch with the mood of the people, they might have realized that the odds of re-election were, in fact, not so good at all.

Blakeney and the NDP had been in power in Saskatchewan since 1971. The province was seen as an NDP stronghold. With the exception of the Liberal government of Ross Thatcher, in office from 1964 to 1974, no one else had governed Saskatchewan since Tommy Douglas’s upset victory as leader of the CCF in 1944.

The political landscape was shifting in Saskatchewan, however. The Liberals had collapsed as a force and it was the Progressive Conservatives who were emerging as the chief rival to the NDP. Achieving government, though, seemed like a long-shot. No Conservative had governed Saskatchewan since 1934.

When Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals announced they would end the Crowsnest Pass freight rate on grain shipments, thereby increasing grain growers’ costs, Blakeney thought he had a winning issue. His government railed against the decision and sent pamphlets to voters across the province. The NDP could play an anti-Ottawa, Western-grievance card as well as anyone else.

On March 29, after announcing another balanced budget that increased spending on social programs but did not reduce taxes, Blakeney set April 26, 1982 as the date for the next election. Before he did that, though, his government brought in legislation prohibiting strikes of essential workers during the campaign in response to a work stoppage by CUPE hospital staff.

While it was meant to avoid any discontent on the part of voters, it had the effect of seriously hurting the NDP’s support among the key labour electorate that was also an important source of volunteers and campaign organizers. Instead of backing Blakeney, CUPE protesters appeared at Blakeney’s events.

The NDP planned to run on its record of a strong economy and governing competency, adopting the “Tested and Trusted” slogan in order to contrast Blakeney’s experience with that of the 37-year-old PC leader, Grant Devine.

An economics professor, Devine had never won anything before he prevailed in the 1979 Saskatchewan PC leadership contest. In fact, he’d lose one more time in 1980, when he failed to secure a seat in the legislature in a byelection.

But Devine proved to be a strong campaigner. With a slogan of “There’s so much more we can be”, Devine made lots of costly promises, starting with getting rid of the provincial tax on gasoline, which he announced on the first day of the campaign.

That set the tone. More promises followed, including a cap on mortgages set at interest rates of 13.25% — the Saskatchewan government would cover anything above that. He also promised to phase out the PST and reduce the income tax, promises that would severely reduce the government’s revenues. But for voters who were worried about sky-high interest rates and felt Blakeney’s government was overly focused on balancing the budget, these promises resonated.

The NDP had miscalculated. The Crowsnest rate wasn’t a good issue. It was seen as out of the province’s hands, a federal issue, and in any case all of the parties were just as against Trudeau’s move as Blakeney was. Even Ralph Goodale, the former Liberal MP and leader of the Saskatchewan Liberals, had come out against it.

As the momentum shifted, Blakeney turned his focus on Devine’s platform, arguing that all of these tax cuts would inevitably lead to program cuts. But when that failed to move the dial, Blakeney tried to match Devine’s largesse with promises of his own.

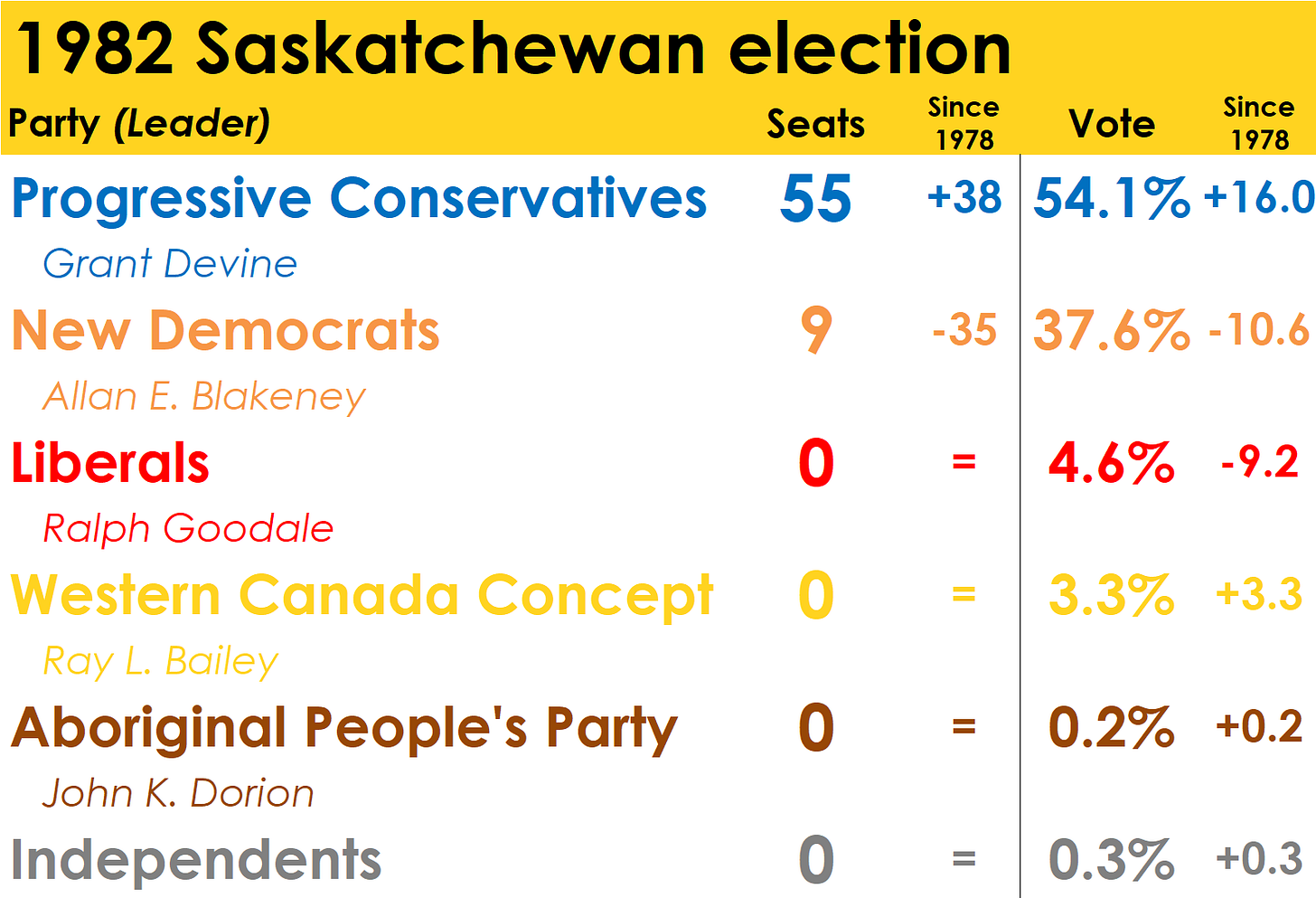

The result was a huge landslide PC victory that surprised even the Tories. The early returns were so good for Devine that a PC government was called in less than 30 minutes.

Devine and the PCs won 55 seats, a swing of over 35 seats in the expanded legislature, taking 54.1% of the vote, a gain of 16 points over the PCs’ performance in 1978.

In that election, the New Democrats had swept Saskatoon and won all but one seat in Regina. This time, it was the PCs who swept Saskatoon and won all but two seats in Regina, an enormous swing that reduced the NDP to just a handful of seats in the rural areas, where the PCs also made significant gains.

The New Democrats won just nine seats and 37.6% of the vote. Up to that point, it was the worst result in the history of the NDP since before the CCF came to power in 1944. It cut a swathe through Blakeney’s cabinet, taking even future premier Roy Romanow down with it.

The slide of the Saskatchewan Liberals continued. They had been shutout in 1978 and were shutout again in 1982, but their 4.6% of the vote marked the first time the party had hit single-digits. They barely finished ahead of the separatist Western Canada Concept, which had hoped to repeat the success of its Alberta equivalent that had just won a byelection in that province. It took 3.3%.

Blakeney, who held on in his own seat, would stay on as NDP leader and improve the party’s position in a rematch in 1986. He’d step aside after that, making way for Romanow.

For the PCs, 1982 would rank as their best result ever. But the costly promises made by Devine during that campaign would leave a legacy of huge deficits during his two terms in office, contributing to the eventual demise of the Tories in the 1990s. The remnants of the party would go on to form the Saskatchewan Party that looks as unbeatable in the province today as Allan Blakeney’s New Democrats seemed to be at the start of 1982.

2013 Saskatchewan NDP leadership

Cam Broten becomes Saskatchewan NDP leader

March 9, 2013

Being opposition leader in Saskatchewan has been a thankless and perilous task over the last few years. Not since 2007 have the Saskatchewan New Democrats had a leader who contested more than a single election, a trend that will continue after Ryan Meili announced last month he’d be stepping down.

In 2013, though, there wasn’t a trend — just one unlucky leader in Dwain Lingenfelter, defeated in 2011. The future didn’t look particularly bright, though, with Brad Wall still enormously popular at the time. But nothing lasts forever, right?

So, with a vacancy at the top of the Saskatchewan NDP, the race was on. And it would turn out to be a pretty demanding one, as candidates faced off in more than a dozen debates throughout the fall of 2012 and the winter of 2013.

For most of the contest, there were four candidates. All under the age of 40, it marked what some called a generational shift for the party.

The (admittedly small) caucus was lining up between two of their colleagues: Saskatoon MLA Cam Broten and Regina MLA Trent Wotherspoon. Also on the ballot was Erin Weir (a future NDP MP) and Meili, who had finished second to Lingenfelter in the 2009 leadership contest and was seen as the candidate furthest to the left.

Weir, however, withdrew from the race in February and threw his support behind Meili, leaving the ballot to just Meili and his relatively centrist opponents, Broten and Wotherspoon.

Despite caucus backing the other two, it was Meili who came out on top on the first ballot with 39%, followed by Broten at 33.5% and Wotherspoon at 24%.

With Wotherspoon being eliminated, his support swung toward Broten by a margin of about 3:2, propelling him to 50.3% of the vote against 49.7% for Meili. Just 44 votes out of the more than 8,000 cast separated Broten and Meili.

Broten would go on to lead the New Democrats into the 2016 provincial election with little hope of victory. I recall that campaign fondly as I was covering it closely for the CBC, travelling to Regina to take part in the election night television special. What I remember most was a pronunciation tip I got from a local colleague: “Broten is your bro, not your bra.”

When it was over, he wasn’t even that — he was defeated in his riding of Saskatoon Westview, memorably losing on the final polling box to be counted. The party captured just 10 seats, one more than in 2011 but on an expanded map that contained three more seats.

Broten’s resignation would result in a re-match of sorts in the 2018 Saskatchewan NDP leadership, as Meili and Wotherspoon faced each other again. Third time was the charm for Meili, as he won the honour to lead the party into the 2020 election — and, unlike Lingenfelter and Broten before him, retain his seat. It wasn’t enough, though, and the Saskatchewan NDP will select his replacement in June in the hopes that, this time, they might land on a winner.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Saskatchewan and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Saskatchewan Premiers of the Twentieth Century, edited by Gordon L. Barnhart

Jimmy Gardiner: Relentless Liberal, by Norman Ward

The Life and Political Times of Tommy Douglas, by Walter Stewart

M.J.: The Life and Times of M.J. Coldwell, by Walter Stewart

Rogue Tory: The Life and Legend of John G. Diefenbaker, by Denis Smith

Promises to Keep: A Political Biography of Allan Blakeney, by Dennis Gruending