#EveryElectionProject: Prince Edward Island

Capsules on PEI's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Prince Edward Island.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1890 Prince Edward Island election

A win that wasn’t a win for long

January 30, 1890

Sometimes, even the closest of elections aren’t the most heated of contests, aren’t decided over controversial issues or don’t feature engaging, charismatic leaders.

Take the 1890 election in Prince Edward Island, for example.

Called for January 30 of that year, it came very shortly after Neil McLeod was sworn in as premier of the small province. He took over from W.W. Sullivan, who resigned from the post in late 1889.

The Conservatives, under Sullivan, had been in power since 1879. McLeod was a member of Sullivan’s cabinet and was relatively progressive for his time, promoting labour-friendly legislation while in office. Though some Conservatives didn’t appreciate this direction, McLeod was nevertheless the only real contender for the job when Sullivan stepped aside.

McLeod’s opponent during the campaign was John Yeo, the leader of the leaders. But according to Frederick Driscoll, writing in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, the Liberal leader “did not announce much by way of policy and campaigned against what [he] thought to be the weak record of the government”.

As would often be the case in PEI politics, McLeod instead touted his party’s links with the government in Ottawa which, in 1890, was still run by John A. Macdonald and the Conservatives.

The 19th century (and into the first decades of the 20th century) was a time of a deeply partisan press — every party had its allied newspaper, and those newspapers often went to war with the newspapers supportive of the opposing party. The Daily Examiner, out of Charlottetown, was no exception. A Conservative-aligned newspaper, the Examiner often railed against whatever charges were being made in the Liberal-aligned Patriot.

But reporting on election day, the Examiner tried to keep things cordial — at first.

“In the city the contest was close and exciting from the beginning,” wrote its correspondent. “The candidates were, personally, very well matched. Few had a word to say against any of them. Each was respected and popular. The contest was between the parties not between the men.”

It wasn’t long before the Examiner cast some aspersions on the means by which the Liberals (or the “Oppositionists”, as they were termed) got their vote out.

“Following their usual tactics, [the Oppositionists] ‘put their best foot foremost,’ and brought early to the polls every floating voter whom they could, by any means, command.”

Of course, the Conservatives wouldn’t stoop to such tactics. And while the Liberals might round-up vagabonds and drifters with the aid of a little booze, the Conservatives got the support of the right kind of people — at least according to the Examiner:

“By two o’clock—after the intelligent voters, who man our workshops and factories, our counting-houses and stores and offices—had polled their votes, McLeod…had obtained an advantage which the Oppositionists, with all their force and ability, and their ‘human devices’, could not overcome.”

The result was incredibly close, with the Conservatives winning 16 seats and the Liberals claiming 14. The popular vote was also nearly evenly divided between the two parties, with little having changed since the previous election of 1886.

A note on sources: Researching early elections is often difficult, as sources (when they can be found) do not always agree and newspaper reports from the time are unreliable. The Wikipedia page for this election, for example, lists both the Liberals and Conservatives as winning 15 seats — perhaps why the 1890 election was often referenced as PEI’s first minority government when Dennis King’s PCs won a minority in 2019. Elections PEI also lists the breakdown as 15 seats for each party in their historical references. But the document includes pencil marks, showing that an elected member recorded as a Liberal was actually a Conservative, which would put the count as 16-14. This is the result listed in several other sources, including the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Other sources refer to the McLeod government as being re-elected in 1890, rather than ending in a tie, and James William Richard, the member corrected by pencil in the Elections PEI document, is listed in the Canadian Parliamentary Companion for 1897 as a Conservative. For that reason, I believe the 16-14 result is the correct one.

McLeod’s narrow majority was not built to last. When Macdonald called a federal election in early 1891, three members of McLeod’s provincial caucus opted to run for a seat in the House of Commons. Two of the three byelections subsequently held to fill these vacancies went to the Liberals, with the third going to an Independent Conservative.

The byelection defeats meant McLeod had lost his majority in the legislature. Losing a motion of non-confidence, he asked for a dissolution, the lieutenant-governor refused, and McLeod resigned. Frederick Peters of the Liberals was asked to form a government and his party would remain in office in Prince Edward Island for another 29 years.

1904 Prince Edward Island election

When the premier’s seat ended in a tie

December 7, 1904

At the turn of the 20th century, the Liberals were well-ensconced at the top of Prince Edward Island’s politics. By 1904, the party had been in power for 13 years and Arthur Peters, installed in 1901, was only the latest in a string of Liberal premiers.

A lawyer “born into what passed for an aristocracy in 19th-century Prince Edward Island”, according to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Peters also happened to be the brother of Frederick Peters, who had governed the province from 1891 to 1897.

That’s not to say that there weren’t challenges for the Liberals in Prince Edward Island. While the province’s economy had been booming in the 1880s, by the 1890s it was stagnating on the edges of a country that was increasingly looking westwards. As fortunes worsened, P.E.I.’s politics turned to how the Island could get a better deal from the federal government.

Representation in the House of Commons was one point of contention. The province’s declining population as a share of the country’s as a whole had decreased its allocation of seats from six to just four by 1903, and Peters was a vocal opponent of Prince Edward Island’s falling clout.

Peters also pushed for P.E.I. to get a bigger subsidy from the federal government. That government just happened to be run by a Liberal prime minister in Wilfrid Laurier, and when Peters called an election for December 7, 1904, he had no qualms arguing that voters would ensure a better deal for P.E.I. by electing a Liberal government in Charlottetown to match the one in Ottawa.

The Canadian Annual Review analyzed the situation facing both the Liberal government and the Conservative opposition.

“Against the Government was the increasing taxation and indebtedness, the prevailing lack of prosperity amongst the Island farmers and leadership of the Conservatives by a young and talented man. As to actual performance the Liberal party had to its credit the abolition of the Legislative Council, or rather its curious amalgamation with the Assembly; the obtaining of some important financial re-arrangements from the Dominion; and the passing of a fairly popular, though not always enforced, Prohibitory Liquor law.”

John A. Mathieson, the young man leading the Conservatives, had hopes for a breakthrough. In the federal election held in early November, the Conservatives had won three of P.E.I.’s four seats. Surely that ‘Dominion’ success would translate over to the provincial sphere, even if Robert Borden’s Conservatives were still on the opposition benches in the House of Commons.

In the words of The Globe’s correspondent in Halifax, “the election was one of the most exciting ever held in the Province, and both parties worked hard, fine weather and good roads bringing out large votes.”

The Liberals brought the most votes out.

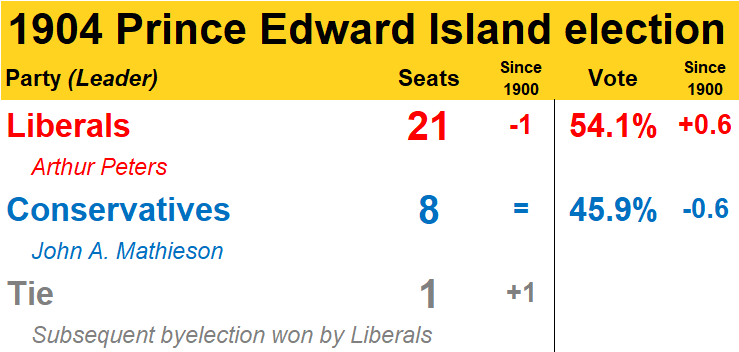

Peters secured a result very similar to the one his predecessor had won in 1900. The Liberals were ahead in 21 seats with 54.1% of the vote, a small gain of 0.6 percentage points. The Liberals swept Prince County, gaining a seat from the Conservatives, but lost one seat in Queens County.

Kings County remained the region of strength for the Conservatives, as it was there that they won seven of their eight seats.

But the most interesting result was in 2nd Kings, where Peters faced a tough fight. When the special votes were counted — people were allowed to vote wherever they held property, even if they had also voted where their primary residence was located — Peters found himself in a tie with the Conservative candidate, Harvey David McEwen, at 515 votes apiece.

While the result kept the premier out of the legislature for a few months, he was eventually able to claim the seat in a byelection called in early 1905. By then, it was agreed that Peters would win by acclamation and McEwen, a prosperous businessman, would go back to his life outside of politics.

But Peters didn’t get to enjoy being premier for much longer — he died of Bright’s disease at the age of 53 in 1908. Mathieson, the “young and talented man”, would eventually get his turn as premier in 1911.

Still, Peters would leave at least one lasting legacy. By 1914, Prince Edward Island was at risk of losing yet another seat in the House of Commons. His campaign to maintain P.E.I.’s representation finally bore fruit when the government of the day decided it would not decrease the number of seats P.E.I. had, but instead stipulate that no province could have fewer seats in the House of Commons than it does in the Senate. That rule has survived for over a century and, today, Prince Edward Island’s seat allocation remains unchanged, and very generous, at four.

1919 Prince Edward Island election

Unrest in the midst of unquestioned prosperity

July 24, 1919

While it included some Liberals, the Unionist government of Robert Borden was primarily Conservative. It had successfully led the country through the First World War but not without leaving a few scars, and when soldiers returned from overseas they expected to be treated like heroes — and that things would change.

That desire for change swept up governments across the country. And many of them were Conservative, regardless of what moniker the Dominion government might have adopted.

The cyclical nature of Canadian elections is not a new invention, and shortly after Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals were removed from office in 1911 following a long stint in power, Prince Edward Islanders did the same with their Liberal government, sweeping in the Conservatives under John A. Mathieson in 1912.

Mathieson and the Conservatives were returned to power in 1915 but with a much-reduced majority. Two years later, Mathieson resigned to take up a judicial appointment and his attorney general, Aubin-Edmond Arsenault, was chosen as his replacement.

Across the aisle from Arsenault sat a veteran of PEI politics. John Howatt Bell had been first elected as a Liberal in the 1886 provincial election. But he was a troublemaker, quarreling with his own premier. He left provincial politics at the end of the century to try his luck at the national level, successfully at first when he ran in a federal byelection but he was defeated in the next general contest. He stepped aside from politics for about 15 years before returning as a Liberal MLA in the 1915 provincial election.

The Liberals hoped to capitalize on Islanders’ discontent with the government. The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs said that the Conservatives had “against them the general unrest and high prices countered, however, by unquestioned prosperity.” Things were going well in Prince Edward Island, but Islanders weren’t feeling it.

The high cost of living — as it was termed even then — and the soldiers’ feeling of ill-treatment upon their return from France were key factors in this “general unrest”. Farmers were also upset with the government, but unlike elsewhere in Canada they failed to organize themselves into a party in PEI. (In 1920, provincial United Farmer candidates would be elected in both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.)

Also at play was sectarian prejudice. The Annual Review said that Arsenault’s Acadian background and Roman Catholicism raised “certain Orange prejudices and grievances”. The Orangemen were also upset that Arsenault appointed an “alleged Sinn Feiner” as secretary to the superintendent of education instead of a Protestant.

Bell and the Liberals ran on providing cleaner and more efficient government, including new investments in education (to promote the “patriotic spirit of the pupils”) and co-operation with farmers’ organizations to lower the costs of goods.

The Conservatives were primarily swept-up in the desire for change. When the election was held in “glorious weather”, in the words of the Charlottetown Guardian, the voters turfed Arsenault and his Conservatives.

The Liberals won 24 seats, a jump of 11 since the previous election. Their candidates captured 51.7% of the vote, up less than two points. But, in a very evenly-divided province, that was enough to ensure a landslide victory.

The Conservatives, down four points to 45.7% of the vote, lost 12 seats, winning only five. Three were on the east coast, one in Summerside and the fifth being Arsenault’s — won in the part of PEI where the province’s francophones are still concentrated to this day.

One Independent was also elected: John Alexander Dewar, a former Conservative who failed to win his party’s nomination, and ran and won in his old district — thanks in large part to the Liberals, who didn’t put up a candidate of their own.

Observers at the time concluded that the soldier and Protestant vote went strongly against the government, while the Guardian blamed the “prevailing unrest and the unlimited promises of Liberal candidates”.

With the benefit of hindsight, however, it is clear that this election result was also part of a broader movement against the Conservatives. The party governed five provinces and in Ottawa at the outbreak of the First World War. By 1921, the Conservatives would be out of office not only in Charlottetown, but in Ottawa and in every other provincial capital across the country, too.

1959 Prince Edward Island election

PEI goes with the flow

September 1, 1959

It was 1959 and Prince Edward Island was in an awkward spot. For the first time since the 1920s, the province had been governed for an extended period of time by a party that also didn’t hold sway in Ottawa.

That had to be fixed.

First elected in 1935 a few months before Mackenzie King’s Liberals returned to federal office, by 1959 the PEI Liberals had been in power for 24 years under four different leaders. The latest was Alex Matheson, who took over in 1953 and won the 1955 election.

Louis St-Laurent was the Liberal prime minister at the time. But in the late 1950s the country had swung to the Progressive Conservatives. John Diefenbaker was elected with a minority government in 1957 and he quickly turned that into a landslide majority the year later. That landslide included a sweep of all four seats in Prince Edward Island.

Undaunted, Matheson sent the province to the polls to boast of his “forward-looking program”, which included free text books for elementary school children, pensions for unmarried women and widows starting at the age of 60 and new trading relationships abroad.

All well and good, but what about Diefenbaker?

All four of his PEI MPs actively participated in the campaign to help elect their provincial cousins, now under the leadership of Walter Shaw.

A 71-year-old farmer and retired deputy minister of agriculture, Shaw didn’t have a seat in the legislature when he took over the opposition PCs, who had just a handful of seats. Matheson obliged Shaw by giving him a bench he could sit on on the floor of the legislative assembly in order to provide some guidance to his MLAs.

Shaw’s platform included the provincial government taking over the portion of teachers’ salaries paid by cash-strapped local school boards. He also pledged support for fishermen and farmers and called the PCs the “party of the causeway”.

Of course, Diefenbaker had merely promised an engineering study about a possible causeway linking Prince Edward Island to New Brunswick, but Shaw made it seem that a vote for the PCs meant a vote for a causeway that was definitely going to happen (it didn’t).

Shaw leaned hard on the notion that PEI needed a friend in the prime minister’s office, saying that Islanders “see the advantage of keeping the province in line with a generous Conservative administration in Ottawa.”

With some degree of self-interest, Matheson said that provincial and federal politics should be kept separate. But his campaign understood they were swimming against the current and instead put a “Matheson government” forward in its advertisements rather than the Liberal brand. Shaw and the PCs, meanwhile, featured Diefenbaker prominently in their advertisements.

It was an unsubtle message, but it worked.

After winning only three seats in 1955, the PCs captured 22 in 1959. The Liberals were reduced to just eight seats, six of them in the southeast corner of the island.

Despite the lop-sided seat result, the voting was actually quite close — the PCs took 50.9% of the vote, a gain of six points since 1955, while the Liberals took the remaining 49.1%.

Bagpipers and 2,500 supporters greeted Shaw for his victory speech, but the results were also greeted warmly in Ottawa. Though they had won a thumping victory only a year before, the Diefenbaker PCs needed some good news. The Liberals had successfully been re-elected on an anti-Diefenbaker message in Newfoundland the month before and new Gallup polling was showing support for the federal PCs slumping. An upset win in PEI improved the mood.

But it wouldn’t last. Diefenbaker’s government became unpopular and was reduced to a shaky minority in 1962. Similarly, Shaw experienced the loss of a few seats when he took Islanders back to the polls that same year. But he held on and in 1966 tried to secure a third mandate for his PCs.

Except by then there was a big problem for Shaw.

The Liberals were back in power in Ottawa.

1968 Prince Edward Island Progressive Conservative leadership

When the premier and opposition leader were neighbours

September 21, 1968

In the 1966 provincial election, Prince Edward Island swung narrowly from the Progressive Conservatives to the Liberals, ending the premiership of Walter Shaw. It wasn’t a decisive defeat, however, as Shaw’s PCs retained 15 seats in the 32-seat legislature.

But by 1968, Shaw had been leading the PCs for over 11 years — and he had his eye on retirement. He’d be turning 81 by year’s end (though the newspapers couldn’t quite get his age right, with three different articles pegging him to be 79, 81 and 83 years old) and he thought that was the time to go.

“I have been under no pressure to retire from the party,” he told the press when he announced his intention to step aside, “but I am at an age when one should consider retirement.”

Somewhat grimly, Shaw pointed out that “no one should hold on until other circumstances, either ill health or death, intervenes. It would be most unfair to stay on until something happens.”

So, the PEI PCs were off to find another leader. Five different candidates came forward, but by voting day only three were still in the running.

They were led by George Key. He wasn’t an MLA and was just 37 years old. But he was the mayor of Summerside, PEI’s second-largest city, and was seen as a centrist Tory.

His main competition was Cyril Sinnott, an internal medicine specialist and the MLA for Kings 5th, which he won by a single vote in the 1966 provincial election. If Key was the moderate, Sinnott was the right-winger (which he himself admitted).

Also on the ballot was Ivan Kerry, the party’s president. With his deep ties in and knowledge of the party, he was seen as a wildcard. But the Charlottetown correspondent for The Globe and Mail felt that Key and Sinnott were the front runners, as they had “launched strong campaigns for the leadership and each cites support from provincial party leaders.”

Over 1,300 voting delegates attended the convention held on September 20 and 21 at the Kennedy Coliseum in Charlottetown. Party members were treated to a speech by Robert Stanfield, who had taken over the national party the year before but was only a few months out from his crushing defeat at the hands of Pierre Trudeau in June 1968 (except in PEI, where the PCs carried all four seats).

But with just three candidates on the ballot, the only question was whether it could be settled on the first one.

It was, with Key winning 691 votes, or about 52% of all those who cast a vote. Sinnott finished second with 36%, with Kerry taking just 12% of the vote.

So, the PCs had their leader — a young man who could take on the Liberal government of Alex Campbell, himself only 34 years old. And who would know how to beat him better than his own neighbour?

Yes, Prince Edward Island is a small place. And it just so happened that George Key shared a lot with Alex Campbell.

“Premier Campbell and I are neighbours in Summerside,” he said in answer to reporters’ questions after his victory. “We attend social functions at each other’s home and we’ve even taken our vacations together. However, I’m afraid I don’t agree with his policies.”

It would’ve been even more awkward to run directly against Campbell in his own riding, so Key opted to run elsewhere. It didn’t help — he would go down to defeat by a mere eight votes as Campbell’s Liberals expanded their narrow majority to a landslide victory in 1970. The PEI PCs would be reduced to just five seats in that campaign, with both Sinnott and Kerry among the defeated, and the PEI Liberals would remain in office for the rest of the 1970s.

1978 Prince Edward Island election

A squeaker, all right

April 24, 1978

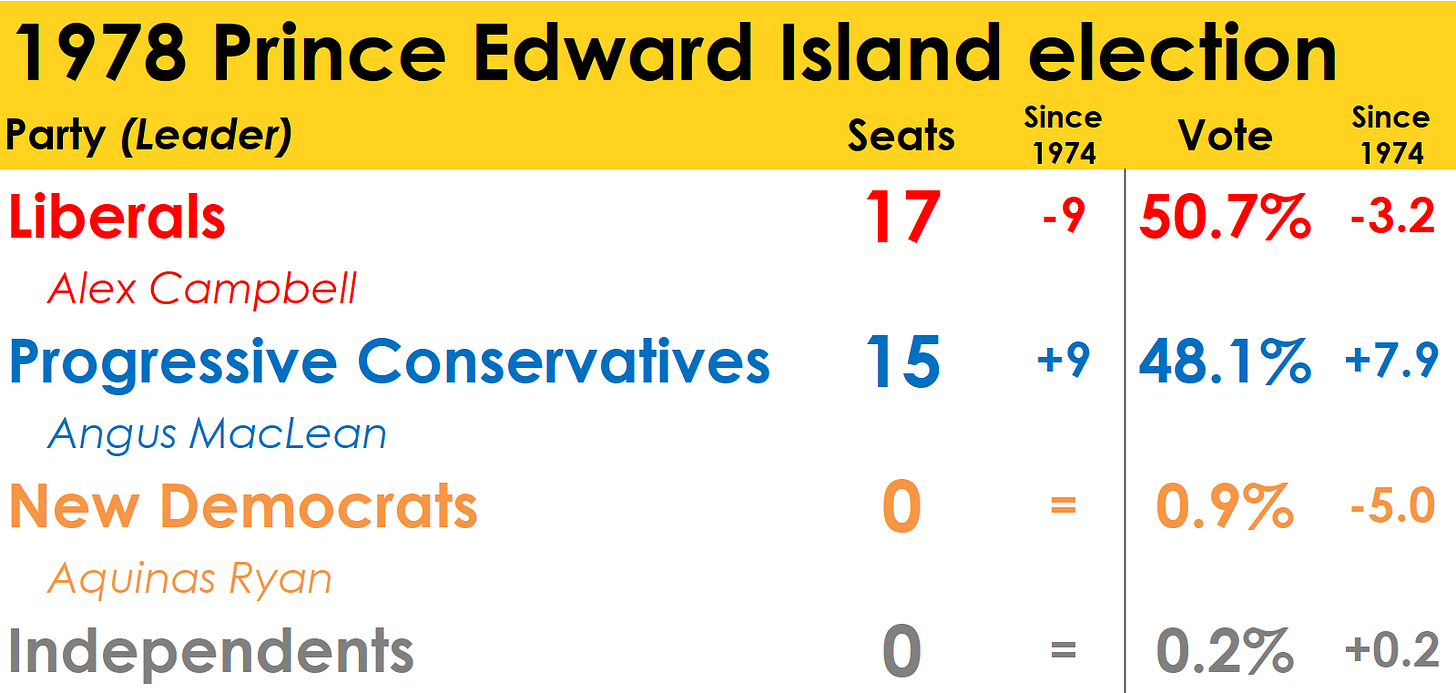

The year was 1978 and Alex Campbell, the premier of Prince Edward Island, was hoping to do something no other premier had ever done before in his province: win a fourth consecutive election.

Though only 44, Campbell was already the longest-serving premier in PEI’s history (a title he still holds today). He had come into office as a younger man in 1966 and had led the PEI Liberals to more wins in 1970 and 1974. But a fourth win in 1978 was not going to be easy.

The party had already lost a couple of seats to the Progressive Conservatives in byelections and the Tories seemed geared-up for the campaign. They had a new leader in Angus MacLean, though he was hardly new to politics.

MacLean had served a quarter century as a PC MP, in the job long enough to have served as fisheries minister in John Diefenbaker’s government. “A politician without flair or a sense of style,” in the words of Martin Dorrell in the Globe and Mail, MacLean was “a reluctant speaker and a man who had never been able to dispel suspicions that he had returned to the province to retire.”

But return he did, taking over the provincial party’s leadership in 1976 and getting himself into the legislature in a byelection. The Liberals were confident they could beat MacLean (the contrast in age between the two leaders was stark) but Campbell nevertheless recognized that “no one has this in the bag.”

The Liberals presented their budget and shortly thereafter dropped the writ. Campbell wanted to continue his work diversifying the economy, largely with the help of federal funds from the Liberal government in Ottawa. New industries would bring 2,000 jobs to the province, cutting unemployment by half.

MacLean, however, emphasised the old industries that had built Prince Edward Island: the fisheries and the family farm. While Campbell might want to spend Ottawa’s money on economic diversification, MacLean wanted more self-sufficiency and autonomy for PEI — and for Islanders themselves.

Despite Campbell’s modernity, politics could still be old-fashioned in PEI. The Canadian Press reported “a predictable element of old-style politics [that emerged after the writ drop] — a stream of highway repair trucks.”

Widely considered a bitter campaign, the most competitive since Campbell had come to power, the PCs emphasised the team around MacLean, while the Liberals put the focus on the premier.

The Liberals had many promises in their platform, denounced as a “shopping list” by MacLean, while the PCs spoke broadly about values and objectives but kept their promises unspecific and a platform was never even released.

That unorthodox approach contrasted with that of the Liberals.

“The party has also taken some hard knocks over the slickness of its advertising,” Dorrell wrote. “The campaign, conducted by an out-of-province firm, features a photograph of Mr. Campbell in which the bags and worry-lines around his eyes have been air-brushed away, leaving the unfortunate impression that he has never known a hard day at the office.”

The results were extremely close. The Liberals dropped nine seats to just 17, with the PCs picking up nine to finish with 15. The Liberals took just under 51% of the vote while the PCs took just over 48%. Only 50 votes separated the Liberals’ Ralph Johnstone from Flora Bagnall of the PCs in 1st Queens. Without those votes, the two parties would have ended in a tie.

The NDP, which ran a far smaller slate of candidates than it did in 1974, took less than 1% of ballots cast.

The Liberals lost seats across the island, but primarily in and around Charlottetown. Their block of seats in Prince County at the western extremity of PEI kept them in office.

Islanders were nearly evenly split — and in some cases they literally were. At the time, Islanders elected two members to the legislature for every seat, one a “councillor” and the other an “assemblyman”. In five of PEI’s 16 districts, voters elected a Liberal for one of those titles and a Tory for the other.

“It was a squeaker, all right,” Campbell admitted on election night.

For the PCs, it looked like the Liberal government was nearly done. MacLean commented that it was “just a matter of whether it’s going in one sweep or in installments.”

After 12 years as premier and facing a divided legislature — the Liberal speaker reduced the party’s majority to one — Campbell decided to resign later that year. It put the legislature in an even more unstable situation. Bennett Campbell, his successor as premier but no relation, called an election in early 1979 to settle the impasse. Islanders indeed broke the tie, and Angus MacLean became premier.

1993 Prince Edward Island Liberal leadership

A coronation for Catherine Callbeck

January 23, 1993

The 1980s and early 1990s were dominated by constitutional debates — Quebec’s referendum in 1980, the negotiations over the repatriation of the constitution in 1981, the Meech Lake Accord of 1987 and the Charlottetown referendum in 1992. It elevated provincial premiers to the national stage. While that might not have necessarily made them household names, even the premiers of Canada’s smallest provinces were national figures.

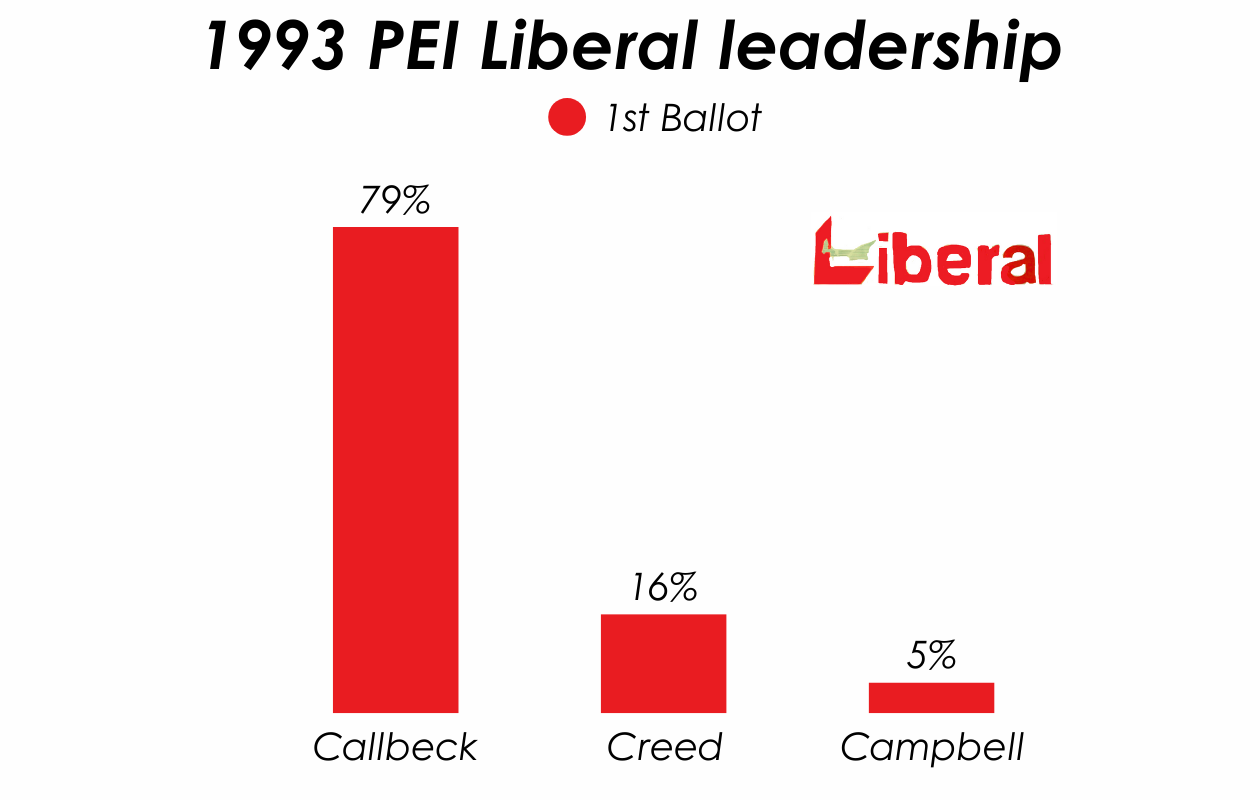

Joe Ghiz was one of them, having become premier of Prince Edward Island in 1986. His Liberals dominated the province, winning all but two seats in his 1989 re-election campaign and still being very popular in the polls as the next election approached. But Ghiz decided that was enough, and announced his resignation in October 1992.

A handful of provincial cabinet ministers were touted as serious contenders, but in the end there was only one: Catherine Callbeck. First elected as an MLA in 1974, after which she served in cabinet for one term before leaving politics for a time, Callbeck had been the Liberal MP for Malpeque since 1988. She was the first to enter the leadership contest and resigned her federal seat, starting the campaign with the support of half of PEI’s cabinet ministers and most of the Liberal caucus. Her show of force dissuaded others from throwing their hats into the ring, something Callbeck didn’t mind.

"If no one else chooses to throw their hat in,” she said, “it could make the transfer smoother because leadership contests can be divisive.”

As the deadline for entering the race approached, it seemed like the PEI Liberals were heading for an acclamation. But on the very last day, two men stepped up to challenge Callbeck.

One was Bill Campbell, a social activist and federal civil servant somewhat well-known in Charlottetown.

The other was a complete unknown. Larry Creed, in his late 20s, was an unemployed construction worker and called himself the “beans and bologna candidate”. He admitted he entered the race simply because it was heading for a coronation.

Neither Creed nor Campbell had any political experience and Callbeck was the heavy favourite. She ran a largely promise-free campaign (wanting to save those for the upcoming election), but there was some disagreement over the Confederation Bridge — Callbeck wanted it to go ahead as planned, while Creed wanted a plebiscite on it.

More than 1,500 delegates (a big number in a province of around 130,000 people) attended the convention in Charlottetown, but it was a “low-key convention with only token demonstrations and little sign-waving on a convention-room floor so packed with chairs that there wasn't much room for it anyway”, according to the Ottawa Citizen’s correspondent.

“While Campbell emotionally promised full employment in 10 years and Creed choked up when he mentioned his parents, Callbeck delivered a cool, straightlaced speech reflecting her meticulous personality and middle-of-the-road Liberalism.”

The result was a landslide victory — as expected.

Callbeck took 79% of the vote on the first ballot, easily beating both Creed and Campbell, who took 16% and 5% of delegates’ votes, respectively.

Callbeck had just become the premier of Prince Edward Island — and only the second woman to become premier in Canada’s history, having been beaten to the punch by British Columbia’s Rita Johnston by little more than a year.

She wasn’t intimidated at the prospect of being a woman in a male-dominated field.

"When I took my Bachelor of Commerce at Mount Allison,” she said, “I was the only woman in the class. When I taught at Saint John Institute of Technology, I was the only woman on the business administration staff. When I served in cabinet in Prince Edward Island I was the only woman. When I was in business, I dealt mainly with men."

Without a seat in the legislature, Callbeck didn’t waste any time before calling an election, setting a date for March. In the 1993 PEI election, she rode a wave of popularity (and a tide going against anything Tory blue at the time) to win 31 of 32 seats — another landslide victory, making her the first Canadian woman to lead a political party to electoral success.

1993 Prince Edward Island election

Prince Edward Island makes history

March 29, 1993

For Catherine Callbeck and the Liberals of Prince Edward Island, 1993 held little suspense.

After Joe Ghiz announced his resignation as premier, a job he had held since 1986, it quickly became apparent that Callbeck, the Liberal MP for Malpeque and former provincial cabinet minister, would be his successor. Some 1,500 delegates confirmed this in January 1993 when they overwhelmingly gave their support to Callbeck over her two little-known opponents.

A provincial election was expected shortly after Callbeck was sworn in as premier — and it set up a campaign unlike any other seen in Canada before, as two women leading parties of government faced off against each other.

The PEI Progressive Conservatives, who had been thrashed by Ghiz’s Liberals in 1989, had chosen Pat Mella as their leader a year later. A school teacher, Mella energetically critiqued the Liberal government from outside the legislature.

That’s because there weren’t many seats reserved for Tories in Charlottetown. In the last election, the Liberals had won 30 of 32. And even one of those two PC MLAs had been persuaded to resign in order to accept a government appointment from the Liberals. The other MLA, perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, decided not to re-offer.

That meant Mella would be leading a cast of 32 candidates without a single incumbent among them.

“I think it’s time for a change,” Mella said, “and you might as well mean it literally.”

Politically, things looked good for the Liberals. But Callbeck had her own challenges to face as premier of a province with 18% unemployment and prospects of more job losses on the horizon.

One of those fears was that Jean Chrétien’s Liberals, widely expected to defeat the PCs in a federal election later that year, would put a stop to the building of a tax facility in Summerside to process the GST. Chrétien had pledged he would scrap the GST, which would put hundreds of jobs in Summerside in danger.

In the end, Islanders needn’t have worried.

Playing it safe, Callbeck ran a campaign of “splashy advertisements, bland speeches and personal contact with thousands of voters in muddy farmyards and chilly church basements,” according to The Globe and Mail’s Kevin Cox. Callbeck avoided controversy and detailed commitments whereover possible.

Mella, by comparison, was a lively speaker and sharp critic, and her detailed platform included many promises to Islanders, including attention-grabbing ones like ending political patronage and funding kindergarten. But she wasn’t able to move the dial much in her favour, and having to apologize for some radio ads that went after Callbeck personally — attack ads were just not how things were done in PEI — did not help matters.

In a climate of insecurity and uncertainty about the province’s economic future, Islanders opted for the status quo — and nearly awarded the Liberals a sweep.

The Liberals captured 31 seats, a gain of one from the previous election. The party captured both of the seats vacated by the PC MLAs but left one on the table: Pat Mella’s.

It was a disappointing result for the PCs, who had hoped to make a breakthrough. But Mella was able to get herself a seat in the legislature and increase her party’s share of the vote by four points to 39.5%. The Liberals dropped nearly six points to 55.1%, but it didn’t matter much. Callbeck had coupled her leadership landslide in January with an electoral landslide little more than two months later.

Her victory didn’t make her Canada’s first female provincial premier, as Rita Johnston beat her to that title in 1991 in British Columbia. But Johnston and her Social Credit Party went down to defeat later that year. Avoiding that fate made Callbeck the first woman to become premier with an electoral mandate of her own — not that Callbeck thought much about it.

“I can honestly say I don’t feel that type of pressure,” she said. “I’m the sort of person that I take on a challenge and I do the best I can, that’s what I’m going to do as premier of Prince Edward Island.”

2003 Prince Edward Island Liberal leadership

A second Ghiz for the Liberals

April 5, 2003

The 2000 provincial election in Prince Edward Island was one the PEI Liberals wanted to forget.

Against Pat Binns’s incumbent Progressive Conservative government, Wayne Carew nearly led the party to complete destruction. The Liberals were reduced to just a single seat (and that won by just 157 votes) and 34% support. At the time, that represented the worst performance for the Liberals in the party’s long history. (The party reached a new low this past Monday.)

Carew held on as leader for a few months, but by the fall of 2000 he decided it was time to step down.

"It will always be something that you wish you could have another crack at," he said. Ron MacKinley, the lone Liberal survivor from 2000, took over as interim leader.

There wasn’t much of a rush to fill that job in a province dominated by Binns and the PCs. Not until February 2003, just a few weeks before the nomination deadline, did two candidates come forward.

Alan Buchanan was the first. An MLA for 4th Queens from 1989 to 1996, Buchanan had served as a cabinet minister in the Joe Ghiz and Catherine Callbeck governments, taking on important portfolios like health and justice. Since leaving politics ahead of the 1996 campaign that brought the PCs to power, Buchanan had been working in the private sector. He launched his leadership campaign in his hometown of Belfast in front of 250 supporters.

A few days later, Robert Ghiz joined the fray.

A familiar name in Prince Edward Island as the son of Joe Ghiz, premier from 1986 to 1993 (he passed away from cancer in 1996), Robert Ghiz was just 29 years old. While the family name was well-known among Islanders, his was also a well-known face in Liberal circles, as Robert Ghiz served as Atlantic advisor to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien.

"We need a resurgence of energy that has been the backbone of our party,” he told the 275 or so supporters gathered for his campaign launch in Charlottetown. “We need a leader who wants to work hard, a leader who will bring about dramatic change in this organization — a change in attitude, a change in mind set."

Ghiz, however, was not banking his strategy on nostalgia for the years of his father, who led the Liberals to big victories in 1986 and 1989.

"I'm not my father,” he said. “I just hope I can learn from some of the good things he did on PEI."

The convention at the Charlottetown Civic Centre was very well-attended, as nearly 4,000 Liberal party members would cast a ballot.

"I didn't know there were this many Liberals left on P.E.I.," one delegate joked to the CBC.

While Ghiz pitched the message of renewal, Buchanan leaned into his experience. During his convention speech, he argued that "I am ready to lead this party. I have earned my stripes and my apprenticeship is over." But decisions he had made when in government, particularly a pay cut for public sector workers, were still haunting him.

With 3,979 ballots cast, Ghiz emerged as the favourite — but only just. He earned the support of 2,065 delegates, giving him 52% of the vote. Buchanan was only 161 votes behind with 1,904, or 48%.

"The Liberal Party is ready for change,” Ghiz said in his speech before the ballots were cast. “The province is ready for change, the Tory era is ending and I am here to offer this party a fresh start.”

"We need to learn from our past, live in the present and build now for the future. Today is the start of a new page in the history of our party."

He was right about that, but that new page wouldn’t be turned just yet.

In the 2003 election called a few months later, Ghiz would improve the Liberals’ standing, win himself and three other Liberals a seat in the legislature and increase the party’s vote share by eight percentage points. Unlike Carew, he would get another crack at the premiership. But he’d have to wait four more years before occupying the same office that his father once did.

2003 Prince Edward Island election

A hat trick for Pat Binns

September 29, 2003

After two consecutive majority governments for the P.E.I. Progressive Conservatives, premier Pat Binns decided to go for something no Tory had managed before in P.E.I. since the 19th century: three wins in a row.

The omens for Binns and the PCs looked good in mid-2003. The last election had only been three years earlier, but unemployment in Prince Edward Island was low (by P.E.I. standards) at 11% and the number of jobs had increased significantly since the PCs had come to office in 1996. Polls put satisfaction with the Binns government around 80% and, just to leave nothing to chance, the PCs had spent the months before the election call announcing new reductions in fees and taxes, such as the capping of auto-insurance rates. That had been a thorny issue which hurt other PC premiers in the Maritimes, and Binns wasn’t going to take the risk.

A bean farmer and one-term PC MP during the Brian Mulroney years, the 54-year-old Binns announced the expected election at his own nomination meeting. His was the last of the 27 PC nominations that needed to be lined up.

Against the PCs, the Liberals had a fresh face in their new leader — though not an unfamiliar name. In April 2003, the party had chosen the 29-year-old Robert Ghiz, son of former premier Joe Ghiz, who had governed from 1986 to 1992 and had passed away in 1996. Robert Ghiz won by a margin of 161 votes over former cabinet minister Alan Buchanan in a contest in which 4,000 Islanders cast a ballot.

Despite the interest, the prize at the time was not particularly glittering.

The Liberals had been out of power for seven years and had been shellacked in the last election when they had been reduced to just a single seat in the 27-seat Legislative Assembly. Only 157 votes in that one riding had prevented a clean sweep of the island by the PCs.

But P.E.I. had only ever known two parties of government — the Liberals and the Tories. If Ghiz wasn’t the favourite to win the upcoming election, he would eventually get a good shot at becoming premier.

While young, Ghiz boosted the party’s fortunes. His father had been a popular premier, though his son rarely spoke of his father on the stump as he wanted to steer his own course. He gave the moribund Liberals new energy and criticized the government for increased electricity rates, one of its few vulnerabilities. He also put the premier on the defensive during the leaders debate.

The Liberals started the campaign about 20 points behind the PCs in the polls, but by election day the race was looking closer. No one, though, doubted that Binns would prevail in what had been widely seen as a low-key, dull election without any major controversy or decisive issue.

On voting day, the damage from Hurricane Juan couldn’t keep Islanders from casting a ballot, as turnout still managed 83% despite nearly half of households losing power. Even Binns had to watch the results on a small TV powered by a generator.

Those results gave the PCs its third consecutive majority government with 23 seats, a loss of only three since the previous election. The PCs still managed to win a majority of ballots cast despite dropping nearly four points.

Ghiz and the Liberals put up a decent fight, gaining three seats (two of them in Charlottetown, including the district in which Ghiz was running) and increasing their vote share by eight percentage points, ending with just under 43%.

The New Democrats, under rookie leader Gary Robichaud, managed just 3.1% of the vote. The party had failed to run a full slate and finished no better than third in any riding, barely clearing double-digits in just one district.

For Binns and the PCs, the gamble of an early election had paid off nicely. On election night, Binns joked that “sometimes it's called P.E.I., sometimes it's P.E. Island. But tonight I want to call it P.C. Island."

I guess you had to be there.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Prince Edward Island and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

Just a note after reading your capsule about the 1978 PEI election and the close race in 1st Queens. The losing Tory candidate, described here as Flora, used her middle name and was known as Leone Bagnall. She went on to win a rematch in the next election and many elections after that. She was briefly interim Tory leader after Jim Lee's defeat in the late 80s.

Enjoying catching up with older capsules when you cross reference them in current posts.