#EveryElectionProject: Nova Scotia

Capsules on Nova Scotia's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Nova Scotia.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1867 Nova Scotia election

Nova Scotia votes against the Union

September 18, 1867

A few months after the establishment of Canada, voters in one province showed that, had it been put to a referendum, they would have soundly rejected the new country.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were at the centre of opposition to Confederation. The two smaller British colonies were unsure about joining the two bigger ones — Ontario and Quebec, then known as Canada West and Canada East. New Brunswick settled matters in an election in 1866 and Nova Scotia was brought into the union through the work of Charles Tupper, then leader of the pre-Confederation government.

But despite getting Confederation passed through Nova Scotia’s legislature, opposition was still strong. Tupper hoped to make the jump to national politics and handed over the administration of the new province to Hiram Blanchard, who would lead pro-Confederation forces (largely made-up of Conservatives) into the provincial election campaign against the Anti-Confederates (largely made up of Liberals, or Reformers, as they were also called at the time).

The federal and provincial elections took place in Nova Scotia on the same day on September 18, 1867. The provincial and federal campaigns were fought over the same issue: Nova Scotia’s place in Confederation.

The Anti-Confederates were led by the firebrand Joseph Howe, who had campaigned against Nova Scotia’s joining Canada and had travelled to the United Kingdom to make the case. When he was away, leadership of local opposition to Confederation fell to William Annand, who called the union “hateful and obnoxious”.

Tupper ran for the House of Commons in Cumberland, perhaps sensing that he would be unlikely to win a provincial campaign. Annand put his name on the ballot against him. Howe, not wanting to risk a defeat to Tupper, ran in Hants — again for federal office. But the campaign was a duel between Tupper and Howe, and the two met each other on the campaign trail throughout the summer.

It didn’t matter much that Tupper, Howe and Annand were all fighting for federal office — it was impossible to separate the national debate from the local provincial campaign. In fact, when it was all over, the next premier in Halifax would prove to have run for a seat in Ottawa.

The fiercely anti-Confederation Morning Chronicle set the stakes in stark terms on election day, and predicted victory:

“To-day the people of Nova Scotia will decide whether they are or are not, as they have been represented, too ignorant and prejudiced to govern themselves … Looking forward to this day we have always maintained that it would witness an overwhelming defeat of the slanderers of the people, and now that it has arrived we feel more confident than ever … Once again we fearlessly repeat that a victory such as no party ever gained will be ours to-day. But we must work to render it as brilliant as possible.”

(Note, there is some inconsistency in Elections Nova Scotia’s own sources regarding vote totals. But a 60-40 split seems reasonable. The Anti-Confederates also won a few seats by acclamation.)

As was the case federally, where the Anti-Confederates swept all but one seat (Tupper’s), the provincial campaign ended in a landslide victory for the Antis. They won 36 of 38 seats. Only in Cumberland, where Henry Gesner Pineo rode Tupper’s federal coattails to win election, and in Inverness, where Hiram Blanchard squeaked in by 54 votes, did the Anti-Confederates fail to win every seat.

“Thank God,” wrote the Morning Chronicle on September 19, “Nova Scotia has shown herself worthy of being a free country.”

Annand lost his match-up with Tupper in Cumberland, but no matter. He was named to the Legislative Council (the provincial version of the Senate that was then in existence) and would be Nova Scotia’s premier once Blanchard’s government was defeated in the legislature.

The people of Nova Scotia had spoken — and they had voted against the Union. Howe once again took their arguments to London, but British politicians were uninterested. They had wanted to get British North America off their hands in the first place and didn’t want to take it back.

Howe would eventually give up and join John A. Macdonald’s government. Annand wouldn’t move on, however, and tried to see Howe defeated in the byelection following Howe’s appointment to cabinet. He was unsuccessful in seeing his old ally beaten, but his fight for “provincial rights” wasn’t over.

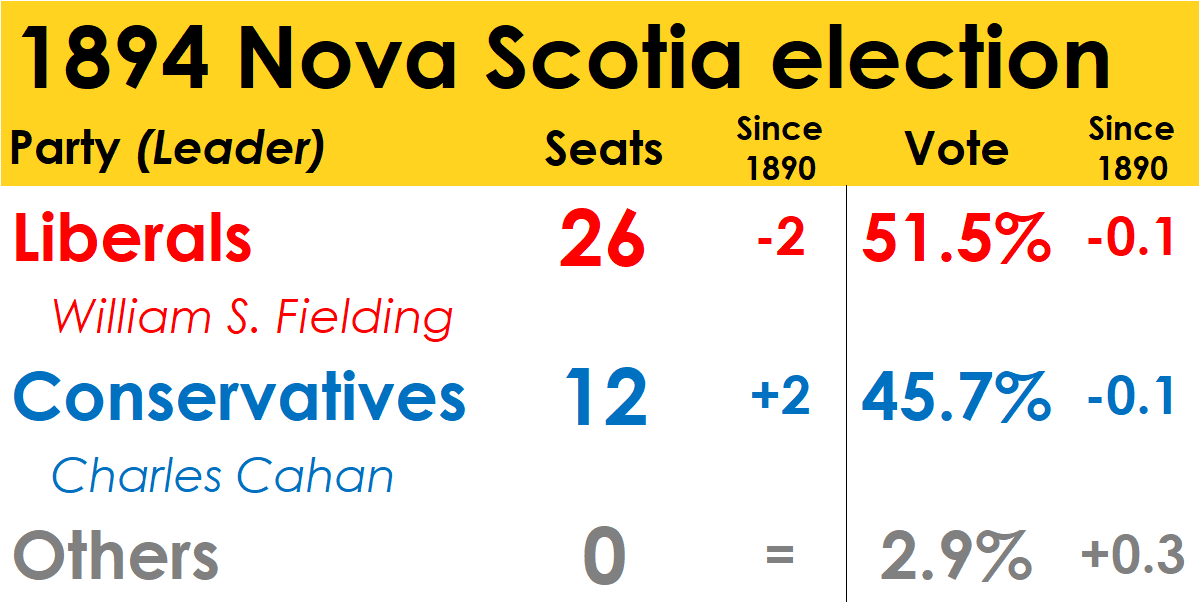

1894 Nova Scotia election

Fielding returned for the last time

March 8-15, 1894

Provincial and federal politics have never been completely separate — and in Nova Scotia in the 1880s and 1890s the links between the two could be decisive.

At the time, Canadian unity was not about Quebec or (the not-yet-existing) Alberta, but rather the province of Nova Scotia. It had never been entirely keen on joining Confederation and in the 1880s Nova Scotians indirectly voted to leave.

That happened under the leadership of William Stevens Fielding, who entered politics in 1882 and became premier in 1884. That job came with the responsibility of being the provincial treasurer, and Fielding dedicated himself to fixing Nova Scotia’s finances. The biggest problem he saw was the inadequate deal the province had with the Dominion government. Most of Nova Scotia’s revenues came via the federal subsidy — and it wasn’t enough.

In 1886, Fielding led his Liberals into an election campaign on the issue of secession and won a big majority. But the issue soon ran out of steam when Fielding couldn’t convince his fellow Maritime premiers to join a “Maritime Union”, and the British (who still had the final say) were even less enamoured with the idea. Losses suffered by the federal Liberals in Nova Scotia in the 1887 election definitively put secession on the back burner.

Fielding only mentioned it in passing in 1890, when he won another big majority government. By 1894, Fielding had reconciled himself with the rest of the country and became an active participant in federal politics, attending the 1893 National Liberal Convention and solidifying himself as the leader of Liberal forces, both provincial and Dominion, in Nova Scotia.

Instead of separation, Fielding looked at developing Nova Scotia’s industries and invested heavily in the development of the coal mines in Cape Breton — a move that would eventually give Nova Scotia the revenues it was lacking from Ottawa.

The campaign in 1894 was dubbed “the most bitter ever held in this Province” by the correspondent of the Globe, claiming that while the parties had “signed a written agreement not to supply liquor or money … it has been discovered that during the last 48 hours immense quantities of liquor were sent into the country districts and money was freely used both there and in the city.”

Against Fielding was Charles Cahan, who had taken over as leader of the Conservative (or Liberal-Conservative, as it was interchangeably called at the time) opposition after his predecessor, William MacKay, lost the 1890 election and his own seat.

Cahan and the Conservatives tried to tie provincial and federal politics together during the campaign. In 1891, Fielding and the Liberals had campaigned with Wilfrid Laurier against John A. Macdonald’s National Policy of tariffs, a policy that was popular in parts of Nova Scotia, particularly in Cape Breton where freer trade would have a negative impact on the coal trade. In that federal election, the Conservatives under Macdonald won three-quarters of Nova Scotia’s seats.

But in 1894, John A. Macdonald was dead and the Conservatives couldn’t turn the tide against Fielding.

The Liberals were re-elected, winning 26 seats and losing only two compared to the 1890 election. The Conservatives finished with 12 seats, up two, while each party’s share of the province wide vote was virtually identical to what it had been in 1890: 51.5% for the Liberals and 45.7% for the Conservatives.

“The Liberals of Halifax held a mass meeting in the Lyceum to-night,” reported the Globe, “from the stage of which the returns were announced as received by telegraph operators. The building was packed, hundreds blocking the streets leading to the Lyceum and being unable to obtain admission.”

The Liberals gained a few seats from the Conservatives, including in Cumberland, Guysborough and in Shelburne, where Cahan went down to defeat. MacKay, however, managed to get back into the Legislative Assembly and would replace Cahan as Conservative leader once again.

Liberal losses, though, included two in Cape Breton and two in Inverness — a sign of the continued popularity of the National Policy and the lack of inroads Fielding was able to make despite his investments in the coal industry.

Fielding would make the final break with provincial politics and his opposition to Confederation in 1896, when he joined several other Liberal premiers in making the jump to federal politics as a member of Wilfrid Laurier’s first cabinet. But the Liberal dynasty would long outlast him — the Conservatives would remain on the opposition benches in Nova Scotia for another three decades.

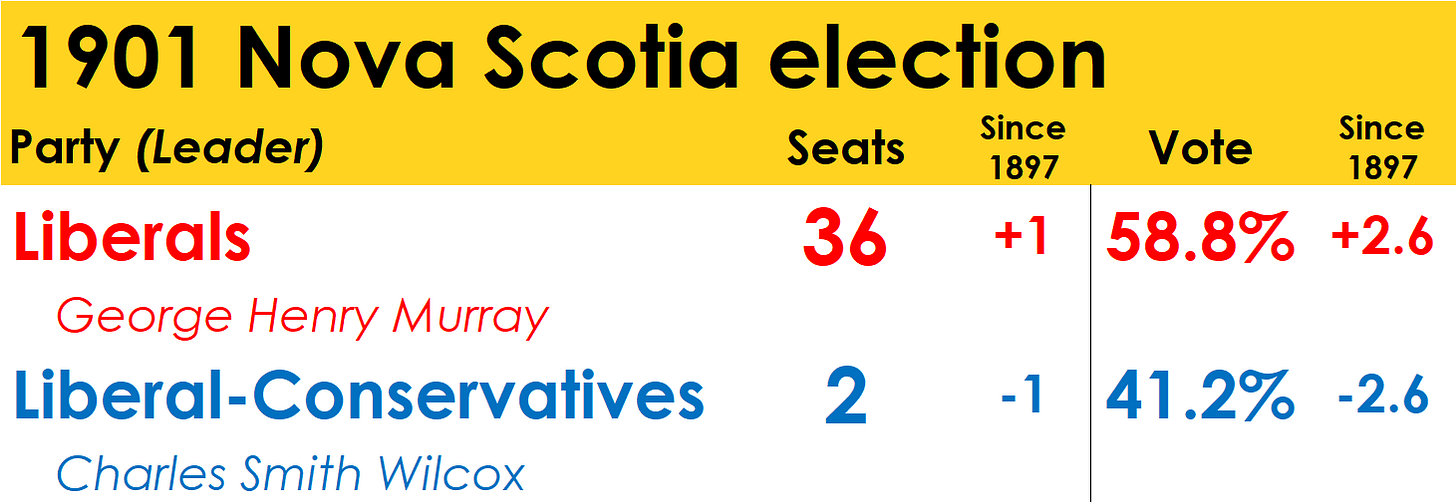

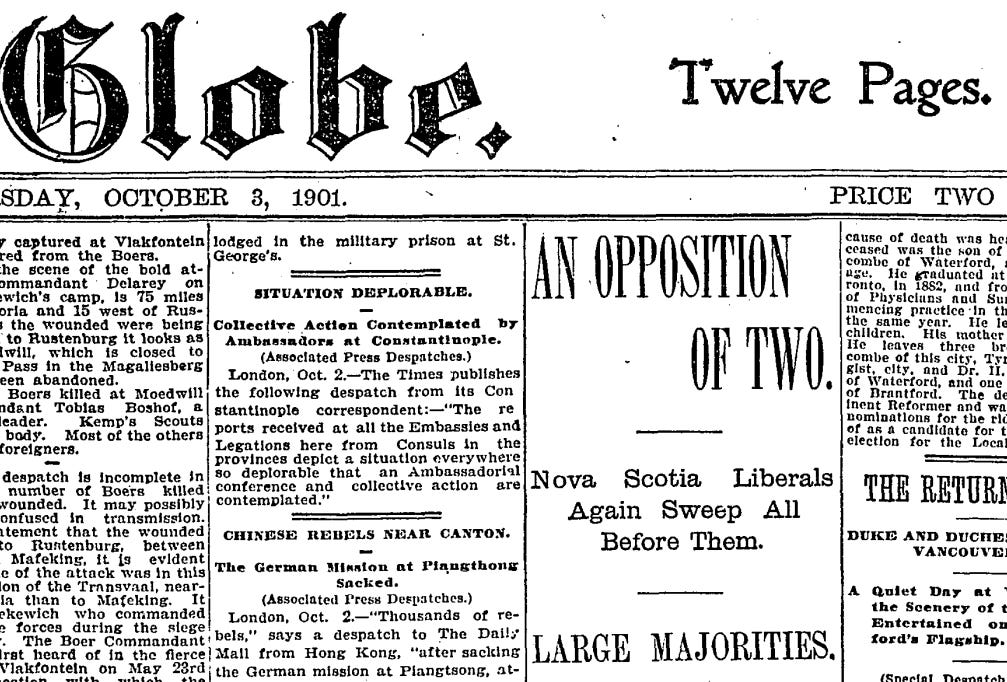

1901 Nova Scotia election

An Opposition of Two

October 2, 1901

When George Henry Murray called an election in Nova Scotia for October 2, 1901, he had every right to expect that he’d win again. His Liberals had been in office for nearly 20 years. He himself had won a solid majority victory in 1897, shortly after he replaced W.S. Fielding as premier of the province, by winning 35 of 38 seats.

The Liberals under Wilfrid Laurier had ousted the Conservatives from national office in 1896 and the benefits of the Liberal connection between Halifax and Ottawa were clear. Fielding still held a great degree of sway in Nova Scotia after joining Laurier’s new cabinet, and the friendly atmosphere helped liberate $617,000 from Dominion coffers to finance the construction of new branch railways in the province, money that the former Conservative government had refused to share.

Murray, who would prove to be one of the most electorally successful party leaders in Canadian history, was not a particularly dynamic or skilled politician. But he inherited a strong party organization from Fielding and he kept his government rather clean — at least by the standards of the time. Murray was seen as an honest, friendly and cautious leader who didn’t rock the boat or hesitate to speak to the man in the street.

Against Murray in the 1901 election were the Conservatives (or Liberal-Conservatives, as they were also known) under Charles Smith Wilcox, who unexpectedly found himself leader of the party after the Conservatives were reduced to just three seats in the legislature in 1897. But he grew into the job, emerging as a strident critic of the Liberals on a few key files. When he died in 1909, he was described as “courteous in debate, considerate of the opinions of others and moderate in the presentation of his views.”

Against the juggernaut Liberals, Wilcox and the Conservatives would try their best. At a convention in July ahead of the October election, the Conservatives charged the Liberals “with making use of money, patronage and other corrupting influences to hold themselves in power” and questioned their management of the roads, the railways and the public finances of Nova Scotia. They also got some help from Robert Borden, leader of the national Conservative Party, who participated at the nominating convention in Halifax and campaigned for the Wilcox Conservatives during the election.

The Liberals got some help from Fielding, of course, but they had an easy case to make. It was their party that got the railway money from Ottawa. It was their party that had doubled the government’s revenues since 1882 and had made it possible for Nova Scotia to invest in things like infrastructure and education. Their policies had “been intelligent and progressive, and well adapted to the development of the great resources of the Province”, according to Murray.

The Conservatives tried to make the case for change — a tough sell in a province that would prove to be only halfway through a 43-year span of Liberal government. They reminded Nova Scotians that Murray had argued that no government should be kept in power for too long when he was campaigning against the federal Conservatives in 1896. Surely the same logic should apply to the Liberals’ long stint in office in Nova Scotia.

Voters didn’t buy it. The result was a lopsided victory for Murray’s Liberals. The party captured 36 seats, leaving just two for the Conservatives: one in Pictou and one in Cumberland. The Liberals swept everything else, including Hants where Wilcox went down to defeat.

In trying to explain the landslide Liberal win, the Liberal-friendly Globe ventured “it would appear that the Government had a record which could not be seriously attacked, and that the Opposition, while it presented an elaborate programme to the electors, was unable to concentrate public attention upon any one issue.”

The second of what would be Murray’s six consecutive majority victories did not bring the Liberal leader much happiness. He suffered a nervous breakdown after the election that was described as “gloominess, depression, want of confidence in himself.” He spent most of the next year’s legislative session in the United States for treatment, but he’d be back to his winning ways before long — though he’d never again repeat his feat of limiting his opposition to just two.

1920 Nova Scotia election

A Nova Scotia dynasty rolls on

July 27, 1920

Remember when Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives were first elected in 1984? Now, imagine that government was still in power today — and about to be re-elected.

That’s what the situation was like in Nova Scotia in 1920 when George H. Murray sent the province to the polls.

His Nova Scotia Liberals had been in power since 1882 and Murray himself had been in office since 1896. With that uninterrupted record of winning, perhaps it is not surprising that few thought Murray’s Liberals were in any danger in 1920.

But the 1920s were a topsy-turvy time in Canadian politics. The First World War had shattered the old systems that kept different classes in their places and only two parties anywhere close to government.

Farmers were unhappy with the status quo and starting their own parties throughout the country. The United Farmers had already taken power in Ontario. It would not be the only place where the two old parties were shoved aside.

Labour groups were becoming restless. The Winnipeg General Strike had taken place only the year before. The Independent Labour Party was starting to make inroads. In Nova Scotia, the coal miners in Cape Breton wanted change.

And, for the first time, women were voting.

It made for an unpredictable time in Canadian politics. Could that tumult upset the apple cart in staid Liberal Nova Scotia?

Murray didn’t think so, and on June 29, 1920 he called an election that would be held on July 27.

The premier made the case to voters that Nova Scotia was in pretty good shape. The legislature was running well and the government had put into place measures to ease the return of Great War veterans into civilian life. Highways were being built, the Nova Scotia Power Commission had been created and benefits had been increased for widows and children.

Trying to prevent farmers from drifting away from the Liberal Party, Murray claimed “it can be said, without possibility of contradiction, that the farmers of Nova Scotia have never made any request of the Government which has not received a generous response. Every effort has been made to encourage an increased production.”

The Conservatives under W.L. Hall didn’t buy it. Their support largely came in rural areas of the province, and Hall charged that the Liberals had “deliberately set a date in the busiest season of the farmers and fishermen, hoping to prevent their active participation in the campaign.”

If the farmers stayed home, he thought, the Liberals would be re-elected.

Hall said that the Liberals hadn’t done as much as they could have during their 38 years of government and that theirs wasn’t nearly the “progressive” government that Murray claimed to run.

The Liberals were also under attack from Labour, who said their priority was to provide the “proper shelter, food and clothing” for people so that “workers should be emancipated from the position of serfdom they occupy at present.” Labour was also for more direct democracy through referendums and proportional representation.

The party had its best chances in Cape Breton, where workers were disappointed that the Murray government hadn’t enacted an eight-hour day.

As was the case in other parts of Canada, the United Farmers and the Independent Labour Party co-operated in the Nova Scotia campaign, strategically running candidates where they would not get in each other’s way.

But with all these voices calling for the end of Liberal rule, the campaign was still, in the words of The Globe, “the quietest Provincial election campaign in the history of Nova Scotia” and, according to the 1920 edition of The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, “there were no scandals to give the contest a flavour which had been too common in past Canadian elections.”

Despite a drop in support, the result was another big win for Murray. The Liberals won 29 seats, only one fewer than in the 1916 provincial election. The Liberals defeated Conservative candidates in Kings and Queens counties and swept all five of the Halifax seats. In Cumberland and Cape Breton, however, the rise of Labour and the Farmers cost the Liberals.

The Farmers would win the second-most seats in the election with six. Their strength was concentrated in the neighbouring counties of Cumberland, Colchester and Hants. They also won a seat in Antigonish.

Labour won a seat in Cumberland, too, while four of its five seats came in Cape Breton around Sydney.

Combined, the Farmers and Labour won about 32% of the vote, more than the Conservatives whose support collapsed by nearly half to just 23%. The party held on to only three seats: two in Richmond and one in Yarmouth.

Hall, who went down to personal defeat in his riding, blamed the party’s loss on “the brief period at our disposal for organization, and the remarkably short notice we had that an election was pending.”

The Liberal-friendly Globe saw the result as a warning to the Conservatives in Ottawa, saying “it is another notice to Mr. Meighen and his office-holding Administration of the fate which awaits them when the electors of the Dominion come to the polls.”

In the end, The Globe wasn’t wrong. The rise of Labour and the United Farmers in Nova Scotia came largely at the expense of the Conservatives. The disintegration of the two-party system that began after the First World War would fell Arthur Meighen’s Conservatives in the 1921 federal election. When that vote was over, the Conservatives would find themselves in third — and shut out in Nova Scotia.

1933 Nova Scotia election

August 22, 1933

This instalment of the #EveryElectionProject was not from The Weekly Writ, but a longer form article. You can access it below:

1956 Nova Scotia election

“In with the new” in Nova Scotia

October 30, 1956

By 1956, the Nova Scotia Liberals had governed the province for eight of the previous 74 years and had been in power for 23 years straight, nearly all of that under Premier Angus L. Macdonald.

Known as Angus L., the premier had dominated Nova Scotia politics ever since he had ousted the Conservatives from office in the midst of the Depression. Not even a brief stint in Mackenzie King’s cabinet during the Second World War could keep him away from provincial politics long — he resigned as premier to take the post and took the premier’s chair back once the war was won.

But Macdonald died in 1954, leaving the Nova Scotia Liberals without their iconic father figure at the helm. By then, his government was also starting to show its age, with many of his best ministers long retired.

The party didn’t help matters when Henry Hicks won a divisive leadership race that pitted Protestants and Catholics against each other. Harold Connolly, an Irish Catholic MLA, couldn’t grow his support from one ballot to the next as non-Catholic members went elsewhere. They finally settled on Hicks, but Connolly and Catholic Liberals couldn’t be reconciled with the party.

The split added to the difficulties of the Liberals’ organization heading into the 1956 election campaign. The party was still formidable, but the machinery had also atrophied after so many years of easy victories.

The last few, however, had been a bit tougher than in the past. The Progressive Conservatives, entirely shutout of the legislature in the 1945 election, were progressively increasing their representation under Robert Stanfield. The scion of a wealthy Nova Scotia family, Stanfield could dedicate his time and ample resources to the PCs. Under him, the party won eight seats in 1949 and 13 in 1953. It was building up its strength and momentum.

Both Hicks and Stanfield were relatively young politicians for the time — just 41 and 42 years old, respectively. But this would be Stanfield’s third campaign as party leader. Hicks was the rookie, and going into it he said he had “moderate confidence” that he’d win.

Though the province was doing well, there were questions whether it was falling behind the rest of the country as Canada’s post-war economy expanded. There were concerns that Nova Scotia wasn’t even leading the Maritime provinces anymore and had fallen behind New Brunswick — which had switched over to the Tories in 1952.

“Nova Scotia is walking backward into the future,” Stanfield argued, pitching greater economic development for the province.

But there wasn’t much separating the Liberals from the Tories in Nova Scotia. Both competed in promising to pave as many highways as possible, but the two parties were separated more by partisan, tribal loyalties than they were by policy. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation under Michael MacDonald differed more significantly, of course, but was only running a small slate of candidates, primarily in Nova Scotia’s industrial centres.

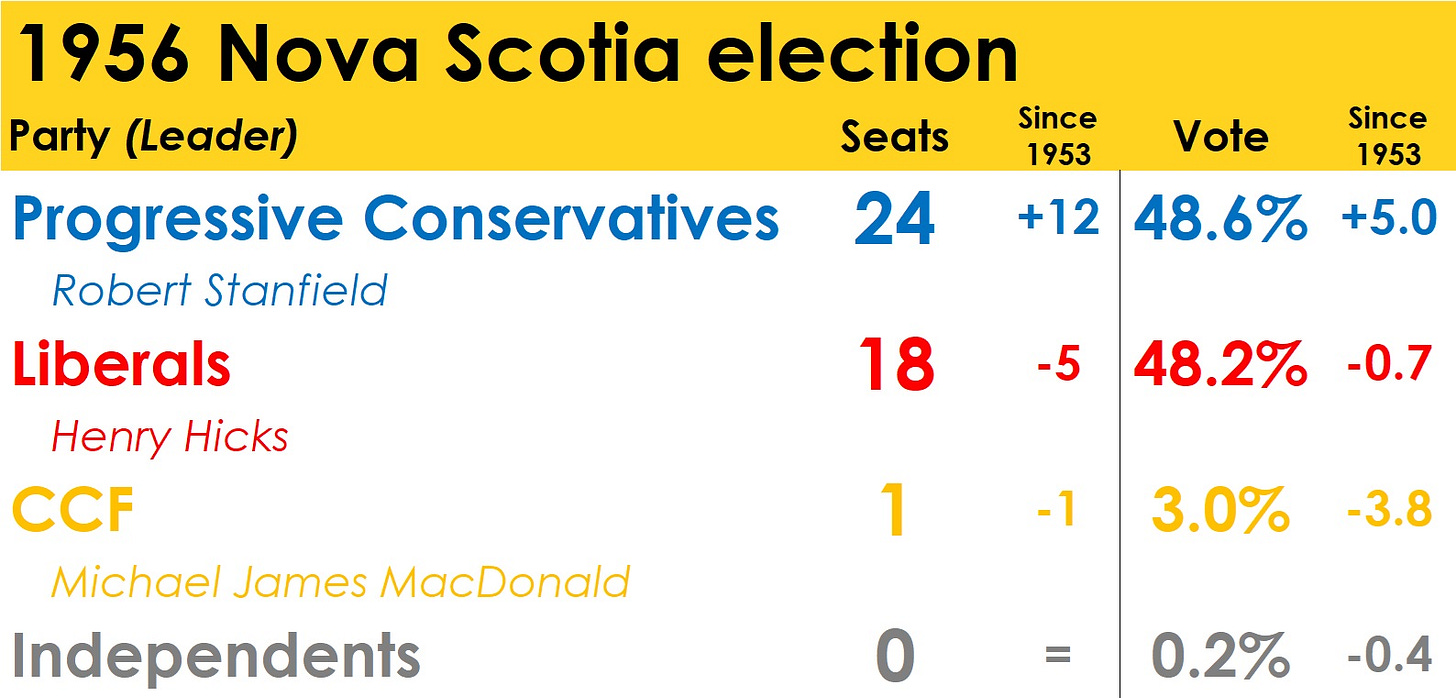

The election proved to be a close one, with the PCs taking 48.6% of the vote to the Liberals’ 48.2%. But Nova Scotians were ready for something new after nearly a quarter century of Liberal rule.

The seat results were not as tight, as the PCs won 24 to the Liberals’ 18. Hicks and the Liberals lost five seats compared to the last election, while the PCs picked up 12 — including some of the new seats that re-distribution had created.

Two regions in particular helped push the PCs to office. Citing “labour unrest” as the reason for their success, the PCs won five seats on Cape Breton, entirely around industrial Sydney. They also won all three seats in Pictou County. In 1953, the PCs had not won a single seat in either Pictou or Cape Breton.

The victory would prove to be the first of four for Stanfield, who increased his majority in each of the next three elections. His winning ways made him a national star within the Progressive Conservative Party and, when John Diefenbaker was forced out as national leader in 1967, the party faithful turned to Stanfield — just the kind of steady, serious and experienced leader the country seemed to be ready for after years of unstable minority rule in Ottawa.

But Stanfield was no longer new. And he didn’t shine as brightly as the Liberals’ star, Pierre Trudeau. He was new and interesting. Stanfield, by 1968, was not.

1971 Nova Scotia Progressive Conservative leadership

Nova Scotia Tories turn to the right

March 6, 1971

After a long period of stability, the Nova Scotia Progressive Conservatives experienced a few whirlwind years of change between 1967 and 1971.

Robert Stanfield took over the leadership of the Nova Scotia PC Party in 1948, only a few years after a disastrous 1945 campaign that saw it shutout of the legislature. Stanfield rebuilt the provincial party, growing its vote share and caucus until finally returning it to power in 1956. For the next decade, he continued the PCs’ upward trajectory until he decamped to Ottawa to take on the national PC Party. His replacement, G.I. Smith, took his place unopposed.

But then the PCs were dealt a narrow defeat in the October 1970 election, and two weeks later Smith suffered a heart attack while on vacation in Bermuda. Advised by his doctors to quit politics, Smith resigned the PC leadership. The search was on for another leader — and yet another new direction.

The names bandied about at the leadership contest’s outset didn’t materialize: former finance minister Tom McKeough, PC MP Pat Nowlan and well-known broadcaster and businessman Finlay MacDonald all decided not to run.

The three candidates who stepped into the vacuum were all under 40 and each proposed new directions for the party.

Gerald Doucet, the youngest of the three at 33 years old, was first elected as an MLA in Cape Breton in 1963. An Acadian, he served as minister of education and represented the progressive wing of the Progressive Conservative Party.

John Buchanan, the oldest at 39, represented a riding in Halifax that he won in 1967. After the dust settled following the 1970 campaign, he was the only PC MLA left standing in the city. Last serving as fisheries minister and, like Doucet, originally from Cape Breton, Buchanan was the first to announce his candidacy. He was seen to represent the conservative wing of the Progressive Conservative Party.

What both Doucet and Buchanan had against them, however, was their record as part of the Smith government that had just been defeated. That was not the case for Roland (Rollie) Thornhill, the 35-year-old mayor of Dartmouth. Originally from Newfoundland, Thornhill was seen as a potential contender from the start, in part because he didn’t carry any of the baggage of the previous government. He was also a compromise candidate, neither on the left or right wings of the party.

While the divisions between left and right might have created a dynamic campaign full of ideas and ideological clashes, instead it was a quiet, amicable affair needing “considerably more zest if it [was] to catch sizeable public attention”, according to Lyndon Watkins writing in the Globe and Mail.

Just under 3,000 delegates and observers attended the convention on March 5-6, 1971, which was addressed by Stanfield on the Friday before the voting.

Doucet’s speech to the delegates on Saturday didn’t land well. According to Watkins, “his speech contained more memorable phrases, but he delivered it in too forceful a manner. There was not sufficient modulation in this tone. ‘He sounded almost like Hitler to me,’ one delegate remarked.”

In contrast, Buchanan delivered a “low-key address”, pledging to make the Nova Scotia PCs “a people’s party to meet the challenge of the ‘70s.”

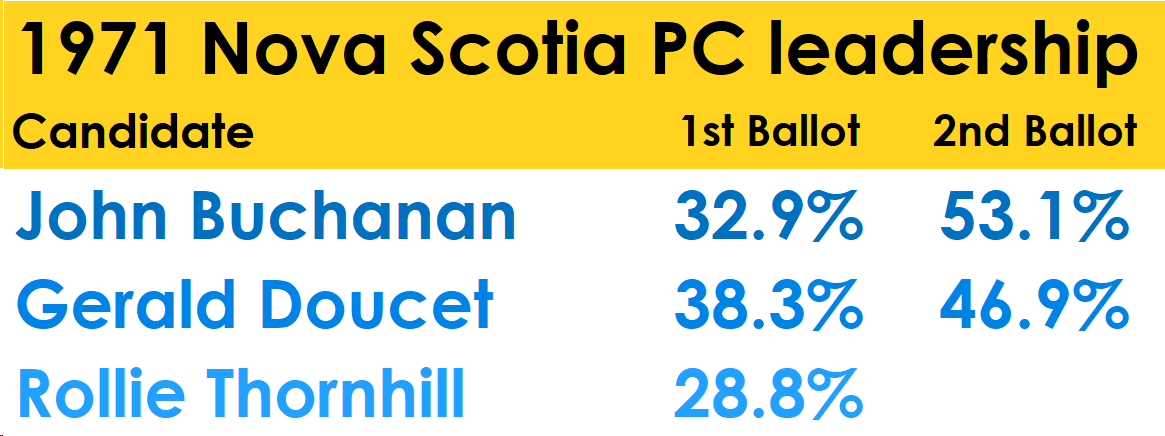

On the first ballot, Doucet emerged as the leader with 38% of the vote. But that proved not to be enough — Buchanan was second at 33% and Thornhill finished a strong third with 29%.

(There is a 10-vote discrepancy in reports from the Canadian Press and the Globe and Mail. I have used CP’s reported tally in the chart above.)

As soon as the results were announced, Thornhill walked over to Buchanan’s side of the hall. Most of his supporters followed him, voting for Buchanan over Doucet on the second ballot by a margin of nearly two-to-one.

Buchanan’s victory on that second ballot, with 53% to Doucet’s 47%, was interpreted as the members in the Halifax-Dartmouth area flexing their muscle. It also suggests that had Thornhill finished in second, he probably would have been able to roll-up Buchanan’s vote and beat Doucet.

In his victory speech, Buchanan promised to bring economic prosperity to Nova Scotia and so halt the flow of young people leaving the province.

“We must continue to have confidence in ourselves and in our capacity to shape our own destiny,” he said. “We must not become so dependent upon the central government that we become merely a colony of Ottawa, administered by the bureaucracy of Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Jean Marchand [one of Trudeau’s Quebec ministers].”

By the end of the decade, Buchanan would return the PCs to power, where they would remain until the early 1990s. When it was Buchanan’s turn to step aside, Thornhill (still relatively young 20 years later) ran for the leadership again. And, again, it was a near-run thing. Out of nearly 2,300 votes cast, Thornhill fell just 143 votes short of beating Donald Cameron and becoming premier.

1980 Nova Scotia NDP leadership

McDonough blazes trail in Nova Scotia

November 16, 1980

Never underestimate the drama of small parties.

In 1980, the Nova Scotia New Democrats qualified as one of those. Under Jeremy Akerman, the NDP had made progress by winning two seats in the 1970 Nova Scotia election and three seats in 1974, but were still only at four seats after the 1978 election.

That last result did not meet Akerman’s hopes, and after 12 years, limited success and disagreements with the party executive, Akerman decided to call it quits.

Three candidates emerged to replace him: Cape Breton North MLA Len Arsenault, Cape Breton Centre MLA Buddy MacEachern and two-time federal NDP candidate in Halifax, Alexa McDonough.

With Akerman out, what they were vying to take over was a party in turmoil.

The Nova Scotia NDP was a shaky coalition of the blue collar labour wing based in Cape Breton and the white collar professional (largely academic) wing of the party based in the rest of the province, particularly in Halifax.

Bitter over Akerman’s departure, maverick Cape Breton Nova MLA Paul MacEwen railed against his own party, claiming “Trostskyist elements” had taken over and that the NDP executive was “a bunch of ayatollahs”.

Sick of his outbursts, the party moved to expel him as a member of the NDP. But MacEwen was able to stay on as a member of the NDP caucus when Akerman and MacEachern voted to keep him in. Arsenault voted to boot him out.

Hoping to settle the matter at the leadership convention — which Akerman, now no longer a sitting MLA, refused to attend — the party passed a resolution saying that any caucus member would have to be a member of the party, effectively expelling MacEwen for good. This caused members of the United Mine Workers Union and the United Steel Workers to march out of the hall, followed by MacEachern.

Once tempers had mellowed, the party tried to put on a brave face of unity. In his speech to the convention, MacEachern said “I know the Liberals and Tories are watching the convention on television and rubbing their hands with glee, saying ‘They’re going to tear themselves apart.’ Well let me tell them, there has been no blood spilled here.”

MacEachern was on the losing side of the debate, as the party had decided it was done with MacEwen, who was threatening of forming his own NDP. But it wasn’t Arsenault who emerged as the vehicle of the anti-MacEwen, anti-Akerman vote. It was McDonough, the 36-year-old research assistant and former social worker.

When the ballots were counted, it wasn’t even close. McDonough finished with 237 votes from a party looking to move on. Arsenault was well behind with 42, just one more than MacEachern.

The Nova Scotia New Democrats had just made history. McDonough was the first female leader of a major political party in Canada (there had been others, like Thérèse Casgrain, who led minor parties before her).

It was such a novel concept, that some newspapers weren’t quite sure how to handle it. In the Southam News papers, the headline was “Woman to lead Nova Scotia NDP”, as if she was of another species.

Brian Butters, a correspondent for Southam News, betrayed the sexism of the time when he opened his article with “Nova Scotia's New Democratic Party has decided Alexa McDonough is more than just a pretty face.”

In McDonough’s first election as leader in 1981, her party would drop to just a single seat. But that seat was McDonough’s in Halifax, giving the NDP its first seat outside of Cape Breton — ever. (Paul MacEwen, the thorn in the side of the NDP, was re-elected as an Independent.) The party also captured 18% of the vote, the best it had ever done or would ever do until 1998. By then, McDonough had moved up in the world as leader of the federal New Democratic Party.

1991 Nova Scotia Progressive Conservative leadership

Cameron wins an uncoveted title

February 9, 1991

As the last decade of the 20th century dawned, the Nova Scotia Progressive Conservatives had little to look forward to. Under the leadership of John Buchanan since 1971, the PCs had come to power in 1978 and won re-election three more times. In the last of that series, however, the PCs were starting to falter — Buchanan limped over the finish line in 1988 with 28 seats in the 52-seat legislature.

A couple of years later, his government was drowning in scandal amid RCMP investigations and allegations of cronyism and corruption that touched both Buchanan and his cabinet. The party had just lost a byelection in Cape Breton badly and, wanting an out, Buchanan found one. In a case of game recognizing game, Brian Mulroney, himself polling in the low-teens, appointed Buchanan to the Senate.

The surprise move left the Nova Scotia PCs without much of an idea of where to turn next. Buchanan’s government had been a relatively quiet one with few cabinet ministers setting themselves apart from the pack.

But over the next few months, the list of candidates was formed. Tom McInnis, the MLA for Halifax Eastern Shore since 1978, was the early front runner. As the attorney general, McInnis had some profile and experience in other cabinet portfolios. Seen as a bit of a maverick, McInnis campaigned with the slogan “Reason to Believe” and, at the outset, he was the betting favourite.

His main challenger appeared to be Roland Thornhill, the former mayor of Dartmouth and the MLA for Dartmouth South since 1974. Thornhill was a veteran of the party, having lost to Buchanan in the 1971 leadership contest. He had held a series of cabinet portfolios, most recently tourism. At first, it seemed like Thornhill would have to sit out the race — the RCMP was investigating him over an alleged deal he made with banks to settle his debts after he was appointed to cabinet.

Thornhill, though, didn’t care and he launched his campaign anyway. The investigation dogged him throughout, but he cast himself as the victim. He was the favourite of the long-standing members and closely aligned with Buchanan.

Also in the running was Donald Cameron, the MLA for Pictou East since 1974 and the industry minister. A dairy farmer in his mid-40s, Cameron was a confrontational, blunt and hot-tempered Tory. A good friend of Mulroney, he also had strong support from caucus.

Rounding out the list was an outsider: Clair Callaghan, the former head of the Technical University of Nova Scotia and a failed PC candidate in 1988. That defeat, though, meant Callaghan had none of the baggage of Buchanan’s government. While that might have been attractive to members eying the PCs’ awful polls, Callaghan’s campaign never gained much traction.

But even the insiders tried to make themselves out as outsiders, as both Cameron and McInnis attempted to distance themselves from the former premier. They both promised to clean up government and get rid of patronage, though Cameron’s pitch was weakened when a media report alleged a friend had received a lucrative government contract in his riding.

The prize the four men were fighting over wasn’t a glittering one. Kevin Cox, writing from The Globe and Mail’s Atlantic Bureau, wrote this up as the PC leadership job description:

Must be skilled in resuscitation techniques as well as renovating and house cleaning. Should stand up well under intense media and RCMP scrutiny. A scandal-free record helpful but hardly essential. This position will appeal to those willing to face a challenge: to restore public confidence in a patronage-tainted government now subject to an RCMP investigation, a slim hold on power and only 14 per cent of public support. Salary: about $97,000 per annum. Could be short-term employment.

PC delegates gathered on February 9, 1991 in a Halifax hockey rink to cast their ballots. Though no one knew for certain, the expected first ballot finish was Thornhill, McInnis, Cameron and Callaghan. It didn’t quite end up that way.

Perhaps weighed down by the RCMP’s ongoing investigation, Thornhill under-performed — as did McInnis. Cameron finished first with 754 votes, followed closely by Thornhill with 736, McInnis with 680 and Callaghan with 178.

Callaghan dropped off but it didn’t settle matters. The largest number of Callaghan’s supporters went to McInnis, who gained 82 votes. But he was stuck in third with 762, still 13 votes behind Thornhill. Cameron, with 801, was again on top.

With McInnis eliminated, most of his delegates went over to Cameron, who was promising the same hard line against past patronage. Cameron jumped 400 votes to 1,201, with Thornhill gaining just 283 votes and finishing second with 1,058.

The delegates’ were right to trust their gut — Thornhill would be charged by the RCMP later that month. Those charges would eventually be dismissed, but a Thornhill premiership would have been a tumultuous one.

Not that it mattered. Cameron would continue to lead the PCs for another two years until their inevitable defeat. Facing election in 1993 at the last possible moment, the PCs dropped to just nine seats, the party’s worst showing since 1945. Cameron held his own seat of Pictou East, but resigned as PC leader shortly after losing the premier’s office.

Short-term employment, indeed.

1997 Nova Scotia Liberal leadership

Nova Scotia Liberals choose MacLellan

July 12, 1997

It was a bad time to be a Nova Scotia Liberal.

When John Savage led the party to victory in the 1993 election, he took over a province facing numerous challenges. Four years later, after years of unpopular austerity and cuts, the Nova Scotia Liberals were third in the polls. With even his own party wanting him out, Savage had little choice but to step aside and kick-off a leadership race to name his replacement.

The date was set for July 12. But before that vote could happen, Jean Chrétien called the 1997 federal election. His party was able to narrowly secure another majority government, but that wasn’t with the help of Nova Scotia. The federal Liberals had swept the province in 1993. In 1997, the Liberals were shut out, losing all 11 seats to Jean Charest’s Progressive Conservatives and the New Democrats under Nova Scotia’s own Alexa McDonough.

So the race to replace John Savage was not a particularly upbeat campaign, to say the least.

There were two front runners for the post.

The first was Bernie Boudreau, a Cape Breton MLA first elected in 1988. He had held the finance and health portfolios in Savage’s cabinet. He was the first to throw his hat in the ring and had a majority of the Nova Scotia Liberal caucus behind him.

That, however, wasn’t exactly a good thing. Boudreau had been the face of the government’s drive to balance the budget and its closure of hospitals. He was the party establishment candidate and the defender of the unpopular Savage government. There was little appetite for that, both inside and outside the Liberal Party.

His main opponent was an outsider to provincial politics. Russell MacLellan, 57, was still well-known in Nova Scotia’s political circles as he had been a Cape Breton MP since 1979. Though he never held a cabinet portfolio, he had been a parliamentary secretary to various federal ministers.

There was also Roseanne Skoke, another former MP. She had been elected in 1993 in the riding of Central Nova but had lost her nomination bid to be the Liberal candidate again in 1997. Lastly, there was Bruce Holland, a Halifax-area MLA elected in 1993.

Both Skoke and Holland were sharp critics of the Savage government.

“We’ve run the province with an autocratic, arrogant attitude and as a result we angered everyone in the province and people just don’t feel good,” Holland said at the final of 10 leadership debates.

One of the biggest concerns in the race was about patronage appointments — not that they were given out, but rather that they weren’t. As premier, Savage promised not to make the kind of patronage appointments that his PC predecessors had done. That didn’t go over very well in Liberal circles.

“The elites in the party received their patronage appointments and our grassroots workers didn’t,” explained Skoke. “Political patronage is inherent in the political party system and it is imperative that we recognize and reward the faithful of this party. That is something the Savage government failed to do.”

While MacLellan was also critical of the Liberal government, he didn’t go as hard as Skoke or Holland. He ran a relatively low-key campaign, keeping his proposals vague and promising to listen to the grassroots of the party. His was a front runner’s campaign — or, at least, one of two front runners — and he nearly cruised to a first ballot victory.

MacLellan earned 4,978 votes on the first ballot, finishing with just under 49% of the vote. Boudreau was second with around 32% of the vote, while Skoke captured 17% and Holland finished with a little less than 3%.

It was clear that MacLellan was going to win, and to solidify that victory Holland endorsed the former Cape Breton MP. On the second ballot, MacLellan grew his total by 561 votes, seemingly taking from both Holland and Skoke, who saw her vote drop, and won with 56% on the second ballot. Boudreau finished with just 32%.

“We’re sending a message tonight that we’re back in business,” MacLellan told the crowd after his victory.

In some ways, he was right. Liberal support had tanked in the polls, but by the 1998 Nova Scotia election MacLellan was able to win a minority government, tying the NDP in seats and earning a mere 3,000 more votes than the New Democrats across the province. MacLellan remained in power with the support of the PCs until 1999, when his government was brought down and his party defeated in that year’s election.

The Liberals finally fell to that third spot, where they would remain for the next 10 years.

1999 Nova Scotia election

The doctor is in

July 27, 1999

In 1998, the governing Nova Scotia Liberals under Russell MacLellan held on by the slimmest of margins. The party won 19 seats, tying them with the NDP. It was only with the support of the Progressive Conservatives, who finished third with 14 seats, that MacLellan was able to keep his job as premier, a role he took over from John Savage only the year before.

It wasn’t the greatest recipe for a stable minority government. Sure enough, little more than a year after the 1998 provincial election, MacLellan’s government collapsed.

That collapse occurred when the PCs could no longer prop up the Liberals. The province’s health care system was in dire shape. While the budget showed a small $1.5 million surplus, the Liberals also planned to borrow $600 million over the next three years to pay for some new investments in health care. The PCs had expected a balanced budget, not increased deficits, and so pulled the plug. Along with the NDP, the PCs voted against the government and an election was set for July 27, 1999.

The cast of characters was a re-run of the 1998 campaign. MacLellan would lead the Liberals again, as would the NDP’s Robert Chisholm. John Hamm, a rural family doctor who became PC leader in 1995, would be the relative veteran of the three.

The campaign pitted balanced budgets vs. health care, a complicated debate in a province crippled by $9 billion in debt, a serious lack of physicians and nurses and too much outdated equipment in the health care sector that needed to be replaced. The MacLellan government had a record of spending with little to show for results. The NDP had a reputation for demanding even more spending. Hamm and the PCs promised balanced budgets (and a tax cut), but the memory of the austerity years under former PC premier John Buchanan weighed heavily on Nova Scotians.

The polls suggested it would be another tight, three-way contest. At the outset, though, it seemed like the fight was primarily between MacLellan and Chisholm.

It wasn’t a great match up for MacLellan — he wasn’t particularly dynamic on camera, especially compared to the young and energetic Chisholm. Hamm was much more low key, but there was an earnestness about him.

The summer was unseasonably warm, which made for a sweaty campaign. Despite having brought the government down, the Tories and New Democrats seemed unprepared and were slow to get their candidates nominated. MacLellan and Chisholm hit the road in campaign vans; Hamm used an RV.

The turning point of the election might have been the leaders debate. It was an acrimonious affair between MacLellan and Chisholm, with the Liberal leader uncharacteristically going on the attack. It was a pitched battle between the two that left Hamm on the sidelines — wading into the fray just wasn’t in his character. The post-debate pundits pegged Hamm as the loser because of his lack of presence, but in an ugly fight between the Liberals and NDP, his calm, quiet demeanour was just what Nova Scotians were looking for in a leader.

With the Liberals faltering, the contest was becoming one between the PCs and NDP — just the kind of thing that could bleed even more Liberal support over to the Tories. Chisholm’s campaign was going well. He cast himself as a prudent spender with more pragmatic plans for health care reform than the deficit-spending Liberals, and New Democrats from across the country were making their way to Nova Scotia to pitch in to try to elect the province’s first NDP government.

Chisholm’s campaign hit a speed bump, though, when it was leaked that he had a drunk-driving conviction from 22 years earlier. While that alone might not have been the biggest bombshell, it contradicted what Chisholm himself had said at the campaign’s outset, when a newspaper asked all the leaders a series of personal questions, including whether they had ever been convicted of a crime. Chisholm said he hadn’t.

As election day approached, confident predictions of who would come out ahead were few and far between. Another minority government seemed likely in this three-way race, but forecasting the outcome of a sleepy summer campaign seemed unwise.

That the PCs emerged victorious was a bit of a surprise — that they got a majority was a shock.

The Progressive Conservatives captured 30 seats, more than double what they had won in the 1998 campaign the year before, and saw their popular vote jump nine points to 39.2%. All but three of the 12 seats the Liberals had won on the mainland in 1998 flipped to the PCs. The Tories even made gains in Halifax, including the downtown riding of Halifax-Citadel.

But it was a close-run thing — the four seats that gave Hamm his majority government were decided by little more than 200 votes altogether. The winner in Shelburne had to be decided by a random draw when recounts left the PC and Liberal candidates tied with 3,206 votes apiece.

Though the PCs had won seats in every part of the province, their gains on Cape Breton were limited: just a single seat turned blue. Liberal losses in Halifax and in rural Nova Scotia were mitigated by gains at the expense of the NDP in and around Sydney, where MacLellan’s government had invested significant funds in the city’s struggling steel mill. The result was that the Liberals and NDP ended in a tie once again, but this time with just 11 seats apiece. The New Democrats edged the Liberals out in provincewide support by a few hundred votes.

Both Chisholm and MacLellan said they’d stay on as leaders on election night, but they’d both be gone by the following year.

Flushed with victory, Hamm thanked all of those who had backed his political career in the past, saying “they are the reasons why, in six short years, to my own surprise, I have gone from being a shy rookie MLA to standing before you as premier-elect.” Hamm would stay in the job for another six years, with one more election — resulting in a return to unstable minority government — ahead of him.

2004 Nova Scotia Liberal leadership

MacKenzie defeats Mann

October 23, 2004

When Danny Graham announced he was stepping down as leader of the Nova Scotia Liberals due to the health challenges his wife was facing, his party had been out of power for five years. Like their federal cousins, the Nova Scotia Liberals came to office in 1993 at a low point for Progressive Conservative parties from coast to coast. But the Liberals quickly became unpopular themselves after imposing austerity on the province and were reduced to the barest of minorities in 1998. A year later, the Liberals were voted out entirely.

Graham took over the Liberals in their weakened state and could do little to help the party in the 2003 provincial election, when they finished third behind the New Democrats with just 31.5% of the vote and 12 seats. John Hamm’s PCs secured a minority.

That did mean that an election could be held at any point — and that the third party in the legislature held one of the keys to bringing the government down. Whoever took over the Liberal leadership could be put to the test very soon.

Only two candidates, however, stepped forward and stayed in the race through to its completion on October 23, 2004. One was Richie Mann, a former Liberal cabinet minister from Cape Breton who had left politics before the 1998 election. He was the experienced insider in the race.

The other was Francis MacKenzie, the inexperienced outsider. MacKenzie, a Halifax-based business executive (also originally from Cape Breton), had never held elected office before. He knew his way around a leadership contest, however, as he had run for the leadership in 2002. He finished second to Graham with about a third of ballots cast. Now he was back.

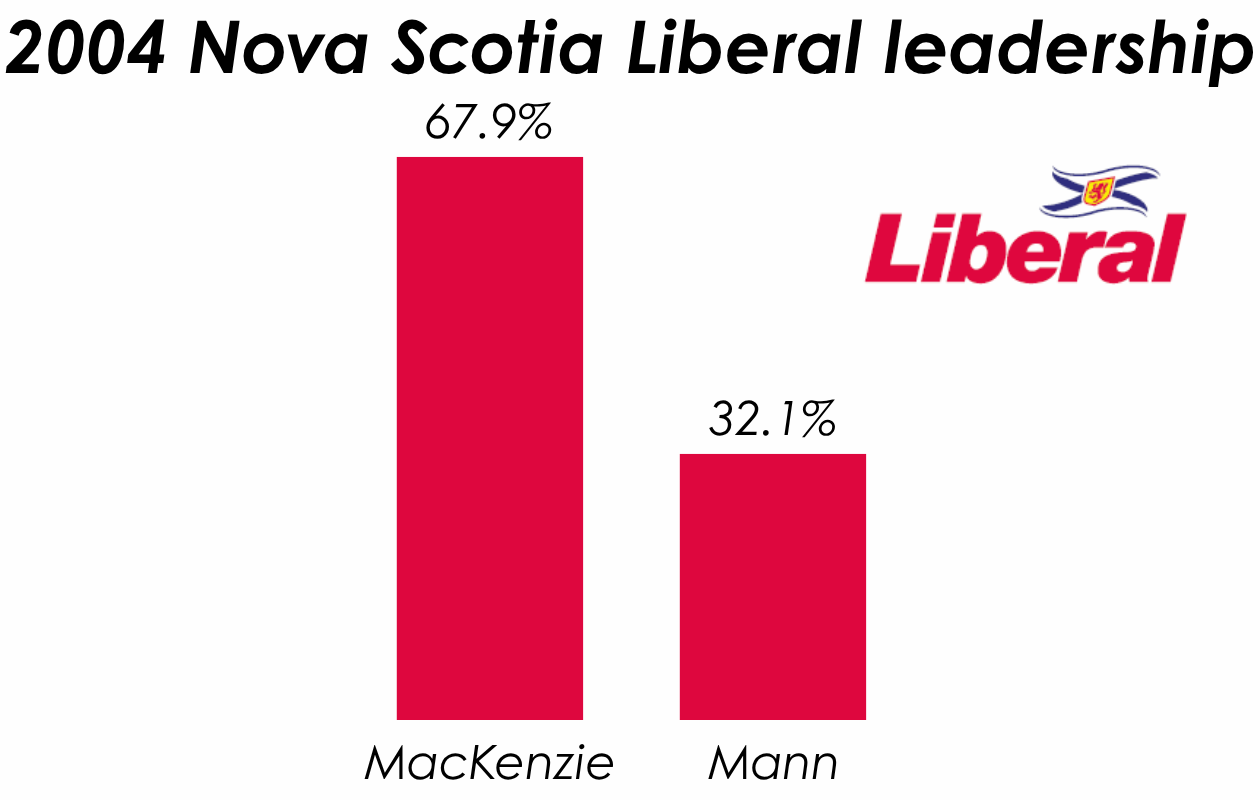

But there wasn’t much enthusiasm for the race within the party. The Nova Scotia Liberals used a one-member, one-vote system without any weighting applied to the province’s ridings. When the votes were tallied and the result announced at the party’s convention in Halifax, only some 7,500 had bothered to cast a ballot — and reportedly half of them were cast by Cape Bretoners.

Turnout was down from about 11,500 in 2002, with roughly one-third of eligible voters participating. The result was a clear win for MacKenzie, who captured 68% of the vote to Mann’s 32%.

“Wow. Thank you, thank you, thank you everyone,” said MacKenzie after he was named the winner. “It takes my breath. It’s quite an honour here, and it’s quite a moment for me.”

MacKenzie wouldn’t have much luck as leader of the Liberals. While he would keep his party competitive in the polls in Nova Scotia’s three-way race over the next few years, support for the party collapsed in the 2006 election and the Liberals lost seats and vote share as Darrell Dexter’s NDP solidified its position as the PCs’ main opponent. It would take two more elections (and one more leader) before the Nova Scotia Liberals would get themselves back into power.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Nova Scotia and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Joseph Howe, Volume II: The Briton Becomes Canadian, 1848-1873 by Murray Beck

The Man from Halifax: Sir John Thompson, Prime Minister by P.B. Waite

Sir Charles Tupper: Fighting Doctor to Father of Confederation by Jock and Janet Murray

Robert Laird Borden: A Biography, Volume 1 by Robert Craig Brown

Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal by T. Stephen Henderson

Robert Stanfield’s Canada: Perspectives of the Best Prime Minister We Never Had by Richard Clippingdale

Nova Scotia Politics, 1945-2020: From Macdonald to MacNeil by Graham Steele