#EveryElectionProject: Newfoundland and Labrador

Capsules on Newfoundland and Labrador's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Newfoundland and Labrador.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1959 Newfoundland election

Joey vs. Dief

August 20, 1959

Marking 10 years as the last province to join Confederation, Newfoundland didn’t have much to celebrate in 1959. Poorer than the country it joined in 1949, Newfoundland had fallen further behind the rest of Canada over the next 10 years. The economy was in the doldrums and unemployment was soaring.

Joey Smallwood, the only premier the province had ever known, had to find someone to blame. John Diefenbaker would do just fine.

The Progressive Conservatives had won a landslide victory in the 1958 election, but they didn’t do so well in Newfoundland. Throwing his weight behind his federal Liberal cousins, Smallwood ensured that Diefenbaker won only two seats in the province — making it the only province in that election that didn’t elect a majority of PC MPs.

One of the terms of Newfoundland’s union with Canada — Term 29 — became the flashpoint issue that Smallwood needed to deflect Newfoundlanders’ unrest toward someone else. Term 29 ensured that Newfoundland received funding from the federal government to help ensure the delivery of services that were up to par with what was available elsewhere in Canada. But the terms were somewhat vague. The Diefenbaker government decided that the terms of the agreement would run their course in 1962 after some $36 million was sent to St. John’s. After that, the federal government would reconsider Newfoundland’s needs.

To Smallwood, this was betrayal of the terms of union. He demanded that transfers continue in perpetuity, even if they were still not enough.

The issue split the provincial Progressive Conservatives in Newfoundland. Malcolm Hollett, the party’s leader, stuck with Diefenbaker and the prime minister’s pledge that Newfoundland would be treated equitably. Another PC MHA stood with Hollett. But two others — representing half of the remaining PC caucus in what was a largely one-party state — broke with the provincial Tories, and set up their own party: United Newfoundland.

James Higgins, one of the breakaway MHAs, argued that Newfoundland needed a party divorced from federal politics. He didn’t support Diefenbaker, but he wasn’t ready to support Smallwood.

But a canny strategist like Smallwood knew an opportunity when he saw one. Calling them “patriotic men who put Newfoundland first” and promising that “anyone with the smell of Diefenbaker on him is good and finished”, Smallwood ensured that the two UNP incumbents would not face a Liberal opponent in their own ridings.

Not so the PC leader. When the Tories voted against a resolution condemning the Diefenbaker government’s decision on Term 29, Smallwood dissolved the legislature and sent the province to the polls. To make his point, Smallwood wouldn’t run in his own district of Bonavista North, but would take on Hollett on his own home turf in the Tory heartland of St. John’s West.

“We will see who speaks for Newfoundland — Mr. Hollett or yours truly,” he said.

There was another new party on the ballot in the 1959 provincial election. The Newfoundland Democratic Party, backed by the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, was formed as a result of the loggers’ strike that had caused great unrest and violence in the Grand Falls area earlier that year. The party’s leader, Ed Finn Jr., even ran against the labour minister.

But though the strike had captured Newfoundlanders’ attention earlier in 1959, on the campaign trail Smallwood ensured that the only issue was Term 29 — and that a vote against the Liberal Party was the same as a vote against Newfoundland itself.

Smallwood took nothing for granted. In Smallwood: The Unlikely Revolutionary, Richard Gwyn wrote that “for the first time he experienced with television on a large scale, delivering five-minute speeches each night. In St. John’s … he canvassed by car and gave as many as six street-corner speeches a day. To reach those who remained indoors, a squad of Liberal workers telephoned householders and told them: ‘This is a message from the Premier,’ and then switch on a five-minute tape recording. Some listeners, who assumed the caller was Smallwood in person, tried to interrupt him with questions, and inspired Hollett to the best crack of the campaign: ‘That’s typical of Smallwood, he never listens.’”

The result was another landslide for Joey. The Liberals’ share of the vote fell by eight points, but most voters still backed the party. They won 58% of the vote and 31 seats.

The PCs won three seats, one fewer than in 1956 but one more than they had at dissolution, with 25% of the vote, as United Newfoundland captured another 8% and managed to win two seats. Higgins, however, was not one of them — he was beaten by a Tory.

In fact, Smallwood was the only party leader to win his seat. The Newfoundland Democrats did far better than the CCF did in 1956 with 7% of the vote, but failed to elect a single candidate. The fight in St. John’s West between Hollett and the premier went Smallwood’s way by a margin of two-to-one.

“I am sorry to see Mr. Hollett defeated as a man,” Smallwood said after the returns came in, “but more than pleased about the defeat because Mr. Hollett chose to hold himself out as a spokesman for Mr. Diefenbaker.”

With the election behind him, Smallwood let the issue of Term 29 faded away. There was not much he could do against Diefenbaker’s majority in Ottawa. Resolution of the issue would have to wait until Lester Pearson’s Liberals came to power in 1963, when they agreed to keep the money flowing. Maybe it was to repay a favour — Pearson’s Liberals swept all seven of Newfoundland’s seats in that election.

1966 Newfoundland election

Newfoundland gives their hero a last hurrah, but he won’t stay away

September 8, 1966

It was supposed to be Joey Smallwood’s last hurrah. The voters planned to send him off in style, giving the man who brought Newfoundland and Labrador into Confederation his biggest landslide. It was the pinnacle of Smallwood’s political dominance of the province, which had in many ways become a one-party state.

There was more than just affection and, just maybe, fear that gave the Liberals such a big victory in the 1966 Newfoundland election. The economic mood of the province was upbeat and the future looked bright. In the months ahead of the election call, Smallwood announced a new fish plant here and the expansion of an iron ore plant there. He announced that more electricity power would be produced and that a new phosphorus industry was going to be developed.

There had been investment in education with free tuition for first-year students at Memorial University, which was also about to get a new faculty of medicine.

Why would Newfoundlanders want to ruin all that by doing something as silly as voting for the opposition?

James Greene, who led that small contingent of Progressive Conservatives on the opposition benches in the House of Assembly, resigned in January 1966, “pleading pressure of private business.”

His replacement was Noel Murphy, who had won his seat of Humber East in the 1962 provincial election — the first time the Liberals had failed to take it. A former medical officer for the Royal Air Force’s Newfoundland squadron, Murphy was aching for a duel with Smallwood.

Rumours were circulating that Smallwood might step aside before calling an election. In response, Murphy said that he didn’t “want him to resign from office undefeated and go down in history as a legend. I want him to be defeated at the polls and this is what the Conservative Party is working toward right now.”

“It’s about time that the people of Newfoundland realize that the Liberals are not the only ones capable of forming a Government.”

Smallwood wouldn’t step aside, at least not yet, and kicked off the three-week election campaign in August 1966.

The Liberal platform, which Smallwood dubbed “the greatest political document in Newfoundland’s political history”, was a 41-page booklet that included promises of 4,000 miles of newly paved and constructed roads, including a tunnel that would connect Newfoundland to Labrador (paid for by the feds). The Liberals would build and renovate hundreds of schools, expand the province’s health services and lower electricity costs.

Flush with cash, the Liberals printed 100,000 copies of the platform and stuck 50,000 of them into the mail for voters to peruse.

Smallwood also said that he was “positively preparing to step down as soon as these kiddies [young Liberal candidates] have made up their minds what they are going to do and are ready to do it.”

These “kiddies” included newly-minted cabinet ministers like Clyde Wells, 28, and John Crosbie, 35.

But in case voters weren’t feeling grateful to Joey and the Liberals, the premier who had easily won every election held since Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949 made it clear what a lack of gratitude could mean.

To the voters of Stephenville, where the U.S. Air Force had just shuttered an airbase, Smallwood wrote a letter:

The minute [the U.S.] left it became my job to save that part of Newfoundland from unemployment, destitution, dole, despair and finally the disappearance of much of its population…. Will you help me to do it? Or do you want to send me a message saying, “Stop. We don’t need your help.” … That will be the answer you will give me if you elect the Tory candidate, or the Independent Liberal candidate. If you want to send me a message saying: “Yes, Joe, we want you to keep on working hard for this District and the people in it,” the only way you can send me that message is to elect the Liberal Party’s candidate.

Murphy and the PCs had little to fight back with and Murphy took to calling Smallwood a “tyrant” and a “dictator”. The New Democrats ran only three candidates and were led by Calvin “Tubby” Normore, who was taking on Smallwood in the riding of Humber West. According to the Canadian Press, this former amateur wrestler “was named leader of the New Democratic Party only three days after the election was called. He has no political background.”

There was some drama during the campaign when former Quebec premier Jean Lesage said that negotiations between Quebec and Newfoundland had included discussion of changing the borders of Labrador. Smallwood didn’t hold back, calling Lesage “a liar from head to toe”. The former premier eventually clarified that the negotiations didn’t include border adjustments.

By the end of the campaign, there was little doubt that Smallwood would win again. He had now upgraded his musings about retirement to “definitely”, and had even said his chosen successor would be Fred Rowe, the finance minister. All Newfoundlanders had to do was send Joey off into the sunset.

And that they did, giving the Liberals 39 of 42 seats and nearly 62% of the vote. The Liberals picked up five seats, reducing the Progressive Conservatives to just three seats, all of them in the St. John’s area. The NDP and various independent candidates were shut out.

Reflecting on the results, Smallwood said it was “a sobering victory because how am I going to measure up to such overwhelming confidence?”

To be fair, the Canadian Annual Review noted that “the opposition did not really offer a reasonable alternative government to the electorate, which can be explained, in part at least, by the fact that most of the truly promising young politicians have been attracted, by one means or another but basically by the guarantee of success, to the Liberal Party.”

Murphy went down to defeat in Humber East, beaten by future premier Clyde Wells. His campaign was also made all the more difficult by Smallwood deciding he would run in the neighbouring riding. Smallwood wasn’t going to take any chances by letting the leader of the opposition win his own seat.

It would prove to be Smallwood’s last victory. He eventually announced his retirement in 1969 but reversed his decision and ran for the leadership of the Liberals in order to block the candidacy of John Crosbie, one of his former “kiddies”. Smallwood beat Crosbie, split the party in two and met his defeat when, in 1971, Newfoundlanders finally did realize that the Liberals were not the only ones capable of forming government.

1969 Newfoundland Liberal leadership

Only Joey can replace Joey

November 1, 1969

Joey Smallwood, the man who led Newfoundland into Confederation in 1949, was approaching two decades as the premier of Canada’s newest province in 1968. His political dominance of Newfoundland had rarely been challenged over the preceding years, but signs of rebellion were starting to show in his kingdom.

It didn’t help when he strong-armed his own Liberals to back Pierre Trudeau in that year’s federal leadership contest. Many of them preferred Robert Winters, but once Smallwood had decided that Trudeau would be his candidate he brooked no dissent.

One of those who was upset was John Crosbie, a young minister in his cabinet, and he quit over a dispute with Smallwood over a questionable loan the government was proposing to give to a developer. He was joined in his resignation by Clyde Wells.

Hailing from a distinguished family as Crosbie did, Smallwood was proud to have him serving in his cabinet. But that pride was not reciprocated. According to Richard Gwyn, writing in Smallwood: The Unlikely Revolutionary,

“For a full year before he quit, Crosbie left little doubt of his dissatisfaction as he mocked Smallwood, with astonishing indiscretion, round the St. John’s East cocktail circuit. The stories all found their way back to Smallwood, but he took no action. He could not afford to. As Minister of Municipal Affairs, and later of Health, Crosbie came to dominate cabinet. A glutton for work, he won arguments by force and sheer dogged persistence. At the same time, outside the cabinet, investors and businessmen looked to him for leadership and sanity. As the government’s financial troubles deepened, Crosbie became that rarity in any Smallwood cabinet, the almost indispensable man.”

But not only was Smallwood’s control over his cabinet starting to fray. In the 1968 federal election, Newfoundlanders shocked Joey when they elected six PC MPs — nearly as many in one election as had ever been elected in Newfoundland over the previous seven. It was an embarrassing rebuke, and Smallwood announced that he’d call a leadership convention for the next year.

John Crosbie threw his hat into the ring, as did Fred Rowe, a senior minister in Smallwood’s cabinet. But Joey hoped that Don Jamieson, the leading Liberal MP from Newfoundland in Ottawa, would quit federal politics to take up the mantle.

Jamieson, however, would not definitively make up his mind. And as Crosbie toured the province criticizing the work that Smallwood had done over the last 19 years, Smallwood seethed. He couldn’t risk handing over the keys to his province — and it was his, of course — to a rogue, a “rat” like Crosbie. When Jamieson refused Smallwood’s entreaties one last time, the premier threw his own hat into the ring, and Rowe meekly stepped aside.

The campaigning between Crosbie and Smallwood was an all-out civil war, with Smallwood relying on his traditional backers in the outports who had decided for Confederation, Crosbie on the young and the well-heeled. Incredible sums of money were spent by both candidates, with total spending on this leadership race topping $1 million. Both Crosbie and Smallwood spent more money trying to win the leadership of the Newfoundland Liberals in 1969 than any candidate did to try to become the national Liberal leader in 1968.

The battle came down to fighting for delegates in each district across the province, but as the delegates were being elected it became clear that Smallwood would have a big advantage — an insurmountable one — at the convention in St. John’s. The old levers Smallwood could always pull within the Liberal Party were working in his favour, even if Crosbie’s campaign was more professional and modern.

But it was an ugly fight. So ugly that Alex Hickman, another member of Smallwood’s cabinet, joined the race in its late stages in the hope of being a consensus candidate between the two polarized wings of the party. (Three other candidates, Randy Joyce, a university student, and businessmen Peter Cook and Vincent Spencer, were running but had little support.)

The money kept flowing when nearly 1,600 Liberals gathered for the convention. Alcohol was readily available at the Crosbie and Smallwood hospitality suites (Hickman’s coffee and sandwiches weren’t nearly as popular) and the Smallwood campaign rented some passenger train cars to supplement the over-booked hotels in the provincial capital.

The result went just about as expected after the delegate elections had so heavily favoured Smallwood. He took 62% of the delegates’ votes, followed at length by Crosbie with 26% and Hickman with 11%. It wasn’t a resounding, convincing victory — nearly two out of every five delegates had voted against the only leader the party had ever known — but it was a victory nonetheless. Smallwood wouldn’t give up his grip on his province so easily.

But the campaign had deeply divided the party. After the results were announced, Crosbie’s supporters booed and nearly rioted in the hall once Smallwood had exited, chanting slogans and spitting on a cabinet minister, all in front of the media’s cameras.

Smallwood’s vengeance was swift. Crosbie was booted out of the party and Hickman and the sole minister who endorsed him didn’t return to the cabinet table. Karma, however, would come back to bite Smallwood. In 1971, both Crosbie and Hickman would stand as PC candidates in the election that would ultimately end his premiership — for real this time.

1982 Newfoundland election

Peckford wins big for the PCs

April 6, 1982

In 1982, the era of Liberal rule under Joey Smallwood was already a decade in Newfoundland’s past. The Progressive Conservatives had governed the province since Smallwood’s defeat and had already changed leaders once after a 36-year-old Brian Peckford succeeded Frank Moores shortly before the 1979 provincial election.

But after less than three years in office, Peckford was still struggling with a sluggish economy and disputes with the federal government over offshore resource development.

So, in a television address Peckford announced he was calling an election to be held just three weeks later in order to send a message to Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government.

“What I need now, he said, “is a clear mandate which will show Ottawa that you do support my administration and the stand we are taking.”

The federal government was claiming full control over offshore resource development. Instead, Peckford proposed revenue-sharing between St. John’s and Ottawa and said he would make it the one issue of the election.

With every incumbent PC MHA running again in a quick campaign, the Progressive Conservatives held all the advantages. Nevertheless, Peckford had to defend his decision to call an early election only 2.5 years after the last one.

Len Stirling, the Liberal leader, charged that the issue for voters wasn’t the control of offshore resources but whether Newfoundlanders wanted to “go to war or go to work.” He accused the PCs of ignoring more immediate issues like the fate of the inshore fishery or the mining industry on the island, and proposed a less confrontational approach with the feds.

The opposition, which included the New Democrats under Peter Fenwick, tried to make the campaign about other issues and faced off with Peckford in a televised debate that got less than rave reviews — The Daily News editorial had only this to say: “Blah.”

But attempts to make the campaign about the immediate joblessness scourging the province rather than the resources that would only start paying off years down the road were largely unsuccessful, especially when Peckford announced his own measures late in the campaign to try to support the fishery.

The anti-Ottawa sabre-rattling was very effective, and on April 6, 1982 the Progressive Conservatives won what was their biggest victory at the time, and one that has only since been surpassed once (by Danny Williams in 2007).

With turnout jumping to 78%, the PCs secured 44 seats, a gain of 11 over their performance in the 1979 election, entirely at the expense of the Liberals outside the Avalon Peninsula, which the PCs had already swept the last time. The party was also up 11 points in its vote share, capturing 61% of ballots cast.

The Liberals suffered their worst defeat up to that time, dropping 11 seats to just eight and falling six percentage points to only 35% support. Stirling was one of the defeated Liberals, and he announced his intention to resign.

Fenwick’s New Democrats ran less than half of the slate of candidates as they had in 1979 and accordingly saw their share of the vote drop by four points to 4%. The NDP placed second in only two ridings, and in neither case were they even close to winning.

It was a big, sweeping victory for Peckford which, he argued, gave him the powerful mandate he needed in his negotiations with the federal government.

“Newfoundland speaks with one voice,” he said on election night, “when we say that one day the sun will shine and have-not will be no more.”

But Peckford would have no success in renegotiating its deal with Quebec over revenues from power generation in the Upper Churchill, and the cod stocks would collapse a few years after his departure as premier. The strong mandate voters gave him in 1982 did nothing to help him with the Trudeau-Turner Liberals, and he would have to wait until the arrival of Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government in 1984 for Canada and Newfoundland to sign an agreement that made the two levels of government joint partners in developing the oil and gas fields off the coast.

And it was not until 1997 that oil would begin to flow at Hibernia, 15 years after the “one-issue” Newfoundland election of 1982.

1987 Newfoundland Liberal leadership

All’s well that ends Wells

June 6, 1987

For the first few decades of Newfoundland’s history, the Liberals were absolutely dominant. But once Joey Smallwood, the man who took the province into Confederation, couldn’t take the hint and outstayed his welcome in the early 1970s, the Liberal Party was in rough shape — internally divided and externally unpopular.

Things didn’t get much better when Smallwood finally called it quits as the Liberals went through a succession of unsuccessful leaders while the Progressive Conservatives, first under Frank Moores and then Brian Peckford, won election after election. The increasing unpopularity of the federal Liberals was also taking its toll.

In 1985, the Newfoundland Liberals lost another election, this time under the leadership of Leo Barry. He had been a PC cabinet minister but resigned from Peckford’s government in 1984 and found himself leading the Liberal opposition a few months later. Barry nearly doubled the Liberals’ seat total, but Peckford won another majority government.

Before long, Barry’s caucus was in open revolt against his heavy-handed leadership. They unanimously called for his resignation when he decided to make a trip to Boston while the House of Assembly was sitting and, in early 1987, he called for a leadership convention in June to settle the matter. He’d stand as a candidate, which pleased no one.

It was in the midst of this tumult that Clyde Wells finally decided to take the plunge. He had served as a minister in Smallwood’s government, but quit cabinet (along with John Crosbie) over his leadership. Crosbie would unsuccessfully challenge Smallwood for the title and eventually crossed the floor to the PCs, but Wells went back to practising law instead, first in Corner Brook, then in St. John’s.

He was often courted to run for the Liberal leadership, but he didn’t want to give up his lucrative practice. But he was finally ready to return to politics — for a price.

He announced his candidacy in April, backed by former leaders Steve Neary and Ed Roberts, along with the three MHAs. He was one of three candidates in the running, the others being Leo Barry and Winston Baker.

Baker was new to provincial politics, having been elected in Gander in 1985, but the Baker name wasn’t new, as his brother George had been the Liberal MP for Gander–Grand Falls since 1974.

The ballot got winnowed down to two before the end of April with the withdrawal of Barry, who blamed the caucus for causing him “irredeemable damage”. But he didn’t go without a parting shot at Wells, who wanted his lost income from leaving his practice (estimated to be about $200,000 at the time) to be covered by the party.

“Unless the funds come out of general Liberal Party revenues,” said Barry, “…the general party membership and indeed the general public must be informed of the source of such funds, keeping in mind that he who pays the piper calls the tune.”

It was really the only issue of the leadership campaign, and ahead of the convention Wells sent a letter to delegates explaining how a group of Liberal supporters had promised to raise the money to cover half of his lost salary.

“I suppose I could do it on $100,000,” Wells said. The salary for an opposition leader at the time was about $70,000.

The convention was held at the Mary Queen of Peace parish hall (“undersized”, according to the Canadian Press correspondent), and Baker agreed that he was the underdog. Nevertheless, he predicted he would get hundreds of ballots. Wells predicted he’d win an easy majority.

“If posters were any indication,” wrote Robert Martin in The Globe and Mail, “Mr. Wells is a shoo-in. His large, full-color [sic] portraits, featuring his startlingly blue, John Turner-like eyes, completely overwhelmed Mr. Baker’s modest little signs that said simply ‘Baker’”.

The result was an absolute landslide. Wells won 88% of the 643 ballots cast, with Baker managing only 67 votes. Ted Noseworthy, a marginal candidate who didn’t even show up to a leadership forum the day before the convention, received 10 votes.

It was the result everyone was expecting, and Wells told the audience to “take heart, Newfoundland, the Liberals are coming.”

But after the party’s recent history of revolving-door leadership, Wells also had a warning for the delegates.

“The days of saviors [sic] and messiahs are over,” he said. “If ever they existed, they don’t any more.” He alerted the delegates that winning the election would be the work of more than one man.

Whether or not he was the saviour, Wells did bring the Liberals to the promised land. It wasn’t quite the same landslide victory that he scored in the leadership race, but Wells would lead the Liberals back to power in 1989, promising to forego his salary top-up if elected premier.

1989 Newfoundland election

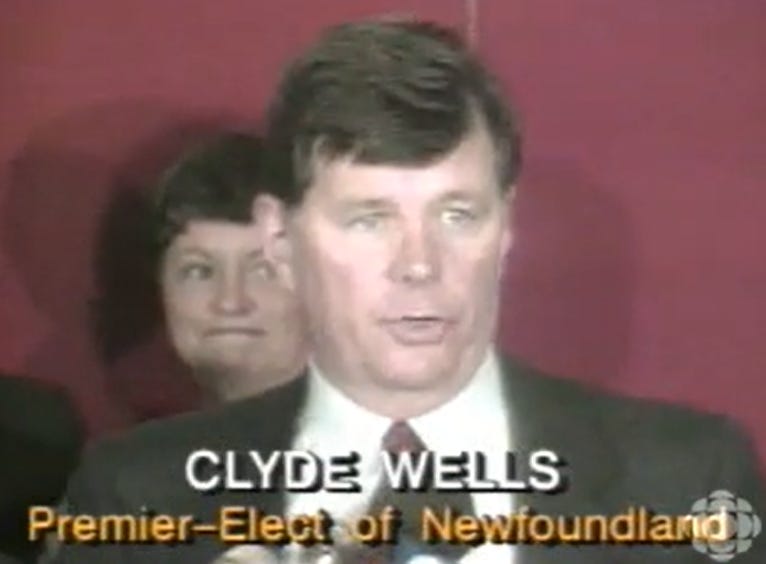

Clyde Wells in, Tom Rideout out

April 20, 1989

After 17 years in government and a decade of Brian Peckford in the premier’s office, the Progressive Conservatives in Newfoundland made a change in 1989. In a leadership contest that pitted five cabinet ministers against each other, it was the youngest at 40 years of age — Tom Rideout — who emerged as the winner.

Rideout, who was “gifted with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's broad chin but none of his rhetorical flourishes,” took over a province (and a party) that faced many challenges. There were the collapsing cod stocks, the continued delays in getting the Hibernia oil project up and running, expected cuts to federal transfers as the Mulroney government tightened its belt, and the $22 million money-pit Sprung Greenhouse project that would earn Rideout the sobriquet “Mr. Cucumber” on the campaign trail.

Rideout had pledged that he would seek a mandate of his own as soon as possible, and promised that his would be a leaner, more frugal administration — something he signalled immediately when he requested the resignation of four cabinet ministers and didn’t replace them.

But after so long in government and fresh off the heels of a closely-fought leadership race, the Progressive Conservatives had plenty of baggage and were riven by fissures from the leadership contest.

Nevertheless, with an internal poll giving his PCs a 21-point lead over the opposition Liberals, Rideout dissolved the House of Assembly about a week after he was sworn in as premier, kicking off a three-week election campaign.

The Newfoundland Liberals, who hadn’t won a vote since the days of Joey Smallwood, were now under the leadership of Clyde Wells, a former member of Smallwood’s cabinet.

Wells had returned to politics after a 16-year hiatus to take over the Liberal Party in 1987, being enticed in part by a $50,000 annual stipend provided to him from party coffers. Wells was criticized for this, and had to promise that he’d forego the bonus if elected premier.

Still, the Liberals were optimistic heading into the campaign. They were united behind Wells and organized, having all of their candidates nominated before Rideout’s PCs.

Wells promised a series of new programs targeted at equalizing services between rural and urban areas in the province. He had to spend a great deal of the campaign on the western coast of Newfoundland fighting to win the riding of Humber East, his old seat, taking on deputy premier Lynn Verge in the process.

The campaign injected some new, unexpected energy into Wells, and the crowds he attracted were moved by his rhetoric. Speaking in Corner Brook, he said “there's not a person here who doesn't have a brother or a sister or a son or a daughter who had to leave because there hasn't been any opportunity in this province to make a living in the last 10 years.”

Tapping into those emotions revolving around emigration and the economic struggles in Newfoundland, Wells laid the blame at the feat of the long-in-the-tooth PC government.

Also needling Rideout was the New Democratic Party under the newly-minted leadership of the “professorial” Cle Newhook. The NDP, though, was low on funds and Newhook had to limit his campaign to the St. John’s area, where he was running for a seat and where the only incumbent NDP MHA was on the ballot.

A TV debate settled little, with Wells and Newhook keeping Rideout on the defensive.

The Newfoundland PCs got little help from the federal government in the midst of the campaign, as the Mulroney PCs agreed to let the French increase their fishing hauls off the coast of the province, delayed signing an agreement that would have funded Hibernia and announced cuts to unemployment insurance in their federal budget. A late campaign visit by federal cabinet minister John Crosbie to announce new spending in St. John’s didn’t seem to do much good.

The PCs lacked incumbents in almost a dozen ridings and their campaign seemed stilted and unimaginative compared to the Liberals’ well-calibrated machine. The party was also dogged by a case involving sexual assault by social workers in western Newfoundland and rumours that the PC government had tried to cover it up.

But it was those cucumbers at the Sprung Greenhouse that were perhaps the biggest symbol of the PCs’ struggles. A Liberal ad, featuring a shrivelling cucumber, concluded with the message “Enough is enough. Vote Liberal for a real change."

The final polls of the campaign showed either a neck-and-neck race between the two parties or a PC advantage. But the momentum clearly appeared to be on the Liberal side.

When the ballots were counted, the result was close — at least in the vote count. The Liberals finished with 31 seats, a gain of 16 since the 1985 provincial election. The party captured 47.2% of the vote, up 10 points, but that still put the Liberals narrowly behind the PCs, who were down a single point to 47.6%.

However, the PCs dropped 15 seats and ended up with just 21, as the Liberals picked up eight seats in and around St. John’s and won four more seats from the party elsewhere on the Avalon Peninsula. Liberal gains were also scored in the north and west of the island — though not in Humber East, where Wells fell 143 votes short of Verge.

Rideout was re-elected with 82% of the vote in Baie Verte-White Bay, and said he intended to “lead this party vigorously into the 1990s”, though he would resign in early 1991.

The NDP was shutout and saw its share of the vote fall 10 points to just 4.4%. Newhook would stay on until 1992.

The Liberals were finally back in power after sitting in the opposition for nearly two decades, and they’d remain in office until 2003. In the immediate aftermath of the 1989 election, however, Wells’ win marked a shift in the national campaign to pass the Meech Lake Accord. Wells opposed it, and his victory gave new energy to the drive to see Meech Lake go down to defeat. When it did, it was another nail in the coffin of Brian Mulroney’s PC government — a nail Mulroney helped hammer in when he failed to make things easier for Tom Rideout and his cucumbers.

1993 Newfoundland election

Tough love rewarded

May 3, 1993

When Clyde Wells ended a 17-year Tory dynasty in 1989, he appealed to the hearts of Newfoundlanders. For too long, their children had to leave Newfoundland to find work. He would end that, bring those jobs back home and begin the province’s economic recovery.

Four years later, things were still going badly.

Unemployment stood at 20% and thousands more were out of work than when the Liberals came to power. Cuts had to be made to the public sector to try to keep the government’s deficit from ballooning too much.

Contrary to the usual practice of announcing a ‘good news’ budget ahead of an election, Wells’s government instead introduced another tough dose of fiscal medicine that included spending cuts, the postponement of construction projects to build new hospitals and schools and reductions in pension contributions to civil servants and teachers.

The economic headwinds were just too strong — a recession, the collapse of the fishing industry and the reduction in federal transfers had limited Newfoundland’s options.

For PC leader Len Simms, it was a depressing budget.

“It’s certainly gloom and doom,” he said, “and there is no message of hope.”

Simms, a former cabinet minister in Brian Peckford’s PC government, had replaced Tom Rideout in 1991 a few years after Rideout’s election defeat at the hands of Wells. But despite the pessimism from the premier, not even this affable, approachable PC leader could make a dent in the Liberals’ popularity.

The polls were giving the Liberals a huge lead over the PCs. Wells was popular in Newfoundland, some might even say revered. He was a hero, not only in Newfoundland but in other parts of Canada, when he played a hand in sinking the Meech Lake Accord. After coming to power, he let the accord that his predecessors had negotiated die without ratifying it before the deadline.

Buttressed with favourable polls, Wells launched the 1993 election campaign casting himself as the only leader willing to make the hard decisions that needed to be made. He directly challenged the Newfoundland Teachers Association that was opposing his cuts, arguing that the pain had to be spread around fairly. Would Newfoundlanders want budget decisions to be set by “their democratically elected government” or “the privately elected executive of the NTA”?

Other public sector unions would join the fight against the Liberal government, some of their leaders running for the NDP under Jack Harris. These unions would fund attack ads against the government and directly contribute to local candidates — both NDP and PC.

Simms and Harris put the emphasis not on cuts but on growth, though Simms also promised to reduce Newfoundlanders’ already heavy tax burden.

The PCs went after Wells’s constitutional distractions, too. Simms said the premier “became so obsessed with the Constitution that it took all his time and that is one of the reasons this economy has gone the way it has.”

“Clyde Wells’s biggest problem in governing Newfoundland is that it takes so long to fly to Calgary, Toronto and Winnipeg!”

But Wells used his experience as a sword. He demanded more provincial control over the fisheries, which he argued the federal government had mismanaged. That would take a constitutional amendment — and who else had more experience on this file than Clyde Wells?

Nevertheless, a strong campaign by Simms, the constant attacks by labour groups and a full slate of candidates for the NDP was taking its toll on the Liberals. Their lead at the beginning of the year had been more than 40 points. A late-campaign poll put the margin at less than half that. A big improvement for the PCs, but not quite enough to put the outcome in doubt. The PCs even ran ads claiming “a vote for the NDP is a vote for Clyde Wells”, as they were concerned the New Democrats would siphon off too much of the anti-government vote.

Perhaps Simms and the unions made this into a race that would have been a walk had it not been for their efforts, but the results nevertheless gave Wells and the Liberals a bigger mandate than in 1989.

The party captured 35 seats, up four from the previous election, and increased its vote share by two points to 49.1%. The PCs, who had narrowly won the province wide vote in 1989, dropped 5.5 points to just 42.1%. With only 16 seats, the party had lost five.

Jack Harris succeeded in being re-elected in the riding he had secured in a byelection, but otherwise the NDP had little to show for their jump to 7.4%.

The Liberals had won another big majority in the first election to take place in the context of the severe budget cuts that were happening across Canada, an apparent endorsement of the tough love Wells had pitched to voters. But it might have simply been a recognition that Newfoundlanders had no better options. They had voted with their hearts in 1989. Now they had to vote with their heads.

1996 Newfoundland election

Brian Tobin storms Newfoundland

February 22, 1996

It was a whirlwind that brought Brian Tobin to the premier’s office in the first weeks of 1996.

Clyde Wells, the Liberal premier of Newfoundland since 1989, had announced his decision to resign in December 1995. It wasn’t long before his replacement came forward: Brian Tobin, the popular fisheries minister in Jean Chrétien’s federal government.

Tobin had made a name for himself with his leadership during the so-called Turbot War, when Canada faced-off with Spain over fishing rights off the Newfoundland coast. Tobin also played an important role in the 1995 Quebec referendum that put him on the national stage.

He announced in early January 1996 that he would leave federal politics to run for the provincial leadership. Seeing the writing on the wall, no one dared oppose Tobin and he was acclaimed as leader.

Newfoundland was in dire straits at the time, facing a collapsed fishery and very high unemployment. But Tobin saw signs of prosperity on the horizon, particularly in resource development.

Once sworn in, he re-appointed Wells’s cabinet and would have called an election right away if only the elections officials were ready. A new electoral map had been drawn up and the voter lists weren’t printed.

“We’re like the team that got strapped up and ready to go,” said Tobin, “and found out the guy who was supposed to grease the sleds had not done so.”

Telling reporters they could reconvene after the weekend, Tobin set his election date for Feb. 22, kicking off a 24-day campaign less than 72 hours after becoming the sixth premier of the province.

Tobin sought a mandate of his own, and the polls suggested he was very likely to get a big one with numbers in the 70s.

In the party’s platform, a red book like Chrétien’s in 1993 and titled “Ready for a Better Tomorrow”, Tobin called for the jobs and revenues that would be derived from mining and offshore oil drilling to stay in Newfoundland. The ore should be smelted in the province and the oil refined locally rather than being shipped out. Newfoundland would further diversify itself away from the collapsed cod stocks with fish farming, tourism and technology.

Against the Tobin juggernaut, the Progressive Conservatives had little to offer. Lynn Verge, a former cabinet minister in Brian Peckford’s government and leader of the PCs since 1995, argued that “Brian Tobin is trying to steamroller over people. He came through a short leadership contest unchallenged and then he calls a snap election, hoping people won’t have an opportunity to scrutinize his record.”

Verge’s campaign was not nearly as dynamic and lively as Tobin’s, and she tried to tie the former federal minister to some of the unpopular decisions being made by the Chrétien government. Changes to unemployment insurance and spending cuts would impact Atlantic Canadians especially hard, and the Chrétien Liberals would pay for those decisions in the 1997 federal election. But in Newfoundland in 1996, it was the Tobin Show.

There was an air of inevitability surrounding Tobin and the Liberals throughout the campaign, something Liberal candidates used to their advantage when they told voters it would be better to have a member on the governing side than on the opposition benches.

That there was only one party likely to form government even led Jack Harris, leader of the New Democrats, to go after Verge during the leaders’ debate as he vied for the few votes available for the other parties. Faced with the possibility of a Liberal sweep in its own polling, the Evening Telegram went so far as to endorse the election of at least some opposition members.

The unseasonably warm election day on February 22 resulted in a big Liberal victory, though not a sweep. The “message of hope, a message of confidence” that Tobin saw in the results sent 37 Liberals to the House of Assembly, two seats more than Wells had won in 1993 when there were four more ridings on the electoral map.

The Liberals took 55.1% of the vote, up six points from the last election. But it wasn’t all good news — a trio of cabinet ministers went down to defeat, in part due to the changes made to riding boundaries.

The PCs dropped from 16 to nine seats, taking just 38.7% of the vote. The party went from five seats to just one in western and central Newfoundland and lost their two seats on the Burin Peninsula. Only on the Avalon Peninsula did the opposition succeed in electing a sizeable opposition, with eight of 20 seats in the region.

Verge, however, was defeated in her own riding of Humber East, a seat she had held since 1979. She would resign the leadership shortly after the election.

The New Democrats, who only managed to run 20 candidates, succeeded in re-electing Harris. But he would remain the lone New Democrat in the House.

Also elected was Yvonne Jones, who ran as an Independent after losing the Liberal nomination to Danny Dumaresque in the Labrador seat of Cartwright–L’Anse-au-Clair. Though her pledge to join the Liberal caucus was initially rebuffed by Tobin on the campaign trail, she would be the Liberal candidate in 1999 (and a future party leader).

Tobin would have one more election victory to look forward to when he called a second early election in 1999. But he’d make the jump back to federal politics the following year — and the Liberals would not win the next time without him.

1999 Newfoundland election

N.L. Liberals win four in a row

February 9, 1999

As Newfoundland and Labrador entered the last year of the 1990s, the province had been governed by the Liberals for a decade. But its energetic premier, Brian Tobin, had only been in office since 1996, when he led the Liberals to a big victory after replacing fellow Liberal Clyde Wells in the top job.

Only three years into his own term, Tobin claimed he needed a new electoral mandate to back-up his negotiations with Quebec over Churchill Falls and his showdown with nickel company Inco over a mining project in Labrador. That made these two resource projects the focus of the short 23-day election campaign.

Against him, Tobin faced a rookie Progressive Conservative leader in Ed Byrne, while Jack Harris of the New Democrats would mount his third campaign as leader. Tobin waged a relentless, whirlwind campaign that was considered a foregone conclusion.

The pre-campaign polls were good for Tobin and the economy of Newfoundland and Labrador was humming along as the province topped the nation in economic growth. Oil revenues were flowing and the fisheries had a good year. Unemployment was still more than twice the national average at around 18%, but things were looking comparatively good in Newfoundland and Labrador.

So, Tobin won his expected victory, though the opportunistic call might have cost him a little. His Liberals captured 50% of the vote, down five points since 1996, and won 32 seats, five fewer than the last time.

The PCs picked up two percentage points, capturing 41% of the vote, while the NDP was up four points to 8%. But it was the PCs who gained the most in seats, up five to the NDP’s one, with PC gains coming in central Newfoundland and on the Avalon Peninsula.

Though the PCs were making progress, Byrne would eventually step aside and be replaced by businessman Danny Williams, who was acclaimed as leader and would be swept to power in 2003, after Tobin had taken his leave.

Like his win in 1999, a jump back into federal politics was widely expected for Tobin — it was actually seen as one of the reasons he decided to call an early election. Tobin was viewed as a potential replacement for Jean Chrétien as federal Liberal leader and thus prime minister, at least among those who wanted an alternative to Paul Martin.

Accordingly, Tobin cut his second term short and ran for federal office when Chrétien called an election in 2000. But, perhaps seeing Martin as unbeatable, Tobin eventually threw in the towel for good in 2002. Speculation would rise again when a new leadership race was called in 2006 to replace Martin, but Tobin would stay on the sidelines, never ascending to the higher office he was always thought to covet.

2001 Newfoundland Liberal leadership

The workhouse vs. the warhouse in Newfoundland & Labrador

February 3, 2001

In the first months of the 21st century, Brian Tobin and the Liberals seemed to be in a good spot in Newfoundland and Labrador. Tobin had led his party to another majority government in the election of 1999, marking a decade in power for his party. The Liberals took 32 seats in that vote, the Progressive Conservatives under Ed Byrne just 14.

But Ottawa had other plans.

Jean Chrétien, spying an opportunity to take advantage of an unsteady Canadian Alliance opposition under new leader Stockwell Day, called an early election for November 2000. Though Tobin had promised to see out his term in office in St. John’s, the siren song of federal politics was too much for him to ignore. The Liberals needed him to win back Atlantic Canada, where the party had suffered significant losses in 1997. And Chrétien needed an heir that wasn’t Paul Martin. Maybe Brian Tobin would be that man.

So, Tobin resigned. It was a move that shocked the province. Deputy premier Beaton Tulk was named to replace him while the Liberals searched for a new leader. They immediately had two candidates in Roger Grimes and John Efford.

Grimes, an MHA since 1989 for a riding on the north coast of Newfoundland, had been a cabinet minister in both Brian Tobin’s and Clyde Wells’s governments. He held tough portfolios like labour and education, but got through them without much difficulty. At the time of Tobin’s resignation, Grimes was heading up the health ministry — another challenging job.

Efford was also a veteran MHA and cabinet minister, first elected in 1985 in his riding on the Avalon Peninsula. Efford attracted more controversy in his ministries, including his strident and outspoken advocacy of the seal hunt and his defense of the fisheries against decisions made by the (Liberal) federal government. He was more charismatic and pugilistic than the mild-mannered Grimes, and a populist who, in the words of Michael MacDonald of the Toronto Star, was “often perceived as too colourful for his own good.”

A third candidate came forward in Paul Dicks, first elected in 1989 on the west coast of Newfoundland. Minister of mines and energy, Dicks had presided over deep spending cuts during his time as finance minister.

According to Kevin Cox, St. John’s correspondent for The Globe and Mail, “if Mr. Grimes is the workhouse and Mr. Efford is the warhorse, then Mr. Dicks is the dark horse.”

Nevertheless, though he had a “plodding speaking style”, Grimes was seen as the favourite as the convention approached. He had the backing of the establishment of the party and most of the caucus. Efford, on the other hand, had support among the grassroots membership. Dicks was a long shot, but if Grimes failed to win on the first ballot his supporters could decide the winner.

About 1,300 delegates braved a snow storm to attend the convention in Mount Pearl’s Glacier Arena on February 3, but their mood was grim. It wasn’t just the weather. On January 30, the Liberals had been defeated in two byelections held in traditionally safe Liberal strongholds. One of them was Tobin’s old seat.

The Progressive Conservatives were now on the upswing under their new leader, businessman Danny Williams (who would officially be acclaimed later in the year). The party was surging and Williams’s style seemed like a tough one for Grimes to stack up against — a fighter like Efford could have a better shot.

On the first ballot, Grimes emerged with the most support but was just short of a victory. He had 609 votes to 546 for Efford and 111 for Dicks, who crossed the convention floor to join Efford after he was eliminated. If Dicks could deliver 80% of his delegates, Efford would win.

Dicks nearly did it, as Efford gained 78 votes on the second ballot. But Grimes gained 29, just enough for him to finish with 638 to 624 for Efford. If eight more delegates had gone for Efford, he would have won.

Efford’s supporters booed when the results were announced. The party had been divided between the establishment and the grassroots. At first, Efford called for unity. In his victory speech, Grimes said “there's just one, great, strong, united Liberal party that can go forward with pride from today.”

The unity wasn’t real and it didn’t last. Within months, both Efford and Dicks would leave provincial politics rather than serve under Grimes. Efford followed Tobin to Ottawa, and served in Paul Martin’s cabinet.

Grimes struggled on as premier for the next two years, but his chances against Danny Williams were slim. When the next election was held in 2003, the Liberals went down to defeat with just 12 seats, the PCs winning 34. Worse, Williams and the PCs won the province wide vote by nearly 26 percentage points.

The long Liberal reign was over. The Danny Williams era was about to begin.

2014 Newfoundland and Labrador PC leadership

50%+1, and we really mean it

September 13, 2014

It had been over a decade since the Progressive Conservatives had come to power in Newfoundland and Labrador under the dynamo that was Danny Williams. But in 2014, Williams was gone and it was Kathy Dunderdale who had been piloting the ship of state since 2010.

Things had started well enough for the new premier when she won a landslide victory of her own in 2011, but by 2013 the PCs were deeply unpopular. There was internal dissent within the party (one MHA crossed the floor to the Liberals) and Newfoundlanders and Labradorians were growing tired of the Tories after they had brought in an austerity budget and reacted ham-handedly to a series of rolling blackouts.

Worse, the PCs were now down in the polls — by a lot. They were trailing the Liberals by more than 20 percentage points, and in January 2014 Dunderdale saw the writing on the wall and announced her resignation.

Thus started the first of two strange leadership races for the Newfoundland and Labrador Tories in 2014.

By April, Corner Brook businessman Frank Coleman was the only candidate still standing to replace Dunderdale as PC leader and he was acclaimed. But, just a few weeks before he was scheduled to be sworn-in as premier, Coleman announced he wouldn’t take the job after all, providing no more detail than that there was a serious medical issue in his family.

So, back to the drawing board.

When the next round of the leadership began, former St. John’s East MHA John Ottenheimer was in right from the start. He had been out of politics since 2007 but had been a cabinet minister in Williams’ government.

A few weeks later, Paul Davis, the MHA for Topsail since 2010 and minister of health, jumped into the race, saying the PCs needed “a new beginning.” The very next day, the list of contenders grew to three when Steve Kent, MHA for Mount Pearl North since 2007 and minister of municipal and intergovernmental affairs, threw his hat in the ring. Younger than the other two, Kent pitched himself as “something fresh.”

By the time voting day arrived on September 13, Davis appeared to be the front runner. He had nearly as many endorsements from the PC caucus as Ottenheimer and Kent combined. But excitement for the fresh or new start wasn’t entirely high — the PCs had lost some key byelections and were still trailing the opposition Liberals by more than 20 points.

But Davis was in for a surprise on the first ballot when Ottenheimer finished ahead of him with the support of just over 42% of the delegates gathered at the St. John’s Convention Centre. Davis finished with 37% support, while Kent was in third with just under 21%.

Eliminated after that first ballot, Kent endorsed Davis — though not all of his delegates were happy with the choice and more than a third would not follow Kent to Davis.

Still, it seemed like it would all come down to the second ballot. After all, only two candidates were on it. But conventions-goers were puzzled when officials announced that after the second round of voting, there had been “no clear majority”.

How could that be?

The count was incredibly close. Davis had 340 votes in his favour and Ottenheimer had 339. But one ballot had been spoiled — the delegate marked an X for both Ottenheimer and Davis — and party officials had to determine whether Davis’s one-ballot victory counted as receiving “more than 50 per cent of the valid ballots cast”.

The Davis camp protested, saying that Davis had the clear win. But John Noseworthy, the party’s chief electoral officer for the contest, ruled that Davis needed 50% plus one vote to prevail.

The math behind the decision was a bit confusing (and still is today), but a third ballot went ahead. Perhaps sensing that taking the victory away from Davis at this stage would do little good, a net 13 delegates either swung from Ottenheimer to Davis or didn’t vote. The result was that Davis won an undisputed but narrow majority on the third ballot, taking 351 votes to Ottenheimer’s 326.

It ended what was a bit of an odd year for the Newfoundland and Labrador Progressive Conservatives. But things would only get worse — by the end of 2014, Davis and the PCs were trailing the Liberals by 30 points and with just one year to go before facing voters. Things wouldn’t improve.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Newfoundland and Labrador and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Smallwood: The Unlikely Revolutionary, by Richard Gwyn

Frank Moores: The Time of His Life, by Janice Wells

No Punches Pulled: The Premiers Peckford, Wells and Tobin, by Bill Rowe

I think it’s interesting to note that the PC Party’s Chief Electoral Officer for the 2014 leadership race, John Noseworthy, was the previous Auditor General of Newfoundland & Labrador. Just a fun fact!