#EveryElectionProject: New Brunswick

Capsules on New Brunswick's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in New Brunswick.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1925 New Brunswick election

The province’s first Acadian premier goes down to defeat

August 10, 1925

New Brunswick’s economy was depressed, the government was indebted and unemployment in the province was high. But the previous election had been held five years ago. Like it or not, Premier Pierre-Jean Veniot had to send New Brunswickers to the polls in 1925.

Though parties weren’t officially recognized at the time, Veniot was a Liberal. He was also New Brunswick’s first Acadian premier, taking over from Walter Foster when he resigned in 1923.

On July 17, with the clock running out on the legislature, Veniot set the date for the next election: August 10, 1925.

The biggest issue in the campaign was the Liberal government’s huge hydro-electricity project at Grand Falls. Veniot had always intended on making this publicly-funded project the ballot box issue, stating in 1924 that “we feel the people should have a final voice in the matter before we undertake the real work of development.”

But Veniot grew impatient, and in 1925 his government got the ball rolling on the project, passing legislation that tripled New Brunswick’s borrowing power for the project to nearly $13 million — a huge sum for a province with an annual budget of just $4.1 million at the time.

The opposition cried foul on Veniot’s flip-flop. Shortly before the campaign began, the Conservatives chose John B.M. Baxter, federal MP for Saint John, to lead the party. He would, in the words of the Conservative-friendly Moncton Times, end “the orgy of extravagance” that had occurred under the Liberals.

Baxter charged that the Veniot government was not providing nearly enough details about the feasibility of the project, especially considering its gargantuan cost. The Liberals were rushing into it for no reason — why not wait until the election was over and the people had spoken?

“Are we going to stand,” wondered Conservative candidate Leonard P.D. Tilley, “for another $15,000,000 liability jumped upon us in the last moments of a dying Government? I think the people of this Province, both Liberal and Conservative, will cry, ‘Halt’.”

The Liberals countered that the Conservatives were in hock to the big interests of the lumber and paper industries that dominated New Brunswick. The depression had hit them hard and half of the province’s saw mills had closed. They wanted reduced power rates from the Grand Falls project, but the Liberals would not give them everything they wanted.

As the campaign unfolded, Liberal-leaning newspapers pushed the narrative that Veniot was fighting for the little guy against the heartless logger barons. On the stump, the premier deplored “the brazen attempts to steal away the people’s interest.”

A side issue in the Saint John area was the Liberal government’s introduction of the compulsory pasteurization of milk, a measure that would reduce deaths from tainted milk. The Conservatives, however, attacked the measure, wanting to make people free to purchase what they termed “pure milk” and pledging to “cut out all fads and fancies” in the Department of Health. The Liberals’ health minister defended the policy on the basis that it would save lives.

But something that might have had an even bigger impact on the results was the strain of anti-French bigotry in some quarters of anglophone New Brunswick. The Acadian, Catholic and French-speaking population in the province formed a big minority, but a minority nonetheless. The English Protestant majority in the south was not particularly receptive to the idea of an Acadian premier.

While Baxter himself didn’t attack Veniot’s heritage — he even attempted speaking French to audiences in the north — there was an undeniable “whispering campaign” that passed along the message that ‘a vote for Veniot is a vote for the Pope of Rome’. There were allegations that the Ku Klux Klan, which was an active player in Canadian elections in the 1920s, was involved in trying to influence voters as well.

As Arthur T. Doyle puts it:

“It was one of the great campaigns in New Brunswick’s stormy political history: the posters, the cartoons, the exhaustive canvassing, the countless meetings, the ginger ale and ice cream picnics, the rallies, the oratory, and the endless handshakings. The leaders took full advantage of the fashionable automobile and the modern highway network to criss-cross the province attending massive rallies. Probably no other two New Brunswick politicians had achieved so much exposure in a single campaign … In many small towns they attracted audiences of over 1,000, and in the cities, the crowds sometimes exceeded 2,000 … For the political parties, it was almost certainly the most expensive election ever. While the Liberals said the lumber companies financed the Conservative campaign, the Conservatives said the Grand Falls contractors financed the Liberals. They were probably both right.1

Turnout was strong on election day. After the votes were all cast crowds of hundreds gathered outside newspaper offices to await the results. As the numbers rolled in, they were announced over megaphone and written on blackboards in the windows of the offices.

The result was a big victory for John Baxter and the Conservatives, who won 37 seats — an increase of 24 since the 1920 election. The Liberals dropped 13 seats, winning only 11. The United Farmers (who had burst onto the scene in 1920) were wiped out, including the three who ran as supporters of the Liberal government in Carleton county.

While the debate over the Grand Falls project might have dominated the campaign, the map hinted at the linguistic divide that might have been just as decisive.

The only seats the Liberals won came in the counties of Madawaska, Victoria, Gloucester and Kent — areas with big French-speaking Acadian populations. The Conservatives swept the southern anglophone ridings, defeating incumbent Liberal MLAs in places like Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John.

Veniot held on as leader only until 1926, when he made a successful jump to federal politics with Mackenzie King’s Liberals.

Baxter’s Conservatives, meanwhile, would be re-elected in 1930 and the Grand Falls project would be completed in 1931 — after it was sold to a private company.

But, like many Great Depression-era governments, the Conservatives would be turfed in the subsequent election in 1935 by the Liberals under Allison Dysart, a leader who would inspire the political career of Louis Robichaud who, in 1960, became New Brunswick’s first Acadian premier with an electoral mandate of his own.

1932 New Brunswick Liberal leadership

Twice interim, Dysart made permanent leader of the NB Liberals

October 5, 1932

On a fall day in 1932, some 600 Liberals made their way to the Fredericton Opera House to attend their provincial party’s convention. At issue was who would lead the New Brunswick Liberals into the next election — and potentially back into power.

“The majority of the Liberal delegates arrived in the capital by auto,” reported the Fredericton Daily Mail, and “the convention which began shortly after two o’clock was one of the most enthusiastic ever held in this city.”

New Brunswick, like the rest of Canada, was in the grips of the Great Depression. The challenge had sparked rumours that the Liberals would enter into a coalition with the governing Conservatives. It was something those gathered at the convention strongly and clearly opposed.

The goal was to kick the Conservatives out of office, regaining what the Liberals had lost in 1925. At the convention, a wire from Mackenzie King was read to the delegates, in which the Liberal opposition leader in Ottawa called for a “Liberal united determination to win back New Brunswick.”

The choice for leader came down to two men. There was John B. McNair, a lawyer from Fredericton who had long been active in party circles. But the favourite was Allison Dysart, the party’s acting leader in the Legislative Assembly.

Dysart had sat in the assembly as the member for Kent since 1917 and had even been interim leader before. After the Liberals’ defeat in 1925, Dysart took over leadership duties after the resignation of Peter Veniot. But as the 1930 provincial election approached, the party urged Dysart to step side. He was a Catholic, after all, and Veniot’s Catholicism (and Acadian heritage) was blamed for the party’s defeat.

The change to a Protestant leader didn’t have the desired outcome, and the Liberals (as well as leader Wendell Jones in his own riding) were defeated in 1930. Leaderless on the opposition benches, Dysart took over the job once again.

This time, though, Liberal delegates were set on keeping Dysart in his post for good and, according to the Moncton Transcript, Dysart prevailed by 459 votes to 97 for McNair.

In his victory speech, Dysart “levelled a barrage of vituperation against the expenditures of the present [Conservative] government,” according to the Daily Mail. As a consolation prize, McNair was elected as president of the party.

An editorial in the Daily Mail welcomed Dysart’s victory.

“From east, west, north and south came sturdy delegates determined to square the account by restoring Mr. Dysart to the position from which he was cruelly ousted just prior to the election of 1930, lop away the mouldering branches and make some effort to restore the old party to the position, which it held in New Brunswick before it fell upon evil days, largely as the result of kindergarten leadership.”

Dysart would eventually lead the Liberals to a sweeping victory in 1935. Among those appointed to his cabinet would be John B. McNair, the new attorney general. While Dysart would only govern New Brunswick until 1940, McNair would step in and continue the Liberal run in power for another 12 years.

Little did those delegates know that the two men they chose from in 1932 would govern the province for most of the next two decades.

1944 New Brunswick election

McNair bucks the national trend

August 28, 1944

Mackenzie King’s Liberals were in some trouble in 1943 and 1944. The war was dragging on, conscription was dividing the country and people were looking ahead to change in a post-war order. Polls — a new addition to the political landscape in Canada — suggested support for the Liberals had dropped to the low-30s. The newly-christened Progressive Conservatives weren’t far behind, and nipping at their heels was the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation.

Provincial Liberal governments were dropping like flies. Ontario ushered in a PC government in 1943. Then the CCF came to power in Saskatchewan and the Union Nationale ousted the Liberals in Quebec in 1944.

Would John B. McNair’s Liberals in New Brunswick be next?

The 1944 election in New Brunswick would be McNair’s first as Liberal leader. He had taken over from Allison Dysart in 1940, shortly after Dysart had won re-election the year before. McNair had spent the next few years running a wartime government, delivering surplus after surplus.

But the King Liberals risked dragging down the New Brunswick wing of the party. So, when McNair dissolved the legislature and set the date for the next election for August 28, 1944, he endeavoured to make the campaign about provincial issues, not federal ones.

The PCs wouldn’t have it. Hugh Mackay, who was named leader after the party’s 1939 defeat, was a wealthy lumber baron who married into a New Brunswick political family. He hoped to capitalize on discontent with Mackenzie King’s Liberals, saying “it is quite impossible to discuss Provincial affairs and ignore Federal.”

The Liberals did their best anyway. McNair touted his government’s record, its investments in pensions and support for mothers, as well as the work done to pave the province’s roads and improve New Brunswick’s infrastructure.

A correspondent for The Globe and Mail provided national readers with a brief description of each of the leaders. McNair was “bright-eyed, alert, youthful, he is sometimes reserved and sometimes a glad-hander”, while “big, rugged, “Buff” Mackay is as much at home in the woods of his native Province as he is on St. James St[reet]”.

But it wasn’t just the two-party race New Brunswickers were used to. Running candidates across the province for the first time was the New Brunswick wing of the CCF, led by J.A. Mugridge, a “tall, tweedy man with a quiet drawl.” An electrician and trade unionist running in Saint John, Mugridge and the CCF faced some serious challenges in the province despite the party’s national surge in the polls. The CCF’s organization was still small, and Saint John’s newspapers refused to publish any of the party’s pre-campaign ads. Help from the central HQ of the CCF, including a visit by national leader M.J. Coldwell, gained the CCF some attention, but not much support.

Despite some worries in Liberal circles, in the end New Brunswickers gave McNair a renewed vote of confidence. The party picked up seven seats, including all four in York County where McNair put his name forward. He had been defeated in York County in 1939, but this time he was one of the top four finishers. (At the time, each county elected multiple MLAs.)

The PCs were reduced to 12 seats, all but three of them in and around Saint John. The other three came in Carleton County.

“The people of the province are evidently satisfied with the present government,” said Mackay in a post-election statement, “so all I can say is good luck to them.”

The CCF finished second in Madawaska County and had strong showings in Saint John and Moncton, but otherwise made few inroads. It was a fact that was noted in national media as the CCF was otherwise making progress in the polls and in provincial elections across the country.

Mackenzie King and the federal Liberals breathed a sigh of relief when the New Brunswick returns came in. They tried to spin the results as a signal that things were turning around for the party. And maybe they were. When King sent the country to the polls the following June, the Liberals suffered some losses but nevertheless held on to power — with the help of a few extra seats from New Brunswick.

1970 New Brunswick election

Louis Robichaud gives it one last try

October 26, 1970

Jean Lesage and the Quebec Liberals came to power in 1960, an event that marks the start of the Quiet Revolution that transformed the province. That same year, Louis Robichaud and the New Brunswick Liberals kicked off a revolution of their own.

Robichaud was the first Acadian premier in New Brunswick to win an electoral mandate of his own and over the next 10 years he would reform the province, giving the French-speaking Acadian minority more say in governance and greater equality with the English-speaking majority.

He would win re-election in 1963 and 1967. In his third term in office, he brought forward the Official Languages Act that would divide the province but eventually get passed unanimously in 1969.

It exhausted a government that was already running out of steam. Robichaud, too, was losing his enthusiasm for the job that he won when he was only 34 years old. He had hoped to step aside and hand the leadership over to someone else, but the delays in getting the Official Languages Act passed and a hoped-for judicial appointment from Ottawa that never came kept him in the premier’s chair.

By the end of the summer of 1970, Robichaud just wanted to get the next election done so that he could win it and pass the job over to someone else who could have time to reboot the Liberals. He had also called a couple of byelections that the Liberals risked losing — better to avoid those painful defeats, call a general election and hope to catch the Progressive Conservative opposition by surprise.

The PCs, though, were ready. Now under Richard Hatfield, just 39 and “a modern, liberal-minded Conservative”, according to a Southam News correspondent, Hatfield had his party’s platform out before even the Liberals did. The Liberals didn’t even get their platform out to the newspapers in time to fill the adspace the party had purchased — the blank news pages that resulted gave Hatfield something to point to as the Liberal platform.

Hatfield’s strategy was to argue that after a decade of bewildering reform, New Brunswickers needed a change of government that would calm things down and get the province’s finances back in order.

There were few major issues during the campaign, but two would have some electoral repercussions in Moncton. Anglophones in the city were hoping to send their children to bilingual schools in order for them to learn French, but Acadians were worried that it would only accelerate the assimilation of their community into the English-speaking majority.

The Robichaud government was also put on the backfoot by a proposal made by two British experts hired by the Liberals to recommend reforms to the healthcare system. The experts suggested amalgamating the two hospitals in Moncton into a single hospital, something that neither anglophones nor francophones supported and which made a mockery of the government’s on-going construction of a new French-language hospital.

These issues went by the wayside, though, when the kidnapping of James Cross and Pierre Laporte by the FLQ gripped the nation. The October Crisis distracted voters, heightened English-French tensions and took Robichaud out of the province when he attended Laporte’s funeral in Montreal. Robichaud also now found himself guarded by officers of the RCMP that kept him at a distance from voters, and one rally had to be cancelled when a bomb threat was called in.

Hatfield, though running a good campaign that included touring the province by helicopter and reaching out to Acadians in their own language (or, at least, attempting to), was still seen as the underdog when October 26, 1970 approached. Observers thought the election would be close but that Robichaud and the Liberals would eke out another win.

Instead, Robichaud was handed a narrow defeat as the province split along linguistic lines.

Reversing the results of the 1967 election, the PCs won 32 seats and the Liberals won 26 seats, with both parties capturing 48.5% of the vote. The Liberals, though, ran up bigger majorities in the francophone north than the PCs did in the anglophone south, and so found themselves behind by a few seats.

Only a handful changed colours. In 1970, New Brunswick still had ridings that elected multiple candidates and the PCs were able to gain all three of the seats in Moncton. They also picked up the seat in Edmundston, where Robichaud hadn’t cashiered a minister involved in scandal, and two in Sunbury, where the soldiers at Gagetown had been deployed to patrol the streets of Montreal.

With the exception of a single seat in both Queens and Saint John, the Liberals were pushed back to the northern and eastern edges of the province where Acadian francophones were the majority.

Robichaud, commenting on results, recognized that “the people decided they wanted a change”, while Hatfield said he would govern for all New Brunswickers, regardless of region or language. Robichaud would eventually get that call from Ottawa when he was made a senator in 1973, while Hatfield would continue to govern until the historic defeat of the PCs in 1987, when the party did not win a single seat.

1982 New Brunswick election

Richard Hatfield’s last majority

October 12, 1982

The 1978 election in New Brunswick was a near-death experience for premier Richard Hatfield and his Progressive Conservatives. In Hatfield’s attempt to win a third consecutive term in office for his scandal-plagued government, he was nearly toppled by Joseph Daigle and the Liberals. Only two seats separated the two parties.

The Parti Acadien, which advocated for the rights of New Brunswick’s French-speaking Acadians (and ultimately a separate province), emerged as a force in the election, taking 12% of the vote where it ran candidates and nearly electing one MLA.

Acadians had traditionally backed the New Brunswick Liberals, acting as a solid base for that party and a ceiling for the Progressive Conservatives. The PCs needed to win southern, anglophone New Brunswick in order to form government, while the Liberals could afford to only split the south.

But with the rise of the Parti Acadien signaling that the Liberals no longer had a monopoly on the Acadian electorate, Hatfield and his francophone lieutenant, Jean-Maurice Simard, spied an opportunity.

Hatfield’s government launched a charm offensive in the north, investing huge sums of money on infrastructure projects and new schools and hospitals, as well as creating autonomous French-speaking school districts and a bilingual public service, bringing in the controversial Bill 88 which recognized the equality of the two linguistic communities.

While welcomed by Acadians, these efforts did not go over particularly well with English-speakers in southern New Brunswick. Nor was Hatfield’s PC caucus entirely behind him.

But it also split the Liberals, as Daigle flip-flopped on Bill 88 and shook the confidence of his MLAs, who eventually voted by a margin of 23 to three to remove him as leader. His replacement was 41-year-old lawyer Douglas Young, who represented a riding in the north.

The Parti Acadien, too, faced its own internal divisions, such as what position it should take over Quebec’s 1980 referendum. The Hatfield PCs decided to take advantage of the divisions plaguing their opponents. They would conduct two entirely separate campaigns, one led by Hatfield in English in the south and the other led by Simard in French in the north.

When Hatfield officially began the campaign in early September 1982, he pledged to protect the province from the effects of the recession that was hurting the country. He would exercise restraint but would not cut services. At the outset, he enjoyed a small lead in the polls over the Liberals, despite New Brunswick’s difficult economic situation, high unemployment and struggling forest industry.

Though Young was also critical of his federal cousins, Hatfield tried to tie Young and the New Brunswick Liberals to prime minister Pierre Trudeau, who was unpopular at the time. He also reminded voters of the role — exaggerated or otherwise — Young played in engineering Daigle’s downfall. Such disloyal ambition could not be trusted in the premier’s office.

In the north, Simard took a different tack, emphasizing the steps the PCs had already taken to empower the Acadian population and promising to implement much of the platform that had been the Parti Acadien’s.

The dual nature of the campaign proved divisive within the PC Party, but it proved effective among the electorate — who largely existed in two distinct media and political ecosystems.

It was a campaign dominated by pricey promises from the PCs and Liberals, including such measures as mortgage assistance, help for small businesses, job creation programs and universal kindergarten. What’s more, the platforms put forward by the PCs and Liberals were similar, making it difficult for voters to draw a distinction between the two.

They weren’t the only parties in the field. The Parti Acadien ran a reduced number of candidates in the north. The New Democrats, now under school teacher George Little, ran a more professional campaign than they had in 1978, with nearly a full slate of candidates and help from organizers with experience electing the NDP in British Columbia.

The campaign was considered a close one heading into election day, but the result was the biggest majority Hatfield would ever win.

The Progressive Conservatives won 39 seats, flipping a number of seats from red to blue in areas with significant Acadian populations. The PCs were up nine seats from the 1978 election, gaining three percentage points to finish with 47.4% of the vote.

The Liberals lost a lot of ground in northern New Brunswick as well as a few seats in the south, dropping 10 seats to just 18 and three points to 41.3% of the vote.

The New Democrats successfully won Tantramar, where they had finished a close second in 1978. Little was defeated in his own riding, but he did lead the NDP to their first seat victory ever.

Support for the Parti Acadien collapsed to just 0.9% and no candidate placed better than third. It would be the last election contested by the party.

Michael Harris, writing in The Globe and Mail, took a dim view of the campaign that had unfolded:

“For much of the campaign Mr. Hatfield and Mr. Young traded insults. The Premier accused Mr. Young of being disloyal to Mr. Daigle in leading the caucus revolt that ousted the former Liberal leader; Mr. Young characterized Mr. Hatfield as the head of a corrupt administration in bed with the federal Liberals. In the cut and thrust of what was often a nasty exchange, Mr. Hatfield emerged the clear winner.”

But Hatfield couldn’t keep up his high-wire act forever. Scandals continued to plague his government and the divisions he fostered in the 1982 campaign eventually ripped the PCs apart. In the 1987 election, Hatfield would finally go to defeat when Frank McKenna and the Liberals won a clean sweep of all 58 of New Brunswick’s ridings.

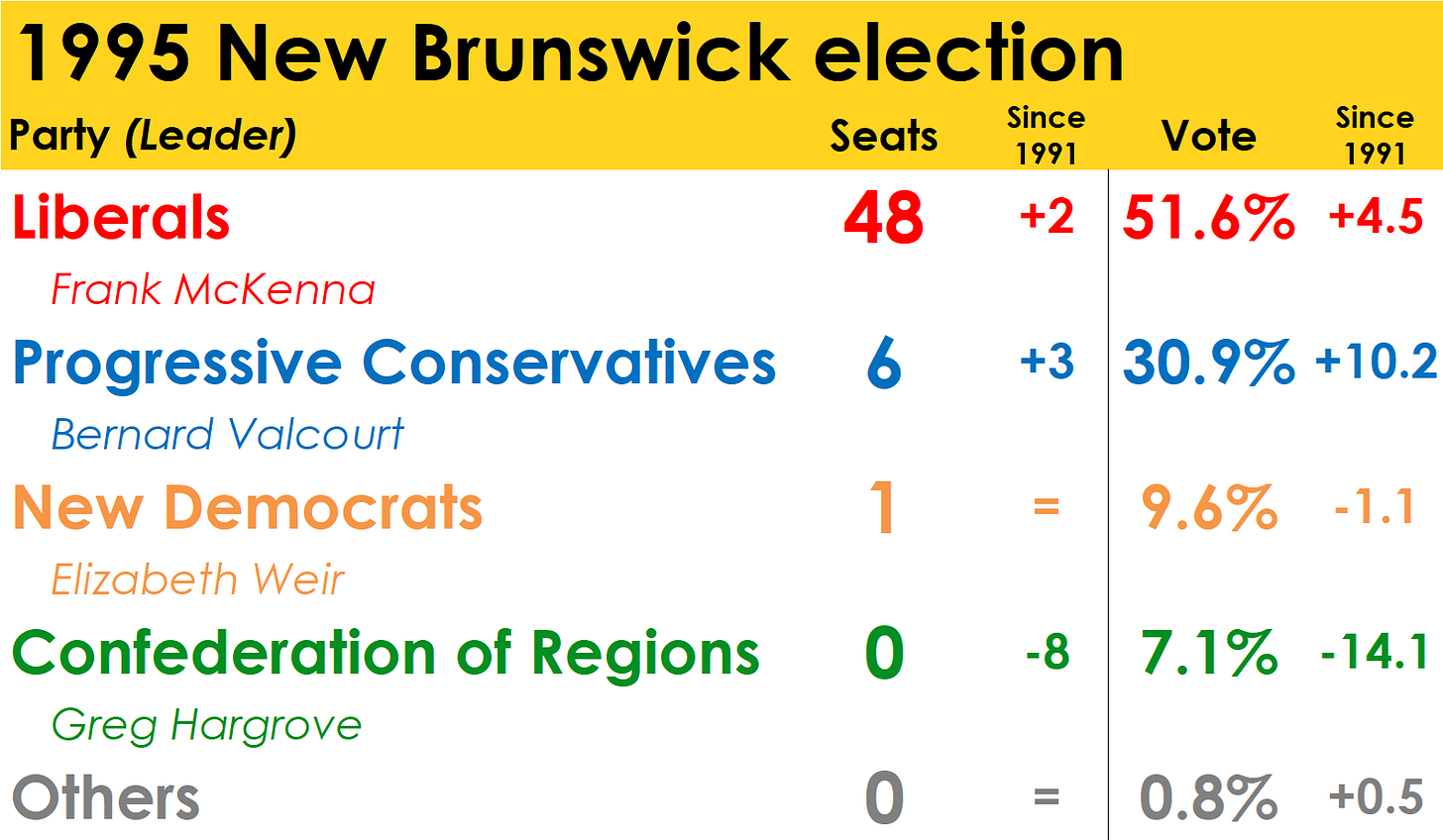

1995 New Brunswick election

McKenna wins again as PCs re-emerge from wilderness

September 11, 1995

It seemed that New Brunswick politics was heading in a new direction after the 1991 election. Frank McKenna’s Liberals had won another big victory — not as big as when they won every seat in 1987 — but the second-place party was not their traditional foes, the Progressive Conservatives. Instead, it was the Confederation of Regions Party that formed the official opposition with eight seats and 21% of the vote.

COR grew out of anger over New Brunswick’s bilingualism policies. Some unilingual anglophones felt that they were being excluded from job opportunities to placate the province’s francophone Acadians, and so elevated the grassroots, populist COR past the Tories, who were still reeling from the shattering 1987 defeat of then-premier Richard Hatfield.

But, somewhat inevitably, COR spent the years after its 1991 breakthrough in a downward spiral. Its membership believed in the role of the grassroots, and chafed at attempts by party leader Danny Cameron to provide top-down direction. Eventually, tensions between the party membership, the party’s executive, its caucus and its leader reached a boiling point and Cameron’s leadership was put to a review. He lost it and was replaced by firebrand Brent Taylor, who in turn was rejected by the COR’s caucus, who did not recognize him as their leader in the legislature.

The turmoil didn’t end there. Taylor was removed as leader by the party’s executive and Cameron ran the show until he quit for good and was replaced by Gary Ewart, who himself resigned after a few weeks when he couldn’t establish control over the party and the caucus. The interim leadership went to MLA Greg Hargrove, but the damage had long been done. Infighting within the party, as well as its inability to make good on any of their anti-bilingualism policies — equality between the two linguistic communities was enshrined in the constitution on COR’s watch — had whittled down their support to single-digits.

It provided an opportunity for the resurgence of the Progressive Conservatives. Under Dennis Cochrane, the party was doing a better job of providing an opposition in the legislature than the disorganized, bickering COR crew were able to do. The PCs were able to win back some of the voters they had lost to COR and moved into second place in the polls.

But as the 1995 election approached, Cochrane resigned the leadership and was replaced by Bernard Valcourt, a former cabinet minister in Brian Mulroney’s government. He was a pugnacious politician and tried to open the door to former COR members and MLAs, saying they could be part of his team if they adhered to the PC platform. A francophone New Brunswicker, he had the credibility to make an outreach like that to former COR supporters that might have alienated Acadians had an anglophone like Cochrane attempted it.

But the PCs were still trying to rebuild from their shellacking over the previous two elections. They had little money and the party organization was still in a rougher shape than that of the Liberals. Valcourt’s appeal in his home region around Edmundston was strong, but he was a harder sell in the south. His own advisors suggested he be kept out of the party’s few English-language advertisements.

Frank McKenna, by comparison, was looking golden. His party had been able to attract support from COR voters who had moved on from the bilingualism issue and saw in the Liberal premier a fiscal conservative they could swallow a lot easier than Valcourt.

Since 1987, the Liberals had been running an effective government — cutting spending and balancing budgets but also increasing job growth in New Brunswick. The provincial Liberals were a well-funded, well-organized and well-oiled machine that would have been a formidable opponent even if its rivals weren’t so weak. Before the writ dropped, some pundits were saying that another 1987-style sweep wasn’t out of the question for McKenna.

The memories of Richard Hatfield were partly to blame. His term in office had ended with personal scandal and tumult. It wasn’t hard to do better than that. Even Hargrove recognized this, saying “you know, Richard, after he left and McKenna went in, all he had to do was go to work at eight in the morning and he’s a hero.”

No one doubted that the Liberals would win another big majority. The Liberals didn’t sweep, however, instead winning 48 of 55 seats (the legislature had been reduced from 58). The Liberals took 52% of the vote, up 4.5 points from 1991, winning every seat in Fredericton and Moncton and taking rural districts across both anglophone and francophone New Brunswick — including every seat that had been won by the Confederation of Regions in their breakthrough campaign.

The PCs won three seats in Madawaska County, including Valcourt’s in Edmundston, and another in the Acadian Peninsula. They won two other seats in anglophone ridings, including one just outside of Saint John. That city also re-elected Elizabeth Weir, the leader of the NDP. Her party was competitive in only one other riding — the one next door to hers.

While COR still held on to 7% of the vote, they lost all of their seats and finished (a distant) second in only two ridings. The party was over. It would fall to less than 1% of the vote in the next election and then disappear altogether.

The unbeatable Liberals? They’d be fine as long as Frank McKenna was at the helm. But he wouldn’t stay forever.

1997 New Brunswick Progressive Conservative leadership

Bernard Lord bridges the divide

October 18, 1997

It had been a tough 10 years for the New Brunswick PCs.

The nightmare started in 1987, when Richard Hatfield’s Tories were swept out of every riding in the province by Frank McKenna’s Liberals. Over the next few years, their support was further gutted by the rise of the anti-bilingualism Confederation of Regions party, which managed to finish second in the 1991 election. As the COR started to fall apart, the PCs picked up some of the pieces. But in 1995, now under the leadership of former Conservative MP Bernard Valcourt, the PCs were only able to regain semi-respectability with six seats and official opposition status once again.

The PCs had expected they would be able to regain more of the support they had lost to the COR. Valcourt, a francophone Acadian, didn’t seem to have much appeal in the anglophone south, where the PCs captured just two seats. Valcourt managed only a little over 60% in the leadership vote that followed his defeat and he resigned, excoriating some of the PC caucus members who didn’t support him along the way.

The party was at a crossroads. Hatfield had brought them to power by bridging the divide between francophones and anglophones. But the results of the 1987 election and the rise of COR in 1991 demonstrated how that had come at a great price. Some elements in the party felt that the PCs needed to be led by an anglophone again to have any shot at rebuilding. Others felt they needed someone who could appeal to both communities without alienating either one.

Whoever would win the leadership would be up against a big challenge. McKenna’s Liberals seemed invincible and over the preceding decade the PCs had been a party riven with internal divisions. The slate of candidates who emerged reflected the job’s limited appeal.

There was Cleveland Allaby, a lawyer from Fredericton who had failed to win a seat for the PCs in the 1997 federal election. Margaret-Ann Blaney, a Newfoundlander and another failed former federal candidate, also put her name forward.

The two frontrunners, though, took very different approaches to the leadership contest.

Norm Betts was a business professor at the University of New Brunswick. His campaign kept its focus on a first ballot victory, making little effort to reach out to his opponents.

And there was Bernard Lord. He was 31 when he launched his bid and turned 32 just a few weeks before the contest came to a close. Lord had very limited political experience, having lost his own bid to win a seat in the 1995 provincial election. But he had something that no other candidate had — something that made him seem like the ideal candidate to lead a party like the New Brunswick PCs.

In a province still divided by language, Lord was able to pass between the two communities with ease. His father was an anglophone New Brunswicker who married a French-speaking Québécoise from the Lac-Saint-Jean region. Lord grew up in bilingual Moncton and learned to speak French and English without an accent. In the anglophone south, Lord could pass as an English New Brunswicker. In the francophone north, he could pass as an Acadian (even if he was actually half-Québécois). Neither side of the linguistic divide would have to compromise.

His youth, too, could be seen as an asset. Louis Robichaud, Richard Hatfield and Frank McKenna all became premiers before the age of 40. Clearly, New Brunswickers weren’t averse to electing young premiers.

While Betts focused on his campaign, Lord reached out to the others. It would pay off on the convention floor.

The main event was held in the Aitken Centre in Fredericton and four other satellite voting locations were organized across the province. For Betts, the strategy was to win it on the first ballot on the strength of his anglophone base in the south. For Lord, the strategy was to get the race to multiple ballots, in hope that his campaign could roll up the votes going to Allaby and Blaney.

On that first ballot, it was clear which strategy was going to be the winning one. Lord emerged on top with 36.6% of the 3,800 ballots cast, with Betts finishing a close second with 32.2%. Allaby and Blaney were well behind at 17.4% and 13.9%, respectively.

Finishing last, Blaney was eliminated. Allaby could have stayed on, but he decided to withdraw after seeing how far behind he had placed. At this point, both Blaney and Allaby went over to Lord’s camp, the three candidates standing on chairs in front of the stage to show convention-goers that the three were united.

The number of votes in the second round dropped by about 600, but of those that did stick around for that second ballot it was Lord who won the lion’s share of Allaby’s and Blaney’s vote. His total jumped by 440, Betts by 190, a margin of roughly two-to-one. Lord’s ability to build consensus — an important skill in New Brunswick politics — had helped him win victory.

It still seemed like a return to government was a distant prospect. The Liberals had won eight times as many seats as the PCs in the previous election. But the Tories had a leader with real potential to replicate Hatfield’s winning formula and, two years later, Lord would lead the PCs to their biggest electoral victory — ever.

1999 New Brunswick election

The bell tolls for the New Brunswick Liberals

June 7, 1999

You can’t go anywhere but down after a perfect sweep.

That’s what happened to the New Brunswick Liberals in the 1987 election when the party went 58-for-58, ousting (and humiliating) Richard Hatfield’s PCs.

Under Frank McKenna, the Liberals lost a few seats in 1991 and held their own in 1995. But by 1999, McKenna was gone and the Liberals had been in power for more than a decade.

It was up to Camille Thériault, McKenna’s replacement as party leader and premier, to keep the Liberals afloat. The polls augured well for his party, so Thériault set the date for his first test with voters for June 7, 1999.

But Thériault was not exactly a household name in New Brunswick. Despite being in McKenna’s cabinet, the former premier was not one for sharing the spotlight. It levelled the playing field somewhat for the new leader of the Progressive Conservatives, a young lawyer from Moncton named Bernard Lord.

Perfectly bilingual and equally at ease among anglophones and francophones, Lord was trying to have the party move on from the divisive debate over bilingualism. It had contributed to Hatfield’s collapse in 1987 and the rise of the anti-bilingualism Confederation of Regions to official opposition status in 1991. The grassroots, populist outfit couldn’t keep itself together, though, and by 1995 it had fallen back significantly in popularity.

By 1999 it was a spent force, and Lord went about bringing former COR supporters back into the fold. His stance for official bilingualism in New Brunswick with an emphasis on “fairness and justice” made both Acadians and COR voters feel at home in Lord’s PC Party.

While there were some grumblings within PC ranks over welcoming the COR elements that had abandoned the party, the Liberals made a misstep when they tried to make an issue of it. It was an attempt to shore-up their own francophone base as well as to divide the PCs in two, but their efforts received some blowback from a population that had grown tired of division over language.

A bigger problem for the Liberals, though, might have been a highway toll.

During McKenna’s tenure, the Liberals had signed a contract with a private company to build a much-needed highway between Moncton and Fredericton. News that it would be a tolled highway outraged locals. Lord promised to re-negotiate the contract and get rid of the tolls, but Thériault refused to budge and his campaign events would be greeted by angry protestors.

The issue fit perfectly with Lord’s overall focus on the bane of high taxes under the Liberal government. Thériault tried to make the campaign instead about the economy and health care, and criticized the PC plan to scrap the tolls and cut personal income taxes as fiscally irresponsible.

There were some weaknesses in the Liberal strategy, though. Thériault wouldn’t explicitly distance himself from his predecessor, but he tried to present a more compassionate approach than the one under McKenna, which included austerity measures that closed schools — much resented in the Acadian Peninsula — and cuts to hospital beds.

The Liberals might have also gotten complacent and lazy. Robert Pichette, an Acadian columnist writing in the Globe and Mail, said the Liberal campaign’s “slogans are as trite as their posters are amateurish; in fact, their entire campaign so far looks as if it were devised by rank amateurs.”

When mid-campaign polls suggested the Liberal walk had turned into a competitive race, suddenly Bernard Lord and the PCs looked like a legitimate alternative to voters who had previously been concerned with making sure their MLA was sitting on the government benches. Accordingly, the Liberals and Thériault sharpened their attacks against Lord — perhaps too little, too late, and the attacks also reinforced the PCs’ standing as a potential government.

Expectations were that it would still be pretty close. Instead, the PCs won a huge majority of 44 seats with 53% of the vote, a gain of 38 seats and 22 points since the previous election in 1995.

And it wasn’t just the southern English-speaking parts of New Brunswick that backed the Tories. The PCs gained five seats in northern New Brunswick and swept the eight seats in the Moncton area, in addition to sweeping Fredericton, gaining five seats in and around Miramichi and 10 more in the south.

The seats along the toll highway? They all went PC.

“Our province has voted for change,” Lord told the cheering crowd at his victory rally. “Today New Brunswickers forged a new beginning for a new century.”

The Liberals were reduced to just 37% of the vote, winning seven seats in the francophone regions in the north and east and a few more in the west.

The New Democrats under Elizabeth Weir retained her seat of Saint John Harbour, but otherwise the NDP was only competitive in two other ridings across the province. The Confederation of Regions all but disappeared, failing to register even 5% support in any riding in New Brunswick.

For the next few election cycles, New Brunswick’s political map would not be so riven by linguistic divides as it had been before. But the re-alignment achieved first by Hatfield and then by Lord would be short-lived. Not much more than a decade after Lord’s 1999 breakthrough, New Brunswick would revert to its Liberal-north and Tory-south divide — and another party critical of official bilingualism, the People’s Alliance, would re-emerge. It, too, would be re-integrated into the Progressive Conservatives, though without the same linguistic sensitivity as under Bernard Lord.

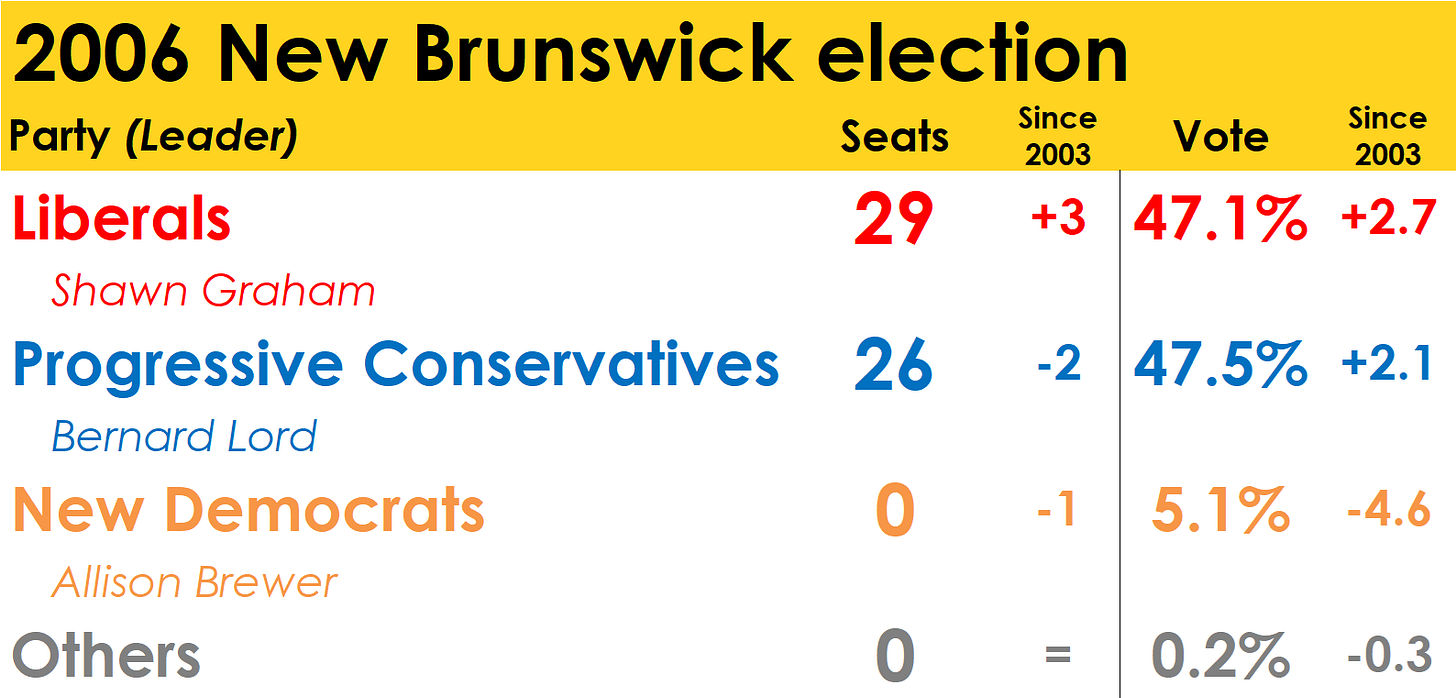

2006 New Brunswick election

Bernard Lord’s career ends early

September 18, 2006

Once upon a time, the next great leader of the Conservative Party was going to be Bernard Lord. His name was routinely thrown about as a potential contender for the party leadership. Maybe he’d run against Stephen Harper in 2003. Maybe he’d run to replace Stephen Harper when he eventually stepped down.

Lord had all the ingredients for a successful federal run. He was young. He was bilingual. He was moderate. He was a winner. He had taken the New Brunswick Progressive Conservatives from a state of shambles back to power and seemed destined to repeat his provincial success at the federal level.

It didn’t quite turn out that way. Lord’s string of success nearly came to a screeching halt when he eked out a majority of one seat in the 2003 provincial election. His opportunity to run federally came and went shortly thereafter when he did not put his name forward to lead the newly-merged Conservatives. He had a shaky legislative majority to worry about.

The PCs’ razor-thin majority became even thinner after the 2003 vote, which had produced 28 PCs, 26 Liberals and one New Democrat. When Elizabeth Weir, the leader of the NDP since 1988, resigned her Saint John seat, the Liberals picked it up. Both the PCs and Liberals lost MLAs who sat as Independents, depriving Lord of his majority. It was an untenable situation, and when one of Lord’s MLAs informed the premier that he would be stepping down to take a job in the private sector, Lord pulled the plug on his government. Otherwise, he’d risk losing the subsequent byelection and his plurality in the legislature.

Plus, the polls were looking better.

Lord’s main opponent in the campaign was the same person who had given him a scare in 2003. Shawn Graham, another young leader in a province that has liked young premiers, had done surprisingly well when he led his Liberals to near-victory.

The New Democrats had always been a party of one under Weir. When she went, so did the NDP’s only seat in the legislature. Allison Brewer took over the leadership of the seatless party and settled on a Fredericton riding as her hope for a win. She’d even get some help during the campaign with visits from federal leader Jack Layton and former federal leader Alexa McDonough. It wouldn’t do much good.

The campaign was instead a two-horse race — and two similar horses at that. Brewer quipped that Graham and Lord would save money if they just campaigned in the same bus. The two parties’ platforms were similar and their positions on the most-pressing issues were similar. The two leaders were even of a similar age. Lord complained that Graham had stolen much of his platform, calling it a “Shawny come lately” situation.

Five debates, three in English and two in French, did not settle matters, with no clear winner seen across them. But they served to emphasise the two-party contest, as the unilingual Brewer was excluded from the French language debates.

The campaign was seen as a late-summer, sleepy affair. There wasn’t much that differentiated the two main parties from each other and nothing emerged as the ballot box issue. It was a tight contest between change and continuation — and not much else.

The result reflected the lack of a decisive issue or a stark difference between the options on offer. Once again, only a few seats and a few votes separated the two parties — but this time the Liberals came out on top.

Graham secured 29 seats for his party, a gain of three over the 2003 election. The PCs dropped two seats and won 26, with the New Democrats being shutout. (They’d fail to finish second in any riding.) But while the Liberals won three more seats, they won less of the popular vote: 47.1% to 47.5% for the Tories. The Liberals, with gains in the urban centres of Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John to compensate for the losses of a couple of rural ridings in the anglophone south, had a slightly more efficient vote on a new map that was marginally favourable to the party.

It was by the thinnest of margins, but the Liberals had put an end to Bernard Lord’s impressive political career. Graham’s government would prove to be the first in what would be a string of one-term governments in a province that had been notorious for its electoral stability. Lord’s name would continue to be bandied about as a potential candidate for the federal Conservatives, but, after 2006, the once Great Right Hope would stay on the sidelines for good.

2010 New Brunswick election

New Brunswick’s first one-and-done government

September 27, 2010

When Shawn Graham’s Liberals narrowly defeated Bernard Lord’s Progressive Conservatives in the 2006 New Brunswick election, they came into office aiming to be just as transformative for the province as the earlier Liberal governments of Louis Robichaud and Frank McKenna.

Their agenda was ambitious — but that ambition very quickly became seen as recklessness. The Liberals attempted to reform post-secondary education and eliminate early French immersion, were taken to court over the restructuring of New Brunswick’s health system and they tried to cut some ferry services. These were projects that were floated and opposed and usually abandoned.

But New Brunswick needed some boldness. The provincial budget was in a deficit approaching $1 billion and the debt had grown to nearly $8 billion. One of New Brunswick’s troubled entities was NB Power, the electricity utility, and so Graham came up with a novel idea: why not sell it to Quebec?

It wasn’t long after Graham and Quebec premier Jean Charest announced the plan to sell most of NB Power to Hydro-Québec before a very vocal and widespread opposition to the notion made itself known. The government’s own polling suggested the idea was a big loser.

The credibility of the Liberal government had been shot through, and the plan was kiboshed. While the Liberals’ polling numbers improved after Graham backtracked, New Brunswickers had grown tired and untrusting of the government and its young, energetic leader.

After Lord’s defeat, the Progressive Conservatives selected David Alward, one of Lord’s cabinet ministers, as their new leader. Unflashy though he was, his relative dullness appealed to voters who wanted some peace and tranquility after the tumultuous Graham years.

When the 2010 campaign kicked off, the Liberals held a narrow lead in the polls over the PCs. It was going to be a tight affair, and neither party wanted to own-up to New Brunswickers about the dire straits the province’s economy was in. The towering debt and deficit would have to be dealt with post-election in one way or the other, but neither the Liberals now the PCs came forward with a solid plan about what they would do. Instead, the two parties made upwards of 600 promises, many of them costly, including a free laptop for all students (Liberals) or a power-rate freeze (PCs). When asked, both Alward and Graham would duck and dodge any question about whether they would cut spending or raise taxes.

The Liberals and PCs weren’t the only parties in the field. The New Democrats, without a seat in the legislature since losing their only holding in a 2005 byelection, were under the leadership of Roger Duguay, a priest from northern New Brunswick that gave the party more credibility among Acadians than it had had for a long time.

But the NDP, despite its limited electoral success, was a relatively ‘old’ party compared to two other new entrants. The 2010 election marked the first foray into provincial elections for the New Brunswick Greens, under the leadership of (former Liberal) Jack MacDougall. On the right, a new populist outfit that grew out of the grassroots opposition to the Liberal government also ran a small slate of candidates. It was the People’s Alliance of New Brunswick, under Kris Austin. Despite the lack of a seat in the legislature at dissolution, the leaders of the NDP, Greens and People’s Alliance were invited to the debates — reducing the focus on the fight between Alward and Graham.

Graham tried to ask New Brunswickers for another chance, saying in one of the debates that “when you have to lead you have to make difficult decisions. I know I'm not perfect. We've learned a lot and we can and will do better."

But voters appeared ready to do something they had never done before in New Brunswick’s history since the adoption of partisan politics in 1935: defeat a one-term government. By the campaign’s end, the PCs held a significant lead in the polls.

The results were even worse than the Liberals had feared. The PCs stormed to a big majority government, winning 42 seats and taking 48.8% of the vote. Their share of the vote had jumped by only 1.3 points since 2006, but the Liberals’ slide gave the PCs a big advantage.

Graham’s party lost 16 seats, falling to just 13 and 34.5% of the vote, down 12.7 points. Up to then, that was the lowest share of the vote the New Brunswick Liberals had ever received in an election.

The Liberals lost all their seats in Fredericton and Saint John and, with the exception of Charlotte-The Isles in the southwest, were limited to seats in Moncton and on the eastern shore of the province.

It was the rise in support for the NDP (10.4%, up 5.3 points) and the new vote won by the Greens (4.5%) that sapped the Liberals’ chances, particularly in Fredericton and Saint John. The PC vote didn’t increase much in those two cities, but the loss of Liberal support put the PCs ahead. In the rest of rural, anglophone New Brunswick, however, the PC vote surged.

The NDP did not win a seat, though they put up strong campaigns in two Saint John ridings and in the northeast, where Duguay came up just 1,300 votes short of winning his Tracadie-Sheila riding. The Greens had some respectable showings in the southeast and in Fredericton but were shutout — as was the People’s Alliance, which finished no better than third in just two ridings. Austin, however, took about 20% of the vote in his own riding. The Greens and People’s Alliance would have a role to play in New Brunswick’s politics, but not just yet.

Graham became the first New Brunswick premier to lead his party to victory in one election and go down to defeat in the next. But he wouldn’t be the last. The prize that David Alward won was not so glittering, and New Brunswick’s problems would soon make Alward the second New Brunswick premier to get just one term in office.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections New Brunswick and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Front Benches and Back Rooms, by Arthur T. Doyle

Louis Robichaud: La révolution acadienne, by Michel Cormier

The Right Fight: Bernard Lord and the Conservative Dilemma, by Jacques Poitras

Richard Hatfield: The Seventeen Year Saga, by Richard Starr