#EveryElectionProject: Manitoba

Capsules on Manitoba's provincial elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about the elections in Manitoba.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1878 Manitoba election

Canada’s first Indigenous premier

December 18, 1878

In 2023, Wab Kinew became the first First Nations premier of a Canadian province. He wasn’t the first Indigenous premier, however. That title belongs to another Manitoban: John Norquay.

(The Manitoba legislature has passed a bill to recognize Louis Riel as the first honourary premier of Manitoba, though he didn’t hold that title in an official capacity when Manitoba became a province.)

Norquay, an English-speaking Métis, became premier in October 1878 after the resignation of Robert Davis. Though Norquay at first faced off against Davis as leader of the opposition, he was brought into the Davis government as a cabinet minister. When he replaced him for the top job, Norquay became not only the first Indigenous premier in Canadian history, but the first Manitoba premier to actually be born in the province.

Though Norquay had some loose ties to John A. Macdonald and the national Conservative Party, partisan politics hadn’t quite yet taken root in Manitoba. In place of partisanship there was factionalism, largely based on race and language. There were the French, the English and the old settlers, “many of whom,” as described by G.A. Friesen in Manitoba Premiers of the 19th and 20th Centuries, “were of mixed [Indigenous] and European fur trade descent and others the descendants of Lord Selkirk’s 1812 Settlement”. Balancing the interests of the various factions was paramount in a province that was quickly changing — transforming from a place where those who spoke English and French were roughly balanced and where the Métis constituted a large portion of the population, into one that looked more and more like Ontario — white, English-speaking and Protestant.

As an English-speaker, Norquay was a good bridge between some of these groups. But he primarily derived his support from the French-speaking and “old settler” factions.

The election of 1878, called shortly after Norquay became premier, was a very local affair. There were only around 8,700 eligible voters, though that was nearly double the voting population of the previous election in 1874. It meant that local names and loyalties mattered most, but as the province grew, debates about how best to develop Manitoba’s economy became a part of political campaigning in the province as well.

Officially non-partisan, Norquay and his government supporters were broadly seen as Conservatives up against a Liberal opposition — not a bad association to have in an election held a few months after Macdonald’s Conservatives returned to power in Ottawa, sweeping Manitoba in the process.

Norquay, along with many of his supporters, were re-elected in the 1878 provincial election. Norquay won in St. Andrews South, taking 69 votes to 58 for his opponent. The election was a victory for the incumbent government, partisan or otherwise. His supporters held a majority in the small 24-seat legislature and Norquay would remain in his post until 1887.

1896 Manitoba election

Thomas Greenway sends a message to Ottawa

January 15, 1896

Elections in the late 19th century in Canada were often decided over the things that defined the country’s divisions at the time: language and religion.

This was the case of the Manitoba provincial election of 1896.

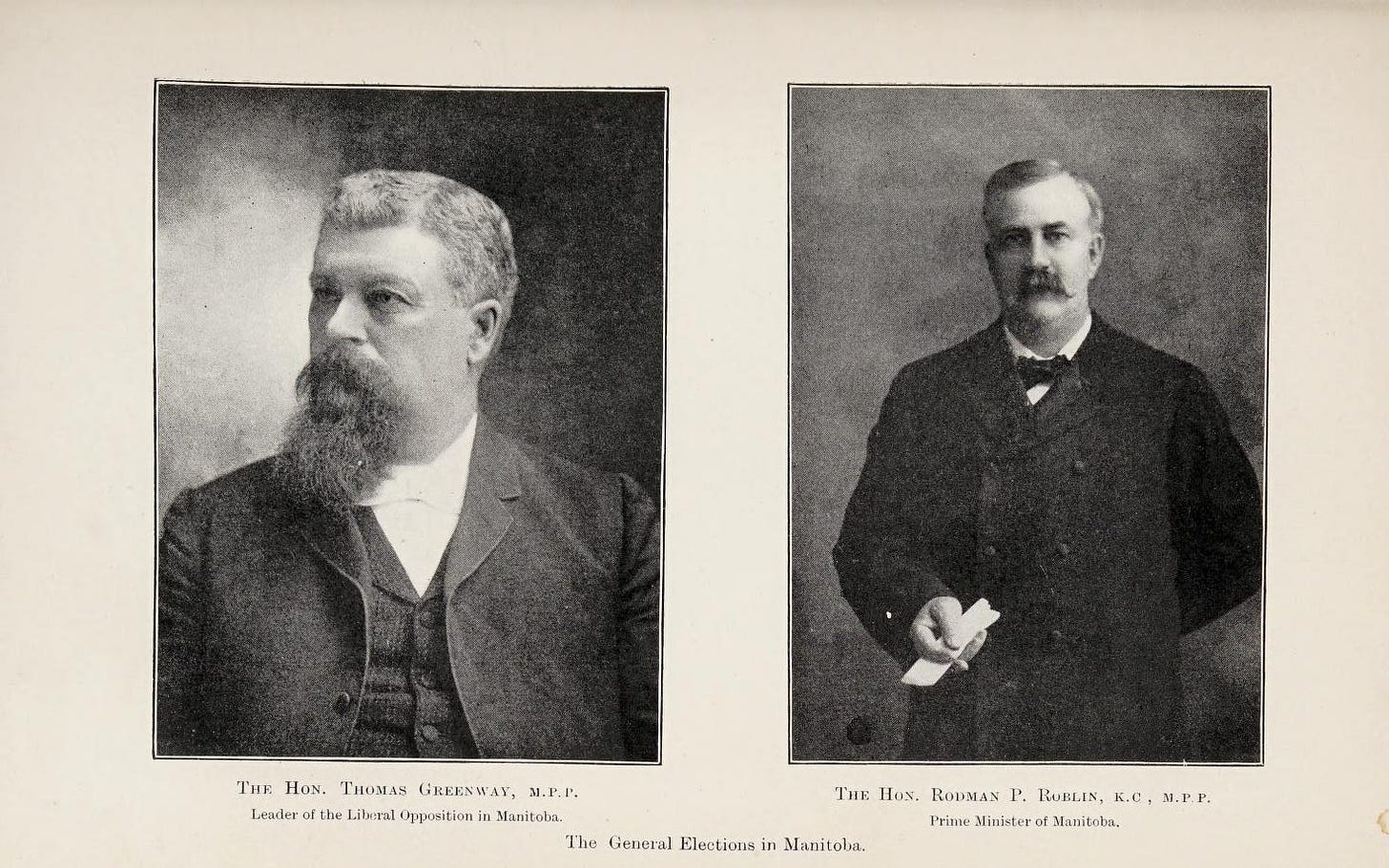

Since 1888, the province had been governed by Thomas Greenway and his Liberals. The Conservatives were a defeated and depleted force in the legislature. Instead, Greenway’s chief opponents — or political punching bags — were the Conservatives in Ottawa.

Upon joining Confederation in 1870, Manitoba had two separate, publicly-funded school systems: one was Catholic and predominantly French, while the other was Protestant and English.

That made sense in 1870, but by the late 1880s the population of Manitoba was overwhelming English-speaking, thanks in large part to an influx of Ontarians who wanted Manitoba to be a lot more like Ontario.

Knowing a popular policy when he saw one, in 1890 Greenway abolished the separate school system and made the French language no longer an official language of government. The new non-sectarian (though still Christian) school system would effectively get rid of French-language education in Manitoba.

There was pressure on John A. Macdonald’s federal government to disallow the legislation, as Macdonald still counted on support from francophones in Quebec. Instead, Macdonald decided to let this issue be decided by the courts — and it went through the various stages of appeals for a few years.

But by the mid-1890s, a ruling came down saying that it was up to the federal government to act. The Conservatives, now under Mackenzie Bowell, dragged their feat until introducing remedial legislation (which split the party in two and eventually contributed to Bowell’s fall).

This was great news for Greenway, who needed an issue to focus a re-election campaign around. He refused to follow the remedial legislation and Bowell gave Greenway six months to figure out a solution. The Manitoba premier took that time to prepare for a campaign, and dissolved the legislature on December 20, 1895, setting an election for January 15, 1896.

Greenway denounced the “menacing attitude assumed by the Dominion Government” as an attack on provincial autonomy and went on the hustings with little to fear from the local opposition.

The 1896 Manitoba election was a one-issue election. The combination of a popular policy (minority rights weren’t exactly vote-getters) and an anti-Ottawa campaign delivered a big landslide to Greenway’s Liberals.

His party won 32 seats (nine of them by acclamation) and 50% of the vote, leaving just five seats and 40% to the Conservatives, two seats to the Patrons of Industry (a farmers’ group) and one Independent.

Political affiliations were fluid at the time, but this represented a gain of five seats for the governing party since the 1892 election.

Despite the rebuke from voters, Bowell still pressed ahead to find a way out. But Greenway and the federal Liberals did everything they could to delay action until a federal election would be forced later in the year.

That 1896 federal election, fought over the Manitoba Schools Question outside of the province (inside, the provincial election had decided things), brought Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals to power. Shortly thereafter, Laurier and Greenway settled on a compromise which allowed some Catholic and French-language education where numbers warranted. The question wasn’t entirely settled for Manitoba’s francophones, who continued to fight for their rights, but it would no longer be the political football that it was in the 1890s.

1903 Manitoba election

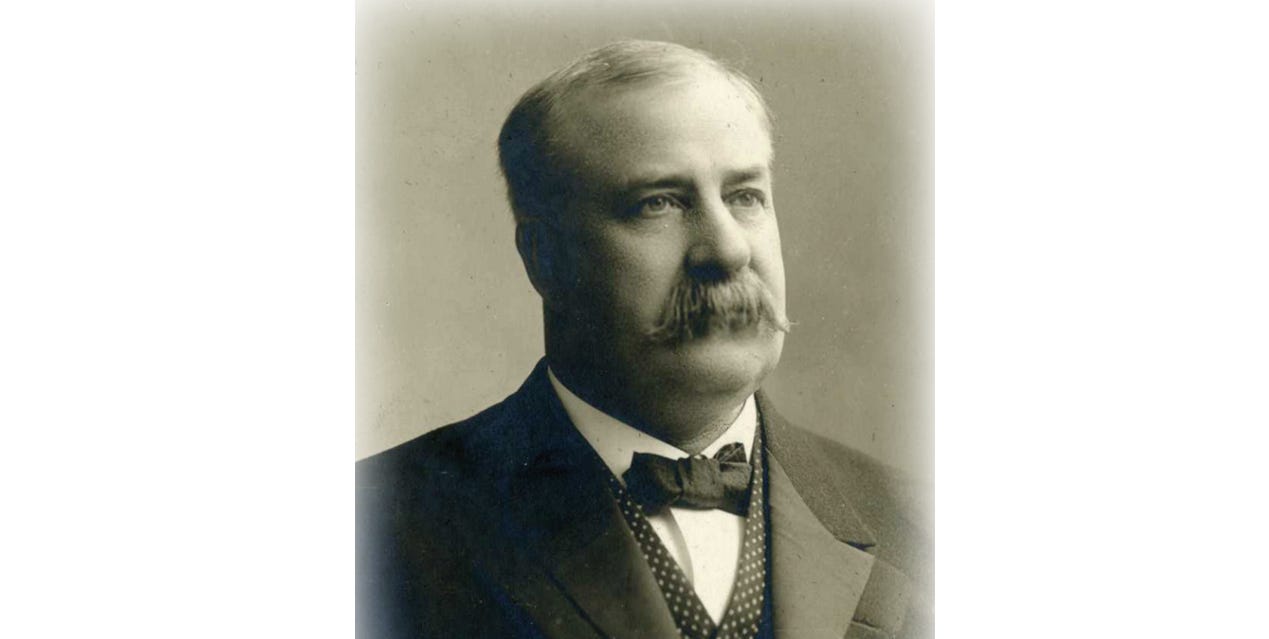

Rodmond Roblin is re-elected

July 20, 1903

Manitoba’s first election in the 20th century confirmed the province’s swing to Conservative politics — and the still potent power of patronage.

When the province went to the polls in 1903, Rodmond Roblin was a familiar face in Manitoba politics. He had been first elected as a Liberal in 1888 but had broken with the party over the government’s railway and French-language policies, and was promptly given the leadership of the opposition Conservatives. Roblin would hold that job until 1899, when he decided to step aside to make room for a political celebrity.

That celebrity was Hugh John Macdonald, son of the late former prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald. The son led the Manitoba Conservatives to victory in an election that year, narrowly beating out Thomas Greenway and the Liberals.

Macdonald, though, didn’t stick around for long — the siren song of the Dominion politics that had made his father famous came calling. So, Roblin stepped up again to take Macdonald’s place and became premier in 1900.

He navigated his first years in the job well, dealing with the controversial issue of prohibition by putting it to a referendum, which failed to pass, and by making significant progress on railway development in Manitoba. By building railways that provided competition to the dominant Canadian Pacific Railway, Roblin was able to provide relief to Manitoba’s farmers when the CPR was forced to lower its freight rates to stay in business.

Combined with new taxes that targeted corporations and railways, this solidified the farmer voters for the Roblin Conservatives. When Roblin sent the province (or, at least, its male residents) to the polls on July 20, 1903, at stake was not only his fledgling government, but the only Conservative government in the country at the time.

“A fluent speaker, and decidedly picturesque in his expressions,” according to The Globe, Roblin spoke at 10 meetings in two weeks, defending the government’s record and taking the fight to the opposition Liberals.

The Manitoba Liberals in 1903 were still led by Greenway, who had run the party for more than two decades and had served as premier from 1888 to 1899. A clever, opportunistic politician driven by expediency rather than ideology, Greenway had won his last victory in the Manitoba election of 1896.

At the time, Greenway had gone to war with the Conservative government in Ottawa over the issue of separate schools in Manitoba. It was a hot issue enflamed by the religious, linguistic and (to use the term of the time) racial divides separating French and English that defined Canada’s turn-of-the-century politics.

The wedge issue got Greenway re-elected in 1896, but when he settled it with the new Liberal government under Wilfrid Laurier, Greenway had robbed himself of an election-winner. After he lost in 1899, he also lost interest in provincial politics, hoping instead to land a cushy federal post. Though he was offered a Senate seat by Laurier, he was persuaded to stay in Winnipeg to keep the Manitoba Liberal Party together. He had a few good first years in opposition before problems with his own personal health and finances made him lose his focus and enthusiasm for the work.

Still, knowing that Roblin’s government was popular, Greenway tried to undermine it’s achievements with charges of corruption. He was helped in this by the Liberal-friendly Free Press, whose editor, John Dafoe, was charged with libel and arrested when his newspaper made allegations against the Conservatives.

These allegations surrounded a public works project that had started under the previous Liberal government. It was charged that the Conservatives demanded payments to the party from the person the Liberals had awarded the contract to, otherwise invoices would not get paid.

In a political move that is just as common in the 21st century as it was in 1903, Roblin turned the attack on the Liberals, denying the allegations and instead charging them of corruption, claiming the Greenway government gave out contracts to friends for work that was never done.

This sort of political patronage was common in Canadian politics at the time, and Roblin’s Conservatives were among the best at it. Their finely-tuned patronage machine would ensure that Roblin would stay in power for years to come. The charges of corruption didn’t stick this time, or at least they didn’t make the Conservatives look any worse than the Liberals.

“Election day opened with rain,” wrote a correspondent in Winnipeg for The Globe, “but it was not heavy enough to make the country roads too heavy for residents at outlying polls to get to their booths. In this city the vote was very heavy, a full half polled before the noon hour.”

The result was a big Conservative victory. Including votes for Independent Conservative and Liberal-Conservative candidates, who ran under that affiliation in ridings where the Conservatives didn’t have a candidate under their banner, Roblin took 50.6% of ballots cast and won 31 seats. It was a gain of just 0.8 percentage points but this produced eight seat gains over Hugh John Macdonald’s 1899 performance.

The Liberals dropped eight seats and nearly five percentage points, winning nine seats and 44.6% of the vote. Independent candidates, who included Labour and Prohibitionists, increased their share by four points to 4.8%, but did not elect anyone.

The Conservatives won in most of the rural regions as well as all three of the ridings in Winnipeg. The Liberals took only four seats around Winnipeg, three in the west of the province and two in the south, including Greenway’s seat. Roblin, for his part, won his Dufferin riding with the biggest margin of any candidate.

According to The Telegram, Roblin won because “the Government has been businesslike in its administration, and has brought the financial affairs of the Province into splendid condition and, even more important, it has shown itself to be progressive and energetic in the public interest and has grappled with great problems, such as that of transportation, not only fearlessly but successfully.”

After the election, Greenway finally made the jump to federal politics when he ran and won for the Laurier Liberals in the 1904 federal election. Roblin would remain as premier until 1915, when the years of patronage finally caught up to him and his party. He faced charges of corruption (of which he would eventually be acquitted when the jury was split), but the stink of patronage politics stuck to the Manitoba Conservatives. After Roblin’s departure, Manitoba shifted to the rule of anti-patronage Progressives. The Conservatives wouldn’t form government again in the province until 1958.

1910 Manitoba election

Rodmond Roblin and the joys (and risks) of patronage

July 11, 1910

Rodmond Roblin had been premier of Manitoba for a decade by 1910. Turn-of-the-century Canada was a good time to be in power. It made it much easier to stay in power.

The Conservative administration under Roblin had done a lot to build up the infrastructure of the young province. And building infrastructure — roads, railways and the like — meant giving out lots of contracts and government jobs. The Conservatives were good at doing that, too.

Winning elections when you have have all the power of patronage isn’t that difficult, and Roblin had secured a third consecutive victory for the Conservatives in 1907, defeating Liberal leader Edward Brown in the process. Brown even went down to defeat in his own riding.

The Manitoba Conservatives had a strong base in the rural areas of the province. But its farmers were becoming increasingly politically active. The Grain Growers Association, which would eventually evolve into the Progressive and United Farmer parties that would come to power in several provinces after the First World War, had lots of sway. The Grain Growers objected to the monopolies that private grain companies enjoyed, and they lobbied the Roblin government to setup publicly-owned grain elevators in order to undercut those companies.

Though the provincial government was limited in what it could do due to federal (or Dominion, as it was then called) jurisdiction, Roblin set something up for the farmers as a way to keep them on board. He also introduced some labour-friendly legislation regarding workmen’s compensation to shore up the Conservatives’ support in Winnipeg.

Roblin couldn’t take his re-election for granted because the Liberals were finally starting to get their act together. At a convention in early 1910, Tobias C. Norris, a farmer, auctioneer and MLA for a rural riding in the southwestern corner of Manitoba, was acclaimed as Brown’s replacement. Norris had already been doing the work in the legislature as House leader, and his skills in the auction house translated nicely to politics. He was a compelling speaker with a sense of humour, and the farmers had come to know him from the auction circuit.

Spying an opportunity, the Liberals under Norris began cultivating various populist and reformist elements who were opposed to the Roblin Conservatives — such as the temperance movement, women suffragettes and those opposed to the province’s contentious bilingual education system.

But Norris had a few disadvantages. Roblin wasn’t going to give him time to get comfortable as leader, and Norris was also being dragged down by the Liberal government in Ottawa. Wilfrid Laurier, now prime minister for 14 years, wasn’t very popular in Manitoba anymore. After winning 10 seats in the province in 1904, the Laurier Liberals were reduced to just two in 1908. One of the sticking points was the government’s feet-dragging on extending Manitoba’s borders northwards to the same latitude that had been awarded to Saskatchewan and Alberta when they became provinces in 1905.

Roblin knew a good election issue when he saw one. When he kicked off the 1910 election campaign in Carman and began his own tour of the province, he hammered home the boundary issue as the one voters should punish the Liberals over. That wasn’t all he had, though, as he could boast of the publicly-owned telephone system, the grain elevators and his party’s record of surpluses and spending.

The Conservatives tried to tie Norris to Laurier as much as possible. Robert Rogers, one of the leaders in Roblin’s government, charged that “there is a strong army of paid officials of the Dominion Government going up and down this country trying to defeat the will of the people.”

Norris countered that a Liberal government in Manitoba would settle the boundary issue quickly with their Liberal counterparts in Ottawa. And for every charge of Dominion corruption, the Liberals matched it with a corruption charge against the Conservatives. They also managed to secure the sought-after endorsement of the influential Grain Growers’ Guide.

The campaign, as was often the case in this era, could get feisty. Roblin’s Liberal opponent in his riding of Dufferin, W.F. Osborne, repeatedly accused Roblin of various corrupt acts. In one of their joint meetings, Osborne claimed that Roblin approached him on the platform and said “Osborne, you’ve got to cut out these personalities or I’ll skin you alive and make you eat mud.”

Roblin strenuously denied making the threats.

Despite the lively campaign, the results were much the same as they had been in 1907. The Conservatives won 28 seats and 50.8% of the vote, nearly matching exactly what they had accomplished three years ago. The Liberals won 13 seats (again), but saw their vote share drop by about four points to 44.2%. Still, Norris and the Liberals were satisfied with the progress they had made in Winnipeg.

Though the overall seat numbers didn’t change, a quarter of ridings did change hands: the Conservatives picked up five from the Liberals and the Liberals picked up five from the Conservatives.

It was a big victory for the Roblin Conservatives, and they’d have one more in them in 1914. But by then the charges of corruption were starting to stack up and stick to Roblin, particularly when accusations came out that the government had been less than clean in its awarding of contracts to build a new Legislature. Roblin was forced to resign and the lieutenant-governor turned to T.C. Norris to take over as premier.

He’d shortly thereafter secure a majority of his own in 1915 — and, not forgetting the reformists who joined him in 1910, made Manitoba the first province in Canada to give women the right to vote.

Rodmond Roblin’s last ride

July 10, 1914

Manitoba grew tremendously under the leadership of premier Rodmond Roblin. He took up the post in 1900 and, a year later, the census pegged Manitoba’s population at just over 255,000. After Roblin’s Conservatives had been re-elected a third time in 1910, the population of the province had nearly doubled to 461,000.

By 1914, however, Roblin’s grip on the province was growing weaker and the tolerance for the old ways of doing things was waning. Few governments of the day were squeaky clean and Roblin’s government was no exception. His Conservatives weren’t afraid to use public money and public servants for partisan purposes. And, of course, there was an expectation that hefty donations to party coffers would be made by those getting government contracts. Inflating invoices to cover those donations was common practice.

Increasingly, however, voters were tiring of this normalized corruption. They weren’t quite ready to back new parties — it would take the trauma of the First World War to shake voters out of their old habits for good — but they were starting to expect more from their leaders.

The opposition Liberals, reinvigorated under Tobias Norris, vigorously attacked the government’s corruption. A former auctioneer and compelling speaker, Norris had successfully gathered around him opposition elements in the 1910 election — prohibitionists, suffragettes and farmers — and, at a well-attended convention in early 1914, former leader Edward Brown predicted that a Liberal victory was just around the corner and that “the death-throes of the Roblin régime will be spectacular in the extreme”.

In June (in what would prove to be less than two weeks prior to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the event that would spark the outbreak of war in Europe), Roblin dropped the writ on the next provincial election, setting election day for July 10, 1914, nearly four years to the day since his last victory.

According to the Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, “this contest, which had been going on in some degree for months, was not a satisfactory or pleasant one; as in the case of all Canadian Governments, when in power for many years, there were varied charges of corruption and bitter personalities. Sir Rodmond Roblin, who for 14 years had been Prime Minister was not, at the best, a conciliatory opponent or a courteous fighter; his party enemies accepted the guage [sic] with true Western heartiness and the conflict was almost picturesque in the vehemence displayed.”

The Liberals took aim at the Roblin government’s corruption and presented a few platform priorities of their own: “direct legislation” (referendums) to get the support of the influential Grain Growers’ Association, prohibition, English-language compulsory public schooling and a vote on giving women the vote.

“To me it seems that the most serious problem which our people must face and must decide on July 10th,” Norris wrote in his party’s manifesto, “is whether or not domination of public affairs by machine rule shall continue. The Roblin Government, by reason of its long term in office, has become surrounded by an organized gang of political workers who have grown bold in their manipulation of matters pertaining to elections and patronage. As electors I ask you the plain question. How long do you propose to stand for rule by this machine?”

Education, as ever the case in turn-of-the-century Manitoba politics, was a flashpoint in this campaign. Amendments brought in by education minister G.R. Coldwell, designed to make it easier for the government to takeover Catholic schools, were criticized as opening up the doors again to publicly-funded separate schools — a charge especially taken up by the Protestant Orange Order. The government denied this was the case, but the Liberals hammered away at the issue. Norris even claimed that Roblin had personally invited him to support a return of separate schools, which Roblin denied ever happened.

The Conservatives had to run on their record, and it wasn’t a bad one. The province’s infrastructure had been built up over the preceding years, a new Agricultural College (now part of the University of Manitoba) had been founded and Manitoba’s territory had been extended to Hudson’s Bay. The government had also begun construction on a new legislature building that “would be an honour and a credit to the Province”.

“We come with a policy,” he said, “we come with a record, we come with a faith and hope born of conviction that there is a great future for this Province.”

Roblin took his message across Manitoba and over 20 days made stops in Carman, Miami, Stonewall, Emerson, Dominion City, Transcona, Portage la Prairie, Reston, Souris, Brandon, Ste. Rose, Dauphin, Grand View, Swan River, Gladstone, Birtle, Morden and Roland. He wasn’t alone on the hustings, getting assistance from “Dominion” Conservatives, including the Manitoba caucus and future prime minister Arthur Meighen.

In Transcona, Roblin pilloried the “direct legislation” movement as counter to the British tradition and said “I am strongly opposed to the ‘Banish the Bar’ plank as well as Woman’s Suffrage as I look upon them as unworkable fads and not in accord with the best interests of the people.”

Liberal leader Norris also criss-crossed the province, with visits to Ste. Rose, Roblin, Russell, Roseburn, Minnedosa, Elkhorn, Transcona, Winnipeg, Macgregor, Carberry, St. Pierre, St. James, Oakville, Portage la Prairie, Selkirk, Brandon, Boissevain and Rivers.

These two men weren’t the only figures garnering attention on the campaign trail. Nellie McClung toured Manitoba as well, advocating for woman’s suffrage and prohibition and against the Roblin Conservatives. She closed her campaign by addressing a crowd of 5,000 in Winnipeg on the eve of election day.

“I could not sit down when there was a fight like this on in my Province,” she said at one of her events. “I could not be contented with just doing ordinary little things – punching holes in linen and then sewing them up again … Too many men have one set of virtues for private life and another for public use. That is one reason why I hope to see a rebuke administered to the Government.”

Charges of corruption and vote-buying were made by both the Conservatives and the Liberals against each other, but in the end the Roblin Machine managed one more victory.

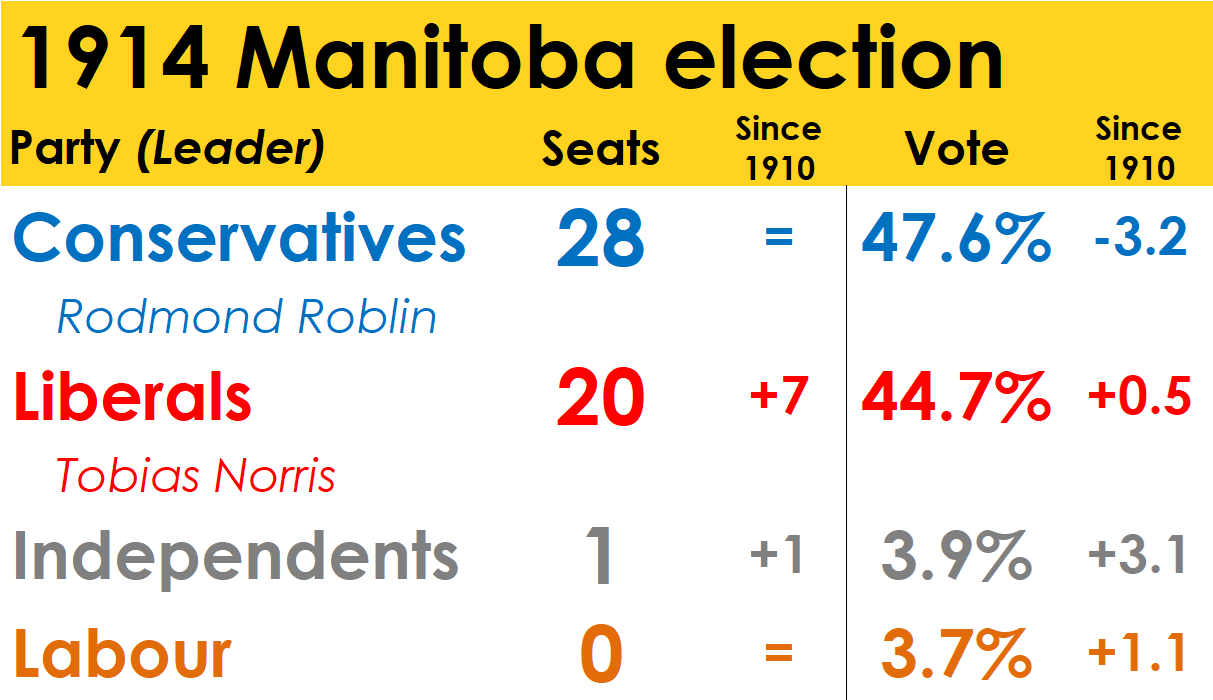

(As voters in Winnipeg received two votes to elect two MLAs for each of the city’s three ridings, the chart above shows the ‘equalized’ vote share for each party, as calculated by Elections Manitoba, which counts each vote in Winnipeg as half of one vote.)

The Conservatives saw their majority reduced in an expanded legislature, but nevertheless won 28 seats and just under 48% of the vote. That was a drop in vote share from the previous election, but enough to hold on. The Liberals increased their holdings from 13 to 20 seats and scored 45% of the vote, while one Independent (Fred Dixon, endorsed by both the Liberals and Labour) was elected in Winnipeg.

There was a divide between Winnipeg and the rest of the province — outside of the capital, the Conservatives and Liberals nearly split the vote evenly, 50% to 48%. In Winnipeg, Independent (often Socialists) and Labour candidates managed around 21% of the vote, with the Conservatives winning the plurality with 43%.

Stung by his reduced majority, Roblin blamed the result on the Orange Order’s baseless fearmongering on separate schools. McClung, meanwhile, took a moral victory out of the result.

“We have fought a good fight and we will keep on fighting; nothing can stop us; no man, not even Sir Rodmond Roblin, can hold his foot against the door much longer,” she said. “The machine is broken, the people will rule, and when we say people we mean both men and women.”

She wouldn’t have to wait long for the end of the Roblin government (or for women’s suffrage). Evidence of corruption in the awarding of contracts for the legislative buildings led to Roblin’s resignation less than a year later. In 1915, the Conservatives would finally go down to defeat at the hands of Norris’s Liberals. But that appetite for something different, for something unlike the politics of before, would take a bite out of the Liberals before long, too.

1919 Manitoba Conservative leadership

R.G. Willis becomes Manitoba Conservative leader

November 6, 1919

Politics were in flux after the dislocations caused by the First World War. In Manitoba, the Conservatives had been ousted from office in 1915 despite the presence of Robert Borden’s Union (read: Conservative) government in Ottawa. The Manitoba Tories had been taken down by scandal and corruption, and were being supplanted by organized farmers’ movements.

When the party called a convention to name a new leader in 1919, the Liberals were solidly ensconced in power and the direction the Conservatives would take was still in question. Though a handful of candidates were nominated at the convention held in the Royal Alexandra Hotel in Winnipeg, including Albert Préfontaine, who was leading the Conservative caucus in the legislature, and Agnes Munro (called “Mrs. James Munro” in the newspapers), only two let their names stand for the party’s leadership.

The favourite seemed to be Fawcett Taylor. Born in Manitoba and a former mayor of Portage la Prairie, Taylor had served in the trenches in France and returned home intact and with the rank of major.

His opponent was Richard Gardiner Willis. Born in Ontario, like many others he had made his way to Manitoba in search of better opportunities. By 1919, he had served as mayor of the small town of Boissevain in Manitoba’s southwest, and was dubbed a “well-known farmer” in the Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs.

The “well-attended” convention included five delegates for each of Manitoba’s 49 ridings, along with other non-voting participants. When the votes were counted, Willis emerged as the winner — though by how much was not announced.

His win was seen as a demonstration of the growing strength of organized farmers’ movements in the Prairies. Willis himself seemed to recognize this, saying he had “no doubt that Manitoba’s next Legislature will comprise a great many more farmers than it does at present. There are only seven at present, and I confidently expect that this number will be more than doubled.”

“They may be Conservative, Liberal or Independent Farmers, but they will be farmers first of all.”

According to the Canadian Press, “much enthusiasm was shown and victory at the next election was confidently predicted.”

Those predictions proved optimistic. Not only would Willis lose his own bid to win a seat in the provincial election in 1920, the Conservatives would finish fourth in the legislature — behind the Liberals, Farmers and Labour.

But Willis was on to something. Tobias Norris’s short last term would end in 1922 and the United Farmers of Manitoba, soon to be styled the Progressives, would form a majority government that year. The Conservatives would finish third but, this time, Willis (now just a candidate as the leadership had passed to Taylor) would win himself a seat on the opposition benches — in a legislature full of farmers.

1949 Manitoba election

Coalitionists re-elected

November 10, 1949

There’s been a lot of talk about coalitions lately (originally written on Nov. 10, 2021), as the Liberals and New Democrats have apparently been discussing (informally, they say) some sort of co-operation that could make this minority parliament last. But co-operation is not coalition — if there aren’t NDP cabinet ministers or MPs on the governing benches, it ain’t a coalition.

But coalitions used to be all the rage, at least when wars were raging. After the outbreak of the Second World War, a coalition government was formed in Manitoba that included all parties — the Liberal Progressives, Conservatives, Social Credit and the CCF. But by the 1949 election, only the Liberal Progressives and the Progressive Conservatives (as they were called by then) were still together, as Social Credit had dissolved away and the CCF had left the coalition before the end of the war.

The Liberal Progressives, themselves the result of an alliance between the old Liberal and Progressive parties, were led by Douglas Campbell, who had replaced Stuart Garson as premier when he made the jump to federal politics in 1948. The PCs were under deputy premier Errick Willis. Against them was the CCF under the leadership of Edwin Hansford, mounting his first (and only) campaign as leader.

It was a lopsided affair for the coalition. Campbell’s Liberal Progressives won 38% of the vote, with the PCs taking 12%. With the addition of a few coalition-aligned independent candidates, the total take for the governing side was 57% of the vote and 45 seats, with the Liberal Progressives accounting for 30 of them and the PCs for nine.

The CCF captured 26% of the vote and formed the opposition with seven seats (all of them in Winnipeg), and was joined on that side of the legislature by three Conservatives (who were opposed to the coalition), one independent and one Labor-Progressive (otherwise known as a Communist).

Campbell would go on to govern the province until 1958 but he would do so alone for nearly the whole time, as the PCs finally put an end to the coalition in 1950.

1962 Manitoba election

Duff Roblin secures third term

December 14, 1962

After a long period of rule by the Liberal-Progressives, Duff Roblin and the Progressive Conservatives scored an upset victory in the 1958 Manitoba election, securing a minority government. It was the party’s first victory since 1914 and came hot off the heels of John Diefenbaker’s federal landslide.

With a big and reforming legislative agenda, the PCs gained the support of the CCF in the minority legislature, as Roblin had positioned the party in the centre of Manitoba’s political spectrum — with the Liberal-Progressives to the right and the CCF to the left. When an opportunity presented itself, Roblin dissolved the legislature and won himself a majority government in 1959.

The first years of the Roblin government were focused on investment in the social sector, particularly education. But with Diefenbaker’s PCs reduced to a shaky minority in 1962, the likelihood of a federal election in 1963 seemed high. This might have pushed Roblin to call an early election for December 14, 1962.

Campaigning on a program of economic development — highways, northern development, the Red River Floodway — Roblin’s PCs were in a strong position. The Liberals had shed the ‘Progressive’ moniker and were now under the leadership of Gildas Molgat, someone who would keep the Liberals firmly on the right. The CCF was now the New Democratic Party under Russell Paulley, but the NDP was unable to make a breakthrough in its first campaign.

When the votes were counted, the Progressive Conservatives were returned with 36 seats, matching their total from 1959. Their share of the vote dipped only slightly, falling about a point to 45%. The Liberals gained two seats, winning 13, and increased their share of the vote from 30% to 36%. The NDP, though, fell seven points to 15% and only seven seats. A Social Crediter was also elected.

Roblin would win one more election in 1966 before stepping aside in 1967 to mount a (failed) bid for the federal PC leadership. Two years later, Ed Schreyer would form the first NDP government in Manitoba’s history.

1980 Manitoba Liberal leadership

Lauchlan for the Liberals

November 30, 1980

Being a Liberal in Western Canada was no treat in 1980. In the federal election held that year, Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals managed to get only two MPs elected west of Ontario — and both of those were in Manitoba. One of them was Lloyd Axworthy, who had previously been the one and only provincial Liberal throughout the region.

The Manitoba Liberals had been out of power for over 20 years by 1980 and were just coming off their worst election ever. In 1977, the Liberals under Charles Huband prevailed in only one seat (Axworthy’s) and took 12% of the vote. Huband resigned the next year.

The province, now governed by Sterling Lyon, a deep-blue Progressive Conservative, had become polarized between the right-wing Tories and the left-wing New Democrats, then under Howard Pawley. There was little place for the Manitoba Liberals in such a divided electorate — and with such an unpopular Liberal prime minister in Ottawa.

But the party still needed a leader, and two candidates were in the running by the time the party’s convention was held on November 30, 1980 at the Winnipeg Convention Centre.

The frontrunner was Doug Lauchlan, recently of Calgary. A former United Church minister and president of Mount Royal College, the Manitoba-born Lauchlan had left his job in Alberta to become an aide to Axworthy, who resigned his provincial seat to run for federal office and become Trudeau’s only Western cabinet minister. Lauchlan had tried, and failed, to become a Liberal MP himself, when he was defeated in a Calgary riding in the 1979 election.

But Lauchlan had the backing of the party establishment, particularly those with ties to the federal party.

Against him was Hugh Moran, a realtor from Portage la Prairie who represented the Manitoba Liberals’ dwindling rural base. Leaning into his Irish heritage, Moran’s white-and-green campaign signs featured a shamrock, a striking contrast to Lauchlan’s Liberal red-and-white.

Some 900 delegates and observers attended the convention, and when the ballots were counted Lauchlan won, taking 493 votes to Moran’s 300.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do,” Lauchlan said after his victory. “We’ve had a great launching pad, a magnificent experience here.”

He implored Manitoba Liberals to put their shoulder to the wheel, going out to meet voters and carve themselves a place on the province’s political spectrum.

“What’s that saying on Candid Camera about ‘surprise, you’re on Candid Camera?’” Lauchlan joked. “Well, some day, somebody’s going to knock on your kitchen door for a cup of coffee and it’s going to be me.”

Manitobans did not prove to be too enamoured with Lauchlan’s sense of humour. He led the party into the 1981 election, one that was polarized between Lyon and Pawley. In the end, he did even worse than Huband. With no seats and just 7% of the vote, the results still rank as the lowest point in the history of the Manitoba Liberal Party.

1981 Manitoba election

Howard Pawley leads the NDP back to power

November 17, 1981

After four years in office, the Progressive Conservative government under Sterling Lyon — a confrontational, pugnacious small-government conservative — was becoming increasingly unpopular in Manitoba. Lyon brought in fiscal restraints, fomenting opposition by groups affected by the government’s cuts, and seemed distracted by constitutional debates and “mega-projects”.

The New Democrats, who had governed Manitoba for two terms before the PCs came to power, were re-invigorated under the new leadership of Howard Pawley, who spent his time as opposition leader improving the state of the party’s organization.

Running as a relative moderate against the “neo-conservative'“ Lyon — whose party ran under the somewhat menacing slogan “Don’t Stop Us Now” — Pawley won a big majority with 34 seats, an increase of 11 since the 1977 election. The PCs lost 10 seats, dropping to 23, as the New Democrats won central and northern Winnipeg and rural seats in the north and east, while the PCs were pushed back to southern Winnipeg and the rural southwest.

The provincewide vote, however, was closer than the seat total might have suggested: 47% for the NDP and 44% for the PCs.

The Liberals, under Doug Lauchlan, were shut out and captured just 7% of the vote, which still stands as the Manitoba Liberals’ worst election performance in their history.

The Lyon government also still stands as the only single-term government in Manitoba.

The New Democrats would narrowly win one more election in 1986 under Pawley, but Gary Filmon would return the PCs to power in 1988 and stay there for the next 11 years.

1988 Manitoba NDP leadership

Gary Doer takes over

March 30, 1988

Seven years since being returned to power in 1981, the Manitoba New Democrats under Howard Pawley were struggling by 1988. The party had secured only a tenuous one-seat majority in the 1986 election and were hanging on by a thread following a resignation that left a seat vacant.

When it came time to vote on the NDP’s budget in 1986, disgruntled NDP MLA Jim Walding saw a moment to exact some revenge for what he felt was a snub by his party that kept him out of cabinet — a snub exacerbated when Walding found himself facing a challenge by one of Pawley’s aides for his own riding nomination.

Walding voted against the budget and Pawley’s government was defeated by a margin of 28 to 27.

It was not a good time for an election. Hurt by a big hike in auto insurance rates and Pawley’s support for the unpopular Meech Lake Accord, the New Democrats were trailing in third in the polls behind the second-place Liberals and a rejuvenated Progressive Conservative Party under Gary Filmon, who was taking the PCs into a more centrist direction after the confrontational conservatism of the Sterling Lyon years.

Pawley decided that the NDP’s best chance of survival was if he stepped aside, and when he called an election for April 26 he announced his own resignation and an NDP leadership race that would name his successor on March 30, 1988.

With little time to organize, there were still five candidates that emerged.

Gary Doer, minister of urban affairs and a former president of the Manitoba Government Employees’ Association first elected under the NDP banner in 1986, was the first to declare. He was seen as the front runner and he opened his leadership campaign admitting that the Pawley government had made mistakes.

Though he started out as a long shot, Doer’s main challenger turned out to be Len Harapiak, the minister of agriculture, who was described as “earnest, hard-working, soft spoken and family-oriented” by The Globe and Mail’s correspondent in Winnipeg. Like Doer, Harapiak had been first elected in 1986.

There was also Andy Anstett, attempting a comeback after being defeated in the 1986 election, Conrad Santos, an MLA, and Maureen Hemphill, minister of community services. Hemphill represented the party’s left wing, boasting she was not running “an establishment campaign”.

Doer had the backing of the urban white collar labour vote, and garnered endorsements from the Manitoba Federation of Labour and senior cabinet ministers. From Winnipeg, Doer counted on endorsements from influential New Democrats in Brandon and the rural areas of the province to broaden his appeal.

Harapiak, representing The Pas, had rural and northern support, along with the endorsements of more junior cabinet ministers. Both he and Doer were seen as moderates, but Harapiak had a longer history with the party after having run (and lost) as an NDP candidate on several occasions before his 1986 victory. Doer, by contrast, was seen by some as more of a newcomer.

The convention in Winnipeg included nearly 1,800 delegates, supplemented by satellite voting locations in Dauphin, Swan River, Flin Flon, Thompson and The Pas. Each riding was allowed to have one delegate for every 10 members in the riding, which meant parts of the province with stronger local organizations had more clout.

On the first ballot of voting, Doer emerged on top with 38% of delegates’ votes. Harapiak was not far behind with 33%, followed by Anstett at 19% and Hemphill with 10%. Santos garnered only five votes.

Hemphill backed Anstett for the next ballot of voting, but it didn’t help. Doer picked up 113 delegates, growing his support to 45%. Harapiak picked up 79 delegates and remained within reach of Doer with 38%, while Anstett saw his total drop by 27 delegates to just 18%.

An anyone-but-Doer movement emerged, as both Anstett and Hemphill got behind Harapiak. It almost succeeded, as Doer gained only 91 delegates on the third and final ballot to Harapiak’s 192.

But Doer won by a margin of 21 votes, with 835 delegates against Harapiak’s 814.

Doer had little time to get comfortable as NDP leader, as the election was only a few weeks away. A new face and some new energy was not enough, and the NDP suffered a big defeat, dropping from 30 seats and 41.5% of the vote in 1986 to just 12 seats and 24% in 1988. The Liberals under Sharon Carstairs formed the official opposition while Filmon and the PCs formed a minority government, which they were to increase to a majority two years later.

But despite the razor-thin leadership win and his electoral defeats in 1988 and 1990, Doer was able to stay on as leader of the Manitoba New Democrats. He’d lose again in 1995 before finally bringing the NDP back to power in 1999. Doer would serve as premier until 2009, when he stepped down and ended 21 years as leader of the Manitoba NDP — far longer than anyone else has ever held the title.

All because of 21 votes.

1993 Manitoba Liberal leadership

Liberals choose Edwards, but Lamoureux endures

June 5, 1993

Under Sharon Carstairs, the Manitoba Liberals achieved something they hadn’t enjoyed for decades: relevancy. In the 1981 election before her arrival, the Liberals were shutout of the Manitoba legislature entirely after being reduced to a single seat in 1977.

But Carstairs and her populist style earned the Liberals some respect. Taking advantage of the growing unpopularity of the NDP government she won a seat in 1986 and then leap-frogged the NDP entirely, winning 20 seats and 36% of the vote in 1988. The Liberals were just five seats short of the Progressive Conservatives, who formed government under Gary Filmon. For the first time in over 20 years, the Liberals won enough seats to form the official opposition.

The Liberals couldn’t move further ahead, however. Filmon secured a majority in 1990 and the Liberals were back to third party status with just seven seats.

Carstairs was criticized for squandering what was seen as an opportunity to finally put the Liberals back into power. By 1993, after leading the party through three back-to-back election campaigns and taking a prominent role in opposing the Charlottetown Accord, Carstairs announced her resignation in late 1992.

There wasn’t a lot of interest in the leadership contest to replace her, but the Manitoba Liberals had an opening. Filmon’s government was pushing through unpopular austerity measures and Gary Doer’s NDP still hadn’t shaken off its defeat from 1988. The Liberals, on the upswing elsewhere in the country and only months away from taking power federally, seemed to be a party heading in the right direction.

The race to decide who would take the party to the next level came down to two young MLAs from Winnipeg, both first elected in the 1988 election.

Paul Edwards, 32, was the favourite of the party establishment. He promised to keep the party in the middle of the spectrum, saying that “the genius of the Liberal Party is that it refuses to indulge in extreme positions.”

His one and only rival was Kevin Lamoureux, 31. According to the Canadian Press, the contest was between a “well-connected young Winnipeg lawyer [Edwards] or a hard-working ‘professional’ politician [Lamoureux].”

The Liberals were struggling to garner attention for the leadership race, with one debate held just a few days before voting attracting an audience of less than 50. But a little controversy helped the contest get into the headlines.

For the first time, the party was abandoning the delegated convention and instead sent out ballots to all 8,104 members eligible to vote. Members could cast their ballots by mail or at regional polling stations, with the result to be announced at the Winnipeg Convention Centre on June 5, 1993.

But there were some complaints that not everyone got their ballot in time to return it. The party responded by extending the deadline for receiving the mail-in ballots, a move that was decried not only by the Lamoureux campaign but by the leadership convention chairman, Ernie Gilroy, who said that he “no longer believe(d) that the candidates are playing on an even playing field”.

The argument was that the extension would give the lacklustre Edwards campaign more time to sign-up new members. Lamoureux’s team had managed more than twice as many new member sign-ups as the Edwards team, and it was argued the delay would let Edwards close that gap (it wasn’t explained why the Lamoureux campaign wouldn’t be able to also use the extra time to its advantage).

Following the outcry, the party reversed its decision and kept the deadlines as they were. In the end, it didn’t really make much of a difference — though it might have impacted turnout.

Just under 2,000 members of the Manitoba Liberal Party cast a ballot, a turnout of less than one-quarter. Of those who did manage to vote, Edwards received 56.1%. Lamoureux took the remaining 43.9%.

The low engagement in the party’s leadership race foreshadowed trouble ahead for the Liberals. The next provincial election was not held later that year, as some in the party had predicted, but would wait until 1995. Filmon and the PCs won that election with the NDP retaining its official opposition status. Edwards would manage to lead the party to just three seats (including Lamoureux’s, but not his own). Nevertheless, the 24% of the vote the Liberals captured in that election, though lower than what Carstairs managed in her last two outings, has yet to be bettered by the party.

While things didn’t get better for the Manitoba Liberals, Lamoureux’s political career was just getting going. He’d have a few more terms in the Manitoba legislature before making the jump to federal politics in a 2010 byelection and being one of the few federal Liberal MPs to survive the 2011 campaign. Since 2015, Lamoureux has served as the parliamentary secretary to the government House leader in Ottawa.

2016 Manitoba election

Heading toward the inevitable

April 19, 2016

There are few election outcomes that were as predictable, and from so far out, as that of the 2016 Manitoba provincial election.

If parties have a biological clock, the Manitoba NDP’s was long done ticking by 2016. The party had first come to power in 1999 under Gary Doer, but after 17 years, seven of them under the chronically-unpopular Greg Selinger, time was running out.

Doer had been a popular, pragmatic New Democrat during his time in office. But Selinger could never match his popularity, winning re-election in a tight contest in 2011. During that campaign, Selinger had made promises to Manitobans — and at least one of them he wouldn’t keep.

In spring 2013, Selinger announced that he would have to go back on a campaign pledge to keep the provincial sales tax at 7%. Instead, he would increase it by one point to help Manitoba’s fiscal situation. Manitobans didn’t like the increase, but they disliked that a promise had been broken even more.

Immediately, support for the NDP tanked. By June 2013 the party was trailing the opposition Progressive Conservatives by double-digits and Selinger was among the least popular premiers in the country. Selinger and the NDP would never recover.

Facing an unwinnable election, the NDP caucus was getting nervous. But when it was clear that Selinger would not step aside to try to give his party a fighting chance, five cabinet ministers publicly called for Selinger’s resignation and resigned their own cabinet portfolios. Still refusing to leave, Selinger instead called his challengers’ bluff — demanding a leadership race that could confirm his spot at the head of the party. His gamble paid off, but Selinger was only able to defeat his main challenger, Theresa Oswald, with 51% support on the final ballot. Hardly a resounding confirmation of his leadership.

As the dumpster fire within the Manitoba NDP raged, the PCs did their best to keep out of the flames. Needing to fill the vacancy left when Hugh McFadyen resigned following the 2011 campaign, the PCs opted for Brian Pallister. The long-time Conservative MP (who had run for the federal PC leadership in 1998) was acclaimed in 2012.

Pallister’s time as opposition leader was not without controversy or bizarre statements, including his deep and abiding distaste for Halloween. But these did not have an impact on the PCs’ support, even if Manitobans admitted to less support for Pallister himself than the party he was leading.

When the campaign was finally kicked off in March 2016, Pallister’s PCs embarked on a safe front-runner’s campaign with few detailed promises. Two things Pallister did make clear, though, was that he’d reverse the sales tax increase and that this campaign was a referendum on Selinger. To drive the point home, he launched his campaign in Selinger’s own St. Boniface riding.

There was nothing the NDP could do to stem the tide. The desire for change was just too strong in Manitoba. Nearly a quarter of Selinger’s caucus wasn’t running for re-election and the internal divisions within the party made for an easy target for the PCs, with one attack ad asking “if even the NDP can’t trust Greg Selinger, how can Manitobans?”

With the NDP so unpopular, there might have been an opportunity for the Manitoba Liberals to make a breakthrough. Some polls were showing the party, with only one seat in the legislature, was running ahead of the NDP. Coming only a few months after Justin Trudeau’s 2015 federal election victory, which included many Liberal victories in Winnipeg, the election’s prospects looked promising for the Manitoba Liberals.

But their campaign fell apart. Under rookie leader Rana Bokhari, the party’s campaign was plagued by gaffes, internal disputes and a general air of amateurism. The party failed to run a full slate when a few of its candidates were disqualified and others had to be dropped. Any chance the Liberals had to displace the NDP as the second-place party appeared slim by election day.

As expected, the PCs won a sweeping majority. They more than doubled their seat count to 40 and increased their vote share by nine points to 53%. It was one of the biggest victories in the party’s history.

Not only did the PCs push the New Democrats outside of small-town and rural southern Manitoba, it was also able to win 17 seats in Winnipeg itself. The New Democrats suffered losses throughout the province, losing votes to the PCs in southern Manitoba, the Liberals in northern Manitoba and to both parties in Winnipeg. Selinger promptly resigned as NDP leader. Bokhari, who failed to win her own seat, eventually stepped aside as well.

The Manitoba Progressive Conservatives would have at least one more victory in them when the party won another big majority government in the 2019 election. But Pallister, like Selinger before him, soon became a drag as his own popularity plummeted and the NDP moved back ahead of the PCs in the polls. Unlike Selinger, though, Pallister stepped aside to keep his caucus together and to give a chance to his successor.

In October, we’ll find out if that successor, Heather Stefanson, will be able to turn things around for the PCs — and avoid what looks like the inevitable.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Manitoba and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Manitoba Premiers of the 19th and 20th Centuries, edited by Barry Ferguson and Robert Wardhaugh

John Bracken: A Political Biography, by John Kendle