#EveryElectionProject: Canada

Capsules on Canada's federal elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about federal elections and leadership races.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1867 Canadian federal election

Canada’s first election

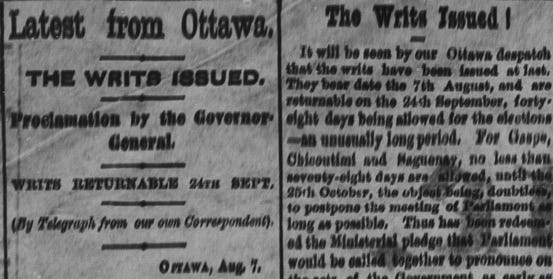

August 7 to September 20, 1867

When Confederation became reality on July 1, 1867, there were many things to get done. For starters, Canada had only four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Recalcitrant colonies such as Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland would have to be wooed. A railway would have to be built to link central and eastern Canada with the west before those settlements could be brought into the Union. The sparsely-populated and under-developed collection of British territories lying in the shadow of the American colossus to the south, itself self-confident and powerful after the end of the Civil War, would have to be turned into a country.

But first — an election.

As the main architect of Confederation, John A. Macdonald was invited to form Canada’s first government. Once sworn in, Macdonald shortly sent Canadians to the polls for the first time in a national election. But not all at the same time.

With no standardized election laws, campaigns were held in each of the four provinces according to their pre-Confederation electoral regulations. Who could vote varied from province to province, but it was largely limited to property-holding men. In Ontario, for example, it’s been estimated that only 16.5% of the population was eligible to vote.

How Canadians voted also varied. In Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, voting was done openly in public, often with a show of hands. Only New Brunswick had a secret ballot. Nova Scotia held elections in all ridings on the same day, while the other three held them on different days. The result was that voting took place at different times between August 7 and September 20, 1867.

Macdonald held many advantages. As leader of the Liberal-Conservative Party (as it was then called as a nod to the cross-party coalition of Liberals and Conservatives that worked together to bring about Confederation), Macdonald grouped together most of the pro-Confederation forces across the country. It was a more properly-organized party than the one on the other side of the aisle. The government’s powers of patronage, which Macdonald held and freely used, helped a great deal.

In Quebec, the Bleus were aligned with Macdonald while in Ontario he had the support of John Sandfield Macdonald, a Liberal member of his coalition. Rejected by other Liberals as little better than a traitor, the two Macdonalds hunted “in pairs”, splitting Ontario’s provincial and federal ridings between them to prevent John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives from having to face John Sandfield Macdonald’s “Coalition Reformers”. If both parties had interested candidates in a particular riding, they’d encourage one to run for provincial office and the other to stand for the federal campaign.

(Of course, running for both was an option. The first premiers of Quebec and Ontario were also sitting MPs.)

In Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, where elections could be held on different dates, Macdonald ensured that the more reliably Conservative seats voted first, in order to build some momentum that could be carried forward into less friendly parts of the country. Where voting was held over two days, the Conservatives could use bribery and threats to get out their vote on the second day when they found they were trailing after the first day of polling.

The Liberals weren’t above those tactics, but they were far more disorganized and had fewer resources at their disposal. They also had no official leader, George Brown being the de facto head of the Ontario Liberals, Antoine-Aimé Dorion the leader of the Rouges in Quebec. The Liberals (or Reformers, as they were often called) brought together those forces who had opposed Confederation, but were now largely reconciled to try to make it work.

Opposition to Confederation was strongest in Nova Scotia, where Joseph Howe led a slate of Anti-Confederate candidates. Mostly Liberals, the Antis didn’t want to try to make Confederation work. But they were hardly a united bunch. Some wanted to repeal Confederation entirely, while others wanted to amend it. Another group wanted Nova Scotia to deny that the Dominion existed, and refuse to send MPs to Ottawa.

The Antis were not incapable of overly-heated rhetoric. In one speech, Howe said that if “the British forces were withdrawn … and this issue were left to be tried out between the Canadians and ourselves, I would take every son I have and die on the frontier, before I would submit to this outrage.”

Violence was never far below the surface. If politics can seem nasty in the 21st century, it could be downright dangerous in the 19th. Alexander Mackenzie, a future prime minister and one of the top Liberals in Ontario, nearly fell into the hands of an angry mob while on the hustings. Mackenzie was prevented from speaking at a rally in Plympton and, when he tried to depart, the crowd blocked him from leaving and attempted to overturn his carriage and pull Mackenzie and the man he was travelling with into the crowd. When they finally got away, a high-speed horse-and-wagon chase followed, with Mackenzie’s pursuers “yelling and howling”, according to the Sarnia Observer, until Mackenzie’s carriage managed to escape.

No election was held at all in the Quebec riding of Kamouraska when a riot broke out on voting day, fought with “stones, cordwood and axe-handles”, according to author Norman Ward. “When I was dragged away,” recalled the returning officer, “through the yelling and vociferating mob, I am not conscious that I was struck, but in my agitated state I may have been struck without noticing it … and from my feelings next morning, at the back of my head, I am convinced that I had a few blows.”

There was little doubt that, with all of the incumbent government’s advantages, Macdonald’s Liberal-Conservatives would win. The party captured 100 seats (according to the Library of Parliament, though tallies differ from source to source), winning 49 in Ontario and 47 in Quebec, but just four in the Maritimes.

The Liberals won 62 seats, including 33 in Ontario — largely in the western portion of the province where they were strongest. George Brown, however, was not among the Ontario MPs elected and the long-time leader of the Reformers refused to stand in another constituency where voting had yet to take place when his defeat was announced at the end of August. The Rouges won 17 seats in Quebec and 12 of 15 in New Brunswick, where the Conservatives won the other three.

The Anti-Confederate vote in Nova Scotia was strong, with Howe being one of 17 Antis elected in the province. Only one Conservative, future prime minister Charles Tupper, withstood the Anti-Confederation wave.

(Alfred Jones, elected in Halifax, is listed as a Labour candidate by the Library of Parliament. Also, the record books for 1867 do not assign a party affiliation to dozens of defeated candidates, hence the large share of the vote awarded to “unknown” in the chart above.)

Macdonald was dismissive of the Anti-Confederate victory, calling it “a small cloud of opposition no bigger than a man’s hand.” He had a point. Within a few years, he would co-opt much of the party — including Howe, who joined Macdonald’s cabinet once the British government refused to reconsider Canadian Confederation.

It would take some time before Canada’s elections became a little more modern. The secret ballot and single-day elections would have to wait until Mackenzie’s Liberals came to power in 1874, largely in reaction to Macdonald’s under-handed campaign tactics. But Canada had its first election in the books.

1874 Canadian federal election

John A.’s only defeat

January 22, 1874

For nearly all of the last half of the 19th century, John A. Macdonald dominated Canadian politics. With the exception of a brief interlude, Macdonald was prime minister from Confederation in 1867 to his death in 1891.

But that brief exception nearly ended his career prematurely.

After winning Canada’s first election, Macdonald had a rougher go in 1872. He was facing opposition in Ontario over his handling of the economy and relations with the United States, and discontent in the West with the slow development of the transcontinental railway.

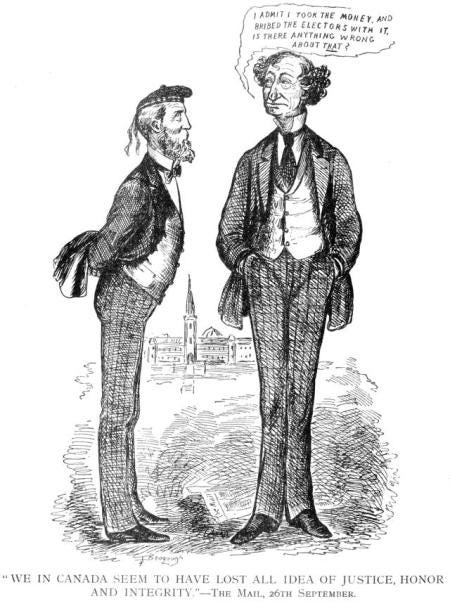

His desperation was such that he could not turn down a huge influx of cash from Hugh Allan, who just happened to be negotiating with the government for the rights to build the Pacific railway.

Facing a stiff fight in his Kingston riding, Macdonald needed money. In an act of political self-destruction, he sent off and signed a telegram to Allan’s lawyer:

“Immediate private. I must have another ten thousand. Will be the last time of calling. Do not fail me. Answer today.”

Three days later, the reply came back in the affirmative.

In all, Allan would contribute $350,000 to the Conservatives’ re-election efforts, an enormous sum by the standards of the day (and enough to turn heads even now). That money was sprinkled across the country in ways that violated election laws at the time.

With Allan’s help, Macdonald narrowly secured re-election, but it wasn’t long before the nitty-gritty details of what would become the Pacific Scandal started leaking out. By the end of 1873, the telegram (and others) had been re-printed in the press and Macdonald’s premiership was over. He resigned. His replacement was the Liberal leader, Alexander Mackenzie.

Like Macdonald, Mackenzie was a Scottish immigrant. A solid, uncharismatic, morally upright and rigid stonemason from Sarnia, Mackenzie was determined to run a clean administration. After setting up his government, he dissolved parliament and called an election for January 22, 1874.

Though it wasn’t written into law yet, Mackenzie went ahead with one of the reforms he meant to enact to clean up politics by holding elections across the country on the same day. That wasn’t the practice in 1867 or 1872. Macdonald had used this to his advantage, scheduling elections in safe ridings earlier in order to build up some momentum for more difficult contests later. By the time Mackenzie’s time in office was over, he’d bring in other election reforms like a secret ballot and an expanded franchise.

Mackenzie didn’t need to abuse the electoral system to win in 1874. The Pacific Scandal was enough to tar Macdonald’s Conservatives and make them unelectable.

The Liberals secured 131 seats, a gain of 38 from the 1872 election. Their share of the vote jumped five points, while the Conservatives lost 38 seats and nine percentage points. (The political affiliation of candidates that got about 24% of the vote is unknown, according to the Library of Parliament’s website.)

The Liberals did very well in the Maritimes and won more than two-thirds of the seats up for grabs in Ontario. The Liberals even won a slight majority of seats in Quebec, a province that was normally far friendlier to the Catholic Church-backed bleus than the rouges in the 19th century.

In a note to one of his newly-elected Liberal MPs, Mackenzie was exultant. “What a slaughter,” he wrote. “The old corruptionists are fairly stupefied by our success.”

The Conservatives still held on to some of their seats in Ontario and Quebec and won in British Columbia, in part because Mackenzie had criticized the “impossible terms of union” that brought B.C. into Confederation. He wasn’t keen on Macdonald’s expensive railway policy, hoping to use waterways as much as possible between Georgian Bay and the Rockies to save money instead.

Mackenzie’s administration would prove to be short-lived, as it struggled through a global economic depression in the 1870s. Mackenzie was a micro-manager, taking on the huge public works portfolio himself in order to ensure it was kept clean. He wasn’t willing to play the same patronage game that Macdonald had mastered, meaning no Liberal network of grateful office-holders was established.

Macdonald considered retirement, but instead embarked on a new campaign with renewed energy, pushing the protectionist National Policy that would become the keystone policy of the Conservative Party for the next few decades. Like Mackenzie King, who was in opposition from 1930-35 and is the only prime minister to serve longer than him, Macdonald would benefit by being out-of-office for the worst of a depression. He’d be re-elected in 1878 and would never lose an election again.

1904 Canadian federal election

Laurier wins his third consecutive election

November 3, 1904

Already eight years into his time as prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier was at the height of his power when he called the 1904 federal election. He had already beaten Charles Tupper twice (in 1896 and 1900) and the 1904 election marked what would be the first of four contests Laurier would fight against Conservative leader Robert Borden.

The turn of the century was a time of rapid economic growth in Canada and a boom in immigration that settled the West. Tensions between English and French Canadians had died down under Laurier and all seemed well in the land to the (white, male) voters eligible to cast a ballot.

The Liberals were rewarded with what would be their biggest victory under Laurier and, with the exception of the 1940 election, the last time the party would capture a majority of ballots cast. The Liberals took just under 51% of the vote and won 137 of the 214 seats up for grabs, the equivalent of winning about 216 seats in today’s 338-seat House of Commons. They swept Nova Scotia, Borden’s home province, and dominated both Quebec and Western Canada.

Only in Ontario and P.E.I. did the Liberals fail to win the most seats.

The Conservatives captured around 46% of the vote and won 75 seats. But, despite the defeat, they’d stick with Borden. And they’d stick with him again even after he lost a second time in 1908. That patience would pay off when he would finally bring the Conservatives back to power in 1911.

1911 Canadian federal election

The reciprocity election that defeated Wilfrid Laurier

September 21, 1911

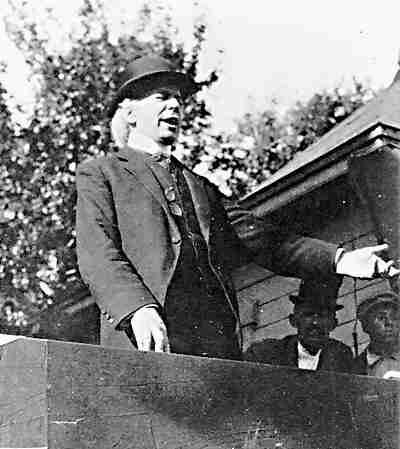

Wilfrid Laurier was the giant of Canadian politics during the first decade of the 20th century, easily winning re-election three times after coming to power in 1896. The country was prosperous and growing, becoming more urban and industrialized and attracting immigrants who helped boost Canada’s population from 5.4 million to 7.2 million between 1901 and 1911 — a rate of growth the country has never since matched.

Nearing 70 years old in 1911 but still carrying himself with the dignity and sense of fairness that earned him respect from both English and French Canadians, Laurier had governed the country for 15 years and had led the Liberal Party for more than two decades. He had lost his first election as leader in 1891 on the issue of freer trade with the United States. John A. Macdonald, in his last campaign before his death, wrapped himself in the Union Jack and his long-standing National Policy of protective tariffs and carried the country one last time on the slogan of “The Old Flag, The Old Policy, The Old Leader.”

Twenty years later, though, Laurier thought the time was ripe for his Liberals to finally achieve their goal of free trade with the U.S., especially since President William Howard Taft seemed amenable to a deal. Envoys were sent to Washington, D.C. and came back with an agreement.

When W.S. Fielding, Laurier’s finance minister, announced its details in the House of Commons, the Conservatives on the opposition benches were gob smacked. While they expected something had been worked out between Fielding and the Americans, they had no idea of its scope: free trade for agricultural products and protective tariffs for most manufactured goods. It would open up the huge U.S. market for Canadian farmers in the West while protecting the industrial interests of Central Canada.

Robert Borden, leader of the Conservative opposition since 1901, initially thought this meant another defeat was on the horizon. Contrary to modern practice, the Conservatives had stuck with Borden despite two consecutive elections defeats under him in 1904 and 1908. His hold on the party was shaky, but he had survived. This deal would sink him, perhaps for the last time.

Fellow Conservatives around the country, however, weren’t so pessimistic. Reciprocity had defeated the Liberals in 1891 and it could do so again. Manufacturers and financiers in Toronto and Montreal were ready to fight to protect their interests, and would fund a nationwide campaign to denounce reciprocity with the United States. Conservative premiers in British Columbia, Manitoba and Ontario were ready to go to bat for Borden to finally defeat the Liberals.

For opponents to freer trade, which included a ‘Toronto 18’ of business leaders and Liberals who publicly spoke out against the deal, Laurier’s gamble had given them a golden opportunity. Cheaper goods and bigger markets might seem appealing, they claimed, but they would destroy Canadian producers. Worse, a closer relationship with the United States would inevitably lead to political union and annexation. Reciprocity meant turning away from the British Empire when it most needed Canada.

War clouds were gathering over Europe as an increasingly belligerent Germany threw its weight around international affairs. Wanting its own place in the sun and greater dominance on the Continent, Germany had embarked on a naval arms race with Great Britain, then the world’s foremost naval power. Britain needed to keep its advantage — and maybe Canada could help.

Borden and other imperialists wanted Canada to make a direct contribution to the British treasury, sending money to build warships for the Royal Navy. But Laurier wanted Canada to maintain some level of independence and proposed instead his Naval Service Act, which called for the construction of a small Canadian force (dubbed a ‘tin-pot navy’ by opponents) instead. The Conservatives believed when the Empire called Canada should only say “ready, aye, ready”. What Laurier proposed smacked of anti-British treason.

For French-Canadian nationalists in Quebec, however, it was just the opposite. Henri Bourassa, nationalist firebrand and editor of Le Devoir, argued that the creation of a navy was only the first step toward conscription to fight in British wars. While Laurier would be accused of being a traitor to the Empire in English Canada, he would also be accused of being a traitor to his ‘race’ in French Canada.

Suddenly, things were looking up for Borden and the Conservatives. They had the backing of powerful, well-funded interests and a patriotic appeal to make to the people. Borden also gave his acquiescence to a parallel campaign in Quebec, led by his Quebec lieutenant Frederick Monk and Bourassa, against the Liberals over the naval issue.

Laurier denounced the ‘unholy alliance’ between Borden and Bourassa. Frustrated that he couldn’t get his reciprocity legislation through the House of Commons (the closure mechanism that can shut down debate in the House today didn’t exist at the time), he decided to take the question to the people and called an election for September 21, 1911 — less than three years after the previous election of 1908.

Laurier had some reason to be confident. He had seen off the Conservatives four times before. He was still widely respected, even revered, and the slogan of “Laurier and Larger Markets”, though perhaps lacking an emotional appeal, would speak to voters’ logic. If that wasn’t enough, Laurier had the assistance of provincial Liberal governments in most provinces and the assured support of voters in the Prairies, whose farmers had always clamoured for access to the American market.

But Laurier’s old charm was starting to wear off by 1911 and he and his Liberal government were showing their age. The cabinet had hardly changed since 1896 and Laurier’s old-style, classic liberalism was starting to appear out of date as Canada modernized and government intervention, even by Conservative governments, was becoming more popular.

Against his atrophying political machine, particularly in Ontario, Laurier faced skilled Conservative premiers in Richard McBride in British Columbia, Rodmond Roblin in Manitoba and James Whitney in Ontario, who all put their political organizations (and some times their civil servants) to work to elect Borden. Even Laurier’s Quebec base was threated by Bourassa and Monk, and Borden accordingly kept a wide berth of the province, visiting only once on his way to tour the Maritimes.

The election, which Laurier hoped to have decided on the issue of an expanding economy thanks to access to the huge American market, became an emotional appeal to patriotism. Even Rudyard Kipling was drafted to aid the anti-reciprocity campaign, writing in Conservative-friendly newspapers that “it is her own soul that Canada risks today.”

The Liberals weren’t helped when the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Champ Clark, stated that he longed to see the day “when the American flag will float over every square foot of the British North American possessions, clear to the North Pole,” but the claims of Laurier’s limited free trade leading, first, to complete free trade and, second, to annexation by the United States were dishonest at best, outright lies at worst. At a time when pro-Empire and anti-American sentiment was high, they were used to devastating political effect and casted Laurier’s plan as a betrayal of the British and a surrender to the Americans.

The Conservatives emerged with 135 seats, an increase of 49 over their performance in the 1908 election. Laurier and the Liberals were defeated.

The Conservatives made inroads in the Maritimes with 16 of 35 seats and a breakthrough in Quebec with 28 seats, up from just 12 in the previous election, thanks to the efforts of Bourassa and Monk. Sealing the Liberals’ fate was Ontario. Whitney’s political machine helped deliver 73 of 86 seats to the Conservatives (a gain of 25), while Roblin secured eight of 10 seats in Manitoba and McBride swept all six of B.C.’s seats for Borden.

(Conservative figures here include Independent Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives and Nationalists who ran with the blessing or acquiescence of the Conservatives. The lone Labour MP was trade unionist Alphonse Verville, who supported the Liberals and ran without opposition from that party. However, he was initially elected to the House by defeating a Liberal candidate in a Montreal byelection in 1906.)

The Conservatives won just over 50% of the vote as Liberal support fell 3.5 points to 45.8%. Laurier captured just 85 seats, a loss of 48 from 1908. The party had lost ground in Quebec but still held on to 36 seats in the province, while reciprocity helped the Liberals carry 15 of 17 seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Among the defeated were Fielding and Mackenzie King, a future prime minister. Among the elected were future Conservative prime ministers R.B. Bennett in Alberta and Arthur Meighen in Manitoba.

It was a soaring victory for Borden and the Conservatives and a painful defeat for Laurier. He had gauged his political future on a long-cherished dream of free trade was was accused of betraying both his own countrymen and Canada’s British connection.

“I am branded in Quebec as a traitor to the French,” he said while on the hustings, “and in Ontario as a traitor to the English. In Quebec, I am branded as a jingo and in Ontario as a separatist. In Quebec, I am attacked as an imperialist and in Ontario as an anti-imperialist. I am neither. I am Canadian.”

Borden’s calculated move to sidle up to Quebec nationalists proved short-sighted. Not needing them after winning such an enormous majority, he sidelined them and quickly lost their support. In short order, Bourassa and his nationalists would turn on Borden. As with John Diefenbaker and Brian Mulroney in later years, Borden’s attempt to draw Quebec nationalists into his coalition would eventually collapse.

His spurning of free trade also angered Western farmers, who felt disrespected and unrepresented by Central Canada. They would find that voice in the rise of the Progressive Party which, along with Quebec’s fierce opposition to the Conservatives after they brought in conscription during the First World War, led to the party’s catastrophic defeat in 1921.

But in 1911, that was all in the future. Borden’s victory would spell the end of reciprocity for nearly another eight decades and would give him the burden of leading the country through the First World War. That next election, perhaps Canada’s ugliest, would prove to be the last showdown between Borden and Laurier.

1938 Conservative leadership

A job looking for a man

July 7, 1938

Poor Robert Manion.

The Conservatives, through their various iterations, have had a number of leaders who never became prime minister. The last few might one day be forgotten, but that hasn’t happened just yet. Robert Stanfield has an airport named after him and John Bracken, in addition to being premier of Manitoba for decades, was responsible for bolting the word “Progressive” to “Conservative”, a legacy that still echoes in premiers’ offices from Winnipeg to Halifax.

But Robert Manion? If any past Conservative leader elicits a shrug, it’s him.

Manion’s rise to the leadership of the Conservative Party (known as the National Conservative Party at the time) occurred in 1938 in the shadow of another looming world war and that of an outgoing giant in the party.

R.B. Bennett had led the Conservatives since 1927, leading them to victory in 1930 and having the misfortune of governing Canada through the toughest days of the Great Depression. Accordingly, Bennett’s government was defeated in 1935 and, by 1938, it was time for Bennett to step aside and retire to an estate in England.

The Conservatives held their convention between July 5 and 7, 1938 in Ottawa. It would feature a few final speeches by Bennett, who was still seriously considering staying on as leader. Former Ontario premier Howard Ferguson was one of the big proponents for a Bennett comeback, but it was only when former prime minister Arthur Meighen, who also speechified at the convention, talked him out of it that Bennett finally admitted his political career was over.

“To have declared myself a candidate to succeed myself, at the eleventh hour,” he wrote in a letter after the convention, “would have been rather dishonourable.”

It would have been unfair to those candidates who had declared themselves under the assumption that R.B. was leaving. First among these, and the odds-on favourite to win, was Robert Manion.

A physician, Irish Roman Catholic and MP for the northern Ontario riding of Fort William until his defeat in 1935, Manion had been a cabinet minister in both Meighen’s and Bennett’s governments and had finished fourth in the 1927 convention. A veteran of the First World War who was liked within the party, the “white-haired, clean-cut” Manion had his biggest support base in Quebec. He was a Roman Catholic married to a French Canadian, qualities that promised success for Conservatives in Quebec and discomfort for elements within the party that weren’t too friendly to Roman Catholics or French Canadians, particularly when it came to their questionable attachment to the British Empire.

Among those opposed to Manion was Meighen, who still held influence within the party. Meighen was instead backing Murdoch MacPherson of Saskatchewan.

MacPherson, “a youngish man of force and vigour from the Prairies”, had been a cabinet minister in Saskatchewan’s one-term Conservative government. He was seen as a serious underdog until he gave a good speech at the convention, catapulting himself into contention.

Also backing MacPherson was John Diefenbaker, then the leader of the seatless Saskatchewan Conservative Party. Diefenbaker would eventually have designs on the national leadership himself, but for now he was complaining about the national party’s lack of support for his recent provincial campaign, guilting the chairman of the convention to send him $125 to cover his travel expenses to Ottawa. Diefenbaker also talked a Regina supporter into paying for his railway tickets for him and his wife, something Diefenbaker declined to mention when he accepted the $125.

In addition to Manion and MacPherson, there were three other candidates, all Toronto-area MPs: Joe Harris, Earl Lawson and Denton Massey. They were considered long-shots and fell out of contention as soon as MacPherson had taken the stage.

It was a tumultuous convention, as the Quebec delegates (flush with victory after Maurice Duplessis’s win in 1936) challenged the party’s position on defense that put it lockstep behind the British. There were also divisions between the left and right wings of the party.

“God help you because of the reaction of this party,” said W.D. Herridge on stage, after he was booed and heckled for putting forward progressive economic policies that the convention rejected. He warned that without adopting this approach, “the pages of history will record this as the day of [the party’s] funeral.”

When the voting was finally held, Bennett, Meighen and Ferguson were nowhere to be seen. Douglas R. Oliver of The Globe and Mail put it thusly: “the big guns which boomed in convention and outside convention, yesterday, and the day before that, and the day before that, but never a boom today.”

Though MacPherson had tightened the betting odds, on the first ballot it was Manion who emerged as the eventual choice of the party. He had 726 votes, just 60 short of what was needed for an outright victory. MacPherson trailed with 475 and the three southern Ontarians were further back.

Lawson was eliminated and threw his weight behind MacPherson. Neither Harris nor Massey stepped aside, but the bulk of their delegates went elsewhere. MacPherson gained the most votes on the second ballot, pushing his share up 173 votes to 648, but Manion earned enough new support (104) to win with 830.

He had been the favourite all along, even if no one seemed all that excited about the prospect. Oliver called the convention “the tale of a job that went looking for a man”, and the Conservatives had their man in Manion.

Manion had no seat in the House of Commons, but would contest and win a byelection in November 1938. He would eventually lead the Conservatives into the wartime 1940 federal election, pitching himself and his party as a National Government to mimic Robert Borden’s Union Government that had attracted Manion to the party in the first place.

It didn’t work. The Conservatives did no better than the trouncing they had received in 1935. Manion went down to personal defeat in his riding. Mackenzie King won the greatest victory he would as prime minister. By the next election, the war was (all but) over, Manion was dead and the National Conservatives had become the Progressive Conservatives. Not until 1957 and the leadership of John Diefenbaker, his $125 long spent, would the party be back in power.

1956 Progressive Conservative leadership

Dief becomes the Chief

December 14, 1956

The Progressive Conservatives were starting to feel like maybe they had a little wind in their sails.

After two decades on the opposition benches, they had staggered the Liberals with a bruising fight over C.D. Howe’s controversial TransCanada pipeline project. With an election just a year away, the PCs’ prospects were suddenly looking up in 1956.

They still faced serious challenges, however. The Liberals had been in office since 1935. Louis St-Laurent, who had taken over from Mackenzie King in 1948, seemed to be in cruise control as a benevolent chairman of the board. After leading the country out of the Great Depression, through the Second World War and into its postwar economic boom, the Liberals were more of a Canadian institution than a mere political party.

When Canadians had last gone to the polls in 1953, they had rubber-stamped St-Laurent’s government by awarding the Liberals 48% of the vote and 169 seats. The PCs under former Ontario premier George Drew managed just 51 seats and 31% of the vote. Even if the Tories were smelling a little blood in the water in 1956, defeating the Liberals still seemed unlikely with Gallup awarding the governing party between 47% and 54% in polls conducted that year, compared to just 28% to 34% for the PCs.

Plans for the final sprint toward the election expected to be called in 1957 had to be put on hold, however, when Drew resigned the leadership. His health had deteriorated and he had no choice but to step aside.

Everyone knew who his replacement would probably be: John Diefenbaker, 61, the bombastic and theatrical partisan performer who had assailed the Liberals in the House of Commons since being first elected in 1940. A former leader of the Saskatchewan Conservatives, Diefenbaker was, by now, a perennial candidate with a national profile. He had finished a distant second to Drew in the 1948 leadership contest. He had finished an even more distant third to John Bracken back in 1942. It would finally be Diefenbaker’s time.

That is, unless his determined opponents within the party could stop him.

An “Old Guard” of Tories who had run the party for decades didn’t quite like Diefenbaker, a somewhat awkward, unpredictable and grudge-holding Prairie populist. Diefenbaker was a proponent of “One Canada” and of unhyphenated Canadians, a position that was at odds with the PCs’ traditional nationalist allies in Quebec. Someone needed to run as the anti-Diefenbaker candidate.

But it was hard to find someone willing to do it. The Old Guard was looking increasingly old and and out-of-touch with the modern PC Party. Diefenbaker had allies in provincial capitals in Winnipeg, Toronto, Fredericton and Halifax — important establishment figures like Leslie Frost and Hugh John Flemming and future stars like Duff Roblin and Robert Stanfield. Diefenbaker had the backing of nearly all of the PC caucus (save a few of the front-benchers). Potential rivals were approached but they declined, leaving the unenviable task to Donald Fleming.

Fleming, a bilingual Toronto MP who had finished third in the 1948 leadership contest, emerged as Diefenbaker’s chief rival. While Diefenbaker had the support of the West, Fleming had the backing of Quebec. But he had little more than that.

Also throwing his hat into the ring was Davie Fulton, the youngest candidate of the three at just 40 years old. Fulton represented a riding in British Columbia and was a supporter of Diefenbaker. He was just hoping to make a name for himself for a future run. Plus, he was a Roman Catholic — and some elements within the party believed a Catholic leader would tank them in parts of Ontario and the Maritimes.

Fulton recognized he wouldn’t win this race. Political observers, the press gallery and most of the PC Party agreed that Fulton wouldn’t win — and neither would Fleming. A Gallup poll of PC voters showed 55% support for Diefenbaker. Fleming had just 14%.

Diefenbaker’s position as the likely winner was further solidified with his performance during the international crises that distracted Canadians throughout the fall of 1956: the Soviet Union’s brutal repression of an uprising in Hungary and the attack on Egypt by Great Britain, France and Israel. While Lester Pearson would earn most of the praise for his involvement in brokering a solution to the Suez Crisis, Diefenbaker used the opportunity to present himself as a responsible national leader of the opposition.

Nevertheless, Diefenbaker’s campaign took no chances. The paranoid vindictiveness that would soon become apparent when Diefenbaker became prime minister in 1957 was reflected in his campaign, which went hard after Fleming despite the inevitable victory.

Attacked as the candidate of the establishment, Fleming found it difficult to garner support. “It became obvious that even those who were not ready to support Diefenbaker were reluctant to show their colours against him,” Fleming later said. “This was based in some cases on the belief that he was bound to win, in others on fear of his reputed vindictiveness. I doubt if they gained anything from their abstention.”

Dalton Camp, a brilliant political strategist who would eventually become Diefenbaker’s nemesis, observed in the Diefenbaker campaign “an undercurrent of malice, a sense of an impending blood-letting, in which the victorious would all avenge the past.”

It wasn’t the only omen of what would come. When PC delegates gathered in Ottawa for the leadership vote, Diefenbaker was sharply criticized by his few Quebec supporters for his decision to have his two nominators be English-speakers from the West and East. Diefenbaker refused to back down. While both Fulton and Fleming made one of their nominators a Quebecer, Diefenbaker didn’t.

It wouldn’t be the last time Diefenbaker would reveal an insensitivity to Quebec — one that would eventually hurt him in the future.

But December 14, 1956 was a day of vindication for Diefenbaker, who had been rejected and spurned so often before.

As expected, Diefenbaker won an emphatic first ballot victory with the support of 774 delegates, or about 60% of ballots cast. Diefenbaker didn’t do well among the Quebec delegates (many of whom walked out of the convention when the results were announced), but those in the West and in Ontario carried the day for him.

Fleming finished with 393 votes (31%), while Fulton came third with 117 (9%).

The polls didn’t improve for the PCs after Diefenbaker’s victory and he would remain an underdog right up until election day, when he scored an upset minority win in 1957 over St-Laurent’s Liberals.

Though Drew won the leadership of the PCs with a little more of the vote in 1948 than Diefenbaker did in 1956, no subsequent candidate for the leadership of the Progressive Conservatives, Canadian Alliance or the modern Conservative Party ever matched Diefenbaker’s big first ballot win — until Pierre Poilievre beat it in 2022.

It isn’t the only parallel that can be drawn between the political careers of these two Conservative leaders, whose take-no-prisoners, partisan street-fighter approaches had their strengths, as well as their weaknesses.

1961 New Democratic Party leadership

Tommy Douglas takes over the new NDP

August 3, 1961

When about 1,800 delegates headed to the Ottawa Coliseum in early August 1961, their task was not only to found a new party but to determine who should lead it.

This new party would be the successor to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, originally founded in the 1932. The CCF was steeped in the Prairie socialism and social gospel that emerged between the world wars, but by the 1960s it was seen as a little dated.

The results of the 1958 election made that clear.

Though the CCF once enjoyed a surge in the polls during the Second World War and had managed to form government in Saskatchewan since 1944, it was unable to make a breakthrough at the federal level. In its last election under M.J. Coldwell, the CCF was reduced to just eight seats when John Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservatives won their landslide victory in 1958.

Saskatchewan, the heartland of the CCF, elected only a single CCF MP — and it was Hazen Argue, not M.J. Coldwell.

It punctuated what was already a lively discussion within CCF circles: it was time to create a new party that would unite the western, farmer base of the CCF with the urban energy (and financial resources) of the labour movement. The CCF and the Canadian Labour Congress decided to get the ball rolling in that direction to create this new party of the left for the modern age.

But who would lead it? Some thought it should be David Lewis, an influential behind-the-scenes figure within the CCF. But to prevent the traditionalists in the CCF from believing they were being swamped and taken over by the labour movement in Central and Eastern Canada, Lewis felt it couldn’t be him. It had to be T.C. Douglas, Saskatchewan premier and the CCF’s most successful politician in the country.

Tommy Douglas wasn’t so sure, though. The Saskatchewan CCF had done just fine without close affiliations with the labour movement. Linking itself with unions could cost the CCF its rural support in his home province. Douglas thought the national CCF and the CLC were moving a little too quickly for his taste.

But plans to create the new party — candidates were already starting to contest byelections under the “New Party” banner — went ahead. Coldwell, seatless and aging, couldn’t lead this new party. Hazen Argue had taken over the small rump CCF caucus in the House of Commons and with its backing (but against the wishes of the party organizers) was named the national CCF leader.

So, Douglas had to throw his hat into the ring if it meant blocking Argue who, according to Carl Hamilton, the CCF’s national secretary, “was a totally conscienceless man.”

Writing for The Globe and Mail, Walter Gray called Argue “a restless, aggressive man, [he] always seems to be in a hurry, either on the platform or in a quiet conversation. His suits are rumpled, his thick, black hair brushed carelessly back, his black moustache short and bristled.”

Douglas waited only a month before the founding convention of the new party to announce his intentions to run after he received letters of advice from his Saskatchewan cabinet. All but two had suggested he make the jump to federal politics.

It wasn’t much of a fair fight. At the convention — which narrowly settled on the name “New Democratic Party” over the “New Party”, while “Social Democratic Party” and “Canadian Democratic Party” were less popular — Douglas was the conquering hero from Saskatchewan who had put the CCF into power and proven it could govern responsibly. Argue had his small caucus behind him, but not much else.

When the voting was finished, Douglas had the support of 1,391 delegates to just 380 for Argue, representing 78.5% of ballots cast.

Argue was crushed, but said that “no matter what my role in the years ahead, I shall speak for you, I shall work for you, I shall never let you down.” Six months later, Argue crossed the floor to the Liberals.

While Douglas would not bring the New Democrats to new heights — he never won more than 22 seats, while Coldwell had beaten that mark as leader of the CCF in 1945, 1953 and 1957 — he would leave his mark on federal politics, particularly during the Pearson minority governments.

Argue, meanwhile, has been effectively written out of the history of the New Democratic Party. At NDP headquarters, in the line of portraits of past CCF and NDP leaders one finds M.J. Coldwell and Tommy Douglas next to each other, with no other portrait in between.

1965 Canadian federal election

Pearson fails to win his majority

November 8, 1965

Lester Pearson wasn’t much of a political animal — a brilliant diplomat and a progressive thinker, perhaps. But being prime minister was no fun when it was in a minority parliament in which his hated rival, John Diefenbaker, sat across the aisle.

If there was something that Pearson might have hated more than Diefenbaker (and the feeling was mutual), it might have been campaigning. But the only way to win a majority and be free from the hassle of the Tories and the sanctimonious New Democrats in parliament was to call an election.

On paper (and the polls), a snap election call seemed like a good idea. The Liberals had achieved quite a bit since they had returned to power in 1963, ending Diefenbaker’s tumultuous six-year stint as prime minister. The Canada Pension Plan had been brought in, the country finally got its own flag, national unity was being addressed and a universal healthcare program was on its way.

That was a noble record to run on — and just imagine what more could have been done had Pearson enjoyed a majority in the House of Commons! Plus, Diefenbaker was approaching a decade as leader of the Progressive Conservatives. That party’s internal divisions were well-known and the PCs’ organization was falling apart. Diefenbaker was a polarizing, divisive figure, both inside and outside the party. Better to go while he was still leading the PCs and before he could be replaced by someone more likeable.

So, Pearson finally made the call and set the date for the next election for November 8, 1965. On the ballot would be whether Canada would continue the instability of the last few years — the fault of Diefenbaker and the pesky New Democrats, of course — or if Canadians would back Pearson’s administration and let him set an untroubled course for the next four years.

But there were a few problems with this pitch. Much of the instability of the last few years had been the Liberals’ own fault. Corruption scandals had plagued the Pearson cabinet and many of the central figures were from Quebec. Efforts to smooth-over national unity divisions and recognize the bilingual and “bi-cultural” reality of Canada seemed, to many English Canadians, as pandering.

And Pearson was a reluctant, unenthusiastic campaigner. Not so, Diefenbaker.

Leading his party for a fifth consecutive election campaign, many in the PC ranks considered this to be Diefenbaker’s last ride. His paranoid leadership style and unwillingness to depart had splintered the party, but the campaign focused the minds of Tories and allowed them to put those divisions behind them (at least for now).

In the end, Diefenbaker was always more comfortable in the role of an opposition leader than a prime minister, and he was rejuvenated by the partisan fight. While Pearson spent much of the campaign in Ottawa trying to appear serious and prime ministerial, Diefenbaker was touring the country and speaking to electrified (if aging) crowds. John English, writing in The Worldly Years, said Diefenbaker

“…travelled 36,000 miles and visited 196 towns, villages and hamlets. His train passed through prairie and southern-Ontario towns where tears and cheers came quickly as “Dief the Chief” arrived with hands aloft, standing with [his wife] Olive on the caboose. Not all went well: he jaywalked in Toronto; Conservatives in Taber, Alberta, annoyed him by placing the maple-leaf flag on his car; and in Quebec, when told a young man was “mon fils” [“my son”], greeted the young man with: “Bonjour, Mon-seer Monfils.” But these pratfalls became grist for the legend that the seventy-year-old Diefenbaker was becoming. It was his last hurrah, and a vintage performance.”

Diefenbaker attacked the corruption in Pearson’s cabinet while Tommy Douglas of the NDP warned against giving the Liberals a majority (or, as he put it, a “tranquilizer”). The Liberal campaign had little to excite the electorate. Voters weren’t ready to put Diefenbaker back in office. But they were also uninterested in jumping in line behind Pearson and the Liberals.

The election settled nothing, with the Liberals returned with another minority government, two seats shy of a majority. Only a few ridings across the country changed hands and the net effect was that both the Liberals and the PCs won two more seats than they had captured in 1963. The Liberals’ vote share even dropped, by 1.5 points to 40.2%, far below where the pre-election polls had placed the party.

Quebec had again delivered Pearson his majority, with the PCs winning more seats than the Liberals in the rest of the country. Of the Liberals’ 131 seats, 56 came in Quebec. That was a gain of nine over the last election, but that was due to a drop in support for Social Credit. That party had split between Quebec and the West, with Réal Caouette leading the Ralliement des créditistes in Quebec and Robert Thompson continuing to lead the Social Credit wing in English Canada. Caouette could only retain nine of the 20 seats the Socreds had won in Quebec (under his local leadership) in 1963. Much of the vote he lost went to the New Democrats, with the seats going to the Liberals. But those Liberal gains were offset by losses in Atlantic Canada and the Prairies.

The country was still split, with neither Pearson nor Diefenbaker able to cobble-together a majority for the third consecutive election. The New Democrats had their base, gaining four seats and five percentage points and placing first in British Columbia, while the two wings of Social Credit also took seats and votes off the table in the West and in Quebec.

Something would have to give to break the logjam. Or someone. Among the Liberals’ new recruits in Quebec in the 1965 election was Pierre Trudeau. At the time, few saw him as a potential game-changer for the party. Within three years, he’d be prime minister — and finally win that majority government.

1976 Progressive Conservative leadership

Joe Clark becomes PC leader

February 22, 1976

After three fruitless elections as federal Progressive Conservative leader, Robert Stanfield stepped aside in 1976 and kicked off a leadership race. With Pierre Trudeau’s government now into its third term — and the Liberals in office for over a decade — the prospects looked good for whoever could replace Stanfield in the official opposition leader’s chair.

On February 22, 1976, 5,000 PC delegates made their way to the Ottawa Civic Centre to decide who would take the party forward.

The frontrunner was widely seen as Claude Wagner, a former Quebec Liberal cabinet minister. He had a rival from Quebec in Brian Mulroney, who had loads of experience behind the scenes within the PC Party but none as an elected official.

Less flashy was Joe Clark, an MP from Alberta first elected in 1972. He had worked closely with Stanfield and was seen as coming from the Stanfield wing of the party, which made him one of John Diefenbaker’s enemies. Despite having been removed as leader a decade earlier, Diefenbaker still had sway, representing the stout, “One Nation” brand of conservatism in contrast to Stanfield’s more moderate and open-to-Quebec style.

Like Mulroney, Clark was young and had little experience outside of politics. But he was bilingual and a potential compromise candidate for those who did not want to choose between Wagner or Mulroney.

Another big player was PC MP Flora MacDonald, a trailblazer as the first woman viewed as a serious contender for one of the top two political jobs in the country.

Also on the packed ballot was Alberta MP Jack Horner, former Liberal Paul Hellyer, Ontario MP Sinclair Stevens and four other lesser-known MPs.

When the first round ballots were counted, Wagner was indeed on top with 22.5% of the vote, followed by Mulroney with 15%. Clark managed 12%, while Horner and Hellyer were tied at 10% apiece. MacDonald finished with just 9%, well below expectations, and Stevens with 8%.

Along with a couple of lower-placed finishers, Stevens withdrew at this point to put his support behind Clark, who jumped to 23% on the second ballot, just 5.5 points behind Wagner. Mulroney was now third with 18%, Horner in fourth with 12%, MacDonald in fifth with 10% and Hellyer in sixth, dropping to just 5%.

Only three names would remain on the third ballot. MacDonald endorsed Clark, while Horner and Hellyer (as well as Diefenbaker) threw their vote behind Wagner. The camps were splitting up into the moderates behind Clark and the right-wingers backing Wagner.

On that third ballot, Wagner had 43% to 41% for Clark, as Mulroney lost delegates and dropped to 16%. He was eliminated, but unlike all the other contestants would not give an endorsement to either Clark or Wagner.

By a nearly 2:1 margin, Clark picked up the liberated delegates on the fourth and final ballot, capturing 1,187 votes to Wagner’s 1,122 — a margin of just under three percentage points.

Clark, seen as a “darkhorse”, had pulled off the come-from-behind, compromise-candidate victory that would be a path followed by other future leaders like Dalton McGuinty in Ontario or Stéphane Dion for the federal Liberals.

But Clark remained largely unknown, prompting the Toronto Star to headline the next morning’s paper “Joe Who?”

Three years later, though, Clark would eke out a minority victory over Trudeau’s Liberals in the 1979 federal election. His time in office would be short, as he subsequently lost the 1980 election and would face off against Mulroney again in the 1983 leadership race But this time it would be Mulroney who would come from behind — and finish on top.

1993 Canadian federal election

The election that changed everything

October 25, 1993

Heading into 1993, it was clear that Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives were going to have a rough year. But no one would have guessed just how rough things were going to get.

The clock was ticking on Mulroney’s second term as prime minister. Normally, an election would have been held in the fall of 1992, four years after the 1988 election that the PCs had won over the issue of free trade. Instead, a referendum on the Charlottetown Accord was held that October. The defeat of the accord, following a few years after the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, signalled that Canadians were done with constitutional debate — and done with Mulroney.

He and his PC government were incredibly unpopular. The party was polling under 20% and Mulroney’s own approval ratings had dipped to a record-low 12%. Not only had Mulroney spent his last remaining political capital on two futile attempts to bring Quebec into the constitution, but the economy was in the pits, the deficit was soaring and Canadians were smarting at the imposition of the GST.

The PCs had lost a lot of ground to the Liberals, but worse for the party was the splintering of the electoral coalition that had won them their landslide victory in 1984. Buoyed by Western grievances, the government’s support for the Charlottetown Accord and Mulroney’s profligate spending, the Reform Party was making inroads in Western Canada. Led by Preston Manning, son of the former Alberta Social Credit premier Ernest Manning, the populist, conservative Reform Party was eating away at the PCs’ traditional support in the west, as well as in rural Ontario.

In Quebec, the constitutional wrangles had led to the creation of the Bloc Québécois, led by former PC cabinet minister Lucien Bouchard and bringing together a small group of disgruntled PC and Liberal Quebec MPs. With support for sovereignty cresting to 60% in the wake of the failure of Meech, the Bloc was well-positioned to take advantage of the discontent within Quebec. Byelection victories by Reform and the Bloc in 1989 and 1990 indicated that these parties were not just polling mirages.

Faced with no chance of re-election, Mulroney resigned in February 1993. Whoever his replacement would be would have little time to turn the ship around before the election that had to be held in the fall.

Not surprisingly, there were few takers for this job. The big names around the cabinet table — all of whom would find themselves out of work in a few months — withdrew their names from the running, leaving B.C.’s Kim Campbell, a cabinet minister and rising star in the party, as the heir apparent. Jean Charest, a young minister from Quebec, threw his name into the ring to make a race out of it, which he subsequently did. Campbell prevailed, but not by much.

The arrival of a new face at the helm of the government, and the first (and to date only) woman to become prime minister, resulted in a surge in support for the Progressive Conservatives. Suddenly, the party was running even with the Liberals.

Under the leadership of Jean Chrétien, the Liberals were still licking their wounds from the catastrophic defeats of 1984 and 1988. Chrétien wasn’t particularly popular at a personal level — he soon fell behind Campbell in the polls — and lacked support in his home province due to his staunch opposition to the Meech Lake Accord. Quebec had been the backbone of Pierre Trudeau’s election victories, but a breakthrough under Chrétien with the Bloc now on the scene seemed like a longshot. The Liberals would need to beat the PCs in the rest of the country to win.

There was also a new leader at the helm of the New Democrats. The party’s support had risen as the PCs faltered, with polls in the early 1990s showing the NDP competitive with the other parties nationwide. Victories at the provincial level in Ontario in 1990 and in Saskatchewan and British Columbia in 1991 hinted at an orange wave sweeping the country. The new federal leader, Audrey McLaughlin, had made history when she became the first woman to lead a major national party — but by 1993 the NDP was suffering from the unpopularity of those provincial governments, particularly Bob Rae’s in Ontario and Mike Harcourt’s in B.C. The rise of Reform also chipped away at the NDP’s Prairie populist support. Unlike Reform, the NDP had sided with the other parties in favour of the Charlottetown Accord, which was rejected by solid majorities throughout Western Canada.

The election was officially kicked off at the beginning of September, and polls during the first week put the PCs and Liberals tied in the mid-30s in support. Reform and the Bloc had about 10% apiece, with the NDP just below that.

Campbell’s campaign got off to a rough start in her opening remarks and there were to be other gaffes, including the infamous “an election is no time to discuss serious issues” quote (which she did not exactly say).

Meanwhile, the Liberals presented their “Red Book”, a detailed platform document that presented Chrétien and the Liberals as the party with a plan for the future.

By the end of September, the PCs were starting to bleed support to the other parties. They had dropped below 30%, with Reform and the Bloc benefiting most. A five-person debate did not change the trend.

But perhaps accelerating those trends were the ads produced by the Progressive Conservatives that attacked Chrétien, presenting images of the Liberal leader’s face while asking if “this is a prime minister”.

Chrétien, who had a facial deformity due to Bell’s palsy, blasted the ads, saying “it’s true that I speak on one side of my mouth, I’m not a Tory, I don’t speak on both sides of my mouth.” PC candidates apologized for it, as did Campbell, who had the ad pulled.

The wheels were coming off the PC campaign as voters reverted to their pre-Campbell mood. Quebec nationalists had been lost to the Bloc and weren’t coming back. Social conservatives in Western Canada and rural Ontario were flocking to Reform, the PCs’ economic message failing to resonate when the party’s record on the economy was so poor. The NDP was also being squeezed out, bleeding support to Reform in the West and to the Liberals elsewhere.

By the end of the campaign, the polls were showing just how much the PC vote had collapsed. The party was under 20%, running neck-and-neck with Reform. The Bloc had risen to 50% in the polls in Quebec and the Liberals had finally ticked up nationally to the 40% range that was required for a majority government. The years of rage with the Mulroney PCs, the regional grievances of the West and Quebec and Campbell’s poor campaign had all come together to produce one of the most dramatic election nights in Canadian history.

The defeat was like nothing that had ever been seen in Canada — or even in the world of Western democracies. The PCs went from 169 seats and 43% of the vote in 1988 to just 16% and two seats: Jean Charest’s in Sherbrooke and Elsie Wayne’s in Saint John. Only in Atlantic Canada did the PCs manage to clear the bar of 20%.

The Liberals won 177 seats, a gain of 94, and captured 41.3% of the vote. They won 98 of 99 seats in Ontario and 31 of 32 seats in Atlantic Canada, enough to put the party just 19 seats shy of a majority government. Quebec, where the Liberals managed exactly 19 seats, did the rest. Wins in Western Canada, including a plurality of the vote in Saskatchewan, cushioned Chrétien’s majority.

The Bloc managed 49% of the vote in Quebec and won 54 seats, giving it official opposition status and cementing the next few years as ones that would be dominated by national unity issues. In two years, Quebec would hold its second referendum.

Reform, which ran no candidates in Quebec, emerged with 52 seats, all but two of them in the three western-most provinces. Reform won just over half of the vote in Alberta and placed first in British Columbia.

It was there that the NDP suffered most at the hands of the Reform Party, falling 17 seats to just two in the province. The party’s caucus in Saskatchewan was cut in half and all 10 of their seats in Ontario were lost. The NDP was left with just nine seats and 6.9% of the vote.

The political landscape of Canada had been utterly transformed. The PCs ceased to be a major force and would eventual merge itself with (and be largely subsumed into) the Canadian Alliance, the successors to Reform. The presence of the Bloc would forever change the dynamics of elections in Quebec, while the NDP would struggle to regain the footing it once had in Western Canada.

Chrétien would govern for the next 10 years and Bouchard would go on to become Quebec premier after the victory of the NON side in the 1995 referendum. Manning would become official opposition leader after the 1997 election. Leading their respective parties to their worst results ever, however, cost both McLaughlin and Campbell their leaderships.

When talking about modern Canadian politics, the 1993 election is still the main point at which there is a before and an after — and the reverberations of this campaign can still be felt straight through to today.

2002 Canadian Alliance leadership

Stephen Harper’s first big win

March 20, 2002

Once touted as the great hope of the right, the Stockwell Day bubble popped very quickly during the 2000 federal election campaign.

Gaffe-prone and an easy target for the Liberals for his previously-stated creationist views, Day led the Canadian Alliance — the successor to the Reform Party created by Preston Manning, whom Day defeated for the leadership of the Alliance in 2000 — to another second-place showing. Though the Alliance won 66 seats, more than Reform ever did, he failed to make any significant gains in Ontario.

It wasn’t long after this disappointment that the knives came out for Day. Within a few months, 13 MPs in his caucus called for his resignation and were booted from the party. While about half of them were eventually welcomed back into the fold, the others formed the Democratic Representative Caucus, working in tandem with the Joe Clark-led Progressive Conservatives.

Divided, broke and polling poorly, the Alliance was in rough shape. The internal dissent became too much, and a leadership vote was called in mid-2001, to be held on March 20, 2002. While he was coy at first, Day eventually announced he would stand again for the leadership of the party.

A former cabinet minister in Ralph Klein’s Alberta government, Day had limited support within his own caucus to stay on as leader, and as the campaign heated up he intimated that those who opposed him would have little future ahead of them in the Alliance should he be re-elected.

There were a lot of them, and they looked to a former MP as their saviour.

Stephen Harper had once been the Reform Party’s heir apparent to Preston Manning, and was one of the 52 Reform MPs elected in 1993. But he soon chafed under Manning’s leadership and opted not to run for re-election in 1997. Instead, he became the president of the right-wing, small-government National Citizens Coalition. The job kept him in the spotlight, as did a spot as a pundit on Don Newman’s CBC Politics show.

Seen as a good communicator, a fiscal conservative and someone who could expand the party’s appeal beyond it’s Western, social-conservative base, Harper became the main challenger to Day’s leadership. Much of the pre-existing base of Alliance members backed him, and by the end of the leadership campaign so did about half of the Alliance’s remaining MPs.

Harper spent the campaign making Day’s leadership the ballot box question, in one debate saying that “the party has the choice of picking the current leadership, of reliving the current problems and reliving the events of last summer and, frankly, of being stuck with its current support levels. Or it has the option of picking new leadership and getting back on track.”

Day snapped back that “[many MPs] still wonder why you quit and left the caucus in the lurch and left Preston Manning very vulnerable.”

Harper ruffled some feathers for his criticisms of the direction the Alliance had taken under Day, that it had become viewed as a social conservative party in hock to anti-abortionists and the Christian right. Harper felt that this limited the party’s potential appeal, urging a more libertarian, hands-off approach to these contentious issues.

Though Harper and Day were the two front runners, there were two other candidates in the race: Diane Ablonczy and Grant Hill. Both were Reform MPs from Alberta elected in 1993, and both ran on a ‘unity’ platform, arguing for closer cooperation with the Progressive Conservatives. Both Day and Harper avoided the topic as best they could however, with Harper saying he wouldn’t consider a merger with the PCs while Joe Clark was at the helm.

When the deadline for eligibility to vote passed, the Canadian Alliance’s membership had grown to 123,000 — though that was down sharply from the 205,000 members who had signed up for the leadership contest that selected Day in 2000. With backing from well-organized religious groups, Day was able to sign-up the most new members, perhaps twice as many as Harper’s team managed. But Harper had the backing of most of the 70,000 members who were with the party when the contest had started.

Expectations were high that the leadership would not be settled on the first ballot, requiring a second ballot between the two front runners that would be decided two weeks after the results of the mail-in ballot was announced on March 20. The betting money was on Harper having the advantage if it went to a second ballot, as Day was unlikely to get much support from those who backed Ablonczy or Hill.

But a few weeks before the results were announced, one source within Harper’s team told Brian Laghi of The Globe and Mail that their own tracking had Harper with over 50% support and Day somewhere around 30%. It turned out to be a prescient estimate.

The results were announced at an event in Calgary but rumours quickly leaked out about who had won. It was Stephen Harper, who easily cleared the majority threshold with 55% support among the 88,000 members who cast a ballot. He had big support in the one-member, one-vote race in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, while Day was only able to win in Saskatchewan, Quebec and Prince Edward Island.

That cooperating with the PCs had been shunted aside as a campaign issue was shown by the performance of Ablonczy and Hill, who each took less than 4% of ballots cast.

“You have just voted to move our party forward into the future,” Harper told the convention-goers after his win. “Now I ask you … to join me in rebuilding this party and to bring together all who share our values and our vision: Reformers, like-minded PCs and others, regardless of their previous political affiliation.”

It didn’t sound like Harper was contemplating a merger with the PCs. He called the Canadian Alliance “a permanent political institution [that] is here to stay”.

Stung by the defeat, Day called for party unity within the Alliance under Harper’s leadership. He stayed on as an MP and would later serve in Harper’s cabinet once the Conservatives, the product of the 2003 merger between the Alliance and the PCs then led by Peter MacKay, formed government in 2006.

2003 NDP leadership

Jack Layton wins the NDP leadership

January 25, 2003

In the early years of the 21st century, the best days for the New Democrats seemed to be behind them.

Ed Broadbent had brought the NDP to new heights in the 1980s and, for a brief moment, the party was even leading in the polls nationwide. But the 1990s proved to be tough for the New Democrats. The Liberals under Jean Chrétien enjoyed a big majority in the House of Commons and, with the exception of a small uptick in 1997 under Alexa McDonough, the party’s caucus for much of the Chrétien years could squeeze into a couple of minivans.

Unable to make any headway, McDonough resigned her leadership in June 2002 after securing just 13 seats and 8.5% of the vote in her last election as leader in 2000.

The New Democrats were simply unable to find some space on the evolving political spectrum of Canada at the time. The rise of the Reform Party had squeezed the NDP out of its Western strongholds. The Chrétien Liberals’ dominance of Ontario made that province tough going. The party was still nowhere in Quebec. McDonough had made the NDP relevant in Atlantic Canada, but that was unlikely to outlast her.

The first person to put his name forward to take on the task of moving the party forward was Bill Blaikie, MP for Winnipeg–Transcona since 1979. He had experienced the dizzying highs of the Broadbent years as well as the lows of the Chrétien era. He was well-respected, had strength in Manitoba where the party had formed government in 1999 and was a familiar sort of New Democrat, echoing the social gospel, Prairie populism of past NDP and CCF heroes like Tommy Douglas and M.J. Coldwell.

Policy Options described Blaikie as “a bear of a man: tall, bulky and bearded. He rejects the politics of image-making, and is running for the leadership of the New Democratic Party on the basis of his years in the House of Commons as a representative of the underprivileged, and the underrepresented: a defiant voice of moral indignation and moral values.”

In the weeks that followed, other names came forward.

There was Pierre Ducasse, a Quebec NDP activist who gave the party a glimmer of hope that maybe they could make a breakthrough in Quebec.

Bev Meslo, a feminist from Vancouver, came forward as the candidate of the socialist caucus.

Lorne Nystrom also made a bid, of course. A perennial candidate who finished third in both the 1975 and 1995 NDP leadership contests, Nystrom had been a Saskatchewan MP since 1968 (with the exception of one term after 1993). Fluently bilingual, Nystrom would be the centrist candidate — and often dismissed as yesterday’s man.

Joe Comartin, the MP for Windsor–St. Clair, also jumped into the ring.

But the name that garnered the most attention was probably that of Jack Layton, a well-known Toronto city councillor.

For New Democrats who were looking to the future, Layton held lots of promise. He could reach out to urban progressives in a way someone like Blaikie never could. Born in Quebec and able to speak a rough but disarming French, Layton’s candidacy raised hopes that maybe, one day, the NDP could have some influence in that province. He didn’t have a seat in the House of Commons, that was true, but he knew how to get the media to pay attention to him — the kind of attention the NDP desperately needed. Though identified with the left of the party, Layton carried less of the baggage of the NDP’s historical internecine fighting between principle and pragmatism. Layton pitched both.

It was a persuasive argument for some New Democrats. For others, the glitz and glam sounded a lot like what Stockwell Day brought to the table for the Canadian Alliance, with disastrous consequences.

Layton’s campaign got a big boost when he landed the endorsement of Broadbent in November 2002. It wasn’t an easy call for Broadbent, who sat with Blaikie in parliament throughout the 1980s.

“But in deciding who should be leader of the party,” he said at the news conference announcing his endorsement, “you set aside loyalty, you set aside friendship, and that’s difficult to do, frankly … I had other personal considerations, but the political result was very clear in my mind. Jack, in my view, is the best candidate.”

Though the race had six contestants, it was widely seen as a contest between Layton and Blaikie — the modern vs. the old, the upstart vs. the establishment.

The Globe and Mail’s Kim Lunman contrasted the two:

“Mr. Layton, 52, is a well-known civic politician who recently posed on the cover of Toronto's weekly newsmagazine Now sporting a fake tattoo on his arm emblazoned with the name of his wife, Olivia Chow. Members of the band Barenaked Ladies were among the first group to endorse his candidacy.

“An avid cyclist who plays the piano, Mr. Layton schmoozed party members at martini parties during his campaign. He even tickled the ivories at the Jazz Bassment in Saskatoon, singing: ‘Hit the road Paul [Martin], and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.’

“Mr. Blaikie, 51, has been a familiar face in Parliament since … 1979. At the time, he was a 27-year-old United Church minister. He was told he'd never win a seat and he ignored suggestions that he should shave off his beard. The father of four, married to Brenda Bihun, has continued to keep his facial hair, agreeing to only one makeover tip, from his optometrist: a new pair of eyeglasses.

“Mr. Blaikie also has a musical side. He plays the bagpipes.”

Though the campaign was hardly nasty, Blaikie did criticize Layton’s inexperience and bristled at the comparisons between him and his chief rival.

“I think people's general frustration with the NDP [has] been projected on to me and they're projecting fantasies of something new on to Jack," he said. “I'm not anybody's fantasy. I'm a known commodity.”

The polls and the pundits pegged the race as very close. Blaikie had the caucus behind him, but Layton had Broadbent, more money and had signed up the most members. Talk of an Anybody-But-Layton campaign in the days before the voting suggested it could come down to the wire and members’ second choices.

In the end, though, it wasn’t all that close. The delegates at the National Trade Centre at Exhibition Place in Toronto, about a thousand or so, got a shock when the results of the nearly 44,000 votes were tabulated.

Rather than going to multiple ballots, Layton won on the first with 53.5% support. Blaikie was far back with just 24.7%.

No other candidate hit double-digits. Nystrom took 9.3%, Comartin 7.7%, Ducasse 3.7% and Meslo 1.1%. Layton had won a majority of ballots cast by both party members and labour delegates, whose votes carried extra weight in the count.

It even took the Layton campaign by surprise, as there were reports in the Toronto Star that, prior to the result being announced, Layton’s team was “shuttling ‘Jack’ armbands to the Ducasse and Comartin camps to be at the ready for those supporters who wanted to change sides on a second ballot.”

The scale of his victory, perhaps, made it easier for the contenders to stick together. Despite the blow, Blaikie would run again under Layton and be re-elected in 2004 and 2006 before making the jump to provincial politics. His son, Daniel, is now the NDP MP for Elmwood–Transcona.

Nystrom would run for re-election once more in 2004, but go down to defeat against a little-known Conservative candidate named Andrew Scheer.

Comartin would stick with Layton throughout the rest of his career, being one of the few NDP MPs with long experience in parliament when the party rose to official opposition status in 2011. He retired before the 2015 election.

That sense of timing didn’t belong to Ducasse, though, as he unsuccessfully ran for the NDP in Quebec in 2004, 2006 and 2008 before deciding not to run again in 2011.

That election, the pinnacle of Jack Layton’s political career, was still more than eight years in the future in January 2003. In the short term, Layton would make some modest progress for the New Democrats in the 2004 election, lifting the party to 19 seats, including his own in Toronto–Danforth, and 16% of the vote. The NDP would see more growth in 2006 and again in 2008, when the NDP was back to its strength of the Broadbent era. The party seemed stuck there, though, until the 2011 campaign began. The next few months would prove to have some magic, and tragedy, for Jack Layton and the NDP.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Canada, the Library of Parliament and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Dynasties & Interludes: Past and Present in Canadian Electoral Politics, by Lawrence Leduc and Jon H. Pammett

Turning Points: The Campaigns that Changed Canada, 2004 and Before, by Ray Argyle

Nation Maker: John A. Macdonald, His Life, Our Times, by Richard Gwyn

Alexander Mackenzie, by Dale C. Thomson

Wilfrid Laurier: Quand la politique devient passion, by Réal Bélanger

Robert Laird Borden: A Biography, Volume 1, by Robert Craig Brown

In Search of R.B. Bennett, by P.B. Waite

The Life and Times of Tommy Douglas, by Walter Stewart

M.J.: The Life and Times of M.J. Coldwell, by Walter Stewart

Rogue Tory: The Life and Legend of John G. Diefenbaker, by Denis Smith

The Worldly Years: The Life of Lester Pearson, 1949-1972, by John English

Réal Caouette: L’homme et le phénomène, by Marcel Huguet

The Longer I'm Prime Minister: Stephen Harper and Canada, 2006-, by Paul Wells

Joseph Howe, Volume II: The Briton Becomes Canadian, 1848-1873, by Murray Beck