#EveryElectionProject: British Columbia

Capsules on British Columbia's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about B.C.’s elections and leadership races.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1907 British Columbia election

Richard McBride wins again

February 2, 1907

Partisan politics (or, at least, officially partisan politics) was still a novelty in British Columbia when voters went to the polls on February 2, 1907. It was only the second campaign run along party lines after Richard McBride, who became premier in June 1903, announced his government would be a Conservative government, and promptly won an electoral mandate as a B.C. Conservative later that year.

By the end of 1906, McBride was ready to call another election, which he announced on Christmas Eve.

The campaign would be centred around the issue of “Better Terms” for British Columbians in Confederation, along with securing continued economic development for B.C. and increased immigration — white immigration, preferably from Great Britain. At the time, Chinese, Japanese and South Asian Canadians in B.C. could not vote, and both the Conservatives and Liberals were keen to keep it that way.

J. A. Macdonald, the Liberal leader, tried to make hay of the whiff of scandal that surrounded some members of the McBride government, but was unable to make headway.

McBride, touring the province during a notably chilly winter, kept the focus on getting Better Terms, claiming that if the Liberals were elected it would send the message to the provinces in the east that British Columbians weren’t serious about their demands.

The Liberals, of course, said they were for Better Terms, too, but that McBride had mishandled relations with the federal (Liberal) government.

It was an ugly campaign, with charges of dirty tricks coming from both sides, plenty of anti-French and anti-Catholic rhetoric along with fearmongering that either McBride would bring in more Asian labourers or Macdonald would enfranchise Japanese Canadians.

On election day (in which the Conservatives were offering voters the wonder of automobile rides to the polls in Vancouver), McBride won the solid victory he had failed to achieve in 1903.

His party won 49% of the vote and 26 seats, a gain of four seats since the last election. The Liberals dropped to 37% of the vote and 13 seats, while the Socialists and Labour combined for around 13% of the vote and three seats. In all, McBride’s government went from a slim majority of 22 seats in a 42-seat legislature, to a reliable majority of 26.

McBride would win a bigger landslide in 1909 (which would prompt some rumblings that the successful B.C. premier could make a great replacement for the twice-beaten Robert Borden as federal Conservative leader) and his greatest victory in 1912, before stepping down as premier in 1915.

1916 British Columbia election

The defeat of Bowserism

September 14, 1916

The early years of the 20th century were prosperous ones for British Columbia. After coming to power at the head of the Conservatives in 1903, Richard McBride presided over a period of growth and economic development in the province, all the while standing up for ‘Better Terms’ for B.C. from the Liberal government in Ottawa. For his efforts, McBride secured huge election wins in 1909 and 1912.

But by 1915, the McBride government was staggering. Violent labour strikes on Vancouver Island in 1914 had to be put down by the militia and McBride’s Conservatives, scandal-ridden and corrupt, were now leading a province that had been driven deep into debt.

Epitomizing the premier’s grandstanding as well as his profligate recklessness was McBride’s decision to purchase two submarines for British Columbia at the outset of the Great War in order to protect the West Coast from German marauders.

(Yes, for a short time before the federal government reluctantly stepped in, British Columbia had a navy.)

Faced with internal dissent and growing unpopularity, McBride resigned in December 1915 and finally made way for William John Bowser.

Bowser had been McBride’s right-hand man (and eventual rival) in office, acting as premier during McBride’s frequent trips to Ottawa. Bowser was a ruthless politician with a well-oiled political machine in Vancouver that relied on patronage, bribery and “the occasional threat” to deliver big majorities for the Conservative Party. What he didn’t have was McBride’s charisma.

He was dealt an early blow shortly after coming to power when some of his new cabinet appointees were defeated in byelections by the Liberals, a party that had been left seatless in the 1912 provincial election. One of those defeats came at the hands of Liberal leader Harlan Carey Brewster, who ran in the seat vacated by McBride, now the province’s agent-general in London.

Brewster, who had been named leader of the Liberals at a convention in Revelstoke in 1913, supported prohibition and female suffrage, both of which would be put to a referendum in the 1916 election. He pledged aid for the agricultural sector and free land for settlers in B.C.

When the election was finally set for September 14, 1916, Brewster went on the attack against the McBride-Bowser government over its land policies, mismanagement of the over-budget (and questionable) Pacific & Great Eastern Railway and Bowser’s own conflicts of interest.

Brewster had a ready audience in British Columbians who were tired of the Conservative government. According to the Liberal-leaning Globe correspondent in Vancouver,

“Unquestionably much good legislation was passed, but the good things were offset by special “fake” measures, and even vicious precedents which were designed for purposes of political expediency. For instance, good legislation like the prohibition act, the shipbuilding scheme, woman suffrage and the workmen’s compensation act has been more than discounted by the Government’s extravagance in dealing with the Pacific & Great Eastern Railway, and in providing a salary for the office of Agent-General in London larger than that paid to the Lord High Commissioner of Canada.”

Simply put, the election was a change election. The Conservatives had been in power for too long and were seen as incompetent, tyrannical and corrupt. By comparison, Brewster and the Liberals appeared to be eager reformers ready to take over and defeat a premier who might have been able to twist an arm or two but was unable to charm the electorate.

In the words of one Conservative candidate, “unlike Sir Richard McBride, Mr. Bowser was … not versed in all those arts of vote getting of which Sir Richard was a past master.”

The result was a huge victory for the Liberals. From being shutout in 1912, the Liberals won 36 seats and captured 50 per cent of the vote, an increase of nearly 25 percentage points since the previous election. It was, according to the Victoria Times newspaper, a victory over “Bowserism, the party machine and the patronage system.”

The Conservatives were reduced to just nine seats and 40.5% of the vote, down 19 points from 1912. Bowser’s Vancouver machine had finally faltered — the Conservatives won only one of six seats up for grabs in the city and were relegated to ridings largely in the B.C. Interior.

An Independent and Independent Socialist were also elected on Vancouver Island, while the Socialist Party — which took 11% of the vote in 1912 — lost much of its support to the Liberals.

Despite the resounding defeat, Bowser delayed his resignation for another two months in order to wait for all of the soldiers’ votes to come in from overseas, votes that just happened to be overseen by the B.C.’s agent-general in London, Richard McBride.

Those votes didn’t overturn the results (though they did save Bowser in his own seat), but they did overturn the results of the Prohibition referendum. It had been supported by voters in British Columbia, but the soldiers fighting in the trenches voted against it by a margin of four-to-one.

There were, however, accusations of irregularities — including officers buying soldiers’ votes with booze. Brewster, a prohibitionist, struck a commission to investigate the allegations. The commission suggested tossing out those votes, and prohibition went ahead.

Also going ahead was women’s suffrage, which had been supported by about 70% of the (male) voting electorate in the referendum.

For the Conservatives, 1916 proved to be nearly the end of the party. It would only return to power for one term in 1928 before being defeated in the midst of the Great Depression. After playing a minor role in some post-WWII coalitions with the Liberals, the B.C. Conservatives would never get another sniff of power again.

1928 British Columbia election

Prosperity now, Depression later

July 18, 1928

The Roaring Twenties didn’t roar for everyone equally, and that included British Columbians. A depression in the early part of the decade had kept B.C. behind some other jurisdictions, but by the end of the 1920s the province finally appeared to be catching up, with opportunities abounding.

For the governing B.C. Liberal Party, it should have been easy sailing. But their popular leader, John Oliver, died of cancer in 1927 after nearly a decade in office. He was replaced by John Duncan MacLean, the finance minister.

With less than a year as premier under his belt, MacLean set the next election for July 18, 1928. He would run on his record — well, Oliver’s record. During his short time in office, MacLean hadn’t introduced anything new or particularly forward-looking. He pitched reduced taxes, a resolution to the vexing (and costly) Pacific Great Eastern Railway issue and a hard line against the immigration of Chinese and Japanese nationals into B.C. MacLean wanted the proportion of Asian immigrants in his province to be the same as that of Canadians in China and Japan.

But the foundation of his future re-election strategy was the past. The party published a pamphlet entitled What Liberalism Has Done for the Masses, which was little more than a list of things that had been accomplished during the Oliver years. Hoping that continuity would be enough, MacLean kicked off his campaign on June 8 in Abbotsford.

The Conservatives, though, couldn’t get going so quickly. Their leader had to first make his way home from Ottawa.

Simon Fraser Tolmie had been named the leader of the B.C. Conservatives in 1926, taking over from the polarizing figure of William John Bowser (who was so polarizing, in fact, that renegade Conservatives opposed to him ran and won seats under the Provincial Party banner in 1924). Tolmie was a Conservative MP at the time and had been since 1917, with some experience as a minister under both prime ministers Robert Borden and Arthur Meighen.

“Loyal, affable and tactful, Tolmie avoided controversy in his portfolio, leaving the actual day-to-day routine to his deputy,” writes William Rayner in British Columbia’s Premiers in Profile. “The portly, effusive minister preferred to glad-hand his way from county fair to county fair.”

Tolmie didn’t give up his day job when he reluctantly took over the divided B.C. Conservatives, but he did resign his seat when MacLean called the election. He jumped on a train and made his way across the country. It was nearly a week after MacLean’s first speech in Abbotsford that Tolmie launched his campaign in Victoria.

While MacLean promised continuity and stability, Tolmie promised prosperity for all. Unlike the former schoolteacher that was MacLean, Tolmie was a folksy retail politician, who used farm analogies drawn from his experience as a veterinarian and farmer. Under Tolmie and the Conservatives, British Columbia would have a bright future and a bustling economy. Most importantly, it would have change.

There just wasn’t much of substance separating the two offers of the Liberals and Conservatives, beyond a fresh face and a sunnier disposition. The Liberals tried to belittle Tolmie, with Duff Pattullo, a Liberal minister and future premier, saying the Conservatives “were sitting in the shades of Opposition” and so “cannot see the sunshine enjoyed by the great masses of the people of British Columbia.”

The great masses, though, weren’t feeling that warmth for the Liberals. Though MacLean telegrammed campaign workers two days before election day to say that “reports from all over the province indicate a sweeping victory”, other Liberals weren’t so sure. One party organizer warned Mackenzie King, the Liberal prime minister in Ottawa, that he’d be best to stay away from the campaign as the provincial party had become a liability.

The warning was prescient. The Liberals lost 13 seats as support for the Conservatives soared by 24 points to 53.3%, delivering 18 more seats to the party. Tolmie had a majority with 35, the Liberals with just 12.

The Conservatives had broken through into the Lower Mainland, sweeping all six of the seats in Vancouver after they had failed to win a single one in 1924. They repeated their sweep of Victoria, defeated two incumbent candidates from the Independent Labour Party, and won all three of the seats (and most of the votes) that had been won by the Provincial Party in the last campaign.

Only the north, where Pattullo held sway, stuck loyally to the Liberals and MacLean was one of the party stalwarts to go down to defeat.

Tolmie had been elected on a wave of change and a promise of greater prosperity to come — an unfortunately timed pledge to be making in 1928. When the stock market crash came in October 1929, Tolmie’s home-spun wisdom was no match for the ravages of the Great Depression. Public anger and the old divisions within the B.C. Conservatives would do him in, and what was left of his party went down to a catastrophic defeat in 1933. For the B.C. Conservatives, Simon Fraser Tolmie would be the last premier they would ever elect.

1952 British Columbia election

B.C.’s first re-alignment

June 12, 1952

Not every political re-alignment happens in the light of day, with polls forecasting big changes to come in elections to be held months into the future. Some happen quickly and without warning.

Take British Columbia’s re-alignment in 1952, for instance.

Since the province’s inception, only two parties had ever governed it: the Liberals and the Conservatives. And, by 1952, the two parties had even contrived to avoid any of their members sitting on the opposition benches.

After the Liberals won a minority government in the 1941 B.C. election, a coalition was formed between them and the Conservatives. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, predecessor to today’s NDP, had emerged as a real rival to the two old-line parties. Under leader Harold Winch, the CCF had won a third of the vote in 1941 and increased that to 37% and 35% in the 1945 and 1949 elections.

The Liberals and Conservatives, though, had no trouble keeping the socialists at bay thanks to their coalition, winning thumping majorities. But the relationship between the two parties was rarely amical. Herbert Anscomb, leader of the Progressive Conservatives (as they were re-christened) and minister of finance in the coalition government, liked to thumb his nose at the federal Liberals in Ottawa and became increasingly uncooperative with Boss Johnson’s B.C. Liberals. The tensions came to a head in early 1952, and Anscomb was dismissed from cabinet. He took his Conservatives with him, and the coalition was over.

The Liberals had good reason to look ahead to the next election with some confidence. They had won enough seats in 1949 to form a government of their own, and the province was largely in good shape. The economy was picking up, wages were high and unemployment was low. But voters were getting tired of the political games in Victoria that the bickering coalition partners had played over the previous years.

Maybe the CCF would take advantage. Surely it wouldn’t be the oddball Social Credit League that took a miniscule share of the vote in 1949.

But the Socreds were suddenly looking viable, thanks to the support of W.A.C. Bennett.

Bennett was an MLA from the Okanagan and a twice-defeated candidate for the Conservative leadership. Seeing his ambitions blocked within the provincial party, Bennett quit the coalition and sat as an Independent, pondering the launch of his own rival party. In the end, he plumped to join Social Credit, “hook, line and sinker”.

He didn’t have much time for Social Credit’s weird monetary theories, but he did respect the work that Ernest Manning had done in Alberta as leader of a Social Credit government there. Maybe he could hitch his wagon to the movement and take it to power.

His involvement with the party gave it new energy, and membership of the B.C. Social Credit League had grown from about 500 members in 1950 to more than 8,000 in 1952. In his last speech in the legislature before it was dissolved for the 1952 election, Bennett was howled down and heckled by his former coalition colleagues. They particularly didn’t like his prediction that Social Credit would form the next government and that the Liberals and Tories “won’t be back for fifty years”.

While the Socreds’ most well-known and charismatic figure, Bennett was not the party’s leader. He didn’t have the backing of the Alberta Socreds, who held a lot of influence within the B.C. wing of the party. They still wanted to call the shots from Edmonton and provided its provincial off-shoot with funds and campaign expertise. Sensing that the B.C. Socreds needed the help, Bennett withdrew his name from a leadership vote and allowed Ernest Hansell, an Alberta Socred MP, to be named campaign leader. The party leader would be named after the election.

That Hansell, described by a journalist as “a short, middle-aged man, with a loud tie, a mouth that creased down at the corners and a permanent five o’clock shadow”, was only a campaign and not a party leader was attacked by both Johnson and Anscomb, the PC leader calling the B.C. Socreds “the headless brigade from over the mountains”.

It wouldn’t, though, be a major issue for voters. Instead, it was the record of the coalition government that was on trial. Both the Liberals and the PCs tried to take sole credit for anything good they had done and blame the other for anything voters didn’t like, which muddled their messaging. One of those things they didn’t like was the B.C. Hospital Insurance Service, a compulsory health insurance program. Running a big deficit, the BCHIS increased premiums and charged co-insurance fees for hospital stays. The program irritated voters. CCF promised to socialize it. The Socred’s promised to make it non-compulsory.

Another issue was the institution of a new method of voting — a preferential ballot. First pitched by Bennett when he was a Tory MLA, the coalition government adopted the system, asking voters to rank their choices. It was thought that this would work in favour of the Liberals and PCs and avoid a vote-split that could elect the CCF.

But instructions to voters weren’t very clear. The Liberals asked their supporters to rank “1-2 for free enterprise”, not stipulating exactly who #1 or #2 should be. Both the PCs and CCF asked their voters to only rank only their party first and give their second choice to no other party, while the Socreds asked for that first-ballot support but didn’t neglect second choices.

Johnson, Anscomb and Winch waged a campaign against each other, largely ignoring Social Credit. But support for the Socreds, unbeknownst to the established parties, was growing.

David J. Mitchell, writing in W.A.C. Bennett and the Rise of British Columbia, says of the Socred campaign that “most campaign literature came from Alberta and was not directly relevant to British Columbia; however, local Socred brochures were produced, usually simple mimeographs, replete with typographical errors, and so unprofessional looking that they stood in stark contrast to the flash campaign materials of the other parties, which added immensely to the homespun appeal of Social Credit.”

The Socred rallies had a Christian revivalist feel, though the B.C. iteration of the party didn’t lean so heavily toward Christian fundamentalism as did the Alberta version. First and foremost, they promised “free enterprise” and small, clean government, as well as the development of natural resources. That last issue was an important plank for the CCF as well, though Winch wanted more nationalization of British Columbia’s resource sector.

It was only at the end of the campaign that the press and the other parties started to take notice of Social Credit. Johnson and Anscomb attacked them as leaderless and inexperienced, Winch as totalitarian fascists. Hansell had run a low-key campaign and was aided by Premier Manning, who addressed a massive rally. But the real leader of the Socred campaign was Bennett, who toured the Interior and lent his assistance to local candidates.

With such complicated ballots, the counting was slow. When the results of the first count emerged the day after the June 12 voting, the Liberals and PCs were shocked. They were trailing the other parties by a wide margin.

Winch and the CCF had topped the voting, finishing first in 21 ridings. The Socreds were ahead in 14. The Liberals and PCs were ahead in only nine and three seats, respectively. Together, they had won 39 seats in 1949.

Voters were split, though. The CCF had the support of 31% of them, with the Socreds following at 27%, the Liberals at 23.5% and the PCs at 17%. How it would play out was still anyone’s guess, as only five of 48 seats had been settled on the first count. Two of these five were Winch and Bennett, who each secured a majority of the vote in their own ridings. One of them seemed destined to be named premier.

Counters had to re-allocate support according to ranked preference in the 43 other ridings, and the process was long. The second count results were only announced on July 3. It took more than another week for the final result to be known.

On the final count, Social Credit had edged ahead, winning 19 seats to the CCF’s 18. As the ranked ballots were counted, the folly of the coalition parties’ plans became clear. Many of their voters did rank the other party as their second choice, but ultimately the Socreds benefited as the second or third choice of many British Columbians — including CCFers.

The Liberals retained only six seats and the PCs just four, none of them the seats of either Anscomb or Johnson.

Most of the Socreds’ seats were won in the Interior and north, where Bennett had spent much of the campaign, but they also won a handful in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland. The CCF won its seats on Vancouver Island, in Vancouver, Burnaby and New Westminster, as well as in the southern Interior. The Liberals won most of their seats in Victoria, with the PCs winning two of their four in Vancouver. The old parties appeared finished.

On July 15, the Socreds finally got around to choosing their real leader. Hansell, though an Alberta MP, had some notions of becoming B.C. premier, but instead the caucus of 19 MLAs voted en masse for their real leader. W.A.C. Bennett received the votes of 14 MLAs, and was sworn in as premier on August 1, 1952.

Within a year, Bennett would turn his shaky minority into a majority government, and kick-off a long reign of Social Credit rule in British Columbia. From 1952 to 1991, the B.C. Socreds were in power for all but three years. When the last Socred government went down to defeat, it was replaced by the New Democrats — not the Liberals or the Tories.

Bennett’s prediction that the two older parties would be out of government for 50 years turned out to be a good one. He was off by only one year, as the B.C. Liberals’ exile from power ended in 2001, 49 years after the 1952 election. The Conservatives drifted off into irrelevancy. At least, for a time.

1969 B.C. NDP leadership

Berger beats Barrett

April 12, 1969

By early 1969, the Social Credit Party had ruled British Columbia for nearly two decades under the leadership of W.A.C. Bennett, a populist who had successfully brought together the ‘free enterprise’ forces in the province. His last victory, in 1966, marked the fourth consecutive defeat for Robert Strachan, the Scottish-born leader of the B.C. CCF and, later, NDP.

Strachan, more of a centrist than the red-baiting Bennett made him out to be, was leading a divided caucus of New Democrats. He had already seen off a leadership challenge from the left by the young Thomas Berger in 1967. Though it didn’t take him down, the challenge fatally weakened Strachan’s leadership and split the caucus, and he decided to resign as leader in early 1969.

The New Democrats had to get a replacement for Strachan in a hurry. Bennett had already suggested that there would be a campaign in 1969, perhaps as soon as June.

Unsurprisingly, one of the candidates in the running to replace Strachan was Tom Berger. Now 36, this lawyer who specialized in civil rights cases and who had argued in front of the Supreme Court, represented a riding in Vancouver. He was an immediate front runner and the candidate of labour, an increasingly influential presence in the B.C. NDP — and one that was in a near-constant state of warfare with Bennett’s Social Credit government.

The main challenger was a social worker just two years older than Berger, Coquitlam MLA Dave Barrett.

Also in the running were Robert Williams, another 30-something MLA from Vancouver, and John Conway, who at just 25 and a graduate student represented the radical left wing of the party.

The contest, though, was supposed to be primarily between Berger and Barrett. There was some buzz on the Friday before the convention when Strachan, who had worked to keep the unions from becoming too powerful within the NDP, decided to endorse Williams. Suddenly, it appeared there might actually be a third contender who could win it.

Nearly 800 delegates were eligible to vote at the convention, including over a hundred from affiliated trade unions. The results of the first ballot were finally announced late on Saturday night, April 12, 1969.

Berger emerged as the clear leader in the contest, taking just over 46% of the ballots cast. Barrett was far behind at 32%, while Robert Williams took 16.5% of the vote. Conway managed just 6% and was eliminated.

Williams, though, didn’t stick around. He withdrew before the second ballot and threw his support behind Barrett. Strachan went along with him, making it clear the contest was between Berger’s more left-wing vision of the party and Barrett’s more centrist approach.

Williams nearly delivered for Barrett when the results were revealed shortly after midnight. Barrett’s support jumped by 126 votes, representing nearly all of Williams’s delegates. Berger increased by just 47 votes, probably most of them from Conway, but it was just enough. Berger won with 52% of the delegates’ support, beating Barrett by 411 votes to 375.

It was a close result, and Berger tried to paper over the divide.

“It was a good fight, Dave,” he said to his defeated opponent after his victory, “but I’m glad it’s over and we are back on the same side.”

Berger promised New Democrats that the party “is going to govern this province in the 1970s”. He proved prescient. But it wasn’t Berger who would lead the NDP to power for the first time in British Columbia. Bennett had one more victory in him, defeating Berger and the NDP in 1969. That marked the end of Berger’s leadership. But three years later, in 1972 under Dave Barrett, the NDP would finally bring W.A.C. Bennett’s long run in office to an end.

1972 B.C. Liberal leadership

The B.C. Liberals’ chosen one

May 22, 1972

Parties come and parties go in British Columbia’s provincial politics. Once upon a time, the B.C. Liberals dominated on the west coast, and when they faltered the Conservatives would take their place.

That all changed in 1952, when British Columbians rejected both of the older parties and threw their support behind Social Credit and W.A.C. Bennett, who would serve as premier for 20 years.

The B.C. Liberals never got very close to power over those two decades, always winning between two and six seats and maintaining a consistent — but consistently low — level of support between 19% and 24% of ballots cast.

Arthur Laing and Ray Perrault piloted the Liberals through most of those years, but in 1969 the task fell to Pat McGeer. In that election, he led the Liberals to another typical result: five seats, 19% of the popular vote and third-party status in the legislature.

With an election on the horizon in 1972 (W.A.C. Bennett liked to call his elections every three years), there was some grumbling about McGeer’s leadership of the party. A brain researcher, Dr. McGeer decided in May that he couldn’t focus all of his energies on the party and so announced his resignation. His replacement could be chosen at the party convention in Penticton, scheduled to be held less than three weeks later.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the fix was in — that was not long enough to hold a proper leadership race, and McGeer gave a hearty endorsement to David Anderson, the Liberal MP for Esquimalt–Saanich, who just happened to be along side him at his press conference.

An outspoken environmentalist and former officer in the foreign service, Anderson was a 34-year-old first-term MP, elected as a Liberal in the 1968 federal election. He was a backbencher, but had made a name for himself on Vancouver Island for his opposition to a proposed U.S. oil pipeline-tanker route that would run from Alaska down the B.C. coast. He was a thorn in the side of Pierre Trudeau’s government, and it was quipped that the Liberals in Ottawa weren’t sorry to see Anderson try his luck on the other side of the country.

“It is a personality — not a party — that will finally dent the Socred armor here, and Anderson is certainly a personality,” wrote Nick Hills for the Southam News Service. “What has made Mr. Anderson unpopular in Ottawa is that he doesn’t have much time for modesty. He knows he’s good and he acts like he knows he’s good.”

The B.C. Liberals sensed that they needed to shake things up. W.A.C. Bennett and the Socreds were looking tired, but the Liberals had plenty of competition. The NDP had a new leader in Dave Barrett and the Progressive Conservatives, a minor party that ran a single candidate in 1969 and had only two Socred defectors for a caucus, appeared to have some new energy of their own after selecting Derril Warren, younger even than Anderson, as their new leader.

But it wouldn’t be a walk for Anderson. On the same day that McGeer announced his resignation and his endorsement of the Liberal MP, another colourful figure threw his hat into the ring.

Bill Vander Zalm, born in the Netherlands, now mayor of Surrey, had also run for the Trudeau Liberals in 1968 but, unlike Anderson, hadn’t won a seat. If Anderson was the standard-bearer of the left of the B.C. Liberal Party, Vander Zalm would carry the banner of the right. In his convention speech, he targeted the employable who were on welfare and said that drug dealers deserved the lash, while he organized for a “10-girl chorus line parading through the lobby of the convention centre” in Penticton.

There were about 600 attendees at the convention, but it was seen as a foregone conclusion that Anderson, anointed by McGeer as his heir apparent, would prevail.

The result was perhaps not as sweeping as observers expected, but Anderson nevertheless easily beat Vander Zalm, taking 69% of the vote.

The new leader had some challenges ahead of him. While he was well-known in British Columbia for his environmental advocacy, it did give him the veneer of a single-issue candidate. The party was deeply in debt and politically weighed down by the unpopularity of the Trudeau government, which would fall from 16 to just four B.C. seats in the October 1972 federal election.

Bennett, as expected, called an election a few months later. The Socreds would finally go down to defeat in the August vote — but it was the NDP under Dave Barrett that came to power. Anderson led the Liberals to another five-seat election performance and the party’s vote share fell to 16%. It would prove to be the start of a decline for the B.C. Liberals as politics polarized between Social Credit and the New Democrats and the Liberals were squeezed out.

The polarization even swept Bill Vander Zalm along with it. Though he ran as a Liberal under Anderson in 1972, by the next election he was a Socred candidate. In another decade, he’d be a Socred premier. The closest Anderson would get to power was around the federal cabinet — as Jean Chrétien’s minister of the environment.

1973 B.C. Social Credit leadership

Bill Bennett succeeds his father as B.C. Social Credit leader

November 24, 1973

After two decades in office, making him the longest-serving premier in British Columbia’s history, W.A.C. Bennett was defeated in the 1972 provincial election and, for the first time since it became a real political force, the B.C. Social Credit Party was in need of a new leader.

There was a problem, though. Bennett had maintained such a tight, personal control over the government — he served as both premier and finance minister — that he never quite found the time to groom a successor. There was no heir apparent to replace him. In fact, it wasn’t even a given that a replacement for Bennett was of vital importance, as it was an open question whether or not the ‘free enterprise’ forces in B.C. could coalesce around a new party, rather than the somewhat anachronistic Social Credit brand.

But Bennett laid the groundwork for his son to follow in his footsteps, talking about the need for a “young” leader from a new generation to replace him. Before the leadership race could get going, W.A.C. Bennett resigned his South Okanagan seat and his son Bill announced he would run to fill the vacancy. After he won the byelection, this effectively limited the field of potential replacements for W.A.C. Bennett to those with a seat in the legislature, closing the door to outside candidates who might have appreciated the opportunity to run in the former leader’s safe seat.

The good news for Bill Bennett was that his Socred colleagues in the legislature weren’t leadership material — the serious contenders to replace W.A.C. Bennett had been defeated in the 1972 election that brought Dave Barrett’s NDP to power for the first time in B.C. history.

Some 1,500 delegates attended the leadership convention that was held on November 24, 1973 in Vancouver. Many were Bennett supporters, ferried or bussed in from Vancouver Island and the B.C. Interior to ensure a good result for the son of the former premier.

And they got one. On the first ballot, Bill Bennett received 883 votes, beating his nearest rival by a margin of more than 600. His father called in some favours and helped deliver the victory, but Bill Bennett would adamantly try to distance himself from his father’s shadow and, after just three years of NDP government, the Socreds would storm back to power in 1975.

Bill Bennet would win two more elections and serve as premier for nearly 11 years, before he stepped aside and was replaced by Bill Vander Zalm. With the exception of the short Barrett interregnum, the Bennett dynasty governed British Columbia for all but three years from 1952 to 1986.

1979 British Columbia election

B.C.’s politics polarizes even more

May 10, 1979

At the end of a whirlwind three years in office, Dave Barrett’s quick-moving, reforming and often unfocused B.C. NDP government went down to defeat at the hands of Social Credit, which had galvanized the right-of-centre vote behind a familiar name: Bill Bennett, son of former premier W.A.C. Bennett.

The Socreds had succeeded in eating into the Progressive Conservatives’ vote and stealing away the right-wingers that were still backing the B.C. Liberals.

Nearly four years later, Bennett aimed to keep his electoral coalition together.

A day after announcing what his government called a “sunshine budget” “crammed with benefits for every taxpayer”, Bennett pre-empted the television and radio networks to make his announcement. He promised the networks it would take five minutes, but it took him 20 minutes to declare that British Columbians would be going to the polls on May 10, 1979.

That set the date just 12 days before the federal election — a coincidence that worked very well for Bennett’s Social Credit Party. The federal campaign would divide the attention and resources the New Democrats and PCs could dedicate to the provincial battle. Bennett’s party had no such complication.

The central plank of Bennett’s campaign would be the giveaway of five shares of the B.C. Resources Investment Corporation, each worth around $60, to every British Columbian. The BCRIC was a holding company that invested in B.C.’s resource industry, and the government encouraged British Columbians to invest some of their own money, too. It would eventually go bust and people would lose a lot of their investments, but in 1979 it didn’t turn out to be the campaign issue Bennett had hoped it would be — especially after Dave Barrett said that the giveaway was irreversible.

Despite his drubbing at the polls in 1975, Barrett was still leader of the B.C. NDP. He hoped to make a comeback.

The New Democrats had learned their lesson, though. While Barrett ran against the Socred record of austerity measures, he also ran against type: he was calmer, more moderate. He admitted his government had made mistakes and had tried to move too far too quickly.

The NDP had went “from the wilderness into power,” Barrett said. “It’s had a taste of power. It doesn’t like the wilderness any more. The party is more realistic. I’m more realistic.”

The move to the centre was part of a broader drift in B.C. politics. The PCs and Liberals had been decimated over the last few elections, and with the Liberals running only a handful of candidates the NDP targeted their remaining voters, especially those that could swing results in the suburbs around Victoria and Vancouver.

Bennett, whose style The Globe and Mail’s John Clarke called “heavy, sometimes inarticulate and generally humorless”, attacked the record of the single-term NDP government, claiming it had ruined the province’s finances and that any future government would be just as radical, despite Barrett’s new approach.

“Don’t be fooled,” Bennett warned. “They haven’t changed their spots; they have just put on a cloak to cover them up.”

“Before the election,” he added, “they act like Groucho Marx; it’s only after the election they act like Karl Marx.”

A key factor deciding Social Credit’s re-election would be the state of the Progressive Conservatives. Party leader Victor Stephens couldn’t gain any traction, instead garnering the most attention when he complained about the lack of support he was getting from Joe Clark’s federal Tories. There were claims the PCs had a secret deal with the Socreds, ensuring the federal party would provide no assistance to the provincial party in exchange for some funding for federal Tory candidates from Social Credit coffers.

One anecdote related to the PC campaign that was reported in the Globe and Mail was how “two Tory candidates decided to ‘come out’ as homosexuals at a Vancouver public meeting after an NDP candidate cracked that he’d ‘rather be gay than Tory’.” In a sign of how things have changed since the 1970s, the reporter used this anecdote as a reflection of how the Tories, rather than the NDP, lacked candidates who were “clear winners”.

As election day approached, the race looked tight. The NDP had run a smooth campaign and set the narrative on most days, but the increased chances of an NDP victory also ensured that reluctant Socred voters would cast a ballot, doing some of Bennett’s work for him. Social Credit also outspent the NDP by more than two-to-one, spending $2.4 million, worth roughly $9.5 million today.

Bill Bennett and the Socreds needed every advantage they could get (and, later on, their campaign would be tarred by charges of ‘dirty tricks’ involving phoney letters to the editor and unaccounted-for slush funds). The party lost four seats but secured a small majority government with 31. The party’s share of the vote dropped slightly to 48.2%, but it was enough.

The New Democrats took 26 seats, with gains in northern B.C., Victoria, Surrey, Coquitlam and Burnaby. With 46% of the vote, the NDP had jumped nearly seven points from 1975 as more than 94% of British Columbians backed one of the two big parties.

The PCs took just 5.1% of the vote and lost their only seat, while the Liberals dropped 0.5 points, with nearly all of their lost support going to the New Democrats.

It was the first time in British Columbia since the turn of the century and the beginning of partisan politics that no Independents or third-party MLAs won a seat. B.C.’s politics had polarized in a way that wouldn’t change until the final collapse of the country’s last Social Credit government in 1991.

1986 B.C. Social Credit leadership

A flamboyant premier for B.C.

July 30, 1986

When Bill Bennett announced he would resign the B.C. premiership and leadership of the governing Social Credit Party, it came as a complete surprise. Even his cabinet was taken unawares — they were meeting in Victoria when Bennett made his announcement at a news conference in Vancouver.

Bennett had governed the province for just over 10 years by 1986. The B.C. Socreds had only ever been led by a Bennett for more than three decades, going back to when Bennett’s father, W.A.C. Bennett, became Socred leader and B.C. premier in 1952. The younger Bennett felt that it was finally time for renewal within the party, and that he wouldn’t make the same mistake as his father did by staying on for too long.

The surprise announcement kicked off something the Socreds hadn’t experienced before in British Columbia: a seriously contentious leadership race (Bill Bennett easily succeeded his father in the previous contest in 1973).

The list of contenders grew and grew until 12 names were on the ballot.

There were four frontrunners, the most well-known being Bill Vander Zalm.

Few media descriptions of him failed to use the word “flamboyant”. A Dutch immigrant, Vander Zalm had made a fortune in the gardening industry and had a varied political career behind him. He had been mayor of Surrey, a B.C. Liberal leadership hopeful, Socred MLA, cabinet minister and a failed Vancouver mayoral candidate.

“Stories about Vander Zalm abound,” wrote Tim Harper in the Toronto Star. “The man whom Vancouver mayor Mike Harcourt once called the ‘minister of miseducation and human misery’ is best known for his war on welfare here when he implied that anyone who was not working was lazy. He greeted René Lévesque’s election by saying that he would be glad to see Quebec out of Canada. Later, he called Lévesque ‘a frog.’”

Vander Zalm appealed to the populist grassroots of the party, drawing support from across the province.

Also drawing support from the party’s old guard was Grace McCarthy, a long-time Socred stalwart first elected in the W.A.C. Bennett years. A former party president, a cabinet minister and an MLA with significant backing in the Lower Mainland, McCarthy had a lot of favours to call on after her years of working in the party trenches.

If Vander Zalm and McCarthy were the two populists, the two Smiths (unrelated) represented the establishment.

Brian Smith, the attorney general and a Victoria MLA since 1979, had a clean record as a cabinet minister — something that couldn’t be said for everyone around that table.

Bud Smith, principal secretary to Bill Bennett until he left his post to run for the Social Credit nomination in his native Kamloops, was pitched as the ‘renewal’ candidate. Just 40 and without experience as an elected official, others in the party quickly grew to resent his candidacy, particularly those in cabinet. He was dismissed as a Yuppie who needed help from easterners to run his campaign. Like Brian Smith, Bud Smith was receiving help from organizers from the Ontario Tories, and was generally supported by federal PCs.

There were eight other candidates in the running, though none were considered anything but longshots.

There was Jim Nielsen, a Richmond MLA and cabinet minister best known for showing up at the legislature with a black eye inflicted upon him by the husband of his mistress.

There was Stephen Rogers, who had resigned from cabinet after pleading guilty to failing to disclose all his investments. He was eventually cleared, but Bennett had continued to treat him as persona non grata.

There were low-profile Socreds like John Reynolds, Cliff Michael and Bill Ritchie, sitting PC MP Robert Wenman, Mel Couvelier, the mayor of Saanich, and a young Kim Campbell who warned delegates at the convention, in a dig at Vander Zalm, that “it is fashionable to speak of leaders in terms of their charisma. But charisma without substance is a dangerous thing.”

The contest was a classic fight between the grassroot populists and the professional establishment types. The Smiths got help from Ontario’s Big Blue Machine, while Vander Zalm toured delegate-selection meetings in an antique red fire truck. There were other divisions, too, such as between the ins and the outs of cabinet, or between the dyed-in-the-wool provincial Socreds and the federal Tories. In most of these divides, it was between Vander Zalm and McCarthy on one side and the two Smiths on the other.

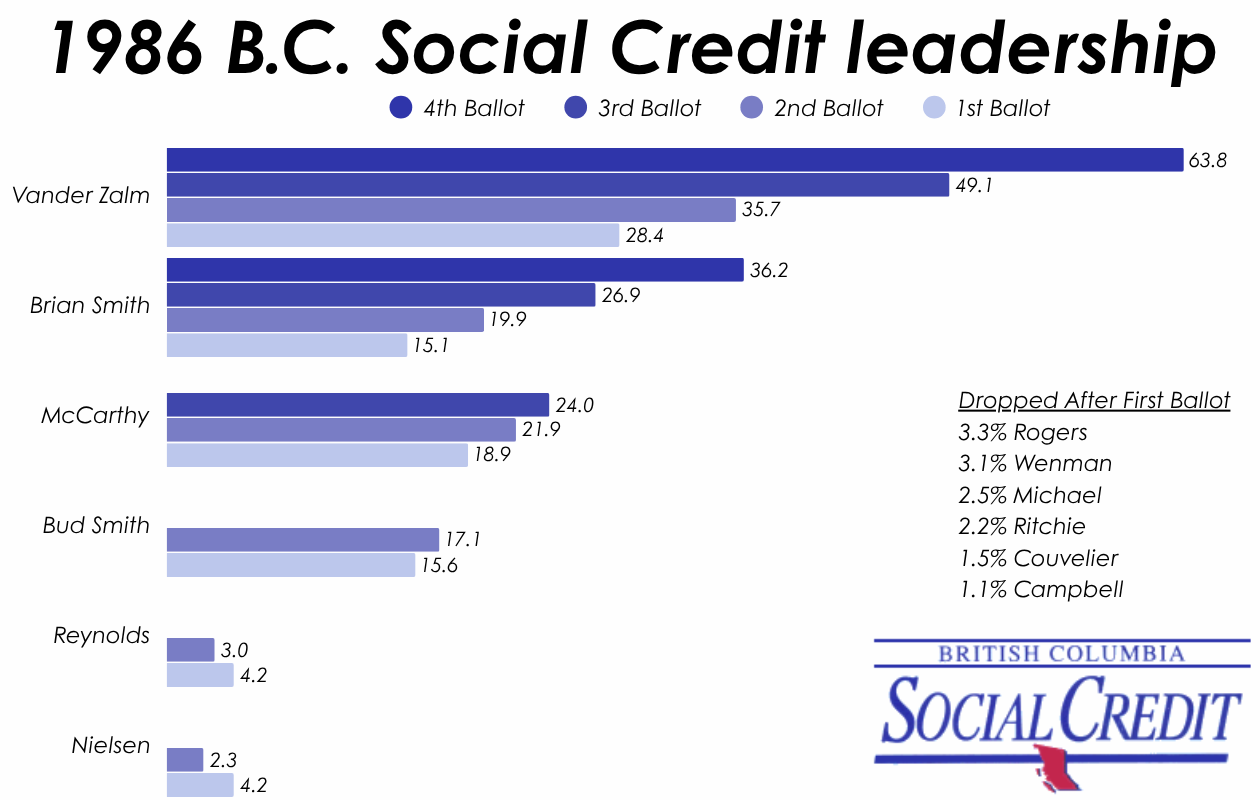

When the results of the first round of voting in Whistler were announced, it was clear that this was a race favouring the populists. Vander Zalm finished well ahead with 28% support, followed by McCarthy at 19%, Bud Smith at 16% and Brian Smith at 15%. No other candidate got more than 4%, with Kim Campbell finishing last. She was eliminated, but Rogers, Wenman, Michael, Ritchie and Couvelier dropped out, too.

Support for Reynolds and Nielsen dropped on the second ballot, as Vander Zalm got the lion’s share of support from those who had dropped off. But McCarthy wasn’t growing enough — there was lots of sympathy for her within the party, but she wasn’t seen as a potential premier. The anybody-but-Bud campaign was also having an impact, as Bud Smith picked up only 17 new votes to Brian Smith’s 59. Bud had fallen from third to fourth.

The most dramatic movement of the convention then occurred when Bud Smith threw his support to Bill Vander Zalm. It was expected that the two Smiths would coalesce, but instead Bud Smith went to Vander Zalm, saying he was the best hope for renewal within the party.

The move solidified Vander Zalm’s lead as he grew from 36% to 49% of delegates’ votes. McCarthy had entirely run out of steam, and fell to third place behind Brian Smith, who jumped from 20% to 27%, ahead of McCarthy’s 24%.

As expected, most of McCarthy’s delegates went to Vander Zalm on the final ballot. The fellow populist increased his vote by 176 to Smith’s 112, and Vander Zalm won after 10 hours of voting with 64% support.

The win represented a swing of B.C. Social Credit back to the old days of W.A.C. Bennett and the Socreds’ somewhat undefinable brand of free enterprise conservative populism. A win by either of the Smiths would have continued the process of the party becoming a more professional, conventionally-conservative organization that Bill Bennett had begun.

Perhaps accordingly, Vander Zalm was not Bennett’s choice — though he made nice at the convention. But at the transitional meeting that was supposed to take place between Bennett and Vander Zalm shortly afterwards, Vander Zalm didn’t show up, sending instead a member of his campaign team.

It was the start of a tumultuous time for the Socreds in British Columbia. Vander Zalm would win an election he called later in 1986, but his time as premier would be relatively short. Beset by various scandals and controversies, Vander Zalm would resign before the end of his first full term. His successor, Rita Johnston, had the honour of being Canada’s first female provincial premier — an honour not given to Grace McCarthy in 1986. Johnston would lead the Socreds to defeat in 1991, and the party would virtually cease to exist not long after that.

2005 British Columbia election

Back to normal in B.C. politics

May 17, 2005

The two-party system that had developed in British Columbia in the 1970s and 1980s between Social Credit and the New Democrats collapsed in 1991, when the Liberals replaced the Socreds as the main alternative to the right of the NDP. Groping about for a new system in 1996, the NDP and Liberals had to fight off two new upstarts in the Reform Party and the Progressive Democratic Alliance.

Then, in 2001, B.C. nearly ended up with a one-party system.

In that cataclysmic election for the governing New Democrats, the party then under Ujjal Dosanjh was reduced to just two seats. The B.C. Liberals under Gordon Campbell came to power for the first time in more than half a century, winning 77 of 79 seats on offer.

What seemed like the makings of a new political dynasty faltered out of the gates. The Liberals cut personal income tax immediately after coming to power, but the reduction in government revenues led to swingeing service cuts and hated user fees. Campbell’s own image took a beating when he was arrested for drunk driving in Hawaii a few years into his mandate.

Things were going badly for the Liberals, who were at times even trailing the NDP in the polls. But the economy was improving and British Columbians were feeling more upbeat. By the time the 2005 election approached — the first in Canada to be held according to fixed-date legislation — the Liberals had re-established a seven-to-nine point lead over the New Democrats, now under the leadership of former school board chair Carole James.

The Liberals would run on their record of economic growth (“B.C. is Back” was the slogan) and their notion of a coming ‘Golden Decade’ for the province, their platform effectively being the budget that had been presented earlier in the year. Hoping to mollify those who saw Campbell as a heartless neo-conservative, the Liberals intended to run more toward the centre, promising to spend on healthcare and education.

The New Democrats, adopting the slogan of “Everyone Matters”, went on the offensive against the Liberals’ record of cuts. But the NDP, too, was moderating itself. James promised to balance the budget and implement no new taxes.

As an incumbent government with a lead in the polls, the Liberals ran a low-key campaign with few daily events, in contrast to the frenetic pace of the James campaign. They tried to tie the NDP to labour organizations, stoking fears that an NDP victory would be swiftly followed by a teachers’ strike, as James had pledge to give teachers that right back.

The front runners campaign wasn’t going as well as the Liberals would have liked, however. In a debate in which Campbell, James and Green leader Adriane Carr participated, James was seen to have been a strong performer.

By the end of the campaign, the NDP had closed the gap somewhat. At the outset, talk had been that the NDP could win 20 or 25 seats, maybe not enough to secure James’ leadership of the party. With days to go, talk had moved to the NDP winning 30 or more seats — maybe even government.

Also on the ballot was a referendum on electoral reform, asking British Columbians whether they wanted to switch from first-past-the-post to a single-transferable vote. While a majority (58%) ended up voting for it, that had fallen just short of the 60% threshold that had been set for implementing the change.

The result showed the re-emergence of B.C.’s two-party system, with the Liberals and NDP finishing within just a few points of each other. After such a landslide in 2001, the Liberals were inevitably going to lose a lot of seats — and they did. The party captured 46, down 31 from the 2001 election, and saw their share of the vote drop by 11.8 points to 45.8%.

But Campbell had been re-elected, the first B.C. premier to win two consecutive elections in 22 years. A lot of his colleagues around the cabinet table, however, went down to defeat.

The NDP went from just two seats to 33, gaining 19.9 percentage points to finish with 41.5%. The New Democrats made significant gains on Vancouver Island and in and around the city of Vancouver, and also made some pick-ups in the Interior. But places like Richmond, Burnaby, the Fraser Valley, the Okanagan and the North stuck with Campbell’s Liberals.

The Greens saw their vote drop three points as they finished with 9.2%. The party finished second in only a single riding, but showed some strength along the Georgia Strait where Carr was running (and was defeated).

Still, the two-party system had been re-established — and it would be tough to get unstuck. Each party’s vote and seat numbers would hardly change in 2009 and 2013. Only in 2017, when a few more seats flipped and the Greens held the balance of power, would things change again in B.C. politics.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections B.C. and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

British Columbia’s Premiers in Profile: The Good, The Bad and The Transient by William Rayner

Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia by Patricia E. Roy

Duff Pattullo of British Columbia by Robin Fisher

W.A.C. Bennett and the Rise of British Columbia by David J. Mitchell

The Art of the Impossible: Dave Barrett and the NDP in Power, 1972-1975 by Geoff Meggs and Rod Mickleburgh

Bill Bennett: A Mandarin’s View by Bob Plecas