#EveryElectionProject: Alberta

Capsules on Alberta's elections from The Weekly Writ

Every installment of The Weekly Writ includes a short history of one of Canada’s elections. Here are the ones I have written about elections and leadership races in Alberta.

This and other #EveryElectionProject hubs will be updated as more historical capsules are written.

1905 Alberta election

Alberta’s first election

November 9, 1905

When Wilfrid Laurier, the Liberal prime minister, announced that two provinces would be carved out of the North-West Territories in 1905, it was understood that they would governed by Liberal premiers. After all, it was a Liberal MLA who was appointed to be Alberta’s first lieutenant-governor, and he accordingly named the new Alberta Liberal leader to be the new province’s first premier.

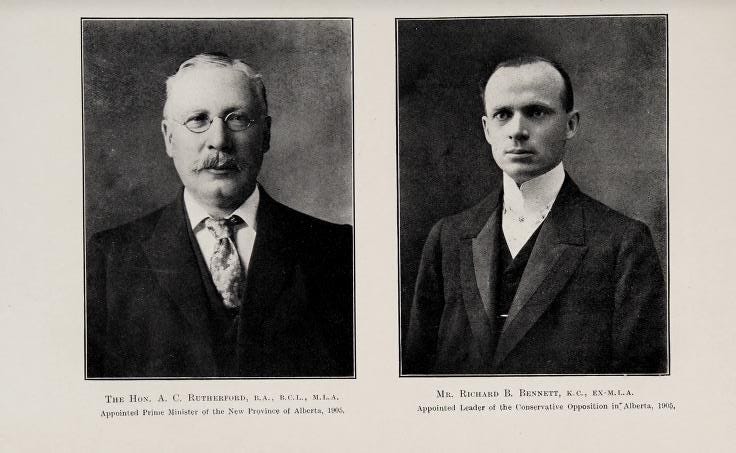

That man had been chosen in August 1905 at a convention in Calgary attended by about 150 delegates. These Liberals had to get a provincial organization up and running, and to lead it they chose Alexander Rutherford, an unflashy lawyer who had served in the territorial assembly since 1902. Aiding his rise to the party leadership — and thus the premiership — might have been the fact that Rutherford had ruffled few feathers in his brief time in politics.

He wasn’t too keen on the terms of Alberta’s entry into Confederation that had been decided upon by Laurier, who imposed separate schools on Alberta to protect the French Canadian Catholic minority and retained federal government control over Alberta’s public lands and natural resources. But, Rutherford was a Liberal and a team player.

After naming a cabinet, Rutherford set November 9, 1905 as the date of Alberta’s first election. His Liberals would be opposed by the Conservatives, who named a Calgary lawyer named Richard Bedford Bennett as their leader. Their convention was held in Red Deer, the first in a long list of Alberta political events held in the city.

Bennett and the Conservatives went on the attack against the Liberals and the Alberta Act which, they claimed, infringed on provincial autonomy. But Rutherford and the Liberals had a powerful ace up their sleeves: patronage. Even if they had only been in office for a few weeks, that time gave them the chance to reward their friends.

Alberta also happened to be, contrary to its modern political make-up, a pretty Liberal place. The influx of immigrants into the province from around the world gave the party that brought them to the country a natural constituency.

The 1905 Canadian Annual Review highlighted the mosaic that Alberta had become:

Victoria was largely Galician [Eastern European] in its vote. Vermilion had a population mainly American in character … Leduc was strongly French-Canadian in complexion and the local Conservative candidate, Mr. C. A. Simmons, was, by the way, a relation of Sir Charles Tupper. In Wetaskiwin there was a considerable Swiss vote … Stoney Plain was almost entirely German in its racial complexion. Cardston was largely a Mormon constituency.

Farmers were also pre-disposed to supporting the free-trade Liberals over the protectionist Conservatives. In the 1904 federal election, Laurier had carried three of the five seats that occupied what would become Alberta and was only a few hundred votes away from winning all five.

Ably run by Liberal MP Peter Talbot, who had been Laurier’s preferred choice for the premiership before he declined, the Liberal campaign focused voters’ attention on Bennett. Unlike the inoffensive Rutherford, Bennett had made enemies as a lawyer representing some of the most powerful (and hated) companies in Alberta — including the Canadian Pacific Railway.

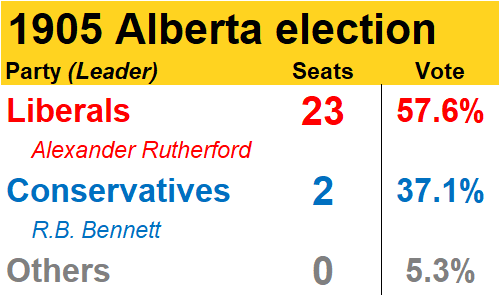

To little surprise, Rutherford’s Liberals prevailed easily, winning 23 of 25 seats and about 58% of the vote. The Conservatives were only able to win two ridings: Rosebud, north of Calgary, and High River, south of it.

Bennett, running in Calgary, went down to defeat.

Though his time in office would be relatively short (he resigned in 1910), Rutherford would be the first Liberal premier of what would be Alberta’s first political dynasty. The party would remain in office for 16 years, until it was replaced by the United Farmers of Alberta in 1921.

More than 20 years after his defeat in Calgary, R.B. Bennett would go on to take over the leadership of the national Conservative Party. After winning the 1930 election and becoming prime minister, Bennett would be “rewarded” with leading the country through the Great Depression and being defeated after a single term in office.

1909 Alberta election

The last Liberal landslide in Alberta

March 22, 1909

In office since the province’s creation and the subsequent 1905 election, Alexander Rutherford and the Liberals had spent their first years in power setting up the institutions and infrastructure of newborn Alberta.

Lewis G. Thomas, writing in The Liberal Party in Alberta, said that heading into the 1909 election the Rutherford Liberals “could point to a record of achievement, to the foundations soundly laid for a new province. The province had acquired a publicly owned telephone system and extensive public works had been carried out. The interests of agriculture had been promoted and those of labour given consideration. A judicial system was in good working order, the educational system was functioning adequately although salaries were low and a scarcity of male teachers was feared.”

But a growing, bustling province meant there was a need for more railways. Just a few months before the election was called, Rutherford announced a new policy on the part of the Alberta government: it would guarantee the bonds for three railway projects and so gain these much-needed railways without a significant investment of public money.

It was the kind of safe, sound policy that Rutherford had come to be known for and the Liberals launched their campaign under the slogan “Rutherford, Reliability and Railways”.

It helped that the Conservatives weren’t really capable of putting up much of a fight. The party was effectively leaderless. After R.B. Bennett was defeated in 1905, Albert Robertson took over as leader of the official opposition in the legislature. But he wasn’t particularly beloved by Conservatives (musing about breaking the link with the British Empire, maybe even by annexation to the United States, didn’t help) and he was never permanently given the role. Even when the man they did have in mind declined at the party’s convention, the Conservatives weren’t willing to name Robertson as party leader. R.G. Brett, who was named president of the party, was nominally given the title.

Bennett, though, was still the leading attack dog and he led that attack from Calgary, charging that the Rutherford government had given favour to Edmonton over his city, what with the capital going to Edmonton and the University of Alberta going to Rutherford’s home town.

The Conservatives had some progressive policies in their platform, including the public ownership and operation of the railways, more direct democracy through recalls and referendums and pledges for significant government spending in building up Alberta’s infrastructure.

But the Liberals had all the advantages of an incumbent government and were ready for the campaign. They went on the attack themselves, charging that the Conservatives were in the pocket of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The CPR was dead-set against the Liberals, in part because their government wanted to fund new railways that would compete with it.

The disarray on the Conservative side helped mitigate the fact that Rutherford, while respected, wasn’t an electrifying campaigner or great speaker. He was also more non-partisan than a lot of Liberals would have liked. Before election day, Rutherford appealed to Albertans in the Strathcona Plaindealer for “the elimination of selfish and partisan considerations. I appeal to you not as Liberals or Conservatives, but as Albertans. The Province must stand before the party.”

The Liberals had no trouble winning another huge mandate from Alberta’s (male) voters. The party captured 36 seats, with one Independent Liberal also being elected. The legislature increased in size significantly and the Liberals won nearly all the extra seats, including eight by acclamation. The party’s share of the vote was up slightly to just over 59% — or comfortably over 60% including the Independent Liberal candidates.

Only two Conservatives pulled off a victory. One of them was R.B. Bennett in Calgary, but neither Brett nor Robertson were elected to join him in the legislature. Bennett would take over as opposition leader before heading to Ottawa.

Among the small, motley crew of opposition MLAs were Charlie O’Brien, a socialist elected in the Rocky Mountain riding where the province’s coal mines were located, and future Conservative leader Edward Michener, who won this time as an Independent.

Rutherford’s big majority victory turned out to be no guarantee of security. Allegations of corruption (which remain unproven) and charges of incompetence (which appear closer to the mark) coming from a contract awarded to the Alberta & Great Waterways Railway undermined Rutherford’s authority. Exacerbated by divisions within the Liberal caucus, this forced Rutherford to resign as premier in 1910.

The Liberals would have trouble shaking off the A&GW scandal, though they would manage to win two more times before falling to the United Farmers of Alberta in 1921. But the Liberal dominance of Alberta was over — single-digit opposition caucuses in Alberta would be a thing of the past. At least, for a little while.

1930 Alberta Liberal leadership

North vs. South in the Alberta Liberal Party

March 27, 1930

From its creation in 1905, Alberta was Liberal. The Alberta Liberal Party formed the first dynasty in a province that likes its dynasties, winning each of the province’s first four elections. But the Alberta Liberals’ last time in office came to an end in 1921, and the party hasn’t been in power since.

That election saw the rise of the United Farmers of Alberta, an agrarian populist party that, along with the Progressives at the national level, broke the old party system. The Farmers beat Charles Stewart’s Liberals in 1921 and did the same in 1926, when the Liberals were under the leadership of Joseph Tweed Shaw. By the time the next election approached in 1930, the Liberals needed a new leader to replace him.

Leadership contests were new-fangled things at the time, having only become established practice in Canadian politics little more than a decade earlier. They weren’t long drawn-out campaigns with well-known candidacies, leadership debates or membership drives. It often all came down to what happened on the convention floor.

For the Alberta Liberals, who would hold their leadership convention on March 27, 1930 in Calgary, it wasn’t even certain who would stand for the job a few days out. A few candidates were rumoured to be interested, but it wasn’t even known whether or not Shaw would allow his name to be put forward again until, the week of the convention, he finally declared he would decline any nomination.

By the time the convention was held (on a Thursday), it was obvious that the race would primarily come down to two candidates — one representing the southern wing of the party, the other representing the north.

The southern standard-bearer was John Walter McDonald, a lawyer and mayor of the small town of Fort MacLeod. Born in Toronto but living in Alberta for more than 20 years, McDonald had run as the Liberal candidate in the Macleod riding, losing to the UFA in 1926.

Newspapers differed on his chances, the Edmonton Bulletin claiming the southerner was largely unknown in the north while the Lethbridge Herald suggested the local boy, who it called “an able public speaker, a life-long Liberal and a close student of public affairs”, was well known to Liberals throughout the province.

Alberta Liberals from northern Alberta coalesced around William Robinson Howson, an Edmonton lawyer without political experience but propped up by the support of younger delegates to the convention.

In addition to these, two others were nominated from the convention floor.

There was John Campbell Bowen, a former Edmonton MLA who briefly served as party leader until Tweed took over in 1926, and Hugh John Montgomery of Wetaskiwin, another former MLA who was defeated in the Farmers’ 1921 victory.

Hector Lang, the MLA for Medicine Hat, and George Webster, an MLA for Calgary, were also nominated by delegates. But they declined their nominations, Webster opting to nominate McDonald himself.

“One of the hottest fights in the history of the Liberal party in this province,” according to the Lethbridge Herald, had to go to three ballots. On the first ballot, McDonald emerged with the most support at 40%, followed closely by Howson at 36%. Bowen trailed in third with 16.5%, while Montgomery came up in fourth with 8%.

With more than 60% of the vote between them, it seemed possible that the candidates from the north could team up to beat McDonald, the lone southern candidate.

That didn’t happen. On the second ballot, Bowen and Montgomery lost about nine percentage points, nearly all of that going to McDonald. On the final ballot, McDonald emerged victorious with 54% of delegates’ votes, Howson growing only to 40%, Bowen dropping to 6%.

Perhaps delegates had decided they wanted a candidate with a little more political experience than the neophyte Howson. The result, though, was interpreted by some as the southern wing of the Liberal Party flexing its organizational muscle.

McDonald wouldn’t have long to get comfortable in the job. Premier John Brownlee of the United Farmers set the date for the 1930 election for June 19, less than three months after the seatless McDonald took over the Liberal Party leadership. While McDonald would lead the Liberals to a few modest seat gains, one of those was not his own. Again without a seat, McDonald’s leadership of the party wouldn’t last and, in 1932, he was replaced by Howson. No longer a neophyte, Howson had managed to do what McDonald couldn’t in 1930: win a seat in the legislature.

1944 Alberta election

The importance of being Ernest

August 8, 1944

From the moment that William Aberhart and Social Credit stormed to power in Alberta in 1935, the province’s politics were a punchline for the rest of the country. Pledging to implement Social Credit’s unorthodox, unworkable theories of monetary reform, Aberhart failed to deliver the promised $25 monthly dividend to Albertans and had his legislation blocked and disallowed by the federal government and the lieutenant-governor.

The province’s experiment in Social Credit almost ended in 1940, when opponents to Aberhart formed a united front and the Socreds only narrowly secured another term in office. It would be Aberhart’s last, however, as he died in 1943.

The heir apparent to “Bible Bill” was Ernest C. Manning, only 34 when the Social Credit caucus unanimously chose him as leader and premier. Manning had been Aberhart’s disciple and right-hand man, and accordingly took over Aberhart’s Back to the Bible radio show along with the reins of the province.

Manning was a believer in Social Credit, but he was also pragmatic. Despite all of the turmoil surrounding the Aberhart years, Alberta was coming out of the Depression with a booming economy and better services. Manning made a few half-hearted attempts to show the Socreds that he was still intent on trying to implement Aberhart’s programme, but he also pledged to keep his government’s efforts within provincial jurisdiction. The passing of Aberhart made it possible for Social Credit to become a more serious party — and for the failures of the past to be forgotten. Ernest Manning was no William Aberhart, but in a good way.

In any case, by 1944 Manning had something more potent to take to voters than the wacky theories of Social Credit: anti-socialism.

The Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation was becoming a strong force in Canadian politics. It was competing with the Liberals and the Progressive Conservatives at the national level. It finished second in the 1943 Ontario election and shocked the country when it formed a government for the first time after the 1944 Saskatchewan election. Just as Aberhart had set his sights on Saskatchewan after taking power in Alberta, Douglas and the CCF was setting its sights on Alberta.

Elmer Roper, who won the CCF’s first seat in Alberta in a 1942 byelection, was leading a party with a strong organization. He pledged to nationalize Alberta’s industries, including the exploitation of its natural resources. He provided a good target for Manning, who emphasized Social Credit as a “free enterprise party”.

Roper criticized Manning for "going conservative”, as Social Credit was seen in some quarters as a left-wing movement in the 1930s. And, in some ways, it was — Social Credit had brought in some “socialist” legislation, instituting publicly-funded care for tuberculosis patients and free surgeries, hospitalizations and examinations for cancer patients.

But Manning’s vision of the role of government was different than the CCF’s. Whereas the CCF wanted to nationalize industry and put into place universal programs, Manning believed that the state should only step in where people couldn’t take care of themselves. For those who could, individual responsibility was what mattered — for Manning, Social Credit was for private individualism, CCF was for state socialism.

Though the fight was primarily seen as one between Social Credit and the CCF, another major player was the Independent Citizen’s Association, a coalition of former Conservatives, Liberals and United Farmers who were united in their opposition to the Socreds. They had nearly defeated Aberhart in 1940, but by 1944, and under the leadership of James Walker, the party’s cohesion was falling apart. Also on the ballot were the Labour Progressives under James MacPherson, the successors to the Communists who had been banned only a few years before.

A correspondent for The Globe and Mail in Edmonton wrote at the campaign’s outset that “right now, it’s almost too early to guess who’ll win from among the three major groups — Social Credit, C.C.F. and the Independents. But it will be an up-and-at-’em battle all the way.”

That battle became literal at one CCF meeting in Lethbridge, where the Social Credit candidate in attendance was “ejected and punched”. National CCF leader M.J. Coldwell, who was campaigning in Alberta, tried to downplay the affair, but Social Credit was happy to use the incident as an example of the “Gestapo methods” that the CCF would use if they came to power.

Nationally, the Alberta election was overshadowed by the campaign taking place in Quebec on the very same day. There, the Liberals under Adélard Godbout were in tough against Maurice Duplessis’s Union Nationale, and the electoral campaign served as a proxy for Quebec’s opposition to conscription. By contrast, Ernest Manning had pledged to support the federal government’s war effort and members of the armed forces were able to select three extra MLAs to represent the Army, the Navy and the Air Force.

Though the outcome of the election was seen as unpredictable, things were moving in Social Credit’s favour. Fears of the rise in popularity for the CCF was sapping the support for the Independents, pushing them toward Social Credit. The Calgary Herald and Edmonton Journal, the two major Alberta newspapers long dismissive of and opposed to Aberhart’s government, reluctantly endorsed Manning, urging voters to rank Social Credit candidates second after the Independents on the ranked ballots that were then in use, an admission that, for all its faults, they preferred a re-elected Social Credit government to a CCF victory.

In the end, it wasn’t close at all. So sweeping was Ernest Manning’s victory that the Canadian Press called the election just 26 minutes after the polls had closed.

Social Credit took 51.9% of the vote, a gain of nine points over the near-death experience of the 1940 election. The party won 51 seats, 15 more than in the last election, sweeping every riding outside of the multi-member Calgary and Edmonton districts.

Roper and the CCF finished second in the votes with 24.9%, a 14-point jump over 1940. But they were only able to elect two MLAs, one in Edmonton (Roper) and one in Calgary. Instead, the Independents managed to finish second in the seat count, winning three seats (two in Calgary and one in Edmonton). Their support had plunged 26 points, however, to just 16.8%.

Also elected was William Williams under the banner of the Veterans & Active Force Party, while the Labour Progressives were shut out, capturing 4.3% of ballots cast.

Manning’s victory in 1944 would establish Aberhart’s shaky Social Credit Party as the dominant force in Alberta politics for nearly three decades. Manning would combine significant spending, social conservatism and anti-socialism, along with the economic prosperity that came with the discovery of oil at Leduc in 1947, to win seven straight elections. But the dynasty would end with Manning — the party was defeated in the first election after his retirement and shortly thereafter drifted into irrelevance.

1958 Alberta Progressive Conservative leadership

Alberta PCs hope to ride the Diefenbaker wave

August 16, 1958

Being a Conservative in Alberta was once as tough as being a Liberal.

After Social Credit’s surprise win in the 1935 election, the Alberta Conservatives teamed up with the Liberals (and defeated United Farmers) to form a united front against the Socreds as part of the Independent Citizen’s Association.

They weren’t successful at dislodging Social Credit from power after repeated attempts and it wasn’t until 1952 that the Alberta Conservatives ran a few candidates of their own once again.

The party had yet to get much of a sniff at power in the province and weren’t getting much closer. Under John Page, the Conservatives managed to win three seats and 9% of the vote in 1955 — and even that poor showing was still their best performance in a quarter century.

But things were looking up for the Progressive Conservatives across the country by the end of the 1950s and the Alberta Tories finally opted to bring their party’s name in line with their federal cousins.

It certainly seemed like a good idea after John Diefenbaker’s landslide victory in 1958. In that election, the federal PCs went from just three seats in Alberta to a clean sweep of all 17, taking 60% of the vote and reducing the previously-dominant federal Social Credit to just 22%. Ernest Manning, the Socred premier, quipped that voters had “put all their eggs in one basket and shot the hen”.

Flush with the victory of their federal counterparts, the Alberta PCs were finally ready to name their first permanent leader since 1937 and scheduled their convention in Edmonton on the 15th and 16th of August, 1958.

Taking place in the newly-completed Jubilee Auditorium in Edmonton, the convention was attended by some 1,000 delegates and guests, including about 400 who would cast a ballot. Duff Roblin, who had brought the PCs to power just a few months earlier in Manitoba, delivered the keynote address.

The speakers took aim at the Manning government, which had tried to pre-empt the PC convention by announcing it’s “gigantic” five-year plan, including a series of new investments and the end of the oil dividend that had been paid out to Albertans. The PCs charged that the Socreds had based their plan on polls to “see what would bring them the greatest number of votes”.

The front-runner for the PC leadership was W.J.C. Kirby, a 48-year-old MLA for Red Deer and president of the party since 1953. Cam Kirby had the edge over his rivals due to his legislative experience and his familiarity within the party.

His main rival was Alan Lazerte, a 30-year-old lawyer from Edmonton with support from the northern delegates. He told the convention that they were “choosing the next premier" and criticized the Socreds for making the legislature “more like a puppet show than a place of parliamentary debate”.

Also in the running was Calgary MLA Ernest Watkins, who described Manning’s five-year-plan as having “a pinch of Conservative policy, a tablespoon of sugar and lots and lots of water”, as well as Ernest Toshach, the mayor of Drumheller, and Gifford Main of Edmonton.

Kirby was widely seen as the favourite, but he was also seen as a centralizing figure. Those who wanted a more grassroots approach to party organization gathered around Lazerte.

When the first ballots were counted, Kirby was indeed in front with 38% of delegates’ votes, followed by Lazerte at 27%. Watkins, Toshach and Main followed. A second ballot clarified matters when support for the bottom three candidates dropped and support coalesced behind Kirby and Lazerte.

Though Lazerte gained on Kirby in that second ballot, Kirby widened his lead on the third with the elimination of Main and a reduction in support for Toshach and Watkins. On the fourth ballot, Watkins fell further and Kirby was able to win without the need for a fifth round, taking 52% of the vote to Lazerte’s 40% and Watkins’s 8%.

On winning the title, Kirby promised “better government” for Albertans and that he would transform the PCs into the chief alternative to the Socreds.

In the provincial election that followed less than a year later in June 1959, Kirby only half-delivered on his pledge. The Progressive Conservatives did indeed emerge as the main rival to the Socreds and finished second in the vote count with 24%, a significant jump from their showing in 1955. But Social Credit also saw its support increase to 56%, leaving no opposition party with more than one seat — including the PCs, who elected only a single candidate: Ernest Watkins.

Kirby would resign early in 1960 and the PCs would spend a little more time in the wilderness. The PCs weren’t selecting the next premier in 1958, but they would make that choice only a few short years later with the elevation of Peter Lougheed to party leader in 1965.

1962 Alberta Liberal leadership

Small-town mayor becomes Alberta Liberal leader

January 14, 1962

It’s been a long, long time since being an Alberta Liberal was easy.

The struggles of the Alberta Liberal Party are not just a recent phenomenon — and the blame can’t all be laid at the feet of one Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Take the 1959 Alberta election, for instance. In that vote, Ernest Manning’s Social Credit captured 61 of 65 seats on offer. The Liberals, then under Grant MacEwen, managed just 14% and a single seat. It wasn’t MacEwen’s.

So, the job of being the leader of the Alberta Liberal Party became vacant. And it stayed that way for more than two years.

By 1962, the Liberals decided it was time to fill that vacancy. The names of a few promising candidates were bandied about, but in the end it came down to just two.

One was Bryce Stringam, a former MLA who was elected as an Independent in 1955 and served for one term in the legislature.

The other was Dave Hunter. The mayor of the small northern community of Athabasca, Hunter was serving as president of the Union of Alberta Municipalities and was the odds-on favourite to win.

About 500 delegates gathered in Calgary in January 1962 for the convention, an event that was enlivened by a fiery performance by Ross Thatcher, leader of the Saskatchewan Liberals. Though himself only an opposition leader in Regina, he had reinvigorated the Liberal Party there and would eventually end the CCF’s long run of power in 1964.

For now, though, Thatcher’s job was to rally the Liberal troops in this neighbouring province. And it wasn’t his first time — in the previous fall, he had spoken at a rally in Edmonton where he “apparently inspired some members of the Alberta [Liberal] executive to the point where they were all set to go out and fight. Unfortunately,” wrote Andrew Snaddon, the Globe and Mail’s correspondent in Calgary, “they don’t seem to know what they are fighting about.”

The Liberals recognized that they were unlikely to defeat Social Credit. The party had governed Alberta for more than a quarter century and Manning looked (and, as it turned out, was) unbeatable. But the Liberals had more hope at the federal level, believing that John Diefenbaker’s unpopular Progressive Conservative government was vulnerable. The PCs had swept all of Alberta’s seats in Diefenbaker’s 1958 landslide, but both the Liberals and Socreds believed they could win a few federal seats back in the upcoming vote.

That test was in the future, though. In January 1962, the Liberals had to choose their local standard-bearer to give the brand some new energy. And they chose Hunter by a substantial (unreported) margin.

Snaddon thought Hunter had potential.

“Athabasca is in the northern part of the province,” he wrote, “good Liberal ground in days past. He also has an advantage in rural-dominated Alberta in that he does not come from Calgary or Edmonton, for city interests are conflicting with rural ones.”

However, the Liberals faced an uphill climb.

“Mr. Hunter is not a spectacular orator, nor is he likely to be an inspirational leader,” Snaddon opined. “But he is said to be a determined man and a hard worker.”

The Liberals failed in their first test in the 1962 federal election. While Diefenbaker’s PCs were reduced to a minority, they only lost two seats in Alberta — both to Social Credit.

In the next provincial election in 1963, Hunter would have only limited success. The Socreds won 60 of 63 seats and 55% of the vote, leaving the Liberals with just 20% support and two seats — neither of them Hunter’s.

His leadership would come to an end in 1964 when Hunter failed to win a seat in a byelection.

But Hunter’s short-lived leadership did get the Liberals back their official opposition status, even if it was with just two seats. It wouldn’t last for very long, however, and it would be another 30 years before the Liberals would be awarded that role again.

1966 Alberta Liberal leadership

Alberta Liberals choose a leader — for a little while

January 15, 1966

Politics was changing in the 1960s. Quebec was in the midst of the Quiet Revolution and the United States was reeling from first the election, and then the assassination, of John F. Kennedy. Student-led protests and calls for change emanating from south of the border were being heard in Canada, too, and before the decade was over the country would have its own youthful-seeming, mould-breaking prime minister.

But one place where politics was still very old-fashioned, at least for the time being, was Alberta.

The province had been governed by the Depression-era Social Credit Party since 1935. Since 1943, the premier had been the unflashy, deeply Christian and solidly conservative Ernest Manning. It didn’t seem like that was going to change anytime soon.

The Socreds dominated Alberta politics, leaving little room for any real opposition. The tiny opposition that was elected in the 1963 election was led by Dave Hunter and the Liberals. They won all of two seats, taking 20% of the vote. The Socreds, by comparison, won 55% of ballots cast and 60 seats.

The extent of Manning’s dominance was so great that, in 1965, Hunter felt he had better prospects as a federal Liberal — even in Alberta. He resigned his provincial leadership and ran for Lester Pearson’s Liberals in the 1965 federal election, placing a distant second in his riding of Arthabaska.

But with the Alberta Liberals now searching for a leader, there was a bit of optimism around the party’s chances. Social Credit was increasingly showing its age, and when the Liberals mounted their leadership convention the Ottawa Citizen’s correspondent, James H. Gray, noted that “greying heads were notably absent from the convention platform and the convention floor”. This was a more youthful, forward-looking party than it had been before. It was certainly more youthful than the Socreds.

Alberta was changing. Another party had an opportunity to be the vehicle of that change, according to Gray.

“The Alberta population has changed drastically in the past 15 years,” he wrote. “The Socred proportion has been drastically reduced by the huge influx of outsiders and by the attrition of time. A good half the population knows nothing and cares less about the economic conditions that spawned Social Credit.”

There were two front runners for the Alberta Liberal leadership, which would be decided on January 15, 1966.

There was Calgary alderman Adrian Berry, who had ran for the federal Liberals in the last election, finishing a respectable (but still distant) second in Calgary North.

His main rival was Robert Russell of Edmonton, the former executive secretary of the provincial party. According to the Calgary Herald, he hadn’t “cut his chances any by having corsages handed out to the female delegates” of the Women’s Liberal Association, who gathered to hear from the contestants in the days ahead of the vote.

Also on the ballot was Richard Broughton of Ponoka and Wilbur Freeland of Peace River.

A farmer and a veteran of the Second World War, in a couple years Freeland would become the grandfather of Chrystia, the future federal finance minister. For now, though, he was an also-ran in this contest, an “outspoken advocate of left-wing policies, such as public ownership of power”, according to the Herald. Broughton also had little shot and it probably didn’t help that he spent the final days of the campaign on vacation in Mexico.

The convention in Calgary was well-attended, with some 1,000 voting delegates and observers present. The Alberta Liberals wanted to spice up the contest a little and adopted a voting system reminiscent of the American primaries — delegates would choose leaders from within their groups, and have those leaders announce which candidate their group would be backing.

Drawing a queen of spades from a deck of playing cards, Berry spoke first to the convention. He sharply criticized the Social Credit government but he didn’t spare the Liberal Party either, saying “I’m not impressed with our organization in this province.”

The voting system, meant to create excitement, instead sparked confusion, delays and recounts, taking some energy out of the event. The presence of the youth delegates was felt, however, when they voted to add lowering the drinking age to 18 and legalizing birth control to the party platform.

The first ballot ended in a tie, with both Berry and Russell taking 231 votes, each heavily backed by their respective Calgary and Edmonton bases. Freeland took just 78 votes, while Broughton had only 15.

On the second ballot, Freeland’s support was cut nearly in half as most of his and Broughton’s backers went over to Berry. On the final ballot, Russell wasn’t able to pick up more than two votes to Berry’s 16, and that settled matters. Adrian Berry would be the new leader of the Liberals and the standard bearer for change in the province.

It wouldn’t last. Citing divisions with the party executive that made his position “untenable”, Berry resigned in November 1966. Michael Maccagno, who led the opposition in the legislature and who had been interim leader after Hunter’s resignation, resumed that role and kept it, leading an unprepared and divided party into the 1967 election held in May.

The unsteady Liberals weren’t able to become the vehicle of the new Alberta. Instead, it was Peter Lougheed and the Progressive Conservatives who displaced them, finishing second in the 1967 election with more seats than they had ever won since the formation of Social Credit. In 1971, the PCs would finally break the Socreds’ strangle-hold on the province — and the Liberals, now finally under Robert Russell, fell to just 1% of the vote.

1967 Alberta election

The beginning of the end

May 23, 1967

As Canada prepared to celebrate its centennial year, Albertans were on track to return to office the same party that had governed them since the Great Depression.

Four years after Ernest C. Manning led his Social Credit Party to its eighth consecutive victory, sixth under his leadership, the Socred dynasty that started in 1935 looked completely secure. The party had won 60 of 63 seats in the last election. Undoubtedly they’d dominate again.

And why not? Alberta’s economy was humming along and the people were enjoying the prosperity that came from the province’s oil industry. Sure, the Socreds had lost two of three byelections in the last session, but there was little need to worry about that.

After 24 years in office, Manning was instead thinking about retirement. He’d give Social Credit one more election before stepping aside. With that in mind, he presented a “White Paper on Human Resources Development” full of conservative social policies that could give his successor some direction.

The truth of the matter, though, was that the Socreds were starting to show their age. Borne out of the desperation of the 1930s and some eccentric (some would say unworkable) theories of monetary reform, Social Credit seemed to come from a bygone era that was very different from the post-oil-boom Alberta it governed. Nevertheless, Manning was greatly respected and his defeat was unthinkable.

Sensing that a generational change might be coming, Peter Lougheed, a lawyer and former Edmonton Eskimos halfback, decided to take on the leadership of the Alberta Progressive Conservatives — a party with no seats in the legislature that managed to run only a half-slate of candidates in 1963. But Lougheed saw it as a better vehicle for his ambitions than the staid old Socreds, and he immediately gave the Tories a youthful, energetic image to match his own.

The Socreds were not completely out of touch, however. Manning approved of attempts to merge Social Credit with the PCs, deputizing two Socreds, including his son Preston, to open negotiations with the PCs, whose own team of negotiators included Joe Clark. They came up with a plan to create an “Alberta Social Conservative Party”, but it went nowhere when old-guard Socreds bristled at the idea of joining the PCs. The Tories, too, decided it wasn’t the best way forward when their prospects seemed bright.

Adopting the slogan “Horizons Unlimited”, Social Credit launched the 1967 Alberta election campaign running on their record of high spending and low taxes. They also aimed their fire at the NDP rather than the PCs, hoping to stir up fears that the spectre of socialism was looming over Alberta.

Lougheed avoided direct attacks on Social Credit, particularly against the much-respected Manning, but he called them ““old and tired — a reactionary administration, reacting day by day”. His party was ready for the campaign, as Lougheed had worked on improving local organizations and identifying quality candidates.

“We’re looking for people who have something unusual going for them,” he said. “They are probably fairly young and probably have never been in politics before, but are well-respected in their communities and are looking for the big challenge.”

The New Democrats under Neil Reimer were running a full slate, and had shown their own organizational abilities when they won a byelection in 1966. Their campaign was centred around the ethics of the Social Credit government. Their lone MLA charged two government members, A.J. Hooke and E. W. Hinman, with abusing their position for personal profit. They would later be cleared by a commission that Manning struck just days before his election call (Hinman, though, would lose the nomination in his own riding over the controversy), but the issue hurt the Socreds’ image as a clean administration.

The Liberals under Michael Maccagno were in worse shape than the other parties, unprepared for the campaign and riven by internal feuds. They joined the NDP in their attack on the Socreds’ ethics, but even a party spokesman admitted it wouldn’t make much of an impact on the electorate because “as far as the public is concerned, Manning could be run over by a bus and they would say it was a smart move”.

The campaign was notable for featuring the province’s first leaders debate. Lougheed challenged Manning to a televised joust, but the incumbent premier ignored him. What the devout evangelical Christian couldn’t ignore was an invitation from the City Centre Church Council to attend a debate at the McDougall United Church in Edmonton.

In front of a crowd of some 1,200, the four leaders answered questions from the audience. Manning performed well, deemed the winner by at least one columnist, but so did Lougheed, who was warmly applauded by the crowd.

“It is fundamental that the government not be considered the be-all and end-all of our democratic process,” Lougheed argued at the debate.

In the end, the biggest issue of the campaign might have been that call for an opposition — any opposition — to Social Credit. It was clear that the PCs were going to do well enough, but the talk was no more lofty than that 10 opposition members might make it to the legislature, up from the five that was estimated at the campaign’s outset. Even Lougheed admitted that winning anything more than seven seats “would be a smashing victory” for the PCs.

As expected, Social Credit was returned with a massive majority. But the party lost five seats and, more worryingly for Manning, 10 percentage points. It took 44.6%, dropping under 50% for only the second time during his tenure.

Lougheed led the PCs to official opposition status, winning six seats and 26% of the vote, a gain of 13 points since the 1963 election. Five of those six seats were won in either Calgary or Edmonton, and all but one of their six MLAs were under the age of 40.

The Liberals retained their three seats but finished with just 10.8% of the vote, a decline that put them behind the shutout New Democrats, who nevertheless increased their vote share by 6.5 points to 16%.

Among the defeated opposition candidates were Joe Clark, future prime minister, in Calgary-South and Grant Notley, future NDP leader and father of Rachel Notley, in Edmonton-Norwood.

The 10th opposition MLA elected was Clarence Copithorne, an Independent who won in Banff-Cochrane.

Shaken by the results, Manning ordered an extensive post-mortem on the campaign to understand what had happened. He wanted his successor to know how to temper “small-c conservative principles with the social conscience of prairie populism”, the recipe that had worked for him so well since he became premier in 1943.

But a generational change in politics was just around the corner. Manning’s successor, Harry Strom, would go down to defeat in 1971 — and usher in the PC dynasty that started with Peter Lougheed.

1971 Alberta Liberal leadership

Third time’s the charm for Bob Russell

March 13, 1971

Since the rise of Social Credit in the 1930s, the Alberta Liberals had been relegated to the political wilderness — lucky to win a seat or two. By 1971, the one glimmer of a potential rebirth was now long behind them. That was the 1955 election when, under the leadership of James Harper Prowse, the Liberals had been able to put a small scare into the Socreds with 31% of the vote and 15 seats.

But their wandering in the wilderness had continued after that, with just two seats in 1963 and three seats in 1967. In that campaign, the party had been reduced to 11% support as Peter Lougheed and the Progressive Conservatives leap-frogged the Liberals to become Social Credit’s chief rival.

Things were falling apart for the Alberta Liberals. Adrian Berry had resigned his leadership in 1966 just months after he had won it, and Michael Maccagno had to step in as interim leader and take the party into the 1967 campaign. He then resigned his provincial seat to run (unsuccessfully) for the Pierre Trudeau Liberals in 1968 and his replacement, John Lowery, was forced to quit in 1970 when Liberals were horrified to hear he had been negotiating an alliance or potential merger with the Socreds.

That meant when the Liberals, seatless since 1969 after their last MLA in the legislature defected to the PCs, gathered to choose their next leader, he would be their sixth in seven years.

Perhaps, after so much disruption, the Liberals were looking for a familiar face. They had one in Robert Russell, a former president of the party and two-time leadership candidate. Still young at 40, the advertising executive from St. Albert had finished a narrow second to Berry in 1966 and a less-narrow third to Lowery in 1969. Would he finally get his shot in his third run at the leadership of a disintegrating party?

The sorry state of affairs the Alberta Liberals found themselves in was reflected by the opponents Russell had to face. Two, Rod Woodcock and John Day, were students in their 20s, while Arthur Yates, 52, had to give up his day job as a foreman at a silver mine in the Northwest Territories to take a run at the leadership.

The three were complete unknowns, making Russell a star candidate by comparison.

Only 324 delegates cast a ballot, but Russell was the overwhelming favourite. He won 69% of the vote on the first ballot, with Woodcock coming a distant second with 16%.

Writing in the Calgary Herald, Don Sellar reported that “most delegates, as well as his three opponents, appeared satisfied with the choice they made at a rather dull, one-day convention”.

It would prove to be a rare victory for Russell. In addition to two past leadership defeats, Russell had also failed to win himself a seat in the 1967 election. He’d fail again in the next provincial election, held in August 1971.

At the convention, he promised delegates he wouldn’t “charge around the province” to name token candidates. He was true to his word, running a slate of just 20 candidates in Alberta’s 65 ridings (Woodcock and Yates among them) in 1971. The Liberals did not elect a single one of them and captured just 1% of the vote. Russell, running in St. Albert, was the top performer with just 15%.

Undaunted, Russell would try to get a seat again in a byelection in 1973. His defeat there finally spelled the end of his provincial political career, though he would twice more try (and fail) to win a seat in the House of Commons in 1984 and 2000.

Being a Liberal in Alberta hasn’t been easy for about a century, but it seems it was especially hard for Bob Russell.

1974 Alberta Liberal leadership

Alberta Liberals choose Taylor

March 2, 1974

Alberta has been a tough place for Liberals for, well, a pretty long time. The Alberta Liberals haven’t won an election there for over a century. And, judging by recent election results in the province, they could be in the wilderness for another century.

But on this day 48 years ago, the Liberals chose a leader they hoped would get them back to the promised land, a leader who would turn out to be the only Alberta Liberal who would take the party into four election campaigns.

The 1971 provincial election was a watershed moment in Alberta, as it ushered in the Progressive Conservatives and ended the decades-long Social Credit dynasty. For the Liberals, though, it was a disaster. The party ran a small slate of candidates and managed just 1% of the vote, failing to win a single seat for the first time in the party’s history.

Bob Russell, the leader, resigned after yet another failed attempt win himself a seat in a byelection, finishing with just 6% of the votes in Calgary-Foothills in 1973.

Despite this, the Liberals were still confident that, with a dynamic new leader, they could replace the spiralling Social Credit Party as the chief opposition to Peter Lougheed’s PCs.

The 1974 Alberta Liberal leadership contest had just two candidates.

There was Calgary-based oil executive Nick Taylor, an outspoken 17-year veteran of party politics. Taylor was a 46-year-old father of nine and someone seen as a bit of a “renegade” within the party.

The other candidate was John Borger, a petroleum and engineering consultant from Edmonton, who also happened to be a former football player for the Calgary Stampeders.

According to the Edmonton Journal, while Taylor served “stomach-warming fuel” at his suite at the convention in Edmonton, Borger “doesn’t drink or smoke. He proudly serves only coffee and cookies at his receptions.”

In addition to style, it was the two candidates’ positions on collaboration with the Liberal Party of Canada that distinguished them. Taylor wanted more separation between the provincial and federal wings, saying that a Robert Stanfield-led PC victory in the upcoming federal election would be helpful, since “then I’m rid of the albatross of having to explain every asinine move Ottawa makes.”

Borger wanted a closer relationship with the two parties with an eye toward electing both provincial and federal Liberals in Alberta. He didn’t want to be a spokesman for Pierre Trudeau in the province, but instead be a “representative from Alberta in the councils of the national party.”

When the votes were counted, Taylor emerged as the victor with 366 votes to 293 for Borger. Another 78 delegates — more than the gap that separated Taylor and Borger — abstained.

Of course, Taylor was taking over a struggling party with no representation in the legislature. Personally wealthy, the party would have to lean on Taylor’s own resources for support.

But he was still realistic, telling reporters after his victory that after the next election he “wouldn’t be unhappy with 70 Tories in the government and five of us on the other side at first.”

Even that modest ambition, though, turned out to be beyond his capabilities. In the 1975 election, the Liberals were again shutout and won only 5% of the vote. That improved slightly to 6% in 1979 and dropped back again to 2% in 1982.

The 1986 election, though, turned out to be the turning point for Taylor and the Liberals. The party won four seats — including Taylor’s riding of Westlock-Sturgeon — and 12% of the vote, placing them as the third party in the legislature behind Don Getty’s governing PCs and Ray Martin’s New Democrats.

Before long, though, Taylor would face a leadership challenge and was replaced by Edmonton mayor Laurence Decore. In 1993, Decore would lead the Liberals the closest to power they have ever been since their 1917 election win, returning the party to the role of the official opposition.

Staying on as an MLA for a few more terms, Taylor would later be named to the Senate by Jean Chrétien. He passed away in 2020. (Dave Cournoyer of Daveberta.ca has a good retrospective here.)

The Alberta Liberal Party that Taylor led for nearly 15 years is now a shadow of its former self, once again shutout of the legislature and coming off an election in which it earned only 1% of ballots cast. It could use another Nick Taylor.

1979 Alberta election

Lougheed scores 74 in ‘79

March 14, 1979

In 1979, Alberta was due for an election, even though its outcome was in little doubt.

Peter Lougheed’s Progressive Conservatives had been in office since 1971, facing little in terms of opposition after winning 69 of 75 seats in the 1975 Alberta election.

In seeking a third term, Lougheed ran on the slogan “Now, more than ever”, asking Albertans to give him a solid mandate to fight the federal government’s designs on Alberta’s oil and gas resources. The campaign was centred around what to do with the billions in revenues filling the Heritage Savings Trust Fund, with Lougheed arguing for prudence to prepare Alberta for the day when oil revenues would dry up.

He warned against the opposition’s reckless spending plans. But whether there should be an opposition at all was perhaps more of an election issue than what the opposition intended to do if it formed government, something no one thought likely.

While publicly hoping for inroads or even an upset, the opposition parties had few realistic chances of defeating the Lougheed PCs. In fact, there were some concerns that Lougheed would sweep all 79 seats on offer.

There were two main opposition parties. Social Credit was still the official opposition, though in its last stages of life. Bob Clark was its leader, after he had finished second to Werner Schmidt in the party’s 1973 leadership race. An MLA since 1960 and a former Socred cabinet minister, this would be Clark’s first campaign as party leader and the party would focus on Calgary and southern Alberta.

For Grant Notley (father of Rachel), this would be his third election as leader of the NDP. Running under the slogan “Send them a message”, Notley was hoping to emerge from the campaign as no longer the party’s sole MLA, which he had been since 1971. His party’s best chances were in the north and in Edmonton.

The Liberals had some limited expectations of a breakthrough after they made some small gains under Nick Taylor in the 1975 election. The Liberals would run a full slate and wage a provincewide campaign, but would not be a major factor, ending with just 6% of the vote and zero seats (again).

As expected, the PCs with their fully-funded war chest won a big victory. The party captured 74 seats, a gain of five from 1975 (four seats had been added to the map). Lougheed’s share of the vote dropped five points to 57%, but the PCs were able to sweep both Calgary and Edmonton again. The party also experienced a bit of rejuvenation, as nearly half of the outgoing caucus didn’t run for re-election.

Social Credit retained its official opposition status, winning the same four seats it had at dissolution: three rural seats in the south and a suburban seat near Edmonton. Its share of the vote increased two points to 20%, what would out to be a last hurrah for Social Credit.

Notley would return to the legislature as its only New Democrat, winning his seat in the northwest of the province. The party’s vote share increased three points to 16% and the NDP finished second in nearly all of Edmonton’s ridings. But it couldn’t finish first in any of them. “I’m too old to cry,” said Notley, “but it hurts too much to laugh.”

The 1979 election would be the last in which Social Credit, that colossus that governed Alberta from 1935 to 1971, would play a major role. It would fall apart before the next election, failing to run a full slate and falling short of even 1% of ballots cast.

Lougheed would stick around to fight the Pierre Trudeau Liberals (along with his minuscule domestic opposition) for a few more years, leading the Progressive Conservatives to an even bigger majority victory in 1982, his last election as leader. That campaign would also prove to be Notley’s last, as he led the NDP past the flailing Social Credit to finally form the official opposition — with two seats.

1982 Alberta election

Lougheed’s last dominating victory

November 2, 1982

By 1982, the province of Alberta was already deep into its fourth political dynasty. The Progressive Conservatives had been in power since 1971, the turning point election that saw Social Credit’s long 36-year run in power come to an end.

In the decade that followed his victory, Lougheed coupled Alberta’s booming economic growth due to the expansion of the oil and gas industry with fights with the federal government led by Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals to produce huge majority wins. Under Lougheed, the PCs captured 69 of 75 seats in the 1975 election and 74 of 79 seats in 1979.

In the years running up to the 1982 election, Lougheed took part in the negotiations to repatriate Canada’s constitution and went to war against the federal government’s National Energy Program, which tried to centralize control over the country’s energy industry and oil prices — and cost Alberta billions in revenues.

The economy was starting to slow in the early 1980s and the NEP was despised in the province. Disputes with the government in Ottawa gave rise to separatism in Alberta and the emergence of the Western Canada Concept. This party shook Alberta politics when it scored a victory in a February 1982 byelection in the rural riding of Olds-Didsbury. Gordon Kesler, the WCC candidate, took away a seat that had previously been held by Social Credit.

When Lougheed launched the election in 1982, well ahead of the end of his term in office, he took aim at Kesler and the WCC, arguing that voting for a separatist party to stick it to Ottawa would only lead to disruption and chaos in Alberta.

But he still had a delicate balancing act to perform — he couldn’t go after the federal government as he might have in the past and risk pushing votes to the WCC.

Instead, the campaign largely focused on provincial issues. The PCs waged a relatively low-key campaign, with Lougheed turning down debates with opposition leaders and PC candidates keeping away from all-party forums. Even big rallies were shelved in order to avoid them being disrupted by small, but vocal, anti-government protesters.

Still, Lougheed faced little real opposition. Only two other parties ran a full (or nearly full) slate of candidates: the Western Canada Concept, and the New Democrats under Grant Notley (father of Rachel Notley, the current Alberta NDP leader).

Notley was the NDP’s only MLA at dissolution, but despite leading the party to just that single seat in the 1979 election Notley was nevertheless taking the NDP into its fourth election with him as leader.

The Liberals, under Nicholas Taylor since 1974, had been struggling for years under the shadow of the unpopular Trudeau government and didn’t run a candidate in a majority of ridings. Neither did the once mighty Social Credit, which was riven by internal feuding and on its way to oblivion.

But with 74 of 79 seats in the previous election, it seemed that the PCs had nowhere to go but down. The controversies and scandals that had piled up after 11 years in office had taken a bit of a toll and the party was expecting some losses. Unnamed observers cited by The Globe and Mail posited that the opposition parties might even be able to win as many as 18 to 25 seats, if the NDP made inroads in Edmonton and the WCC picked up enough of the Socred vote in southern Alberta.

Instead, in an election that featured considerably higher turnout than in 1979, the PCs won the biggest election victory they would ever win. The PCs picked up one seat, finishing with 75, and 62.3% of the province wide vote. That was up nearly five percentage points from three years earlier.

The PCs made two seat gains — they lost a seat to Ray Martin of the NDP in Edmonton — and one of those gains was Olds-Didsbury, the seat where Gordon Kesler and the WCC had made their byelection breakthrough.

While the NDP’s two seats and 18.8% of the vote might not have met the lofty expectations of some, it was still enough for Notley to become the leader of the opposition. The last time the party had accomplished that was under the old CCF banner.

Social Credit was wiped off the map, taking less than 1% of the vote. Two former Socred MLAs, Walter Buck and Raymond Speaker, decided to run as Independents and were successfully re-elected.

The Western Canada Concept was shut out of the seat count, but the party still captured 12% of the vote. This remains the best performance by any Western separatist party.

The Liberals were also shut out, but Taylor was philosophical on election night, recognizing the PC advantage and that “none of the kings and sheiks of the Middle East have been thrown out of power and as long as you have nature’s goodies to give out, you look pretty good to the electorate.”

While the pinnacle of their electoral careers, the 1982 election would be the last campaigns for both Lougheed and Notley. In 1984, still only 45 years old, Notley died in a plane crash near Slave Lake. Ray Martin, the party’s only other MLA, took over and led the NDP to a breakthrough and 16 seats in 1986.

Lougheed had stepped away by then. After the 1982 election, the Alberta premier would stay on for three more years until resigning in 1985 and being replaced by Don Getty. With more than 14 years in the job, Lougheed remains second on the list of longest-serving Alberta premiers — after Ernest Manning, the master of the political dynasty Lougheed’s PCs had put to an end.

NOTE ON SOURCES: When available, election results are sourced from Elections Alberta and J.P. Kirby’s election-atlas.ca. Historical newspapers are also an important source, and I’ve attempted to cite the newspapers quoted from.

In addition, information in these capsules are sourced from the following works:

Alexander Cameron Rutherford: A Gentleman of Strathcona, by D.R. Babcock

Alberta Premiers of the Twentieth Century, edited by Bradford J. Rennie

John E. Brownlee: A Biography, by Franklin Foster

The Good Steward: The Ernest C. Manning Story, by Brian Brennan